|

|

1 CD -

8-557526 - (c) 2008

|

|

1 CD -

3-7475-2 - (p) 2001 */**

|

|

| THE ROBERT

CRAFT COLLECTION - The Music of Arnold

Schoenberg - Volume 8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arnold

SCHOENBERG (1874-1951) |

Chamber

Symphony No. 2, Op. 38 (1939)

|

*

|

|

18' 46"

|

|

|

-

Adagio

|

|

7' 23" |

|

1 |

|

-

Con fuoco

|

|

11' 23" |

|

2 |

|

Die

glückliche Hand, Op. 18 (1913)

|

** |

|

21' 14" |

|

|

-

I. Bild

|

|

3' 23" |

|

3 |

|

-

II. Bild |

|

5' 11" |

|

4 |

|

-

III. Bild

|

|

6' 57" |

|

5 |

|

-

IV. Bild

|

|

5' 43" |

|

6 |

|

Wind

Quintet, Op. 26 (1924) |

*** |

|

38' 21" |

|

|

-

Schwungvoll

|

|

12' 00" |

|

7 |

|

-

Anmutig und heiter; Scherzando

|

|

9' 10" |

|

8 |

|

-

Etwas langsam. Poco adagio

|

|

8' 45" |

|

9 |

|

-

Rondo

|

|

8' 26" |

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

Mark

Beesley, Bass **

|

SIMON JOLY

CHORALE **

NEW YORK WOODWIND QUINTET

***

PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA */**

Robert

CRAFT, conductor |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Abbey

Road Studio One, London (England):

- 26 May 2000 (Op. 38)

- 27/28 July 2000 (Op. 18)

American Academy of Arts and

Letters (USA) - 6 to 8 January

2004 (Op. 26)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Gregory K.

Squires

|

|

|

Balance

Engineer

|

|

Michael

Sheedy (Opp.

38, 18) |

|

|

Engineer |

|

Andrew

Dudman, Graham Kirkby, Mirek

Stiles (Opp. 38, 18)

Gregory K. Squires (Op. 26)

|

|

|

Production

assistance

|

|

Fred

Sherry

|

|

|

Digital editing |

|

Wayne

Hileman

|

|

|

NAXOS Edition |

|

Naxos

- 8.557526 | (1 CD) | LC 05537 |

durata 78' 21" | (c) 2008 | DDD

|

|

|

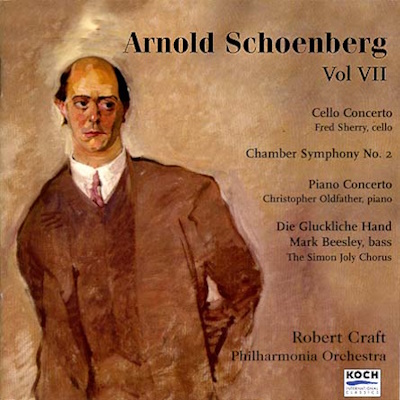

KOCH previously

released |

|

KOCH

International Classics | 3-7475-2

| (1 Cd) | LC 06644 | (p) 2001 |

DDD | (Opp. 38, 18)

|

|

|

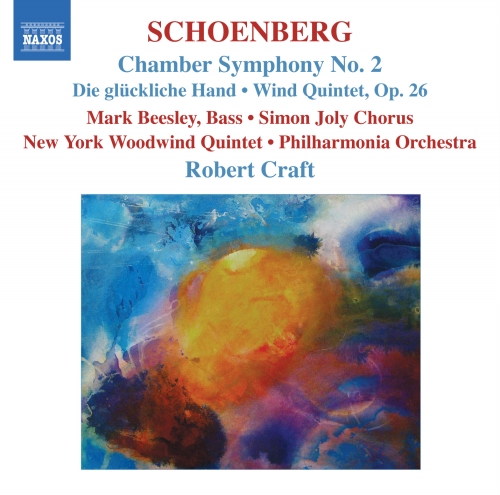

Cover |

|

Sun

by Ultich Osterloh (courtesy

of the artist)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The little-known Second

Chamber Symphony ought to be

the most popular of Schoenberg’s

later masterpieces. Neither

“atonal” nor “twelve-tone”, it

contrasts a lush, melodious,

dramatic first movement with a

rapid and richly polyphonic second

movement. Die glückliche Hand

is a pantomime for two silent

actors and one solo singer, “the

Man”. The music is very

compressed, and its two middle

scenes, apart from the lines by

the Man, are purely orchestral.

Realising that a work of 38

minutes in atonal idiom for five

winds might be less

audience-friendly than any of his

music heretofore, Schoenberg

imparted his Wind Quintet

with a display of instrumental

virtuosity that surpassed anything

even he had ever attempted.

Chamber Symphony No. 2 In two

movements: Adagio and Con fuoco

The Second Chamber Symphony

was begun in August 1906, soon

after the completion of the First

Chamber Symphony, but set

aside until the summer of 1939,

when Schoenberg returned to the

piece, finishing the first

movement on 14th August and the

second on 21st October, 1939. A

letter from the composer to Fritz

Stiedry, who conducted the

première in a broadcast concert in

Town Hall, New York, 15th

December, 1940, reveals the

history of the opus:

[Between 1906 and

1939] my style has become much

more profound and I have much

difficulty in making the ideas

which I wrote down many years

ago without too much thought

(rightly trusting to my

feeling for design) conform to

my present demand for a high

degree of “visible” logic.

This is now one of my greatest

difficulties, for it also

affects the material of the

piece.

… This

material is very good:

expressive, characteristic,

rich, and interesting. But it

is meant to be carried out in

the manner which I was capable

of at the time of the Second

Quartet.

The first movement is

finished. I have altered very

little; only the ending is

entirely new, and the

instrumentation. In a few

places I have altered the

harmonization, and I have

changed the accompaniment

figures rather frequently.

After numerous experiments, I

decided to rework these

completely. I am very well

satisfied with the movement.

Besides, it is easy to play;

very easy …

Now I am working on the second

movement. If I succeed in

finishing it, it will be quite

effective: a very lively

Allegro … The last movement

[eventually the end of the

second movement] is an

“epilogue”, which does bring

thematically new material… The

musical and “psychic” problems

are presented exhaustively in

the two completed movements;

the final movement merely

appends, so to speak, certain

“observations”.

Schoenberg

wrote to Stiedry again after

hearing acetate recordings of his

première performance of the piece:

I find the strings too

noisy, and this is because

each of the staccatos marked

is played sforzato instead of

being played as an unusually

short note. For me, the noise

of the strings is so

distorting that the winds do

not come out plastically

enough. [Apropos] the detached

notes, [they] were mostly

played as staccatos. This is

wrong—at least in my music. I

really mean that each note

should be bowed — or breathed

— separately (8th January,

1941).

The

little-known Second Chamber

Symphony ought to be the

most popular of Schoenberg’s later

masterpieces. Neither “atonal” nor

“twelve-tone”, it contrasts a

lush, melodious, dramatic first

movement with a rapid and richly

polyphonic second movement. The

first movement has always been

popular, but the far more

difficult-to-play second movement

is still (2008) underappreciated.

The Allegro movement invites

comparison with the middle

movement of Stravinsky’s Ode, if

only in rhythm, the exploitation

of a six-eightmetre accommodating

twos and threes simultaneously,

the syncopations and offbeats. But

the Schoenberg is incomparably

more abundant in substance,

emotional power, and compositional

skill, the Stravinsky being

rigidly diatonic, homophonic, and

mired in protracted temporizing.

The Schoenberg further requires a

much higher degree of instrumental

virtuosity than any piece by

Stravinsky. The music of both

composers in this period is still

labeled as “neoclassic”. If the

reader has a score, he or she

should turn to bar 453 of

Schoenberg’s Con fuoco, and enjoy

the thrilling timbre of the

bassoon doubling of the clarinet.

Die glückliche Hand

Schoenberg wrote the Die

glückliche Hand libretto

(“The Hand of Fate” would be a

better title), a “Drama With

Music”, in June 1910, and began

the music three months later, on

9th September. Composed in early

1912, before Pierrot Lunaire,

the music was completed after it,

in 1913. The full score

manuscript, in the Library of

Congress, is dated “November 18,

1913, Berlin”. The first and last

scenes were written last,

Schoenberg having changed his mind

about the form of the opus while

he was working on the transition

to the final scene, the jagged

music near the end of the third

scene that accompanies the Man’s

pursuit of “the beautiful woman”

through a rocky landscape, a scene

that concludes when she dislodges

a boulder from a place above him

that falls on and crushes him. The

1910 libretto makes no mention of

the off-stage band and the mocking

laughter from the chorus that

distinguish the first and last

scenes and that are the same in

both as well as in their

bass-clarinet and bassoons

ostinato introductions.

Soon after completing Die

glückliche Hand, Schoenberg

began to generate ideas about its

realization on stage. He wanted

“the greatest unreality,” a “play

with apparitions of colours and

forms, designed by Kandinsky or

Kokoschka”. In the spring of 1914

the composer met with the

Intendant of the Dresden Opera,

Count Seebach, to discuss the

possibility of staging the work,

together with Erwartung,

but World War I forced the delay

of a première for a decade, Erwartung

in Prague and Die glückliche Hand

in Vienna, by which time new

developments had alienated the

aesthetics and the musico-dramatic

languages of both.

Die glückliche Hand is a

pantomime for two silent actors

and one solo singer, “the

Man”—whose nine brief sung phrases

are hardly comparable to the long,

overpowering vocal rôle of “the

Woman” in Erwartung. (Apart from

its division into four scenes, Die

glückliche Hand contains no

significant resemblances to

Erwartung.) The Glückliche Hand

music is very much more compressed

than that of Erwartung, and its

two middle scenes, apart from the

lines by the Man, are purely

orchestral. The first and fourth

scenes employ a small chorus of

six female and six male singers

and an offstage band of seven

players, whose music is

superimposed on the large

orchestra. Further, Die glückliche

Hand returns to traditional

elements, a symmetrical form,

clear divisions (somewhat in the

sense of a “number” opera),

motivic development, repetition

(the three-note, minor-second

down, majorsecond- up motive,

introduced by the flute in bar 126

and after that successively

throughout the orchestra more

times than any other motive in

Schoenberg’s music, and a greatly

expanded use of ostinato. For this

last, the entire first scene is

constructed on a double ostinato,

one of the two components played

by timpani and harp in the bass

register, the other by solo violas

and cellos in the upper register.

This nine-note “ostinato chord”,

as Schoenberg referred to it,

quietly accompanies the twelve

singers, who whisper, sing, and

speak-sing (Sprechstimme)

in elaborate polyphony. The third

scene begins with an ostinato, and

more of them are found at bars

97–100, 129–130, 140–142, 146–153,

181–184 (“choo-choo” train music

reminiscent of the ostinato

scene-changing music in

Erwartung.) The twelve vocal parts

at the end of Scene Four are

almost entirely sung (no Sprechstimme)

and they are stronger and more

prominent than in Scene One.

Apart from the chorus and the nine

short phrases sung by the Man, the

libretto is in the stage

directions (see below). The “plot”

is simple. At the beginning, we

see the Man lying face down, head

toward the audience, feet toward

the inner stage. A monster (hyena

species with bat wings) gnaws at

his neck. The chorus is positioned

behind a dark curtain at the rear

centre stage, their twelve

green-lit faces peering through

holes in the curtain. The Man is

the Great Artist (Schoenberg) and

the gnawing monster is his ego,

which craves recognition and

acclaim. The “Greek” chorus

upbraids the Man for desiring the

futile rewards of success: “You

poor fool … You, who have the

divine in you, yet covet the

worldly.” At the start of Scene

Two a beautiful woman appears. She

gives a goblet to the Man, who

drinks its contents but does not

see her, whereupon the woman loses

her initial sympathy for him and

goes to the side of the stage

where an “elegantly dressed

gentleman” takes the woman in his

arms. They go off together, and

the Man groans, but in a moment

the Woman returns to him. At the

end of the scene she leaves him

again. This, of course, is

autobiography. In 1908,

Schoenberg’s wife, Mathilde,

eloped with a young painter,

Richard Gerstl, who had been

working on Schoenberg’s portrait.

Not long after the elopement

Gerstl hanged himself. Anton

Webern, Schoenberg’s pupil,

persuaded him to take her back.

The composer’s public humiliation

at the time, not to mention his

anger and wounded pride, are

revealed in a letter to Alma

Mahler, 7th October, 1910:

If I am to be honest

and say something about my

works (which I do not

willingly do, since I actually

write them in order to conceal

myself thoroughly behind them,

so that I will not be seen),

it could only be this: It is

not meant symbolically, but

only envisioned and felt. Not

thought at all. Colour,

noises, lights, sounds,

movements, looks, gestures —

in short, the media which make

up the ingredients of the

stage — are to be linked to

one another in a varied way.

Nothing more than that. It

meant something to my emotions

as I wrote it down … I don’t

want to be understood: I want

to express myself — but I hope

that I will be misunderstood.

Scene Three begins with a

unison figure in bass octaves

(lower strings, harp, bass

clarinet, bassoons) with the

character of a fugue subject.

The second entrance repeats

the rhythm of the subject but

not the notes. The Man goes to

a cave where he discovers a

goldsmith’s shop with several

workers. In the middle is an

anvil, a huge hammer under it.

As the Man contemplates the

workers, he remarks that what

they are doing can be done

more simply. He goes to the

anvil, places a block of gold

on it, then brings the hammer

down on it, splitting the

anvil and allowing the gold to

fall into the cleft. The

workers had been preparing to

stop him, but when he

retrieves a perfect diadem set

with precious stones they

express wonder at the

achievement. (The glitter of

the jewel is evoked by a

mixture of trills and

flutter-tonguing in the wind

instruments.) Eventually,

after he gives his masterpiece

to them, they decide to attack

him, at which point the scene

changes. The woman returns,

now naked to the hip on her

left side, and the “elegant

gentleman” returns as well. He

follows the woman, who climbs

to the top of a plateau. The

Man pursues her through rocky

terrain. The woman attains a

higher elevation and dislodges

a boulder toward the Man, who

is standing below, hitting and

burying him. The Fourth Scene

returns to the first, with, at

the end, the chorus mocking

the Man: “Must you live again

what you have so often lived?

You poor fool!”

Apart from

the aforementioned personal

history, the allegory symbolizes

the successful Viennese composer

of operettas and popular music in

the “elegantly dressed gentleman,”

while the incompetent workmen are

untalented, hack composers, and

the anvil that the Man crushes —

the blow of a huge wooden hammer

is heard in the orchestra at this

point (bar 115) — can be thought

of as representing tonality, the

diadem, one of the beautiful

objects that the man of genius

will create, symbolizes the new

atonality. (In addition to the

hammer, the orchestral arsenal

includes a “Metallrohr”,

an instrument known to the

fabricators of “Musique

Concrète”.)

At the time of composing Die

glückliche Hand, Schoenberg

was an exhibiting painter,

personally and artistically close

to Kandinsky, which explains the

composer’s addition of a colour

dimension to this Gesamtkunstwerk

dream-world opera. The colour

changes are “notated” in the score

by some seventy abstract signs

indicating the varying shades and

intensities of coloured lights

shifting in correspondence to the

stage action. This colour

sign-language requires exact

synchronization between the aural

and the visual components. The

principal event in Scene Three is

“a crescendo of colour”: red,

brown, dirty green, blue-gray,

violet, timed to the music of bars

125–139. As Schoenberg wrote, “The

play of lights and colours is

based not only on intensities, but

on values which can only be

compared with pitches.”

Wind Quintet, Op. 26

The neo-classicism of Schoenberg’s

music from about 1920 is wholly

different from what might have

been predicted from his principal

composition (unfinished) during

World War I, Jacob’s Ladder.

This new direction developed

simultaneously with the invention

of a new compositional technique

variously known as dodecaphonic

and serial. Classical forms

provided the structural frames for

the atonal music of Op. 23, Op.

24, Op. 25, and Op. 26, though

serial procedures are introduced

in only one movement of Opus 23

and Opus 24. The two later

compositions are entirely

“dodecaphonic”. But, then, every

Schoenberg opus is complete in

itself and its stepping-stone

foundation component should be

disregarded. The composer’s

commitment to the polyphonic art

of Bach began with the Quintet,

the Four Choruses, Op. 37,

and the Satires, Op. 28.

When I wrote to him in June 1950

comparing Opus 28 to the Musical

Offering, he quickly

answered: “You place me too high”,

but he was clearly aware of the

correspondence between the two

works.

Whereas the movements of the

Serenade, Op. 24, and the Piano

Suite, Op. 25, are modeled

on late- Baroque dance forms

(Minuet, Gigue, Gavotte), the

Quintet follows the structure of

the four-movement sonata form,

with a repeated exposition in the

first movement and a Rondo finale.

The scope of the piece is

symphonic, and the texture recalls

the contrapuntal style of the First

Chamber Symphony.

Realising that a work of 38

minutes in atonal idiom for five

winds might be less

audience-friendly than any of his

music heretofore, Schoenberg

sought to beguile his masterpiece

with a display of instrumental

virtuosity that surpassed anything

even he had ever attempted. Only

now, a half-century after the

première, has the piece become

playable at the tempos Schoenberg

requires. The wind-instrument

players of his time had to be

conducted (Webern rehearsed and

conducted it in the early years)

and managed to get through it in

about an hour. Composed between

21st April, 1923 and 26th July,

1924, the first performance, by

members of the Vienna

Philharmonic, took place in that

city, conducted by Schoenberg’s

son-in-law Felix Greissle, on 13th

September, 1924, Schoenberg’s

fiftieth birthday. It lasted one

hour. The present recorded

performance takes 38 minutes.

Robert Craft

|

|