|

|

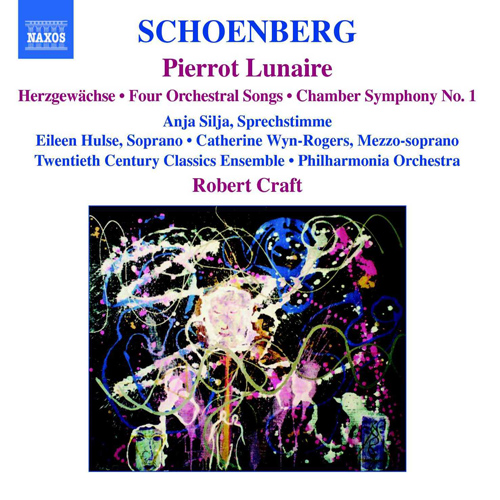

1 CD -

8-557523 - (c) 2007

|

|

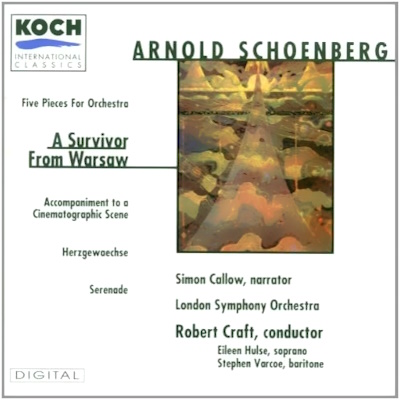

1 CD -

3-7263-2 - (p) 1995 *

|

|

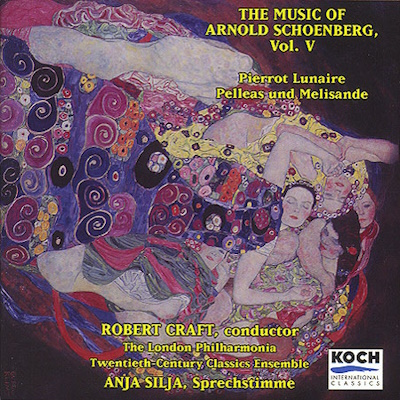

1 CD -

3-7471-2 - (p) 2000 **

|

|

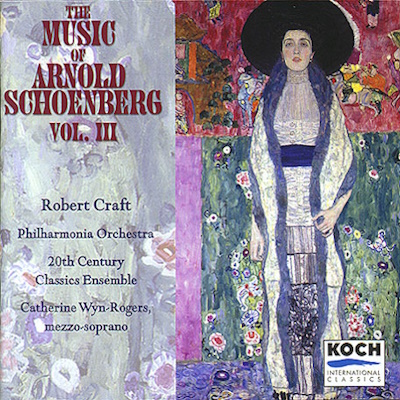

1 CD -

3-7463-2 - (p) 1999 ***/****

|

|

| THE ROBERT

CRAFT COLLECTION - The Music of Arnold

Schoenberg - Volume 6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arnold

SCHOENBERG (1874-1951) |

Herzgewächse,

Op. 20 (1911) for coloratura

soprano, celesta, harmonium and harp

|

*

|

|

3' 31"

|

1 |

|

Pierrot

Lunaire, Op. 21 (1912)

|

** |

|

36' 30" |

|

|

Part One

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Moondrunck

|

|

1' 54" |

|

2 |

|

-

Columbine

|

|

1' 43" |

|

3 |

|

-

The Dandy

|

|

1' 27" |

|

4 |

|

-

An ethereal Washerwoman

|

|

1' 29" |

|

5 |

|

-

Chopin Waltz

|

|

1' 23" |

|

6 |

|

-

Madonna

|

|

2' 05" |

|

7 |

|

-

The Sick Moon

|

|

3' 06" |

|

8 |

|

Part Two |

|

|

|

|

|

-

Night

|

|

2' 27" |

|

9 |

|

-

Prayer to Pierrot

|

|

1' 06" |

|

10 |

|

-

Theft |

|

1' 13" |

|

11 |

|

-

Red Mass

|

|

1' 52" |

|

12 |

|

-

Gallows Song

|

|

0' 18" |

|

13 |

|

-

Beheading |

|

2' 19" |

|

14 |

|

-

The Crosses

|

|

2' 20" |

|

15 |

|

Part Three |

|

|

|

|

|

-

Homesickness |

|

2' 17" |

|

16 |

|

-

Vulgarity |

|

1' 13" |

|

17 |

|

-

Parody |

|

1' 25" |

|

18 |

|

-

The Moonspot

|

|

0' 54" |

|

19 |

|

-

Serenade |

|

2' 30" |

|

20 |

|

-

Homeward Bound

|

|

1' 53" |

|

21 |

|

-

O Ancient Fragrance

|

|

1' 36" |

|

22 |

|

Four

Orchestral Songs, Op. 22 (1916) |

*** |

|

13' 32" |

|

|

-

Seraphita

|

|

5' 25" |

|

23 |

|

-

Alle, welche dich Suchen

|

|

1' 59" |

|

24 |

|

-

Mach mich zum Wächter deiner

Weiten

|

|

3' 49" |

|

25 |

|

-

Vorgefühle

|

|

2' 19" |

|

26 |

|

Chamber

Symphony No. 1, Op. 9 (1906) -

Original Version

|

**** |

|

20' 20" |

27 |

|

|

|

|

Hergewächse, Op.

20 *

Eileen Hulse,

Soprano

Members of the

LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

- John Alley, Harmonium

- Tim Carey, Celeste

- Sioned Williams, Harp

Robert CRAFT, conductor

|

Pierrot Lunaire,

Op. 21 **

TWENTIETH

CENTURY CLASSICS ENSEMBLE

- Anja Silja, Sprechstimme

- Christopher Oldfather, Piano

- Michael Parloff, Flute/Piccolo

- Charles Neidich, Clarinet/Bass

clarinet

- Rolf Schulte, Violin/Viola

- Fred Sherry, Cello

Robert

CRAFT, conductor |

Four Orchestral

Songs, Op. 22 ***

Catherine

Wyn-Rogers, Mezzo-soprano

PHILHARMONIA ORCHESTRA

Robert

CRAFT, conductor

|

Chamber Symphony

No. 1, Op. 9 ****

TWENTIETH

CENTURY CLASSICS ENSEMBLE

- Tara Helen O'Connor, Flute/Piccolo

- Stephen Taylor, Oboe

- Melanie Feld, English horn

- Charles Neidich, E-flat

Clarinet

- Alan Kay, Clarinet

- Michael Lowenstern, Bass

clarinet

- Frank Morelli, Bassoon

- Harry Searing, Contra-bassoon

- William Purvis, French horn

- Christopher Komer, French

horn

- Rolf Schulte, Violin

- Camit Zori, Violin

- Toby Appel, Viola

- Fred Sherry, Cello

- Donald Palma, Double bass

Robert

CRAFT, conductor |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Abbey

Road Studio One, London (England)

- 28 and 29 May 1994 (Op. 20)

American Academy of Arts and

Letters (USA) - 1997 (Op. 21)

Abbey

Road Studios, London (England) -

July and October 1998 (Op. 22)

Recital Hall, Performing Arts

Center, SUNY Purchase, Purchase,

New York (USA) - 16 September

1998 (Op. 9)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Michael

Fine (Op. 20)

Gregory

Squires (Opp. 21, 22, 9)

|

|

|

Engineer |

|

Simon

Rhodes (Op. 20)

Richard Squires (Op. 21)

Michael Sheedy (Op.

22)

Gregory Squires (Op. 9)

|

|

|

Assistant

engineers

|

|

Alex

Scannell (Op. 22)

Dave Forty (Op. 22)

|

|

|

Editor |

|

Michael

Sheadyy (Op. 22)

Richard Price (Op. 9)

|

|

|

NAXOS Edition |

|

Naxos

- 8.557523 | (1 CD) | LC 05537 |

durata 73' 53" | (c) 2007 | DDD

|

|

|

KOCH previously

released |

|

KOCH

International Classics | 3-7263-2

| (1 Cd) | LC 06644 | (p) 1995 |

DDD | (Op. 20)

KOCH

International Classics |

3-7471-2 | (1 Cd) | LC 06644 |

(p) 2000 | DDD | (Op. 21)

KOCH

International Classics |

3-7463-2 | (1 Cd) | LC 06644 |

(p) 1999 | DDD | (Opp. 22, 9)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Zimzum

by Ultich Osterloh (courtesy of

the artist)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Arnold Schoenberg

sought to write music that avoided

traditional tonal implications,

which eventually led him away from

tonality altogether. Herzgewächse

is a short piece for high soprano

and what has been called ‘an

awkward ensemble’. It is an

example of the ‘sound of colour’,

the result of Schoenberg’s

collaboration with his friend, the

avant-garde painter Kandinsky. One

of Schoenberg’s best-known works,

Pierrot Lunaire marks a

return to counterpoint. His Four

Orchestral Songs balance the

traditional settings of texts with

innovatory instrumentation, while

the propulsive power of the

earlier Chamber Symphony

brings to mind the music of

Beethoven.

Herzgewächse, Op. 20 (1911),

for coloratura soprano, celesta,

harmonium and harp

Completed on 9 December 1911, Herzgewächse

was not performed until April

1928, when Marianne Rau-Hoeglauer

sang it in Vienna under Anton

Webern's direction. The harmonium,

the first instrument to sound,

plays more continuously than the

other two, having less than a

single full beat of rest as

against a total of six silent bars

in the celesta and four in the

harp. The stops employed are

flute, oboe, English horn,

clarinet, bass-clarinet, bassoon,

muted trombone, violin, viola,

cello, and percussion

(unspecified). They alternate

according to the phrasing of the

music. Curiously, no timbres are

indicated in the nine next-to-last

bars.

After a brief instrumental

introduction and the first couplet

of the vocal part, the music is

harmonically dense: chords of

nine, ten, and eleven pitches

occur frequently. Schoenberg's

setting of the text parallels the

sense of the words; thus at " sink

to rest " the pitches descend,

quietly and without accompaniment,

to the lowest vocal note of the

piece, and those for "imperceptibly

ascending" climb slowly and

softly from a low note to C in alt.

The vocal range is that of the

Queen of Night in The Magic

Flute and of Blonde in Abduction

from the Seraglio.

Pierrot Lunaire

Schoenberg chose the 21 poems of

his Pierrot Lunaire from

the cycle of fifty by the Belgian

poet Albert Giraud (Albert

Kayenbergh, 1860-1929), published

in 1884. The verse form is the

same for all but one of them. They

are rondeaux of thirteen lines, in

which lines seven and eight repeat

lines one and two. (Number

thirteen, the exception, repeats

line one only.) Schoenberg used

the 1911 edition of the German

translation made by Otto Erich

Hartleben in the 1890s, which is

more vivid in language and

stronger in feeling than the

French original. Hartleben also

changes the tense from past to

present, substitutes more

colourful images of his own, and

transforms a flat, even recitation

in octosyllabic lines into an

agitated, exclamatory, fragmentary

style in a variety of metres with

considerable use of enjambement.

In Hartleben, the moon is a

washerwoman, and not, as in

Giraud, "comme une lavandière".

Schoenberg chose poems with

related subject-matter and grouped

them into three cycles of seven

poems each. The subjects of the

first are the poet's ecstasy - the

moon is the symbol of poetry - and

artistic rebellion; of the second,

his frustration, weakness, and

despair; and of the third his

reconciliation with the past and

tradition, and the return from

Venice to his native Bergamo. The

form of recitation is the Melodramen,

in which the words are spoken with

musical accompaniment. This genre

seems to have originated with J.

J. Rousseau's Pygmalion

(1762), but the best-known

examples are by Mozart and

Schubert. In Schoenberg's case,

the recitation, called Sprechstimme,

is a combination of speech and

song notated in exact pitches and

rhythms. Despite the composer's

insistence that the part should

not be sung, clearly the pitch

functions of the recitation are

essential to the melodic-harmonic

conception of the piece. In a few

places the Sprechstimme is

required to sing normally, but for

only a very few notes.

Pierrot's most distant ancestor is

the Commedia dell'Arte

Pulcinella, but in France the

farcical Neapolitan impostor and

prankster became the harlequin,

the prototype of the melancholy

artist. Watteau called him Gilles;

Théophile Gautier's play, Pierrot

Posthumous, marries him to

Columbine; Verlaine transforms him

into a madman, blasphemous, and

the "personification of the

death-obsessed soul"; Théodore de

Banville, publishing in the same

year as Giraud, praises Pierrot's

"joie", and Jules Laforgue

introduces irony as a principal

ingredient. Giraud's inspiration

was the poetry of Les Fleurs

du mal.

Part I establishes that the time

is night, that Pierrot, a poet and

dandy from Bergamo, is

"moondrunk," and intends to

present his beloved Columbine with

blossoms of moonlight. He daubs

his face with moonlight, and the

moon washes clothes made of

moonbeams. A "Valse de Chopin"

evokes a drop of blood on the lips

of a consumptive. Pierrot presents

his verses to the Madonna "of all

sorrows", and the poet is

crucified on his verses. The moon

is pale with lovesickness.

The images of Part II are morbid

and violent. Night descends when

the wings of a giant moth eclipse

the sun. Pierrot becomes a

blasphemer and a grave-robber

whose life will end on the

gallows, though between-times he

sees the moon as a scimitar that

will decapitate him.

The theme of Part III is

homesickness, the nostalgia for

the "Italian Pantomime of old",

and eventual homecoming to Bergamo

from, it seems, Venice, since the

penultimate piece is a barcarolle,

and since a moonbeam is the rudder

of Pierrot's water-lily

conveyance. Enacting bygone

grotesqueries and rogueries, he

drills a pipe bowl through the

gleaming skull of Cassander, fills

it with Turkish tobacco, inserts a

cherry pipe stem in the polished

surface, and puffs away. He

interrupts his midnight serenade

(cello) to scrape the instrument's

bow across Cassander's bald pate.

Then, discovering a white spot on

the collar of his black jacket, he

tries to rub it out, thinking it a

fleck of plaster, only to

discover, in the light of dawn,

that it was the moon. In the final

piece, the poet invoking the

fragrance of a world long past,

attains peace.

The musical content of Part I is

comparatively simple. That of Part

II is increasingly complex, while

Part III, the most intricate of

all, ends tranquilly. Eight

instruments are required, but only

five players, since the violinist

also plays the viola, the flautist

the piccolo, the clarinettist the

bass clarinet. Piano and cello

complete the ensemble. All eight

instruments are used only in the

last piece. Schoenberg's intent

was to draw new sounds from

traditional instruments, not to

experiment with new instruments,

as Stravinsky did with percussion

in Histoire du Soldat.

Four Orchestral Songs, Op. 22

In a 1932 Frankfurt broadcast talk

on the Four Songs,

Schoenberg stated that "my feeling

for form, modeled on the great

masters, and my musical logic …

must guarantee that what I write

is formally and logically correct,

even if I do not realise it.… [The

third and fourth songs] do not

dispense with logic, but I cannot

prove it." He goes on to say that

he hears relationships in the work

that he is unable to discern

through the eye, and that "Only in

this way is it possible to

perceive the similarity between

the first bar of the orchestral

introduction [to No. 3] and the

first bar of the voice part."

Then, turning to the question of

form - shapes and proportions - he

concedes that "compositions for

texts are inclined to allow the

poem to determine their form, at

least outwardly," and he

identifies the "outward" as the

correspondence of "declamation,

tempo, and dynamics."

It seems characteristic of

Schoenberg that his most original

and lapidary orchestration is

found in a vocal work, one in

which, moreover, he had composed

the singer's part in the first and

the fourth songs even before

beginning to sketch the orchestral

accompaniment. Further, in that

balance of tradition and

innovation which is the foundation

of his musical philosophy, the

traditional element in the Songs,

Op. 22, is in the setting of the

texts. Thus he generally follows

Brahms in duplicating the accent

patterns of the verses in the

music, even though the "logic" in

Brahms's songs, as distinguished

from the inexplicable logic in his

own, can be demonstrated through

"melodic analysis." Also on the

traditional side are the ostinati

and pedal-point harmonies, a

feature of ' Seraphita', used as

well in the third and fourth

songs, in the case of the latter

with a distribution of accents

spread through four lines of

violins and violas, an interesting

idea not developed in any later

work.

The innovatory side is most

handily exemplified in the

instrumentation. Consider the

spatial relationships. At the end

of ' Seraphita', the 24 violins

sustain a long note in the highest

range, while pizzicato cellos and

a xylophone play a repeated note,

and the basses play a descending

line to their lowest register. The

distance between highest and

lowest levels has never been

greater. The final, four-note

cadence, under the sustained high

violin note, begins with a

parallel downward half-step in ten

parts followed by the simultaneous

drop of an octave in four parts.

Yet the effect is the same as that

of a classical close.

Schoenberg himself singled out the

"preponderantly soloistic" style

of the orchestration. In the brief

second song, which reduces the

ensemble to only sixteen

instruments from sixty in the

first song, each part is a "solo",

until the broadening, climactic

middle section, underscoring the

word "Eitelkeit", where

both the lower treble and lower

bass lines are doubled. But the

size of the ensembles in each of

the four songs is remarkably

different, and only ' Vorgefühle'

requires a normal symphony

orchestra. In ' Seraphita', the

only woodwinds are clarinets. Six

of the same (mid-range) kind begin

the piece playing a unison

cantilena, an unheard of,

plaintive, whining sound, then fan

out to six parts. The articulation

and volumes change with every note

of the long-line legato melody, in

correspondence with the mainly

minor-second and minor-third

ambitus of the intervallic

construction. The new dimensions

of dynamics and mode-of-attack

opened up here, is one that

Schoenberg did not pursue.

In fact, clarinets are the

featured instrument in all of the

Songs, playing in extraordinary

combinations. Five of the only

sixteen instruments in ' Alle,

welche dich suchen' are clarinets

representing three different

ranges. In the third song, three

bass clarinets are joined by a

contrabass, adding new, richly

dark colours to the orchestral

palette. Three normal and one bass

clarinet are required in the last

song, and the clarinet colour

still remains dominant.

Heretofore, the art of

instrumentation had been concerned

chiefly with contrasts and

mixtures, not with exploring the

deployment of several of the same

instruments on the same part, nor

with the exploitation of family

combinations.

In 'Seraphita', the strings do not

include violas, and the 24 violins

are not divided into the

traditional firsts and seconds,

but into smaller groups, with the

important exception of two unison

passages, one of them in the

storm-music interlude, the other

in the stratospheric concluding

bars. The twelve cellos are divisi

until their last twelve bars,

which they play in unison. The

basses, which play very little,

nevertheless become the principal

melodic voice in two places.

Percussion instruments, most

prominently the xylophone, are

used only in ' Seraphita', where,

also, the only brasses are three

trombones, a single trumpet, and a

tuba.

The Four Songs are at an

opposite pole from Erwartung

(1909) and Gurre-Lieder,

Schoenberg's other great creation

for female voice and orchestra.

Whereas the text of the dramatic

monologue Erwartung is

comprised entirely of the thoughts

and anacoluthons of a hysteric -

the musical settings,

correspondingly, to fragments and

stops and starts - the texts of

the Op. 22 Songs (the three by

Rilke are beautiful poems in

themselves) inspired long-line

melodic phrases of a kind that

Robert Schumann would have

understood. But first of all the

instrumental (six-clarinet)

introduction to ' Seraphita' is

itself the longest-line melody

that Schoenberg had written since

his earliest years.

The musical images evoked by the

texts are remarkably traditional

in kind. The cymbal-crashes, the

loud, rapid, wide-interval bursts

in the brass, and the jagged forte

ones in the violins in 'Seraphita'

are not different in genre from

the storm music of Wagner. The

setting of Rilke's beautiful line,

"auf deiner Meere Einsamsein"

("the vastness of your oceans

lone"), which begins with the

recapitulation of the first three

notes of the vocal part in '

Seraphita' - the songs are linked

by the recurrence in each of the

same or similar melodic cells -

slowly rises in pitch with the

word "Meere", then on the

word "Einsamsein" falls in

a great arc to the deepest vocal

register.

In his 1932 analysis, Schoenberg

acknowledges that the "poetry

assisted my feelings, insights,

occurrences, impressions." Let it

be said that the musical emotion,

during World War I's darkest days,

is personal, in its feelings of

resignation and agitation -

conveyed by the orchestra at the

beginning of ' Vorgefühle' ("I

sense the winds which come and

must endure them") - and of the

sense of abandonment at the end of

the same song, where the composer

must have believed that the poem

was addressed directly to him:

…I can already sense

the storm, and surge like the

sea.

And

spread myself out and into

myself downfall

and

hurtle away and am all alone

In the

great storm.

Chamber Symphony No. 1, Op. 9

(1906)

Introducing the composer's

pre-atonal works, programme

annotators often begin by

attempting to explain the piece's

anticipation of atonality, while

at the same time tracing its

antecedents in Tristan and

Parsifal. But the single-movement

Symphony requires total

concentration on itself alone, and

no part of the listener's mind, if

he or she is to digest it fully,

can be spared for musings about

where the composer once was and

where he is going. It is the

densest, most compact and rapidly

moving music up to its time

(1906).

Schoenberg himself outlined the

form in terms of rehearsal numbers

in the score:

I

Sonata-allegro (Beginning to No.

38)

II

Scherzo (Nos. 38–60)

III

Development (Nos. 60–77)

IV

Adagio (Nos. 77–90)

V

Recapitulation and Finale (Nos.

90–100)

The overt

Wagnerisms in the Adagio

may seem surprising at this stage

in Schoenberg's evolution, but the

never-mentioned, though blindingly

obvious, Beethoven ancestry is

more germane. The propulsive power

and the tug and pull of impending

tonal-harmonic resolutions bring

to mind the work of no other

composer. So does the cohesiveness

of different movements within a

single one - the recapitulation of

the Scherzo in the Finale

of Beethoven's C minor

Symphony - the repeated

hammer blows near the end of

Schoenberg's exposition in the

passage for the horn up-beats to tutti

chords, which recalls the repeated

forte chords in the first movement

of the Eroica.

Utterly new in Schoenberg are the

sudden rhythmic interchanges in

the Scherzo, the transferring of

the time-value of the beat to a

note of greater (or lesser) value,

and the constantly changing tempi.

No sooner is a steady pulsation

established than the word

"steigernd" - quickening,

intensifying - appears, the mood

begins to shift, and the music is

soon charging ahead and off the

emotional fever chart.

In later years Schoenberg claimed

that the Symphony was "a

first attempt to create a chamber

orchestra". He might have added

"and the last", since no one has

subsequently composed anything

comparable to it. A criticism

sometimes leveled against the

piece is that an ensemble of ten

winds and five strings is

inherently unbalanced. Schoenberg

knew this, of course, but his

fifteen instruments never play

"one on one". In full ensemble

episodes they are carefully

doubled, which was the composer's

chief means of obtaining balanced

volumes, as well as

differentiations of colour.

Instruments of different timbres

play in unison in Bach cantatas.

Similarly, in one triple forte

unison passage near the beginning

of the Symphony the upper

woodwinds combine on a single

line, producing a new, wonderfully

plangent, sonority. Among the

novel doublings, those of the

flute and small clarinet in their

lowest registers with the bassoon

in a medium high one, and of a

violin playing a fast triplet

accompaniment figure pizzicato

together with the piccolo playing

it legato, must be mentioned. But

it should also be said that some

of Schoenberg's instrumental

demands have become possible only

with a new generation of virtuoso

players, a bassoonist who can

double-tongue groups of six notes

at a metronomic 160 to the beat, a

double-bassist whose treble

harmonics are full tones at exact

pitch instead of out-of-tune

pipsqueaks, a violinist who

executes wide intervals perfectly

in tune in the top register - and

with players who know the whole as

well as their own parts. Only then

does a coherent performance of the

piece become a possibility.

Robert Craft

|

|