|

| 1 CD -

8.43630 ZS - (c) 1987 |

|

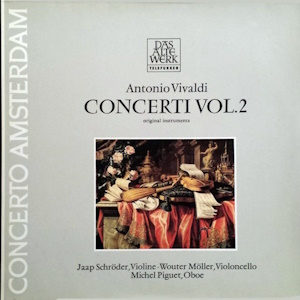

1 LP -

6.42355 AW - (p) 1978

|

|

CONCERTI VOL. 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

VIVALDI (1678-1741) |

Concerto

D-dur für Violine, Streicher und

Cembalo "Il grosso Mogul" (Der

Großmogul), F I/138 |

* |

|

13' 58" |

|

|

|

- Allegro (Kadenz:

Jaap Schröder)

|

|

6' 02" |

|

1 |

A1

|

|

- Grave.

Recitativo

|

|

3' 12" |

|

2 |

A2

|

|

- Allegro (Kadenz:

Jaap Schröder)

|

|

4' 44" |

|

3 |

A3

|

|

Sinfonia

h-moll für Streicher "Al S.

Sepolcro", F XI/7 |

|

|

3' 23" |

|

|

|

-

Adagio

|

|

1' 56" |

|

4 |

A4

|

|

- Allegro, ma poco

|

|

1' 27" |

|

5 |

A5

|

|

Concerto

h-moll für Violoncello, Streicher

und Cembalo, F III/9 |

** |

|

10' 25" |

|

|

|

- Allegro non

molto

|

|

4' 12" |

|

6 |

A6

|

|

- Largo

|

|

2' 37" |

|

7 |

A7

|

|

-

Allegro

|

|

3' 36" |

|

8 |

A8 |

|

Concerto

a-moll für Oboe, Streicher und

Cembalo, F VII/5 |

*** |

|

8' 38" |

|

|

|

-

Allegro non molto |

|

3' 47" |

|

9 |

B1 |

|

-

Larghetto |

|

2' 15" |

|

10 |

B2 |

|

- Allegro

|

|

2' 35" |

|

11 |

B3 |

|

Sinfonia

a 4 in Es-dur für 2 Violinen,

Viola und B.c. "Al Santo

sepolcro", F XVI/2 |

|

|

3' 53" |

|

|

|

- Largo molto

|

|

2' 10" |

|

12 |

B4 |

|

- Allegro, ma poco

|

|

1' 43" |

|

13 |

B5 |

|

Concerto

c-moll für Oboe, Violine,

Streicher und Cembalo, F XII/53 |

*/*** |

|

7' 03" |

|

|

|

- Adagio

|

|

2' 25" |

|

14 |

B6 |

|

- Allegro

|

|

1' 55" |

|

15 |

B7 |

|

- Adagio |

|

1' 10" |

|

16 |

B8 |

|

- Allegro |

|

1' 43" |

|

17 |

B9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Jaap

Schröder, Violine *

|

CONCERTO AMSTERDAM

(mit Originalinstrumenten)

|

Wouter Möller,

Violoncello **

|

- Michel Piguet,

Oboe

|

Michel Piguet,

Oboe ***

|

- Jaap Schröder,

Violine

|

|

- Ruth Hesseling,

Violine

|

|

- Alda Stuurop,

Violine

|

|

- Antoinette van

den Homnergh, Violine

|

|

- Linda Ashworth,

Viola

|

|

- Wouter Möller,

Violoncello

|

|

- Lidewy Scheifes,

Violoncello (Continuo in Cellokonzert)

|

|

- Jeroen van der

Linden, Violone |

|

- Bob van Asperen,

Violoncello |

|

Jaap SCHRÖDER,

Konzertmeister |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Doopsgezinde

Kerk, Haarlem (Netherlands)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Heinrich

Weritz

|

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Telefunken

- 6.42355 AW - (1 LP) - durata 47'

20" - (p) 1978 - Analogico

|

|

|

Edizione

"Reference" CD

|

|

Tedec

- 8.43630 ZS - (1 CD) - LC 3706 -

durata 47' 20" - (c) 1987 - AAD |

|

|

Cover |

|

Foto mit

freundlicher Genehmigung des

Museums für Kunst und Gewerbe

Hamburg |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Antonio

Vivaldi’s significance

as a composer is

scarcely in doubt any

longer: after all, few

musicians have staged

such an impressive

comeback as the prete

rosso, or Red

Priest, as Vivaldi was

known on account of the

colour of his hair. Yet

the rediscovery of the

works of Venice‘s most

famous maestro di

violino, about

whose turbulent life the

dramatist Carlo Goldoni

reports briefly in his

memoirs (Goldoni valued

him more as a virtuoso

violinist than as a

composer), began

inauspiciously, with

many of his concertos,

which are all of a

similar basic type,

eliciting little

interest or even

outright rejection. To

quote Walter Kolneder,

“it was the composers

least substantial works

that most incensed

Vivaldi‘s critics". It

was only when audiences

became acquainted with

many of his other

pieces, including the

programmatical Le

quattro stagioni

(Four Seasons) from Il

cimento dell'armonia e

dell’inventione

op. 8, written around

1725, as well as a

number of the composers

operas and sacred Works,

that this picture was

finally corrected.

The Violin Concerto in D

major, RV 208 is also

known as Il grosso

Mogul, a title

which, probably intended

as a joke, is found in

only a single copy.

Delightful though this

name may be, the work

itself is one of the

least well known of

Vivaldi’s many violin

concertos. The opening

Allegro is thematically

simple but virtuoso in

style, and is followed

by a recitative-like

slow movement in the

relative (Vivaldi was

particularly fond of B

minor), with a deeply

expressive melodic line.

The final Allegro is

dance-like in character.

The Work is notable not

least for the fact that

the solo instrument is

supported either by the

continuo alone or by a

loose accompaniment of

tutti violins.

Whether the Sinfonia in

B minor, RV 169 should

be accounted a concerto

or an example of

programme music must

remain an open question.

Its nickname Al

Santa Sepolcro

refers to the tradition

of reproducing the Holy

Sepulchre in churches

during Holy Week.

Vivaldi’s predilection

for chromatic writing,

the anguished and solemn

mood of the opening

section (Adagio molto)

and the thematic

reminiscences of the

Adagio molto in the

second section (Allegro,

ma poco) go far beyond

the average concertante

writing of many similar

works.

Also in B minor is the

Cello Concerto, RV 424.

Of Vivaldi's

twenty-seven works for

the instrument this is

one of the least well

known. The composer's

remarkable command of

cello technique and the

nature of the writing

for an instrument still

in the early stages of

its development may be

attributable to his

acquaintance with the

Italian cellist

Francischello. The heart

of this three-movement

work is its central

panel, a Largo which,

although only sixteen

bars long, is notable

for the way in which a

simple idea is richly

ornamented, while at the

same time affording an

oasis of calm. The

virtuoso demands placed

on the solo instrument

in the final Allegro are

even more formidable

than those found in the

opening movement. “With

the exception of a

handful of weaker

pieces," Walter Kolneder

writes, Vivaldi’s cello

concertos are “of the

highest musical quality.

In the technical demands

that they place upon

their performer, they

reflect the most

important stage in the

history of the

instrument and the

manner in which it is

played".

Vivaldi wrote a total of

twenty concertos for

solo oboe, strings and

harpsichord. According

to Kolneder, the Oboe

Concerto in A minor, RV

461 may have been

inspired by the high

level of woodwind

playing at the courts of

the Landgrave of

Hesse-Darmstadt, the

Duke of Lorraine and

Count Morzin of Bohemia

and is a particularly

fine example of

Vivaldi’s inventive

skill at writing for a

concertante solo

instrument. The opening

Allegro non molto will

surprise the listener

with its rhythmic

vitality and

succinctness of

expression, while the

following Larghetto in C

major exploits the

Scotch snap, a

syncopated figuration

very popular in its day.

Except in the opening

and closing bars of the

tutti, the orchestra is

limited to violins and

viola, which provide the

soloist with modest

support. In the final

Allegro, as in so many

other concertos by

Vivaldi, it is the

concertante style that

predominates. As in the

previous concerto, this

final movement places

greater technical

demands on the soloist

than the opening

Allegro.

Like the B minor

Sinfonia, the Sonata in

E flat major for two

violins, viola and

continuo, RV 130 has the

alternative title of Al

Santo Sepolcro.

It, too, is in two

movements, a Largo molto

and Allegro, ma poco,

that are stylistically

similar to some of the

early works of Viennese

Classicism. Indeed, many

of the features of

Vivaldi’s concertos or

sinfonias (the two terms

were used more or less

interchangeably by the

composer) anticipate a

development that was

later to find expression

in the Classical

bithematic sonata. A

model of self-contained

unity, the sonata’s

second movement is a

fine example of this

technique.

Manuscripts and copies

of Vivaldi’s

instrumental works have

been found in a number

of North European

libraries in recent

decades. The Concerto in

C minor, RV app.17 for

oboe and violin was

discovered in Lund

(Sweden) and published

by David Lasocki in

1973. Cast in the form

of a sonata da

chiesa, it may

remind its listeners, at

least at an initial

hearing, of a concerto

by Corelli or Handel.

Particularly noteworthy

is the urgency of the

second movement

(Allegro) and, as so

often with Vivaldi, the

hannonic sophistication

of the Adagio in G

minor, which serves, so

to speak, as a

dominant-key

introduction to the

gigue-like final

movement.

Helmuth

Wirths

Translation:

Stewart Spencer

|

|