|

3 LP's

- Telefunken 6.35584 EK (c) 1981

|

|

| 1 LP -

Toccata FSM 53 612 (p) 1975 |

|

| 1 LP -

Toccata FSM 53 613 (p) 1975 |

|

| 1 LP -

Toccata FSM 43 603 (p) 1976 |

|

| ORIGINALINSTRUMENTE -

Tasteninstrumente Vol. 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 1

|

|

|

|

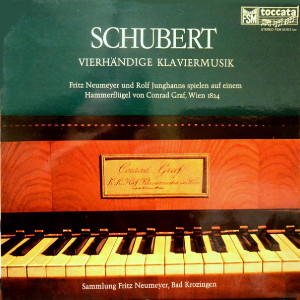

| Franz Schubert (1797-1828) |

Grand

Rondeau A-dur, Op. 107; D 951

*

|

|

11' 33" |

A1 |

|

Andantino

varié h-moll, Op. 84 Nr. 1; D 823

* |

|

8' 45" |

A2 |

|

Fantaisie

f-moll, Op. 103; D 940 *

|

|

18' 08" |

B1 |

|

-

Allegro molto moderato · Largo · Allegro

vivace · Tempo I |

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 2 |

|

|

|

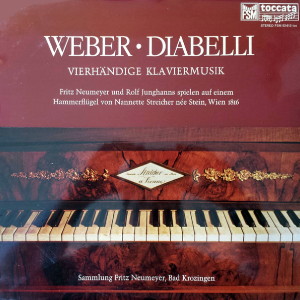

| Anton Diabelli (1781-1858) |

Sonate

D-dur, Op. 33 **

|

|

10' 22" |

C1 |

|

-

Allegro moderato |

3' 47" |

|

|

|

-

Andante cantabile |

2' 40" |

|

|

|

-

Rondo Allegretto |

3' 55" |

|

|

| Carl Maria von Weber

(1786-1826) |

Huit

pièces, Op. 60 **

|

|

32' 59" |

|

|

1.

Moderato |

2' 52" |

|

C2

|

|

2.

Allegro |

4' 17" |

|

"

|

|

3.

Adagio |

3' 55" |

|

"

|

|

4.

Allegro, tutto ben marcato |

4' 19" |

|

D1 |

|

5.

Alla Siciliana. Allegro |

3' 56" |

|

"

|

|

6.

Tema Variato. Andante |

3' 09" |

|

"

|

|

7.

Marcia. Maestoso |

5' 23" |

|

"

|

|

8.

Rondo. Scherzando vivace |

5' 08" |

|

"

|

|

Long Playing 3 |

|

|

|

| Anton Diabelli (1781-1858) |

Sonata

C-dur, Op. 37 *

|

|

12' 27" |

E1 |

|

-

Allegro moderato · Andante cantabile

· Rondo · Allegretto |

|

|

|

| Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

|

Grande

Marche es-moll, Op. 40 Nr. 5; D

819 **

|

|

10' 02" |

E2 |

| Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) |

Zwei

Walzer, Op. 39 Nr. 15 und 16

***

|

|

3' 32" |

E3 |

| Friedrich Kuhlau (1786-1832)

|

Sonate

G-dur ****

|

|

8' 20" |

F1 |

|

-

Allegro · Arioso · Rondo · Allegro

|

|

|

|

| Carl Maria von Weber

(1786-1826) |

Andante

con Variazioni, Op. 10 Nr. 3

***** |

|

5' 35" |

F2 |

| Muzio Clementi

(1752-1832) |

Sonate

Es-dur ******

|

|

8' 50" |

F2 |

|

-

Allegro maestoso · Andante · Tempo

di Menuetto |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fritz

NEUMEYER & Rolf

JUNGHANNS,

Vierhändige Klaviermusik

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Long Playing 1)

|

(Long Playing 2)

|

(Long Playing 3) |

| -

Hammerflügel von Conrad

Graf, Wien 1824 *

|

-

Hammerflügel

von Nannette

Streicher,

Wien 1816

**

|

-

Hammerflügel

von Michael Rosenberger,

Wien 1810 (restauriert

von Rudolf Dobernecker)

* |

|

|

-

Hammerflügel von Conrad Graf, Wien

1824 (restauriert von Martin

Scholz) ** |

|

|

-

Hammerflügel von J. B. Streicher

u. Sohn, Wien 1864 (restauriert

von Hugo Haid) ***

|

|

|

-

Schrankflügel, unsigniert,

süddeutsch um 1820 (restauriert

von Rudolf Dobernecker) ****

|

|

|

-

Tafelklavier von Joseph Bogner,

Freiburg/Br. um 1840 (restauriert

von Rudolf Dobernecker) *****

|

|

|

-

Hammerflügel von John Broadwood

and Sons, London 1817 (restauriert

von Kurt Wittmayer) ******

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Schlos

Bad Krozingen (Germania) - 1975

(long playing 1 & 2)

/ 1976 (long playing 3)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision

|

|

Paul

Dery |

|

|

Edizione LP |

|

TELEFUNKEN

- 6.35584 EK - (3 LP's - durata

38' 26", 43' 21" & 48' 46") -

(p) 1975/76 - (c) 1981

|

|

|

Originale LP

|

|

TOCCATA

- FSM 53 612 - (1 LP - durata

38' 26") - (p) 1975 -

Analogico (long playing 1)

TOCCATA - FSM 53 613 - (1 LP -

durata 43' 21") - (p) 1975 -

Analogico (long playing 2)

TOCCATA - FSM 43 603 - (1 LP -

durata 48' 46") - (p) 1976 -

Analogico (long playing 3)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

Production

by Toccata.

|

|

|

|

|

Long

Playing

1

The

Fantaisie in f

minor and the

Grand Rondeau in A

major are the two

great pieces for

piano for four

hands, which Franz

Schubert wrote in

1828, the year of

his death. They

are highlights in

the rich and,

until the

beginning of our

century, much

loved genre of

four hands piano

music. The proud

rhythms of the

Hungarian

folkmusic and a

melancholic Puszta

atmosphere

alternate with

sweet and blissful

Viennese melodies

and alpine country

triad motives.

Added to this was

the inclination of

the late Schubert

towards the

perfection of form

by use of

counterpoint.

These elements are

changed in the

Grand Rondeau into

an idyllic and in

the Fantaisie into

a tragic form and

prevade the

Andantino varie as

well.

All these pieces

originate from the

romantic spirit of

the 19th century

in the sense of E.

Th. A. Hoffmann’s

saying: music

opens to man a

"secret realm of

spirit"; and as

stated in

Schubert’s song

"An die Musik" it

takes man away

into a "better

world". Schubert

reaches this aim

of the romantic

musician in an

ingenious way

through his

harmony, which is

enlarged through

new tonal

connexions in an

unimagined manner.

The experience of

a romantic magic

of sound reaches

its height when

the piano music,

written by

Schubert, is

played on an

instrument that

corresponds to the

ideal of the

composer: the

pianoforte

(Hammerflügel) by

Conrad Graf. This

masterpiece of

Viennese

piano-building has

a transparence of

overtone and the

easy sensitive

touch of the

classical Viennese

pianoforte. It

possesses,

however, a

cantabile

abundance and an

unique variability

of timbre, which

is produced

through the style

of registration

and the use of the

so-called

"changements" (see

below).

We can conclude

from the specially

subtle dynamic

instructions that

Schubert composed

for such an

instrument as he

asks for

differenciated

shades up to a

threefold

pianissimo with

diminuendo.

Our instrument

with its pure

wooden

construction, the

leather covered

hammers and the

thin strings was

built by Conrad

Graf in the year

1824. The four

pedals change the

sound in the

following manner:

1. Removal of the

damper.

2. Pianoregister:

a piece of cloth

is slide between

hammers and

strings and this

produces a soft

and delicate tone.

3.

Bassoonregister: a

parchment scroll

is pressed upon

the bass strings

and this produces

a buzzing sound.

4. Displacement of

the keys: For

every tone exist

three strings.

When the keys are

displaced only two

or one string is

touched.

The instrument was

restored by Martin

Scholz, Basel, and

Rudolf

Dobernecker,

Freiburg im

Breisgau.

Long

Playing 2

On April

16th 1813, Carl

Maria Weber wrote

to his brother

from Vienna: "I

have just bought

two superb

instruments, a

Streicher and a

Brodmann. In a

single day I must

have seen a good

fifty different

pianos, and not

one of them could

hold a candle to

these two."

The piano built by

Nannette Streicher

née Stein which is

played on this

recording is a

sister instrument

to the one Weber

bought. Nannette

Streicher was the

daughter of the

Augsburg organ-

and piano-builder

Johann André Stein

(1728-1792), the

most famous

craftsman of his

time, who was also

highly esteemed by

Mozart. Nannette,

who was born in

1769, was already

being acclaimed as

a child prodigy

for her

piano-playing at

the age of eight.

However, Mozart

judged her rather

critically on his

visit to Augsburg

in 1777: "She has

the ability to be

a great musician,

she has genius,

but she won’t

achieve anything

in this way." She

did not, however,

become a piano

virtuoso, but

learnt the craft

of piano-building

from her father,

taking over the

workshop after his

death. In 1794 she

married Andreas

Streicher, a

boyhood friend of

Schiller’s. (It

was Streicher who

helped Schiller to

flee from

Stuttgart, where

he had been

forbidden to write

literature outside

the scope of his

work as an army

doctor, to

Mannheim in 1782.)

The piano workshop

was moved to

Vienna, the centre

of contemporary

musical life, and

the firm soon

gained fame

throughout Europe

under the name

"Nannette

Streicher née

Stein a Vienne".

Alongside Weber

and Beethoven (a

personal friend

and protégé of

Nannette’s),

E.Th.A. Hoffmann,

Zelter, Reichardt

and many others

were clients of

the firm, and

prized its

instruments

greatly. Thus the

Streicher salon

became a

rendezvous for the

music-lovers of

Vienna.

The piano pieces

for four hands by

the successful

composer and music

publisher Anton

Diabelli are noble

music for just

such a refined

audience: salon

music which avoids

descending into

shallowness and

superficiality.

The orchestral

fullness and

diversity of

timbres that

characterize

Streicher

instruments may

have offered

particular

inspiration to the

master of the

Romantic

orchestra, Carl

Maria von Weber.

His Huit

Piéces op. 60

combine

superlative

compositional

technique with

allusive poetic

content: they can

be regarded as

scenes from

Weber’s operas

transferred into

the purely

instrumental

medium.

1) The moderato

can be

understood as a

forest scene

which combines

the idyllic and

the sinister.

2) The allegro,

with its noble

march rhythms,

recalls the

knight Huon of

Bordeaux from

the composer’s Oberon.

3) Oberon

himself, King of

the Elves, leads

his retinue to

the dance.

4) Years

before Schubert

wrote his piano

pieces for four

hands, inspired

by Hungarian

folk music,

Weber composed

this allegro,

so full of the

proud,

melancholy

sounds of the

steppes.

5) The

rocking rhythm

of the siciliana

recalls the song

of the mermaids

from Weber’s

opera Oberon.

6) The

theme of the

brilliant and

witty variations

is a popular

song of Weber’s

own invention.

7) The

demonic march is

a reflection of

history: foreign

troops marching

through Vienna,

capital of the

then

Austro-Hungarian

Empire. In the

trio an image of

freedom seems to

hover before us.

8) The rondo

is an early

waltz, in which,

as in nearly all

of Weber’s

compositions,

the sinister and

the demonic are

evident.

The

Streicher piano’s

richness of timbre

results from the

so-called

"transformations",

which are employed

in a similar way

to the registers

of an organ or

harpsichord, and

are achieved by

the use of four

pedals:

l)

Suspension of

the damping:

only employed as

a special

effect, so that

the strings

sound noisily

confused.

2) Piano

register: a

strip of cloth

is inserted

between the

leather-covered

hammer and the

strings, giving

a soft and

suppressed tone.

3)

Bassoon

register: a roll

of parchment is

pressed against

the strings in

the bass,

producing a

droning sound

similar to that

of the old

bassoon.

4)

Displacement:

the keyboard and

the piano action

are shifted so

far to the

right, that not

all three

strings

available for

each sound are

struck, as is

usual, but only

two, or even one

(una corda).

The piano tone

becomes more

delicate and

transparent as a

result.

Long

Playing 3

The term

"Hammerklavier"

originally meant

the same as

"pianoforte" or

"fortepiano", and

was used by

Beethoven as a

Germanicization of

the latter names,

foreign to the

German language.

Nowadays,

"Hammerklavier"

covers the range

of pianotypes

current from

roughly the time

of Mozart to that

of Brahms, which

were predecessors

of our modern

piano, but not the

20th century piano

itself, although

this is, strictly

speaking, a

Hammerklavier too.

The early piano

types from the

time of Mozart

still resemble the

harpsichord in

construction and

in the sound

produced.They were

also referred to

as "cembalo col

piano e forte",

and subsequently

as "pianoforte".

The instrument’s

development

continued by way

of many

intermediate

stages: in an

effort to attain a

greater volume of

sound, pianos were

gradually built

with thicker

strings, larger

hammers and a

stronger

soundboard. All

this in turn

required a more

solid

construction: the

light box-like

harpsichord design

began to be

replaced by a

wooden frame,

which was

initially light,

but became

increasingly

sturdy.

Eventually, iron

stays were

necessary to

reinforce the

frame; iron plates

were then added,

and around 1860

the last step was

taken - a full

iron frame.

Likewise, the

mechanics of the

piano became

increasingly heavy

and more complex,

the last

development being

the introduction

of the double

repeating action

by Sebastian Erard

in 1823. It was

now possible to

play much faster

and louder, a

development which

corresponded to

growing virtuosity

in the medium.

Equally, the

change in the tone

sought after by

musicians - a

change which

occurred with

other instruments

at the time -

meant that certain

individual sounds,

like combined

harmonics and a

clear, sentimental

sound, were

abandoned in

favour of a more

robust sound which

was rather less

transparent.

The development of

the instrument

from the

harpsichord-like

fortepiano to the

armour-plated

grand piano only

took about eighty

years, and it was

in this period

that most of the

piano music played

today was written.

Mozart, Haydn,

Beethoven,

Schubert, Schumann

and even Brahms

owned instruments

which were

noticeably

different from our

modern piano. They

composed for these

pianos, and, in

their piano

writing, took into

account the tonal

characteristics of

their particular

instrument. The

first half of the

19th century was a

period of rapid

change for piano

building and piano

music alike.

This fact is most

clearly

demonstrated by

the instruments

built in Vienna,

the contemporary

centre of the

piano-building

industry: Viennese

pianos are,

without exception,

distinguished by a

sensitive,

delicate action.

The grand piano

built by Michael

Rosenberger of

Vienna in 1810

still has the

lightness and

transparency of

the Mozartean

instrument, but it

already produces a

more powerful

sound, and great

alterations to the

tone can be

achieved by the

use of no less

than six different

pedals. Among the

tone changes

possible are the

distinctive burr

of the bassoon

register (a

parchment roll is

placed against the

strings in the

bass) and the

so-called

janizzary

register, produced

by a large drum

and chimes built

into the piano.

The latter, also

called "Turkish

music", brings

exotic colouring

into the

sauntering rondo

of the

entertaining

sonata by

Diabelli, who was

a successful music

publisher as well

as a composer.

The Conrad Graf

grand piano was

only built some

fifteen years

later, but it is

quite differently

constructed: it is

heavier than the

Rosenberger

instrument, and

the sound has more

of the cantabile

about it; it is

more romantic and

somehow bulkier,

yet it remains

able to

differentiate

notes right down

to a

clavichord-like

pianissimo. Graf’s

instruments were

highly esteemed by

Schubert, whose

exact dynamic

specifications in

his scores,

extending to ppp,

certainly demand

the polychromatic

registers of the

Graf piano.

Schubert’s

mournful E-flat

minor march is

influenced by the

main theme of the

composer’s

"Wanderer"

fantasy.

A sister

instrument to our

Johann Baptist

Streicher piano

dating from 1864

stood in Brahm’s

appartment in

Vienna. It is

still without an

iron frame, and

still has the

"Viennese action",

as opposed to

Erard’s double

repeating action,

and

leather-covered

felt hammers.

Brahm’s waltzes

for four hands

show felicitously

how the phlegmatic

Hamburger made

himself at home in

the Vienna

ambience.

The upright piano

was derived from

the Hammerklavier,

and was built in a

variety of forms

in the 19th

century: there was

the lyre-piano,

the giraffe-,

pyramid- and

cabinet-pianos.

All four models

functioned not

only as musical

instruments, but

as decorative

furniture in the

Biedermeier

period. And it was

genuine

"Biedermeier

music" that came

from the pen of

Friedrich Kuhlau,

a native of Uelzen

in Lower Saxony.

Kuhlau, later

Kapellmeister at

the Danish royal

court, wrote a

touching

pot-pourri that

reflects this

ornamental but

superficial

period: the

fairy-tale world

of Hans Christian

Andersen mixed

with the colourful

bustle of the

Tivoli Gardens.

In terms of sound,

there is scarcely

any difference

between the

upright and the

grand pianos built

at the time. The

smaller baby grand

as we know it

today was a later

phenomenon. Its

predecessor was

the square piano,

an instrument

which derived its

external

appearance from

the clavichord -

in fact, it looks

like a clavichord

without legs. More

modest in sound

than the full-size

grand pianos, the

square piano is

ideal for playing

small-scale,

unpretentious

pieces like

Weber’s attractive

Andante con

Variazioni.

The great rivals

of Vienna built

instruments since

the 17th century

had been English

pianos: these were

from the outset

equipped with a

less sensitive,

more robust

action, which made

richer-sounding

playing possible,

and in the end

they completely

supplanted the

Viennese pianos on

account of their

more ample sound.

The Broadwood

piano played here

is the same model

as the instrument

which the London

piano-builder

Broadwood sent

Beethoven as a

gift in 1817: for

a while the piano

afforded renewed

pleasure to the

composer, who was

steadily going

deaf. The Italian

composer Clementi,

whom Beethoven

highly respected,

was also the

joint-owner of a

piano factory, and

built similar

instruments.

|

|

|