|

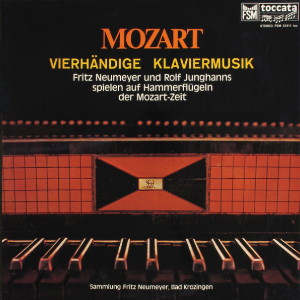

3 LP's

- Telefunken 6.35576 EK (p) 1981

|

|

| 1 LP -

Toccata FSM 43 604 (p) 1975 |

|

| 1 LP -

Toccata FSM 53 611 (p) 1975 |

|

| ORIGINALINSTRUMENTE -

Tasteninstrumente Vol. 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 1

|

|

|

|

| Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach

(1714-1788) |

12

Variationen über "Les folies

d'Espagne", Wq 118 *

|

|

10' 10" |

A1 |

| Johann Christoph

Friedrich Bach (1732-1795) |

14

Variationen über "Ah, vous

dirai-je Maman", Wohlf. Verz. XII,

2 ** |

|

9' 14" |

A2 |

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

|

Rondo

D-dur, KV 485 ***

|

|

5' 21" |

A3 |

| Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach |

Rondo

III - aus "Clavier-Sonaten

nebst einigen Rondos fürs

Fortepiano, für Kenner und

Liebhaber, Zweyte Sammlung", Wq 56 °

|

|

9' 35" |

B1 |

|

Sonata

III - aus "Clavier-Sonaten

nebst einigen Rondos fürs

Fortepiano, für Kenner und

Liebhaber, Zweyte Sammlung", Wq 56 ° |

|

6' 33" |

B2 |

| Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart |

Sonate

C-dur, KV 545 |

|

12' 42" |

B3 |

|

-

Allegro · Andante · Rondo:

Allegretto |

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 2 |

|

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart |

Sonate

D-dur, KV 381 +

|

|

14' 50" |

C1 |

|

-

Allegro · Andante · Allegro

molto |

|

|

|

|

Andante

G-dur mit fünf Variationen, KV 501

++

|

|

8' 50" |

C2 |

|

Sonate

C-dur, KV 521 +++

|

|

23' 30" |

D1 |

|

-

Allegro · Andante ·

Allegretto |

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 3 |

|

|

|

| Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710-1784) |

Acht

Fugen für Cembalo *

|

|

17' 10" |

E1 |

|

-

(Allegro moderato) · (Presto) ·

Adagio · Allegro |

|

|

|

| Johann Abraham Peter

Schulz (1747-1800) |

Allegretto

Nr. 5 - aus "Sechs

Klavierstücke", Op. 1 **

|

|

5' 40" |

E2 |

| Johann Christian Bach

(1735-1782) |

Sonate

B-dur, Op. 17 Nr. 6 ***

|

|

18' 45" |

F1 |

|

-

Allegro |

6' 13" |

|

|

|

-

Andante |

8' 20" |

|

|

|

-

Prestissimo |

4' 12" |

|

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart |

Fantasie

d-moll, KV 397 ****

|

|

6' 10" |

F2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Rolf

JUNGHANNS */**/***

|

Fritz

NEUMEYER

|

|

Fritz

NEUMEYER °/°°

|

Rolf JUNGHANNS

|

Rolf

JUNGHANNS

|

|

|

|

(Long Playing 1)

|

(Long Playing 2)

|

(Long Playing 3) |

-

Tangentenflügel von Späth &

Schmahl, Regensburg 1801 *

|

-

Hammerflügel, unsigniert,

süddeutsch um 1780 +

|

-

Cembalo nach Blanchet, Paris um

1730, von Willard Martin,

Bethlehem/Pennsylvania *

|

| -

Tafelklavier, sog. Clavecin Royale

von Gottlob Wagner, Dresden 1785

** |

-

Hammerflügel von Joh. André Stein,

Augsburg um 1785 ++

|

-

Hammerflügel von Matthäus

Heilmann, Mainz um 1785

**/**** |

| -

Hammerflügel, unsigniert (Matthäus

Heilmann, Mainz?), um 1780 1785

*** |

-

Hammerflügel von Johann Gottlieb

Fichtl, Wien um 1795 +++

|

-

Hammerflügel von John Broadwood

& Son, London 1798 ***

|

| -

Bundfreies Clavichord von Carl

Schmahl, Regensburg?, Ende 18.

Jahrh. ° |

(Instrumente

restauriert von Rudolf Dobernecker)

+ /++ |

|

| -

Gebundene Clavichord, unsigniert,

süddeutsch um 1800 °° |

(Instrument

restauriert von Martin Scholz) +++

|

|

| (Alle Instrumente

wurden restauriert von Rudolf Dobernecker,

Freiburg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Schlos

Bad Krozingen (Germania) - 1975

(long playing 1 & 2) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision

|

|

Paul

Dery |

|

|

Edizione LP |

|

TELEFUNKEN

- 6.35576 EK - (3 LP's - durata

53' 35", 47' 10" & 47' 55") -

(p) 1975/81 |

|

|

Originale LP

|

|

TOCCATA

- FSM 43 604 - (1 LP - durata

53' 35") - (p) 1975 -

Analogico (long playing 1)

TOCCATA - FSM 53 611 - (1 LP -

durata 47' 10") - (p) 1975 -

Analogico (long playing 2)

TELEFUNKEN - 6.35576 EK - (3°

LP - durata 47' 55") - (p)

1981 - Analogico (long playing

3)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

Production

by Toccata.

|

|

|

|

|

Keyboard

Music about

1780

Keyboard

music circa 1780

is characterized

by the

simultaneous

existence of a

number of

different styles.

The galant

style, inspired by

the French

intellect, took on

its subjective

animation from

German

"sentimentality"

and, by way of

integrating with

the arioso

and buffo

elements of the

Italian style,

flowed into

Mozartean

classicism - a

process which,

above all,

characterized the

work of the sons

of J. S. Bach. The

multiplicity of

styles in

existence in the

1770s and 1780s

did not only

influence the

actual composition

of keyboard music,

it also affected

the construction

of the instruments

themselves.

Harpsichord,

fortepiano,

clavichord, square

piano and a

strange hybrid

like the so-called

"tangential"

clavichord all

existed alongside

each other. The

allocation of

instrument was

left to individual

good taste -

always the

ultimate arbiter

in the 18th

century.

The "Folia", also

called "Les folies

d’Espagne" since

the 17th century,

is a melodic model

which has been

used by many

composers as a

melodic and

harmonic framework

for the

composition of

variations. Carl

Philipp Emanuel

Bach wrote his

twelve variations

on the "Folies" in

1778. The opulence

of the rhythmic,

harmonic, dynamic

and even

polyphonic

variation devices

which Bach employs

are without

parallel for their

time. Each of the

twelve variations

seems to be a

quite individual,

musically

independent

version of the

basic theme, yet

the impression of

unbroken, cyclical

unity is kept

intact.

In about 1785,

Emanuel’s younger

brother Johann

Christoph

Friedrich Bach

wrote a set of

variations on the

French song "Ah,

vous dirai-je

Maman", which was

universally

popular at the

time. In contrast

to the "Folies"

variations, J. C.

F. Bach’s work

represents a less

exacting variation

model, intended

for performance by

the amateur

music-lover. In

the fourteen

pieces, most of

which are written

for two parts, the

variations on the

song melody are

principally

achieved by

figurations to the

upper part which

conform throughout

to a

characteristic

pattern. This

cycle seems today

to be a

particularly

delightful example

of the art of late

18th century

society.

Mozart’s D-major

Rondo K. 485,

which he wrote in

1787, and the

C-major Sonata K.

545, which was

composed a year

later, both

combine Italian cantabile

with the

inventiveness and

sensitivity of C.

P. E. Bach, whom

Mozart revered all

his life as one of

his most important

intellectual

teachers. The

D-major Rondo also

documents the

efforts of the

classical composer

to divest the

rondo of its

inherited

character - that

of an orderly

progression - and

to transform it by

means of clever

harmonic

disposition, and a

highly developed

technique of

thematic

elaboration, into

a self-contained

cyclical form

comparable with

the sonata.

This is

particularly true

of the rondos from

the compositions

for "Kenner und

Liebhaber" -

connoisseurs and

music-lovers -

which were

published by C. P.

E. Bach from 1779

onwards. The Rondo

in A from the

second collection

and the sonata

following it

exhibit the

character of free

fantasies; their

restrained,

elegiac mood seems

to offer a

presentiment of

the Romantic era.

Hannsdieter

Wohlfahrth

Keyboard

Music for four

hands by W. A.

Mozart

On October

17, 1777 Mozart

wrote to his

father from

Augsburg,

describing his

visit to the organ

and pianoforte

maker, Johann

André Stein, whose

pianofortes he

could hardly

praise enough.

These instruments,

with which Mozart

was so pleased and

upon which he

played with such

great

satisfaction,

resemble more the

harpsichord than

the present-day

modern piano. They

are built entirely

of wood, with

extremely thin

sound-boards and

strings. From the

exterior they are

hardly

distinguishable

from harpsichords

of the time. The

strings are struck

by small hammers;

the hammers being

about eight times

smaller than those

of the modern

piano and covered

with hard leather

rather than felt.

These differences

in construction

allow the

"hammerclavier" of

Mozart’s time a

greater presence

of overtones, thus

a clearer sound as

well as allowing

for a greater

rhythmic

precision.

The pianoforte of

the Mozart era has

a much lighter

touch than the

modern instrument

and requires a

very different

playing technique.

It has two knee

levers which are

to be treated as

"registers" or

"stops"; one

raising the

dampers, the other

moving a strip of

cloth between the

hammers and the

strings (buff

stop).

The musical style

"for four hands"

makes special use

of all the

different tonal

effects which the

instruments of the

Mozart era offer.

Mozart had already

written pieces for

two on one

instrument as a

child, although he

is not the

inventor of the

style as his

father Leopold had

claimed. The

Sonata in D,

written in

Salzburg at the

age of 16 , is

here performed on

an early Mozart

"hammerflügel"

from the

Stein-School;

whereas the

variations,

composed 1786, are

performed on an

actual Stein

instrument. Mozart

sent the Sonata in

C, a later work,

to his friend,

Gottfried von

Jacquin, with the

accompanying text

"be so kind as to

give this sonata

to your sister -

she should set

about learning it

as soon as

possible, since it

is rather

difficult". It is

here performed on

a pianoforte which

closely resembles

Mozart’s own

instrument, built

by Anton Walter in

Vienna.

Siegfried

Schmalzriedt

Johann

Abraham Peter

Schulz:

Allegretto

A-minor

Johann

Abraham Peter

Schulz, to whom we

owe the musical

setting of "Der

Mond ist

aufgegangen" by

Matthias Claudius,

is best known for

his "Lieder im

Volkston" (folk

songs), which

where published in

three volumes

between 1782 and

1790. In a

biographical

sketch of Schulz

which appeared in

the musical

journal

"Allgemeine

Musikalische

Zeitung"

immediately after

the composer’s

death, Johann

Friedrich

Reichardt recalls

how he and Schulz

adhered faithfully

to the prescribed

rules of sonata

form in their

piano writing in

the 1770s. "How

often we laughed

later over our

conventional

belief in the

musical forms

sanctified by the

Berlin School!

When I had played

my sonata to

Schulz as far as

the first section

of the last

movement, he said

’Now all we need

is a good

modulation in a

related minor key

and then a

successful return

to the main key

for repetition of

the best passages

in the first

section, and voilà!

- the sonata is

comme il faut.'

" The

Allegretto in

A-minor, the fifth

of Schulz’ "Sechs

Klavierstücke" Op.

1 (1776), is one

of the same sonata

movements comme il

faur which the

composer and

Reichardt were

subsequently to

smile at in

ridicule of their

earlier efforts.

But we should not

take Schulz’

verdict on a style

of composition of

which he was

previously an

ardent follower

too seriously, but

should rather note

his touchiness

where any kind of

schematic

composition was

concerned.

"Truthfulness and

moving

simplicity", which

Reichardt points

to as Schulz’

noblest artistic

virtues, also

serve to

characterize the

Allegretto in

A-minor, a piece

which shows the

influence of C. P.

E. Bach in both

form and

expressive

content. Only that

everything is

somewhat simpler

than what we are

used to from the

harpsichordist of

Frederick the

Great, more for

the bourgeois

amateur than the

virtuoso player.

Siegfried

Schmalzriedt

Wilhelm

Friedemann

Bach: Eight

Fugues

Composing

fugues seemed to

the advocates of

the new

"sensitive" style,

post-1735, to be

"outmoded

pedantry". Music

ought to be "a

real outpouring of

emotion" and not

just "fugal

noises". Wilhelm

Friedemann Bach,

the eldest son of

Johann Sebastian,

followed a third

course of action

in his eight

three-part Fugues,

which he dedicated

in 1782 to

Princess Anna

Amalie of Prussia,

the musically

gifted sister of

Frederick the

Great: he

emotionalized the

fugue. We possibly

owe this

experiment, which

many people must

have found

paradoxical, to a

characteristic of

W. F. Bach’s; as

Carl Friedrich

Zelter put it, in

a letter to

Goethe, "As a

composer, he liked

to be original at

all costs." It

seems more likely,

though, that Bach

was consciously

continuing a

development

initiated by his

father, which is

particularly

noticeable in the

second part of

"The Well-Tempered

Clavier" (1742)

and in "The Art of

Fugue" (1749/ 50)

- namely, the

individualisation

and increasing

characterisation

of the fugue.

Obviously, the

attempt to expand

a contrapuntally

bound genre such

as the fugue so

that, like sonata

movements, rondos

and "fantasies",

it had the power

to "speak" and

"move" the

listener, required

certain

relaxations of its

strict formal

structure. In W.

F. Bach’s case

these amount to

the abandonment of

the independent

obbligato

counter-subject,

the renunciation

of a schematically

determined

ordering of notes

and parts, and the

opening out of the

intermezzi into

autonomous,

contrasting

sections of the

music. In spite of

these basic

features being

common to all

eight fugues in

the set, Bach

presents us in

each one with a

new reconciliation

of emotional

expression and

fugal form. The

Fugue VIII in

F-minor is

particularly

remarkable: its

status as a

masterpiece was

recognised by

Mozart, who

arranged the work

for strings (his

K. 404 a). The

eighth fugue is

also the one which

does the most

handsome justice

to W. F. Bach’s

concept of a fugue

saturated with

sentiment. The

structural

requirements of

fugue form are

fulfilled by a

chromatically

descending

subject, which

returns,

tightly-woven, in

the second half of

the piece.

Exceeding all

conventional

bounds, Bach links

contrasting,

freely expressive

sections to the

fugal subject to

achieve a quite

unprecedente

overall effect.

Siegfried

Schmalzriedt

Johann

Christian

Bach: Sonata

B-flat major

It took a

long time for

Johann Christian

Bach’s place in

musical history to

be recognised. The

nineteenth century

regarded this

youngest son of J.

S. Bach as an

apostate who had

turned his back on

solid musical

craftsmanship and

had yielded to the

lures and fashions

of the wide world.

Only since the

beginning of the

twentieth century

has he commanded

respect as one of

the creators of

the

sentimental-galant

instrumental

style, a style

which marked the

transition from

the high Baroque

to Viennese

classicism, and,

with its

aesthetics of

conscious

simplicity and

direct

expressiveness,

founded a new

musical ideal.

Mozart was more

than briefly

influenced in his

youth by the

"Milan" or

"London" Bach, and

retained a

lifelong regard

for him which was

shared by few of

his

contemporaries.

J. C. Bach’s piano

music is both

graceful and full

of moderation: it

never drifts off

into

superficiality,

nor into deep

passion. The six

sonatas of each of

the two sets for

unaccompanied

clavier, op. V

(published 1768)

and op. XVII (ca.

1779) are intended

for either

harpsichord or

fortepiano, as was

the custom at the

time; the music,

however, gives the

impression that

Bach had in mind

the modern

instrument, which,

with its rich

tonal nuances,

lends itself

better to dynamic

contrast. The

frequent Alberti

basses and the

abundant arpeggios

also suggest the

fortepiano as the

most suitable

instrument. In

formal terms,

these keybord

sonatas exemplify

what was, at the

time, still a

fairly new genre

at an advanced

stage of

development.

Although Bach’s

music is anything

but immature, the

fluctuating number

of movements in

the works

(sometimes two,

sometimes three)

and the varying

form of the

finales show that

the piano sonata

had not yet

established itself

as a musical form.

The subjects of

the main movements

of the sonatas

contrast

distinctly with

one another, but

the development

remains

rudimentary. The

elegant, graceful

writing and the bel

canto

melodies derive

from Italian

music, and the

sonatas do not

require a

brilliant

virtuoso: in fact,

Bach’s

contemporary

Charles Burney

claimed, with a

degree of

exaggeration, that

they could be

performed "by

ladies without too

much trouble".

They do, however,

demand a pianist

capable of

sensitive,

eloquent playing.

In a work like the

B-major sonata,

op. 17/ 6, only a

truly sensitive

pianist will be

able to realise

the restrained,

almost rapturous

expression, and

the sensuous

cantabile, so

lyrical in the

slow movement,

that so fascinated

the young Mozart.

Wolfgang

Ruf

Wolfgang

Amadeus

Mozart:

Fantasie

D-minor

Mozart’s

D-minor piano

piece K. 397 is

one of a handful

of works in which

Mozart enters into

the realms of

fantasy. They are

the fruits of a

period, beginning

early in 1782,

during which

Mozart devoted

himself to

intensive study of

the works of Bach

and Handel, and of

their North German

successors, above

all the master of

free fantasy-form,

C. P. E. Bach. The

work is clearly

divided into three

parts: a brief

introductory Andante

made up of

arpeggio chords,

almost

improvisational in

character, is

followed by two

sharply

contrasting

melodic sections,

a plaintive Adagio,

whose melancholy

is not to be

banished, not even

by wild presto

runs over the

whole keyboard,

and a charming,

serene Allegretto

in the major,

rounded off by a

short cadenza,

which releases the

tension built up

in the first two

movements. The

unrestrained

rhapsody of the

work is not an end

in itself, but

rather, in its

permeation of the

music’s

recurringly rigid

lyrical structure,

gives impulse to a

gradual process of

mental relaxation.

Thus the piece

which seems at

first sight so

unpretentious,

even aphoristic,

requires a

performance of

great delicacy and

a tender,

expressive tone

such as is only

offered by

fortepianos built

in southern

Germany and

Austria with the

so-called

"Viennese action".

Wolfgang

Ruf

|

|

|