|

3 LP's

- Telefunken 6.35521 EK (p) 1980

|

|

| 1 LP -

Toccata FSM 53 623 (p) 1976 |

|

| 1 LP -

Toccata FSM 53 619 (p) 1975 |

|

| ORIGINALINSTRUMENTE -

Tasteninstrumente Vol. 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 1

|

|

|

|

| Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) |

Präludium

und Fuge g-moll, BuxWV 163 |

|

8' 30" |

A1 |

| Friedrich Wilhelm

Zachow (1663-1712) |

Suite

h-moll |

|

9' 10" |

A2 |

|

-

Allemande · Courante · Sarabande ·

Fuga Finalis |

|

|

|

| Georg

Friedrich Händel (1685-1759)

|

Suite

d-moll - aus "Suites de Pièces

pour le clavecin", 2. Collection |

|

9' 19" |

A3 |

|

-

Allemande · Courante · Sarabande ·

Gigue |

|

|

|

| Johann Caspar Ferdinand

Fischer (um 1665-1746) |

Suite

VI D-dur - aus "Musicalisches

Blumen-Büschlein" |

|

12' 40" |

B1 |

|

-

Präludium · Allemande · Courante ·

Sarabande · Gigue · Bourée · Menuet |

|

|

|

| Johann Christoph Bach (1642-1703) |

Aria

mit 15 Variationen a-moll |

|

15' 50" |

B2 |

|

Long Playing 2 |

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian Bach (um

1685-1750) |

Präludium

und Fuge C-dur, BWV 846 |

|

4' 43" |

C1 |

|

Präludium

und Fuge B-dur, BWV 866 |

|

4' 52" |

C2 |

|

Capriccio

über die Abreise seines geliebten

Bruders, BWV 992 |

|

13' 40" |

C3 |

|

Französische

Suite G-dur, BWV 816 |

|

22' 32" |

D1 |

|

-

Allemande · Courante ·

Sarabande · Gavotte · Bourée

· Loure · Gigue |

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 3 |

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian Bach (um

1685-1750) |

Toccata

d-moll, BWV 913 *

|

|

13' 42" |

E1 |

|

-

(Allegro moderato) · (Presto) ·

Adagio · Allegro |

|

|

|

|

Toccata

G-dur, BWV 916 *

|

|

8' 04" |

E2 |

|

-

(Presto) · Adagio · Allegro |

|

|

|

|

Triosonate

Es-dur, BWV 525 **

|

|

13' 53" |

F1 |

|

-

Allegro |

2' 53" |

|

|

|

-

Adagio |

7' 02" |

|

|

|

-

Allegro |

3' 58" |

|

|

|

Triosonate

c-moll, BWV 526 **

|

|

10' 49" |

F2 |

|

-

Vivace |

3' 53" |

|

|

|

-

Largo |

3' 03" |

|

|

|

-

Allegro |

3' 53" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bradford

TRACEY *

|

Bradford

TRACEY

|

Rolf JUNGHANNS

|

Rolf

JUNGHANNS & Bradford TRACEY **

|

|

|

|

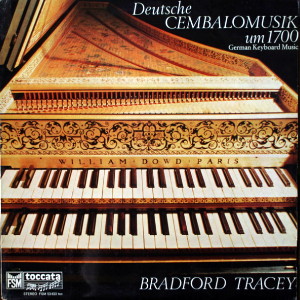

Buxtehude / Zachow / Händel

/ Fischer / J. C. Bach (Long Playing 1)

|

J. S. Bach (Long Playing 2)

|

J. S. Bach (Long Playing 3) |

| -

Cembalo nach Ruckers, Antwerpen um

1620, von William Dowd |

-

an zwei

Clavicord-Originalinstrumenten aus

der Sammlung Fritz Neumeyer, Bad

Krozingen |

-

Cembali nach Blanchet, Paris um

1730, von William Dowd, Paris

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Schlos

Bad Krozingen (Germania) - 1976 (Buxtehude,

Zachow, Handel, Fischer,

J.C. Bach)

Gobelinsaal,

Markgrafenschloss, Ansbach

(Germania) - luglio 1975

(J.S. Bach, long playing 2)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision

|

|

Paul

Dery |

|

|

Edizione LP |

|

TELEFUNKEN

- 6.35521 EK - (3 LP's - durata

55' 29", 45' 47" & 46' 28") -

(p) 1975/76/80 |

|

|

Originale LP

|

|

TOCCATA

- FSM 53 623 - (1 LP - durata

55' 29") - (p) 1976 -

Analogico (Buxtehude, Zachow,

Handel, Fischer, J.C. Bach)

TOCCATA - FSM 53 619 - (1 LP -

durata 45' 47") - (p) 1975 -

Analogico (J.S. Bach, long

playing 2)

TELEFUNKEN - 6.35521 EK - (3°

LP - durata 46' 58") - (p)

1980 - Analogico (J.S. Bach,

long playing 3)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

FSM

Adagio - FCD 91 619 - (1 CD -

durata 45' 47") - (c) 1991 -

AAD (J.S. Bach, long playing

2)

|

|

|

Note |

|

Production

by Toccata.

|

|

|

|

|

German

Keyboard Music

ca. 1700

While the

17th century saw

the development of

distinct national

keyboard styles in

both France and

Italy, a 17th

century German

keyboard style

defies definition.

We are immediately

presented with a

long and varied

list of composers

- each with his

own personal and

distinctive

approach to the

keyboard. There

were those more

travelled

composers, such as

Froberger, Kerll

and Muffat who

ventured to learn

the new styles

first-hand from

such masters as

Chambonnières and

Lully in France

and Frescobaldi in

Italy. But there

were those, who,

bound by duties at

court and church,

remained at home

and absorbed what

innovations came

their way -

incorporating both

the old and new

into their own

personal style.

Perhaps one of the

best examples of

such a 17th

century composer

is Dietrich

Buxtehude. While

his keyboard

suites are in

predominantly

French style, his

organ works are a

mixture of all

existing styles of

the day. The

Prelude and Fugue

in G minor, with

its contrasting

rhapsodie and

strict sections,

reminds us of a

Froberger or Rossi

toccatas, while

the playful

rhythmic

juxtapositions

echo Sweelinck,

John Bull and the

variation

techniques of

Elizabethan

England. Like the

Frescobaldi and

Froberger

toccatas, it lends

itself well to

performance on

both the organ and

the harpsichord.

Friedrich Wilhelm

Zachow, who has

been practically

forgotten as a

composer, is

remembered today

chiefly as

Handel's teacher.

Although most of

his keyboard works

have been lost,

his suite in B

minor, the only

existing suite, is

one of the

masterpieces in

the 17th century

keyboard

literature. That

Handel quoted the

theme from the

Fuga Finalis in

one of his

Concerti Grossi

shows the impact

it had on his

young pupil.

Handel’s Suite in

D minor - though

published in 1733

- can well be one

of the suites he

wrote while under

Zachow’s tuition

during those early

years in Halle.

Johann Caspar

Ferdinand Fischer,

composer to the

Markgraf of Baden,

was a devote

francophile. His

Pièces de

Clavecin, or

Musicalisches

Blumen-Büschlein,

published 1696,

contain a few

suites ordered

after Froberger,

but mostly Lullian

"ballet" suites

with an assortment

of gavottes,

bourrées, menuets,

passepieds and

rondeaus.

According to

Forkel, Fischer

was one of the

composers Johann

Sebastian Bach

studied during his

stay in Ohrdruf.

Indeed, Fischer’s

influence on Bach

is not to be

underestimated.

His Ariadne Musica

of 1717 served as

a model for Bach’s

Well Tempered

Clavier, while the

close link between

the prelude from

the D major suite

and Bach's B flat

prelude from the

WTC I is evident.

The recent

recovery of Johann

Christoph Bach’s

long lost Aria

with 15 Variations

presents us with

another major

composition which

directly

influenced Johann

Sebastian Bach.

Christoph Bach, a

cousin of Johann

Sebastian Bach’s

father Ambrosius,

is the most

significant member

of the Bach family

before Johann

Sebastian. Born in

Arnstadt, he

worked later as

organist in

Eisenach and

harpsichordist and

chamber musician

to the ducal

chapel. The close

parallels between

this profound work

and Johann

Sebastian Bach's

Aria variata alla

maniera italiana

proves Sebastian's

knew and studied

the work well.

Johann

Sebastian

Bach: Music

for Clavichord

and

Harpsichord

While the

harpsichord plays

a significant role

in the modern

interpretation of

Johann Sebastian

Bach's keyboard

works, the

clavichord remains

almost forgotten,

although it was as

widespread in the

17th and 18th

centuries as the

harpsichord. It

possesses a number

of advantages: it

is small, light,

easy to transport,

has a reliable and

simple mechanism

as well as a

pleasant tone

capable of the

finest of nuances.

It’s major

disadvantage is

its extremely

gentle tone which

makes an ensemble

performance, as

well as one before

a larger audience,

almost impossible.

We can probably

account this as

the main reason

for its slow

"rediscovery".

The most-quoted

verification for

the use of the

clavichord

originates from

the first Bach

biography by

Johann Nikolaus

Forkel, 1802:

"He

(Johann

Sebastian

Bach) liked to

play on the

clavichord

best of all

... He thought

the clavichord

to be the best

instrument to

study by as

well as for

private

musical

entertainment.

He found it

most

appropriate

for the

interpretation

of his finest

musical ideas,

and didn't

believe it

possible to

produce such a

manifold

variety of

shading at the

harpsichord or

pianoforte as

at this quiet

but pliant

instrument."

Forkel

supports himself

with reports from

Johann Sebastian

Bach’s sons, Carl

Philipp Emanuel

and Wilhelm

Friedemann, both

of whom were

famous clavichord

players at a time

when the

clavichord was,

without a doubt,

the most popular

keyboard

instrument. For

this reason is

Johann Sebastian

Bach's preference

for the clavichord

not clearly

proven, but we can

nevertheless be

sure that Bach

played the

clavichord and

valued it highly.

Johann Sebastian

Bach probably

composed the seven

toccatas for

harpsichord in

Weimar between

1708 and 1717.

During this period

Bach had renewed

his interest in

Italian music and

wrote his

transcriptions of

string concertos

by Vivaldi and

other composers.

Thus, in the G

major toccata

certain powerfully

descending triads

in the first

movement resemble

"performance modes

which more

frequently occur

in the piano

transcriptions of

Vivaldi" (Spitta).

Furthermore, the

first bars of the

tutti concept

recall the second

allegro movement

in Vivaldi’s B

minor concerto.

Altogether the G

major toccata

features the three

movement structure

of the typical

concerto grosso,

and even in the

opening allegro

the characteristic

alternation

between solo and

tutti.

The trio sonata

with two upper

parts and

thoroughbass (bass

part as well as

fill-in chords)

was the most

assiduously

cultivated genre

of chamber music

in the 18th

century. The upper

parts were played

on two violins,

two flutes, two

oboes or also in

mixed

combinations, with

the bass

instrument cello,

viola da gamba or

bassoon, and

harpsichord, lute

or choir organ

providing

harmonious

support. In this

way four

performers were

involved in the

rendering of a

trio sonata.

In addition, it

was also customary

for two performers

to play trios,

with only one

melody instrument

and obbligato

harpsichord. The

latter was

responsible for

the second melody

part as well as

the bass part.

That these

different manners

of performance

existed side by

side with each

other is shown by

the example of the

trio sonata in G

major by Johann

Sebastian Bach

which is available

in two versions:

in one case for

two transverse

flutes with

thoroughbass, and

the other for

viola da gamba

with obbligato

harpsichord. If

the trio sonata

were then

entrusted

completely to the

keyboard

instrument, other

possibilities of

performing it

again resulted.

The three-part

element could be

represented either

by only one of the

players on one

instrument with

two manuals and

pedal (organ,

pedal harpsichord

or also pedal

clavichord), or

the music was

played on two

harpsichords,

spinets or

clavichords in the

manner as

described by

Francois Couperin

in the foreword to

his grand trio

"L'Apothéose de

Lulli" (1725):

"This

trio, just

like the

'Apothéose de

Corelli', and

the whole

collection of

trios which I

intend to

publish next

july, can just

as well be

played on two

clavecins as

on all other

instruments.

In my family,

and with my

pupils, I

perform it

with a great

deal of

success with

the upper part

of the bass

being played

on the one

clavecin

(harpsichord)

and the second

on the other,

with the same

bass in

harmony. Now

the situation

here is that

two copies are

needed for

this instead

of one, as

well as two

clavecins. For

the rest,

however, I

find that it

is often

easier to

bring these

two

instruments

together than

four people

who make music

... The

performance

will result in

a not less

pleasant

impression,

especially

since the

clavecin in

its way has a

brilliance and

clarity which

one can

scarcely find

with other

instruments."

Two of the

six so-called

organ trio sonatas

by Johann

Sebastian Bach are

played here in

accordance with

Couperin’s

directions. From

the intermediate

position between

organ and chamber

style, Philipp

Spitta concluded

that these unique

masterpieces,

which Bach wrote

as practice pieces

for the organist

training of his

eldest son Wilhelm

Friedemann, were

intended for the

pedal harpsichord

or pedal

clavichord.

|

|

|