|

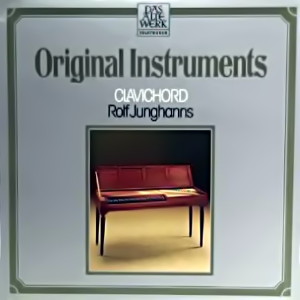

1 LP -

Telefunken 6.42073 AP (p) 1979

|

|

| ORIGINALINSTRUMENTE - Clavichord |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Christoph

Friedrich Bach (1732-1795) |

Sonatina

a-moll (aus: Musikalische

Nebenstunden, 1787/88)

|

|

13' 12" |

|

|

-

Allegretto |

4' 30" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Siciliano: Andante |

3' 17" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Rondo: Allegretto |

5' 25" |

|

A3 |

| Carl Philipp

Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) |

Sonata

V F-dur, Wq 55 Nr. 5 (aus: 6

Klavier-Sonaten für Kenner und

Liebhaber, 1. Sammlung, 1979) |

|

9' 01" |

|

|

-

Allegro |

4' 30" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Adagio maestoso |

2' 34" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Allegretto |

1' 57" |

|

A6 |

| Carl

Philipp Emanuel Bach |

Sonata

III h-moll, Wq 55 Nr. 3 (aus: 6

Klavier-Sonaten für Kenner

und Liebhaber, 1. Sammlung,

1979)

|

|

8' 09" |

|

|

-

Allegretto |

4' 12" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Andante |

1' 24" |

|

B2 |

|

-

Cantabile |

2' 33" |

|

B3 |

Wilhelm

Friedemann Bach (1710-1784)

|

Sonata

B-dur |

|

12' 35" |

|

|

-

Un poco allegro |

5' 05" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Grazioso |

2' 33" |

|

B5 |

|

-

Allegro di molto |

4' 57" |

|

B6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Rolf JUNGHANNS,

Clavichord (von Carl Schmahl,

Regensburg, Ende 18. Jahrhundert,

aus der Sammlung historischer

Tasteninstrumente Fritz Neumeyer,

Schloß Bad Krozingen) |

|

5

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Schloß

Bad Krozingen (Germania) - 1979

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording

Supervision

|

|

-

|

|

|

Edizione LP |

|

TELEFUNKEN

- 6.42073 AP - (1 LP - durata 42'

57") - (p) 1979 - Analogico |

|

|

Originale LP

|

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

-

|

|

|

Note |

|

Produced

by Toccata

|

|

|

|

|

The origins

of the clavichord

go back to ancient

times. This

instrument was

developed from the

monochord, a

resonance box with

strings, on which

the regular

relation of string

length to the

pitch of the tone

could be studied

by graduating the

string. Towards

the end of the

Middle Ages, it

appears as a

musical instrument

as the monochord

was combined with

the keyboard of an

organ. Small flat

brass blades, the

tangents, at the

end of the key

levers strike the

strings at

different points

and cause them to

vibrate when the

key is depressed.

The clavichord was

regarded as the

ideal instrument

“for study or in

general for

private musical

entertainment.”

Despite its

unusually low

timbre, it was,

for several

centuries, just as

widespread as the

harpsichord, as it

has a number of

superior

qualities: it is

small, light,

wieldy, is

mechanically

reliable and

simple which,

however, demands a

sensitive command;

it has a highly

agreeable sound

due to the great

variety of

overtones.

The era of

sentimentality

which followed the

change of style

towards the middle

of the 18th

century was the

golden age of the

clavichord. At

this time, it was

praised especially

for its dynamic

power of

expression and its

sensitive timbre

as the “solitary,

melancholic,

unspeakably

delightful

instrument ... He

who has an

aversion to

reveliy, fury and

tumult and whose

heart often

delights in sweet

sensations, will

pass by the

harpsichord and

the pianoforte and

choose the

clavichord”

(Christian

Friedrich Daniel

Schubart, 1785).

Throughout this

period, the

harpsichord

remained the

preferred concert

instrument,

whereas at the

time the

pianoforte had

neither the

richness of tone

of the harpsichord

nor the expressive

qualities of the

clavichord. Only

decades later

would it supplant

both of them.

Until then the

clavichord

remained the most

widespread

keyboard

instrument and was

called simply

“clavier.” It was

of great

importance in the

particularly

active musical

life of the German

burgher.

The most famous

performers on this

instrument were

the sons of Johann

Sebastian Bach,

especially Carl

Philipp Emanuel

Bach, whose

improvisations on

the clavichord won

the admiration of

his

contemporaries.

Although their

compositions for

clavichord were

also played on

harpsichord or

pianoforte, they

only attained

their singular

beauty when played

on the clavichord

with its

“responsiveness to

the stiriings of

the soul.”

The lack of

richness of sound

of this otherwise

so perfected

instrument has

often been

regretted.

Nevertheless its

particular charm

lies precisely in

the clavichord’s

faint whisper,

which demands the

listener’s utmost

concentration.

Therefore the tone

of the clavichord

should by no means

be amplified in

reproduction. Only

when the listener

plays the

recording so low

that he must

concentrate and

listen in total

silence, will he

understand the

exuberant praise

of the “mild

clavier.”

Rolf

Junghanns

(English

translation by

Elisabeth

Geiger)

|

|

|