|

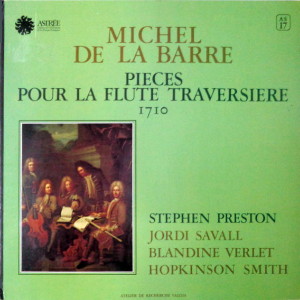

1 LP -

Telefunken 6.42325 AP (p) 1978

|

|

| 1 LP -

Astrée AS 17 (p) 1978 |

|

| 1 CD -

Astrée E 7786 (c) 1991 |

|

ORIGINALINSTRUMENTE -

Traverflöte

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Michel de la Barre

(um 1675-1743) |

Suite

Nr. 2 G-dur - aus Livre I |

|

16' 17" |

|

| Pièces

pour la flûte traversière, 1710 |

-

Prèlude |

2' 55" |

|

A1 |

|

-

Allemande. La Signora |

2' 21" |

|

A2 |

|

-

Gigue. La Cadette |

1' 00" |

|

A3 |

|

-

Sarabande. L'Ainée |

3' 55" |

|

A4 |

|

-

Allemande. La Landais |

1' 54" |

|

A5 |

|

-

Rondeau. Le Ninon |

1' 24" |

|

A6 |

|

-

Gavotte. La Therese; Double |

1' 38" |

|

A7 |

|

-

Rondeau. Le Étourdi |

2' 25" |

|

A8 |

|

-

Gigue. L'Ecossoise |

1' 45" |

|

A9 |

|

Suite

Nr. 5 d-moll - aus Livre I |

|

14' 35" |

|

|

-

Prelude |

3' 35" |

|

B1 |

|

-

Allemande. La Mariane |

3' 03" |

|

B2 |

|

-

Rondeau. L'Affligè |

2' 52" |

|

B3 |

|

-

Allemande. La Villequiere |

2' 59" |

|

B4 |

|

-

Gavotte. La Bagatelle |

0' 47" |

|

B5 |

|

-

Rondeau. Le Provençal |

1' 19" |

|

B6 |

|

Suite

Nr. 9 G-dur - aus Livre II |

|

9' 34" |

|

|

-

Sonate. L'inconnu · Vivement

· (Lentement) |

3' 50" |

|

B7 |

|

-

Chaconne |

5' 44" |

|

B8 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stephen PRESTON,

Traverflöte (Andreas Glatt, Kopie

nach Hotteterre, Anfang 18. Jh.) |

Jordi Savall,

Viola da gamba (siebensaitig,

unbekannter französischer Erbauer,

Ende 17. Jh.) |

|

|

Blandine Verlet,

Cembalo (Pierre Bellot, 1729;

Muée de l'Archevêché, Chartres) |

|

|

Hopkinson Smith,

Theorbe (vierzehnchörig, Mathias

Durvie, nach Mateo Sellas, Venedig

1637) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Saint-Lambert-des-Bois,

Yvelines (Francia) - aprile 1977 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer |

|

Michel

Bernstein

|

|

|

Recording

Supervision

|

|

Dr.

Thomas Gallia, Milan |

|

|

Edizione LP |

|

TELEFUNKEN

- 6.42325 AP - (1 LP - durata 40'

26") - (p) 1978 - Analogico |

|

|

Originale LP

|

|

ASTRÉE

- AS 17 - (1 LP - durata 40' 26")

- (p) 1978 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

ASTRÉE - E 7786 -

(1 CD - durata 40' 26") - (c)

1991 - AAD |

|

|

Note |

|

Produced

by Astrée |

|

|

|

|

The 17th

century brought

important changes

in the

construction and

mode of playing of

many musical

instruments, among

them the

transverse flute.

Throughout the

century the term

flute continued to

refer to the

recorder. But

probably after

1650 - the

beginnings are

obscure - work

began in Paris on

a new flute which

was intended to

have a greater

tonal range. In

place of what

until then had

been a cylindrical

tube, the

instrument was

given a conversely

conical bore; that

is to say, the

tube narrowed down

from the

embouchure to the

end; the

finger-holes were

designed according

to the reach of

the fingers. The

instruments were

made of box-tree,

ivory, maple,

peartree, ebony or

rosewood, and

until the

beginning of the

18th century

possessed a valve.

Jacques

Hotteterre, the

flute virtuoso and

instrument maker,

called “Le

Romain”, in his

fundamental work

on performance and

construction of

the instrument

“Principes de la,

flûte traversière”

(Paris, 1707) was

the first to

suggest an

arrangement of the

finger-holes based

upon the acoustic

principles of mean

tone tuning, the

.most important

precursor of

well-tempered

tuning.

Hotteterre’s

directions on

construction and

performance

disposed of the

problems existing

until then

resulting from

differing finger

reaches, and

construction of

the instrument was

then determined by

the finger reach.

Furthermore

Hotteterre’s

introduction made

it possible to

expand the tonal

range by higher

octaves. In view

of the fact that

it is based upon

the acoustic

principle of mean

tone intonation

and consequently

upon pure major

thirds, they are

not the same as

the enharmonic

tones on the

present-day piano:

according to

Hotteterre’s

system, the A

lowered to A-flat

sounds higher than

the G raised to

G-sharp. Nowadays,

instruments with

varying tone

rendering play the

G-sharp higher, as

a leading note to

A; As far as music

of that time was

concerned,

however, this

solution involved

adjustment to the

musical practice

of the singers and

violinists. An

instrument with

qualities of this

kind was played in

the present

recording. From a

language point of

view the

transverse flute

was distinguished

from the recorder,

generally

described as the

flute, by way of

the names flûte

traversière, flûte

d’Allemand or

simply Traversa.

Of the instruments

in various

registers, only

the descant

register was

really able to

hold its own,

while the others,

such as flûte

d’amour or

Traversa bassa

remained special

forms.

Initially the

instrument was

played only by

aristocratic

personages in

France; but due to

the predilection

of Frederick the

Great for the

instrument, it

became the most

widely distributed

music lover’s

instrument of the

18th century.

Johann Joachim

Quantz

(1690-1771), flute

tutor to the

mighty Prussian

monarch, reported

on his first

lessons in 1719 in

Dresden: “At that

time there were

not many pieces

written

specifically for

the flute. For the

greater part one

made do with oboe

and violin pieces

which each person

utilised as best

he could”. The

number of

concertos dating

back to the 18th

century, however,

has been estimated

at about 6,000.

With the “Pièces

pour la flûte

traversière” by

Michel de la Barre

(ca. 1675-1743)

the first works

for the instrument

appeared in print.

As flautist, de la

Barre performed as

a chamber musician

at the court of

the Sun King; as

composer, he

succeeded in

deriving typical

phrases from his

instrument. In

addition to two

operas, he wrote

compositions for

one and two

flutes, as well as

trios for flute,

violin and oboe.

Gerhard

Schuhmacher

(English

translation by

Frederick A.

Bishop)

|

|

|