|

|

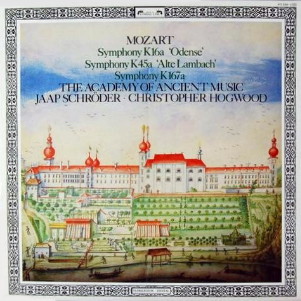

1 LP -

417 234-1 - (p) 1986

|

|

| 1 CD -

417 234-2 - (p) 1986 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| Wolfgang Amadeus

Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony in A

Minor "Odense", K. 16a |

|

13'

34"

|

|

| -

[Allegro moderato ∑ Andantino ∑

Rondo: Allegro moderato] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in G Major "Alte Lambach", K. 45a |

|

14' 23" |

|

| -

[Allegro ∑ Andante ∑ Menuetto &

Trio ∑ Finale] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 185 / K. 167a |

|

28' 05" |

|

| -

[Allegro assai ∑ Andante grazioso ∑

Menuetto & Trio ∑ Adagio-Allegro

assai] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap SchrŲder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.

Barnabas' Church, London (United

Kingdom):

- gennaio 1984 (K. 167s)

Walthamstow Assembly Hall, London

(United Kingdom):

- agosto 1985 (K. 16a, 45a)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Morten

Winding / John Dunkerley |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 417 234-1 (1 LP) - durata

56' 02" - (p) 1986 - Digitale |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 417 234-2 (1 CD) - durata

56' 02" - (p) 1986 - ADD |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

in G major, K.45a

(A221)

At the beginning of January

1769 the Mozart family

stopped at the

Benedictine monastery at

Lambach, which, like

many monasteries,

provided rooms and meals

for travellers, and

maintained an orchestra

andchoir for worship and

entertainment. It

was a convenient

way-station for the

Mozarts on journeys

between Salzburg and

Vienna, and the abbot

was a family friend.

This visit, not

mentioned in the

Mozarts' correspondence

or diaries, is known

solely from inscriptions

on two musical

manuscripts. Both are

sets of parts for

symphonies in G major,

one inscribed Sinfonia

/ a / 2 Violini / 2

Oboe / 2 Corni / Viola

/ e / Basso. / Del

Sig:re

Wolfgango

/ Mozart. / Dono

Authoris / 4ta Jan:

769 and the other

bearing an identical

inscription with

'Leopoldo' in place of 'Wolfgango'.

Alfred Einstein, in

assigning Wolfgangís

work the number 45a in

the 3rd edition of the KŲchel

Catalogue (1937),

guessed that it was

composed in 1768 while

the 12-year-old composer

was in Vienna.

Subsequently however, it

was discovered that the

Lambach manuscripts were

the work of a Salzburg

copyist and must have

been copied there in

1767. In recent years it

was proposed, and widely

accepted, that the two works

had carelessly been

interchanged by a

librarian at Lambach.

(For details of this

proposal and for

Leopold's Lambach

symphony see Volume 7 of

the Mozart symphonies on

D173D3).

The confusion was

resolved in February

1982 when the Munich

Staatsbibliothek

announced the

rediscovery of the

original parts for K.45a,

comprising first and

second violin in the

hand of a copyist, 'basso'

part in the hand of

Mozartís sister Nannerl,

and the rest in

Leopoldís hand. The

title page in Leopoldís

hand is virtually

identical to that on the

Lambach copy but ends 'ŗ la

Haye 1766'.

K.45a

therefore forms a

pendant to the Symphony

in B flat, K.22, also

composed at the Hague,

where the Mozarts were

enthusiastically

received (see Volume 1

on D167D3). These two

symphonies may have been

written (with the Galimathias

musicum,

K.32) for the

investiture of Prince

William of Orange. In

that case they were what

Leopold referred to in a

letter when he wrote

that Wolfgang 'had

to compose something for

the Prince's concert' of

11 March 1766.

Comparison of the Hague

and Lambach manuscripts

reveals that K.45a was

revised in Salzburg in

1767: no bars of music

were added or removed

and no new ideas

introduced; rather,

dozens of details were

altered, especially in

the inner parts. The

revision of K.45a

suggests its performance

in Salzburg between

December 1766 and

October 1767, after

which the work was taken

on tour to Vienna.

The first movement of K.45a

begins with the melody

in the bass and tremolo

in the violins, a

texture that Mozart

usually reserved for

near the ends of

expositions and of

recapitulations. In a

number of his early

symphonies the incipits

of the first and last

movements have similar

melodic contours; in

K.45a however, the

second or lyrical

subjects of those

movements are so

related. The 3/8 finale

is so much of a piece

with the 3/8 finales of

the other early

symphonies, K.16, 19,

19a and 22, that all may

be said to belong to the

same general conception.

As for the Andante,

the Lambach version is

the first of Mozartís

symphonies to use a

favourite orchestral

texture found in the

andantes of eight later

symphonies: the wind are

silent or reduced,

violins muted, and

cellos and basses play

pizzicato. But mutes and

pizzicato are not

indicated in the Hague

version, and the

occasional slur in the

bassline shows that

pizzicato was not

intended by the

ten-year-old composer.

This is the first

recording of the

original version of K.45a.

Symphony in Aminor,

K.16a (A220)

In February 1983

newspapers in many

countries reported the

rediscovery of a lost

Mozart symphony The

facts as they later

emerged were these: the

librarian of the

municipal orchestra in

Odense, Denmark, was

examining a collection

of music which at the

end of the eighteenth

century had belonged to

the local Collegium

Musicum. Among several

late-eighteenth-century

symphonies, the

librarian found the lost

Symphony in A minor, K.6a.

According to an

annotation on its title

page, K.16a came into

the possession of the

Collegium no later than

1793, but this set of

parts was not new then

for the watermark in the

paper used reads '1779'.

None of the hands in the

Odense parts belongs to

a copyist associated

with the Mozarts or

their circle.

How

did it happen that a

work previously unknown

can have had a KŲchel

number waiting for it?

The answer is that when,

from around 1799, the

Leipzig publishers

Breitkopf & Hšrtel

attempted to collect

Mozartís works from his

sister, his widow and

musicians, copyists and

publishers all over

Germany and Austria,

they were sent this

symphony. It was duly

listed in their

manuscript catalogue of

Mozartís works, with an

incipit of four bars of

the first violin part

and the workís source: 'Westphal'.

(This was the Hamburg

music dealer Johann

Christoph Westphal.) By

KŲchel's

time, this manuscript

had vanished, and he

placed the work in his

appendix for lost works

as Anhang 220. In

the 3rd edition of the KŲchel

Catalogue, Einstein

speculatively inserted

such incipits of lost

works into the

chronological sequence

of works. Solely on the

evidence of the incipit,

he guessed that the

workís style was

Mozartís earliest and

closely related to that

of J.C.Bach

and C.F. Abel,

whose symphonies Mozart

studied in London in

1764-65 (see Volume 1).

He therefore arbitrarily

assigned it a number

immediately following

Mozartís earliest

surviving symphony K.16,

of 1764.

With the music in hand,

we may guess that the

work is later. But even

if it may be

stylistically closer to

Mozartís symphonies of

the later 1760s and

early 1770s, without an

authentic source it can

be neither firmly

attributed nor precisely

dated. Indeed, many

things about K.16a

are stylistically unlike

any work of Mozartís.

The opening Allegro

moderato presents

two contrasting motives

- a descending broken

chord, sforzando

and unisono, and

a more lyrical idea, piano

- organized into

three-bar phrases and

providing the material

for the first thirty

bars, which end (as

expected) in C major.

The second theme group

begins with a new idea,

and at bar forty-eight

the exposition ends

(astonishingly) in F

major, with a closing

theme derived from the

lyrical idea of the

opening. There is no

repeat. The development

section begins with the

expositionís closing

theme and then offers a

modulatory section

leading to an incomplete

recapitulation and

closing ritornello.

The second movement, a

short sonata form, opens

with a songful theme

that, like a few of

Mozartís other early

symphony andantes, is

reminiscent of 'Che farÚ

senza Euridice'

from Gluck's Orfeo.

The finale, like those

of many of Mozartís

early symphonies, is a

rondo. Its refrain has

some of the 'exotic'

flavour that Mozart and

his contemporaries

called 'Turkish',

which was apparently an

imitation of music of

Hungarian peasants who

themselves parodied what

they took to be Turkish

music.

Symphony in D major,

K.167a (K.185)

Orchestral serenades and

symphonies had different

functions. Serenades

provided entertainment

for such celebrations as

birthdays, promotions,

ends of school terms,

investitures, and the

like; whereas symphonies

were the briefer

prefaces to more formal

occasions: plays,

operas, oratorios and

concerts. As Mozartís

Salzburg serenades were

made up of a march,

minuets, concerto

movements, and symphony

movements, they could

easily be raided for

suitable movements when

symphonies were needed.

Of Mozartís six

orchestral serenades,

symphony versions

survive for five of

them. In the

sixth and present

instance, no symphony

version

survives, but there must

have been one as the

work was listed as a

symphony in the already

mentioned Breitkopf

& Hšrtel

manuscript catalogue.

The date on the

autograph of K.167a

('August 1773'?) was

tampered with and is

nearly illegible. If,

as is generally

believed, the work is

'the Finalmusik

for Antretter' mentioned

in the Mozarts'

correspondence, then it

was written for the end

of the Salzburg

University term,

celebrated annually in

early August. In August

1773 the Mozartís friend

Judas

Thaddšus

Antretter was completing

his fourth year at the

University. The symphony

version was presumably

made sometime shortly

thereafter.

The first movement, Allegro

assai in common

time, begins with a

theme in the bass, which

returns at the beginning

of the recapitulation

and, in unison and in

contrary motion, at the

ends of the exposition

and recapitulation. As

in a number of Mozartís

other D major movements,

brilliance and pomp is

contrasted with lighter

and even comical ideas,

while lyricism is

conspicuously avoided.

In characteristically

expansive serenade

spirit, this sonata-form

movement has both

sections repeated and a

full coda. Yet despite

the striving for length,

the development section

is slight and the

overall spirit closer to

an Italian opera

overture than to an

Austrian concert

symphony.

The andante grazioso

which follows (the tempo

indication was written

by Leopold, not

Wolfgang) is in A major

and the customary 2/4.

Trumpets and drums fall

silent, a pair of flutes

replaces the oboes of

the other movements, and

the mood turns lyrical.

After an imitative

opening with the wind

prominent, the violins

dominate the rest of the

movement in a homophonic

texture of a binary form

with both halves

repeated and a coda.

In the Minuet the full

band returns and the

movement opens with a

fanfare used by Mozart

in a number of other

pieces. Here, the

character seems stagey

and perhaps even

burlesque. The first

Trio calls for upper

strings alone, with a

mock-pathetic violin

solo in D minor

providing a jarring

contrast to the

hurly-burly of the

Minuet proper. The

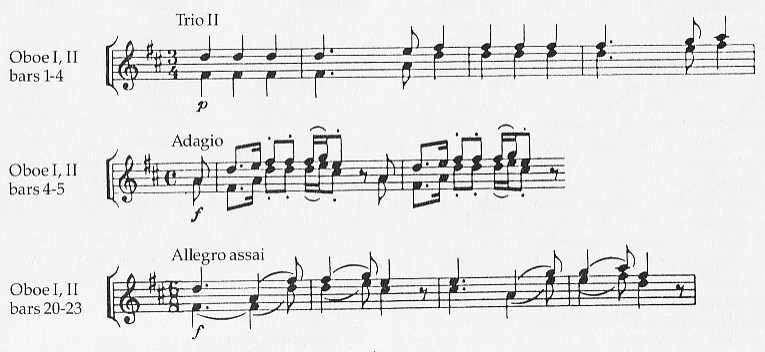

second Trio, in D major,

features the wind in an

attractive al fresco

style.

An eleven-bar Adagio

in which stern unisons,

noble dotted rhythms,

and touches of

chromaticism momentarily

thrust us into the world

of tragic opera opens

the finale. But Mozart

is only teasing, for

this solemn introduction

leads to a spirited 6/8

jig (Allegro assai,

in Leopoldís hand),

rounding off the

symphony in high

spirits. This jig is a

largescale sonata-form

movement with a fine

development section and

full coda in which, as a

final surprise, Mozart

inserted a so-called 'Mannheim

crescendo'. The D major

Trio, the Adagio

introduction, and the

principal theme of the

jig are linked by

transformations of a

common wind motive:

©

1986

Neal Zaslaw

|

|

|