|

|

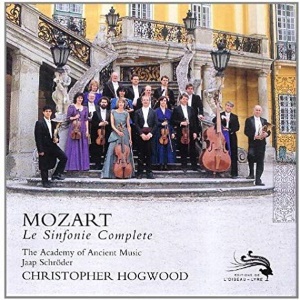

3 LP's

- D173D3 - (p) 1982

|

|

| 3 CD's -

421 135-2 - (c) 1987 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| The Symphonies

- Vol. 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

58' 27" |

|

| Symphony No. 6 in

F Major, K. 43 |

17' 00" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante · Menuetto &

Trio · Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 7 in D Major, K. 45 |

12' 12" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante · Menuetto &

Trio · Finale] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 43 in F Major, K. 76 / K. 42a |

15' 05" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro maestoso · Andante ·

Menuetto & Trio · Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 55 in B flat Major, K. 45b /

Anh. 214 |

14' 10" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante · Menuetto &

Trio · Allegro] |

|

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

57' 01" |

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 51 / K. 46a |

6' 19" |

|

|

| - [Molto allegro ·

Andante · Molto allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in G Major, "Neue Lambacher" |

22' 21" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante un poco

allegretto · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

in B flat Major, K. 74g / anh. 216 |

14' 53" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro molto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 37 in G Major, K. 425a / K.

444 / Anh. A53 (mov. II & III

di Michael Haydn) |

13' 28" |

|

|

| - [Adagio

maestoso-Allegro con spirito ·

Andante sostenuto · Finale

(Allegro molto)] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

50' 44" |

|

| Symphony

No. 8 in D Major, K. 48 |

15' 18" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 40 (2nd version) in G Minor,

K. 550 |

|

|

|

| - [Molto allegro] |

6' 52" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - [Andante ·

Menuetto & Trio · Allegro

assai] |

28' 34" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap Schröder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

|

|

| Violins

|

Jaap

Schröder (Antonio Stradivarius

1709 & Jakob Stainer 1665 ) - Catherine

Mackintosh (Rowland Ross 1978

[Amati] & Ian Boumeester, Amsterdam

1669) - Simon Standage

(Rogeri, Brescia 1699) - Monica

Huggett (Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Elizabeth Wilcock

(Grancino, Cremona 1652) - Roy

Goodman

(Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius 1688])

- David Woodcock (Anon., circa

1775) - Joan

Brickley

(Mittewald,

circa 1780) -

Alison Bury

(Anon.,

England, circa

1730) - Judith

Falkus

(Eberle,

Prague 1733) -

Christopher

Hirons

(Duke, circa

1775) - John

Holloway

(Sebastian

Kloz 1750

& Mariani

1650) - Polly

Waterfield

( Rowland Ross

1979 [Amati])

- Micaela

Comberti

(Anon.,

England circa

1740) - Miles

Golding

(Anon.,

Austria, circa

1780 &

Roze, Orleans

1756 &

Betts School,

circa 1800) -

Kay Usher

(Anon.,

England, circa

1750) - Julie Miller (Anon.,

France, circa

1745 &

Rowland Ross

1979 [Amati])

- Susan

Carpenter-Jacobs

(Franco Giraud 1978

[Amati] &

Rowland Ross 1979

[Amati]) - Robin Stowell (David

Hopf, circa

1780) - Richard

Walz

(David Rubio

1977

[Stradivarius])

- Judith Garside (Anon.

France, circa

1730 &

Joseph Hill

(?), London

1766) - Rachel

Isserlis

(John Johnson

1759) - Robert

Hope Simpson

(Samuel

Collier, circa

1740) - Catherine

Weiss

(Rowland Ross

1977

[Stradivarius])

- Jennifer

Helsham

(Alan Bevitt

1979

[Stradivarius])

- Jane

Debenham

(Anon. German,

18th century)

- Roy

Howat

(Henry

Rawlins,

London Bridge

1775) - Christel

Wiehe

(John Johnson,

London 1759) -

Roy Mowatt

(Rowland Ross

1979

[Stradivarius])

- Roderick

Skeaping

(Rowland Ross

1976 [Amati])

- Eleanor

Sloan

(German(?),

circa 1760) -

June Baines

(Nicholas

Amati 1681) -

Stuart

Deeks

(Saxon, circa

1770) - Graham

Cracknell

(Anon. England

1780 &

Richard Duke

1787)

|

|

|

|

|

| Violas |

Jan Schlapp

(Joseph Hill 1770 & Rowland Ross 1980

[Stradivarius]) - Trevor Jones

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Katherine

Hart (Charles and Samuel Thompson

1750) - Colin Kitching (Rowland Ross

1978 [Stradivarius]) - Nicola Cleminson

(McDonnel, Ireland, circa 1760) - Philip

Wilby (Carrass Topham 1974 [Gasparo da

Salo]) - Annette Isserlis (Ian

Clarke 1980 [Guarnieri]) - Simon

Rowland-Jones (Anon. England, circa

1810) - Judith Garside (Hill School,

England 1766) |

|

|

|

|

| Violoncellos |

Anthony Pleeth

(David Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Richard

Webb (David Rubio 1975 [Januarius

Gagliano 1748]) - Mark Cuadle (Anon.

England, circa 1700 / David Rubio 1980 [D.

Montagnana 1720]) - Juliet Lehwalder

(Jacob Haynes 1745) - Susan Sheppard

(Peter Walmsley 1740 & Steiner School,

circa 1700) - Timothy Mason (Rowland

Ross 1979 [Stradivarius]) |

|

|

|

|

| Double

Basses

|

Barry

Guy (The Tarisio, Gasparo da

Salo 1560) - Peter McCarthy

(David Techler, circa 1725 &

Anon. England, circa 1770) - Keith

Marjoram (Anon., Italy c.1560)

- Keith Marjoram (Anon.

Italy, circa 1560) |

|

|

|

|

Flutes

|

Stephen

Preston (Anon. France, circa

1790 & Monzani c. 1800) - Nicholas

McGegan (George Astor, circa

1760) - Lisa Beznosiuk

(Goulding, London, circa 1805) - Guy

Williams (Monzani, circa 1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Oboes

|

Stanley

King (Rudolf Tutz 1978

[Grundmann]) - Clare Shanks

(W. Milhouse, circa 1760) - Sophia

McKenna (W. Milhouse, circa

1760) - David Reichenberg

(Harry Vas Dias 1978 [Grassi]) - Robin

Canter (Kusder, circa 1780

& H. Grenser c. 1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Clarinets |

Keith

Puddy (Moussetter, Paris

c.1790) - Lesley Schatzberger

(Metzler, London c.1812) |

|

|

|

|

Bassoons

|

Jeremy

Ward (Porthaus, Paris, circa

1780) - Felix Warnock

(Savary jeune 1820) - Alastair

Mitchell (W. Milhouse &

Clair Godfroy c. 1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Horns

|

William

Prince (Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Keith Maries (Anon.

Germany (?) circa 1785 &

Courtois neveu, circa 1800) - Christian

Rutherford (Kelhermann, Paris

1810 & Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Roderick Shaw

(Raoux, circa 1830) - John

Humphries (Halari, circa 1825)

- Patrick Garvey (Leopold

Uhlmann, circa 1810) - Colin

Horton (Courtois neveau c.

1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Trumpets

|

Michael

Laird (Laird 1977, German) - Iaan

Wilson (Laird 1977, German) -

Stephen Keavy (Keavy 1979,

German) - David Staff (Staff

1979, English 18th century) |

|

|

|

|

| Timpani |

David

Corkhill (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1810) - Charles Fullbrook

(Hawkes & Son, circa 1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Harpsichord

|

Christopher

Hogwood, Nicholas McGegan, David

Roblou (Thomas Culliford,

London 1782 & Rainer Schutze

1968 & Jacobus Kirckman 1766) |

|

|

|

|

| Fortepiano |

Christopher

Hogwood (Adlam Burnett 1976

[Mathaeus Heilmann c. 1785]) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kingsway

Hall, London (United Kingdom):

- novembre 1979 (K. 74g)

- settembre 1980 (K. 444)

- marzo 1982 (K. 550)

St. Jude's Hampstead Garden

Suburb, London (United Kingdom):

- maggio 1980 (K. 43, 45, 76, 45b,

51, "Neue Lambacher", 48)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Morten

Winding & Peter Wadland /

Simon Eadon & John Dunkerley |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - D173D3 (3 LP's) - durata

58' 27" | 57' 01" | 50' 44" - (p)

1982 - Analogico/Digitale (K. 550)

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 421 135-2 (3 CD's) - durata

60' 14" | 70' 18" | 64' 06" - (c)

1987 - ADD/DDD (K. 550) |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

L'Edizione

in 3 CD's (421 135-2) è

diversamente miscelata rispetto

all'originale pubblicazione in LP:

contiene infatti anche le Sinfonie

K. 16a e K. 45a).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

and the symphonic

traditions of his

time by Neal

Zaslaw

Vienna's

Orchestras

Perhaps the most important

turning point in Mozart's

life came at the age of

twenty-five, when he

already had to his credit

a corpus of music that

many a lesser talent would

gladly have accepted as

the fruits of a lifetime.

He decided to break with

his father and the

Archbishop of Salzburg,

and to remain in Vienna as

a free-lance

teacher, performer and

composer - a decision

which had far-reaching

implications for his music

and, hence, for the

evolution of the Viennese

classical style as a

whole. We have already

offered ample

documentation, in the

programme notes for

volumes 2-5 of this

series, of Mozart’s

disaffection towards

Salzburg. TheArchbishop

was stingy

and insufficiently

appreciative. Leopold

Mozart was continually

looking over his son's

shoulder and passing

judgement. Musical life

was circumscribed

and tastes conservative in

Salzburg, and Mozart’s

opportunities to show what

he could do in his

favourite genres - piano

concerto and opera - were

extremely limited. He

joyously described Vienna

to his father as 'keyboard

land'

(which it was); he might

with equal justification

have called it 'orchestra

land'.

Charles Burney was only

one of many visitors to

Vienna who commented upon

the excellence of the

orchestral playing there.

During his 1772 visit

he attended performances

at the two principal

theatres and gave this

expert testimony:

'The orchestra [at the

German theatre] has a

numerous band, and the

pieces which were played

for the overture and act

tunes, were very well

performed, and had an

admirable effect; they

were composed by Haydn,

Hofman[n], and Vanhall.

The orchestra here [at the

French theatre] was fully

as striking as that of the

other theatre, and the

pieces played were

admirable. They seemed so

full of invention, that it

seemed to be music of some

other world, insomuch,

that hardly a passage in

this was to be traced; and

yet all was natural, and

equally free from the

stiffness of labour, and

the pedantry of hard

study. Whose

music it was I could not

learn; but both the

composition and

performance, gave me

exquisite pleasure.'

Even if testimony such as

Burney’ s had not come

down to us, we would have

been able to guess the

calibre of the Viennese

players by the

ever-increasing difficulty

of Mozart’s orchestral

writing in his piano

concertos and operas.

These difficulties were

the object of complaint in

other parts of Europe, and

in Italy well into the

19th century his operas

were considered impossible

to perform.

Vienna did not have a

single large orchestra of

international reputation,

comparable to, for

example, the Mannheim

Orchestra, the opera

orchestras of Milan and

Turin, or the orchestra of

the Concert des amateurs

in Paris. Unlike in Paris

and London, there was no

flourishing

music-publishing industry

in Vienna. The Imperial

Court Orchestra was in a

period of severe decline.

But Vienna was the

economic, political and

cultural centre of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire,

which encompassed not just

Austria and Hungary, but

substantial portions of

present-day

Czechoslovakia, northern

Italy, Yugoslavia and

Rumania. Many wealthy

noble families from those

regions maintained homes

in Vienna. A surprising

number of them were

musically literate and

demanded a steady flow of

music of the highest

quality. It was thus no

coincidence that, along

with dozens of lesser

composers, Gluck, Haydn,

Mozart, and Beethoven -

none of whom were natives

of Vienna - preferred that

city to all others.

Mozart’s decision to stay

in Vienna in 1781 was

based not only on its

reputation but on

firsthand experience. He

had spent almost three

months in Vienna in 1762

when he was six, more than

a year there in 1767-68

when he was twelve, and

two months in 1773 when he

was seventeen. There are

no symphonies from the

first visit, for even the

precocious Wolfgang did

not write symphonies at

the age of six. By 1767,

however, he had several

symphonies to his name,

and during the 1767-68

visit to Vienna

contributed a few more to

the genre. He may have

written a symphony during

his brief stay in 1773,

but in any case he was

inspired by what he heard

to write several after his

return to Salzburg (see

the notes to volume 4 of

this series). And, of

course, it was after

settling permanently in

the Imperial capital that

he wrote

his most famous essays in

the genre: the Haffner,

the Prague, the Linz,

the Symphony in Eb, K.

543, the 'Great' G minor

Symphony, and the Jupiter.

Thus, however much the

formation of Mozart’s

symphonic style owed to

the Italian sinfonia,

to the 'English'

symphonies of J.C.

Bach and C.F. Abel, to the

brilliant orchestral

writing of the Mannheim

composers, and to local

Salzburg traditions, there

was also an early and

continuing Viennese

influence, culminating in

the final flowering of

symphonic masterpieces.

The theatre orchestras of

Vienna needed a constant

supply of symphonies to

serve as overtures to

plays, Singspiele,

and operas. High Mass in

Saint Stephen's Cathedral,

and perhaps in some of the

other large churches of

the City, was sometimes

embellished with

symphonies. During Lent,

Advent and on holy

festivals of the

liturgical calendar, stage

works were replaced by

oratorios and concerts

(called 'academies')

requiring further

symphonies. (There were no

concert halls as such; the

academies took place in

the theatres and in large

rooms found in palaces, in

taverns and in other

commercial buildings.) The

nobility and the court had

their private concerts

which, when they were

orchestral, also needed

symphonies. Finally,

another of Vienna's charms

was a surprising amount of

outdoor music-making -

events of a sort that

leave no historical traces

in the form of newspaper

announcements, posters or

programmes. A description

from the early 1790s

serves to suggest that

this too was an arena in

which Mozart’s symphonies

may have been heard:

'During the summer

months... one will meet

serenaders in the streets

almost daily and at all

hours... They do not,

however, consist as in

Italy or Spain of a vocal

part with the simple

accompaniment of a guitar

or mandolin... but of

trios, quartets (most

frequently from operas) of

several vocal parts, of

wind instruments,

frequently of an entire

orchestra; and the most

ambitious symphonies are

performed... It is just

these nocturnal musicales

which demonstrate... the universality

and the greatness of the

love of music; for no

matter how late at night

they take place... one

soon discovers people at

their open windows and

within a few minutes the

musicians are surrounded

by a crowd of listeners

who rarely depart until

the serenade has come to

an end.'

The variety of

occasions on which

symphonies were performed

goes a long way to

explaining why so many

hundreds of Viennese

symphonies survive from

the 18th century.

Having suggested the

influence of Vienna’s

orchestral traditions and

of its vigorous symphonic

school on Mozart’s

symphonies, the matter

must at once be qualified.

The Haffner

symphony was written for

Salzburg, the Linz

and Prague for the

cities whose names they

bear, and the final

trilogy possibly for an

aborted trip to England.

All were, in the event,

presumably pressed into

use for Viennese concerts;

but it seems that,

although Mozart felt the

need constantly to write

new piano concertos for

his own use, when in need

of symphonies he remained

content most of the time

to perform his own older

works, or sometimes those

by other composers. Thus,

for instance, we find him

writing to his father in January

1784, asking to be sent

four of his symphonies

from 1773-77 for his

concerts in Vienna.

As there was no single

orchestra dominating

Viennese musical life and

with which Mozart’s

symphonic activities there

can be connected, we have

for these performances

recreated a typical

Viennese ensemble,

avoiding both the

extremely small groups

that not infrequently

performed at private

concerts and the huge

groups occasionally

gathered together for

special events. In the

latter category a concert

of 1781 is usually

mentioned, at which a

symphony of Mozart’s was

performed by an orchestra

whose strings were

20-20-10-8-10, and the

wind all doubled except

for the bassoons, which

were tripled! (This

exceptionally large

orchestra was a

traditional part of the

annual Lenten benefit

concert given by the

'Society of Musicians' to

aid the widows and orphans

of musicians. It was a

feature of this special

event that every available

performer should join in

supporting the cause.)

Mozart reported to his

father that 'the symphony

went magnificently and had

every success'. A great

deal of rubbish has been

written about the possible

implications of this

event, suggesting that if

Mozart was so very

pleased, then this must

have been the sort of

orchestra he would have

preferred but usually

could not muster. However,

one must reckon with the

extreme defensiveness of

Mozart’s letters to his

father, in which he can be

observed constantly

striving to be

entertaining and to make

his affairs sound more

brilliant than they in

fact were. Then we must

remember that, even if the

symphony 'went

magnificently and had

every success', we do not

therefore have Mozart’s

opinion about what sort of

an orchestra he would have

preferred to lead on a

regular basis. He must

have been keenly aware

that in enlarging an

orchestra one traded

clarity, flexibility and

intimacy for power and

brilliance, and in the

long run he may or may not

have wanted such an

exchange. Finally, the

orchestras upon which

Mozart’s training and

taste were formed and for

which he most often

composed, in Vienna and

elsewhere, were usually of

middling size, rather than

the tiny private groups or

the occasional mammoth

extravaganzas. (The

exception was the small

but distinguished Prague

orchestra, with whom

Mozart developed a special

relationship.) He was a

practical musician who

wrote for the customary

performing conditions of

his day, and we should not

foist upon him exceptional

circumstances which can be

seen with hindsight to

prefigure later trends.

Thus, for our recordings

of the 'Viennese'

symphonies, we have

employed strings numbering

7-6-4-3-3, a pair each of

the necessary woodwind and

brass, and kettledrums.

Performance Practice

The use of

18th-century instruments

with the proper techniques

of playing them gives to

the Academy of Ancient

Music a vibrant,

articulate sound. Inner

voices are clearly audible

without obscuring the

principal melodies. Subtle

differences in

articulation are heard

more distinctly than is

usually the case with

modern instruments. The

observance of all of

Mozart’s repeats restores

many previously truncated

movements to their just

proportions, yet, perhaps

owing to the lively tempos

and luminous timbre, does

not make them seem too

long. A special instance

concerns the da capos of

the minuets, where, oral

tradition tells us, the

repeats should be omitted.

But, as we were unable to

trace that tradition as

far back as Mozart’s time,

we

experimented by observing

those repeats as well.

Missing instruments

understood in 18th-century

practice to be required

have been supplied: these

include bassoons playing

the bass line along with

the cellos and double

basses, kettledrums

whenever trumpets are

present, and the

harpischord or fortepiano

continuo. No conductor is

needed, as the direction

of the orchestra is

divided in true 18th-century

fashion between the

concertmaster and the

continuo player, who are

placed so that they can

see each other and are

visible to the rest of the

orchestra. The absence of

a conductor does not mean

that there is no

interpretation, but rather

that quite a different

type of interpretation,

arrived at by different

means, becomes possible.

As there was wide

variation in orchestral

practice

from region to region in

western Europe, no

all-purpose classical

orchestra could be

recreated; rather, we have

attempted to present the

several kinds of ensembles

for which Mozart Wrote,

and whose peculiarities he

had in mind While he

composed.

Musical Sources and

Editions

Until recently performers

of Mozart’s symphonies

have relied solely upon

editions drawn from the

old Complete Works,

published in the 19th

century by the Leipzig

firm of Breitkopf & Härtel.

During the past three

decades, however, a new

complete edition of

Mozart’s works (NMA)

has been appearing,

published by Bärenreiter

of Kassel in collaboration

with the Mozarteum of

Salzburg. The NMA

has been used for those

works for which it was

available (in this volume,

only for K. 550). For K.

425a the Diletto

musicale edition by

Charles H. Sherman was

used; for K. 45b,

Einstein's C.F. Peters

edition. For the other

symphonies, editions

have been created

especially for these

recordings.

A Note Concerning the

Numbering of Mozart's

Symphonies

The first

edition of Ludwig Ritter

von Köchel's

Chronological-Thematic

Catalogue of the

Complete Works of

Wolfgang Amaadé

Mozart was published

in 1862 (=K1).

It

listed all of the

completed works of Mozart

known to Köchel

in what he believed to be

their chronological order,

from number 1 (infant

harpsichord work) to 626

(the Requiem). The second

edition by Paul Graf von

Waldersee in 1905 involved

primarily minor

corrections and

clarifications. A

thoroughgoing revision

came first with Alfred

Einstein's third edition,

published

in 1936 (=K3).

(A reprint of this edition

with a sizeable supplement

of further corrections and

additions was published in

1946 and is sometimes

referred to as K3a.)

Einstein changed the

position of many works in

Köchel's

chronology, threw out as

spurious some works Köchel

had taken to be authentic,

and inserted as authentic

some works Köchel

believed spurious or did

not know about. He also

inserted into the

chronological scheme

incomplete works,

sketches, and works known

to have existed but now

lost. These Köchel

had

placed in an appendix (=Anhang,

abbreviated Anh.)

without chronological

order. Köchel's

original numbers could not

be changed, for they

formed the basis of

cataloguing for thousands

of publishers, libraries,

and reference works.

Therefore, the new numbers

were inserted in

chronological order

between the old ones by

adding lower-case letters.

The so-called fourth and

fifth editions were

nothing more than

unchanged reprints of the

1936 edition, without the

1946 supplement. The sixth

edition, which appeared in

1964 and was edited by

Franz Giegling, Alexander

Weinmann, and Gerd Sievers

(=K6),

continued Einstein's

innovations by adding

numbers with lower-case

letters appended, and a

few with upper-case

letters in instances in

which a work had to be

inserted into the

chronology between two of

Einstein's lowercase

insertions. (A so-called

seventh edition is an

unchanged reprint of the

sixth). Hence, many of

Mozart's works bear two K

numbers, and a few have

three.

Although it was not Köchel's

intention in devising his

catalogue, Mozart's age at

the time of composition of

a work may be calculated

with some degree of

accuracy from the K

number. (This works,

however, only for numbers

over 100). This is done by

dividing the number by 25

and adding 10. Then, if

one keeps in mind that

Mozart was born in 1756,

the year of composition is

also readily approximated.

The old Complete Works of

Mozart published 41

symphonies in 3 volumes

between 1879 and 1882,

numbered 1 to 41 according

to the chronology of K1.

Additional symphonies

appeared in supplementary

volumes and are sometimes

numbered 42 to 50,

even though they are early

works.

©

1982

Neal Zaslaw

Bibiography

- Anderson,

Emily: The Letters

of Mozart & His

Family (London,

1966)

- Burney,

Charles: The

Present State of

Music in Germany,

The Netherlands, and

United Provinces

(London, 1773)

- Della

Croce, Luigi: Le

75 sinfonie de

Mozart (Turin,

1977)

- Eibl,

Joseph Heinze, et al.:

Mozart: Briefe und

Aufzeichnungen

(Kassel, 1962-75)

- Koch,

Heinrich: Musilcalisches

Lexikon

(Frankfort, 1802)

- Landon,

H. C. Robbins: 'La

crise romantique dans

la musique

autrichienne vers

1770: quelques

précurseurs inconnus

de la Symphonie en sol

mineur (KV 183) de

Mozart', Les

influences étrangères

dans l'oeuvre de W.

A. Mozart

(Paris, 1958)

- Larsen,

Jens

Peter: 'A Challenge to

Musicology: the

Viennese Classical

School', Current

Musicology

(1969), ix

- Mahling,

Christoph-Hellmut:

'Mozart und die

Orchesterpraxis seiner

Zeit', Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1967)

- Mila,

Massimo: Le

Sinfonie de Mozart

(Turin, 1967)

- Saint-Foix,

Georges de: Les

Symphonies de Mozart

(Paris, 1932)

- Schneider,

Otto, and Anton

Algatzy: Mozart-Handbuch

(Vienna, 1962)

- Schubart,

Ludwig: Christ, Fried.

Dan. Schubart's

Ideen zu einer

Asthetik der

Tonkunst

(Vienna, 1806)

- Schultz,

Detlef: Mozarts Jugendsinfonien

(Leipzig, 1900)

- Sulzer,

Johann

Georg: Allgemeine

Theorie der schönen

Künste

(Berlin, 1771-74)

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'The Compleat

Orchestral Musician',

Early Music

(1979), vii/1

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'Toward the

Revival of the

Classical Orchestra',

Proceedings of the

Royal Musical

Association

(1976-77), ciii

|

|

Symphony in

F

major, K.42a

(76)

Although the attribution

of this attractive

symphony to Mozart is

fraught with problems,

the work's authenticity

has apparently never

previously been

seriously challenged.

There is no autograph

manuscript or other

reliable source stemming

from Mozart or his

circle. The symphony’s

sole source was a set of

18th-century manuscript

parts found in the

archives of the Leipzig

music publishers,

Breitkopf & Härtel.

In

accepting this work, Köchel

followed his friend Otto

Jahn,

who in his great Mozart

biography reported that

in the Breitkopf

archives he had found a

collection of twenty

symphonies attributed to

Mozart. Ten of these

were also listed in Johann

André's collection of

Mozartiana, which, as it

had been received

directly from Mozart’s

widow, was not to be

questioned. (The

assumption of the total

reliability of the André

holdings has

subsequently proved to

be not entirely

correct.) A further two

of the twenty were

symphony versions of the

overtures to Lucio

Silla and II

sogno di Scipione.

The remaining eight,

owing to the company in

which they were fund,

could therefore be

adjudged genuine. Jahn

dated the sympony ’177?’

while Köchel

ventured 'perhaps 1769'

- both presumably

on stylistic grounds. On

the weighty authority of

Jahn

and Köchel,

the symphony was

published in a

supplementary fascicle

of the Old Complete

Works in 1881, the only

edition the work has

ever had.

In their detailed survey

of Mozart’s output,

Wyzewa and Saint-Foix

placed K.42a in Salzburg

between 1 December 1766

and 1 March 1767. They

suggested - on the basis

of perceived

similarities between the

first movement of this

work and the overture to

Die Schuldigkeit des

ersten Gebots,

K.35, and on the basis

of comparisons with

Mozart’s earliest

symphonies - that K.42a,

’...was composed before

the overture, perhaps

around the month of

December 1766. It

is the great piece that

the child wrote, with

extreme effort and care,

when, returning to

Salzburg [from his grand

tour to Paris, London

and Holland], he wished

to show his master and

his compatriots

everything he had

learned during his

travels.'

To call this

'speculation' is perhaps

too generous; it is

sheer fantasy.

The great Mozart

biographer Hermann Abert

examined the arguments

of Wyzewa and Saint-Foix

and, while questioning

the similarities they

had proposed between K.42a

and the overture to

K.35, agreed with them

that the work must be

earlier than Köchel

had thought. Finally, in

the third edition of the

Kochel Catalogue (K3),

Einstein gave as the

supposed date of this

orphaned work, 'autumn

1767 in Vienna'. The

basis for this judgment

was not explained, but a

seemingly unrelated

remark may reveal his

line of reasoning. The

minuet of this symphony,

Einstein wrote, 'is of a

relatively so much

greater maturity than

the other three,

primitive movements,

that we may accept that

it was composed later.

As Einstein claimed that

Viennese symphonies were

nearly always in four

movements (which is not

nearly as firm a

principle as he would

have us believe) and

that Mozart was in the

habit of adding minuets

and trios to

three-movement

symphonies written for

other places to tailor

them for Vienna, he must

have thought that the

(hypothetical) addition

of a minuet and trio to

K.42a associated it with

one of Mozart’s visits

to the Imperial capital.

In any case, this

rootless symphony has

retained the assignment

'allegedly in autumn

1767 in Vienna' in K6

(the sixth edition of Köchel's

Catalogue), and we have

kept it there for lack

of better information.

At present, further

documentary study of

K.42a is impossible, for

there are no known

primary sources of the

work, and the sole

secondary source (the

parts in the Breitkopf

archives) was lost or

destroyed during World

War II.

Unlike some other

symphonies uncertainly

attributed to Mozart,

this one at least does

not have a conflicting

attribution to another

composer. If,

however, we are indeed

to judge it by the

company it kept in the

Breitkopf archives, then

we must report that

seven of the twenty

symphonies mentioned by

Jahn

remain to this day

without autographs or

other reliable sources.

A striking feature of

the first movement is

the prominence of the

wind, which, in addition

to the usual pairs of

oboes and horns,

include a pair of

obbligato bassoons.

Wyzewa and Saint-Foix

singled out for mention

'the oboe and bassoon

solos, the constant

exchanges of melodic

ideas between the wind

and strings. In

regarding this as a

progressive trait, they

must have had in mind

the brilliant and

innovative concertante

wind writing in Mozart's

late operas, symphonies

and piano concertos.

Perhaps they considered

K.42a a step in that

direction. But they

failed to notice how

very uncharacteristic

this wind writing was

for Mozart, for this or

any other time. In

his early symphonies,

the expositions of the

first movements

typically begin and end

tutti, forte,

often with semiquaver

tremolos in the strings

adding to the bustle. In

the middle of the

exposition, however,

quieter, lyrical

sections usually appear,

corresponding with the

arrival of the dominant,

at which some or all of

the wind fall silent.

This use of

orchestration serves

several important

functions: it highlights

the movements' dynamics

by the wind

reinforcement of the tuttis,

it underlines the

contrast of character

that is a hallmark of

the galant style, it

clearly signals to the

ear the movement’s

structure, and it gives

the wind players a

breathing space. This

arrangement was an

absolutely standard part

of Mozart’s style of

that period. In the

first movement K.42a,

however, the wind never

stop blowing, thereby

giving the movement an

uncharacteristically

uniform timbre

throughout. Have we the

right to deny Mozart an

experiment? Of course

not. We revel in his

experiments. But was

this one of them?

The alluring andante,

with its sustained

bassoons and

mandoline-like pizzicato

passages, would have

been very much at home

as a serenade in a

sentimental opéra

comique of the

period, as Della Croce

suggests. The particular

excellence of the minuet

has already been

mentioned. The trio,

rather unusually, is

based on an idea drawn

from the minuet - an

idea with a slightly

exotic contour. The

opening idea of the

finale bears a striking

resemblance to a popular

gavotte from Rameau's Temple

de la gloire (Act

III, scene iii), as

Wyzewa and Saint-Foix

were the first to point

out; but for the rest

the two movements are

entirely dissimilar.

Symphony in F major,

K.43

With this work we escape

from the bibliographical

swamps of the previous

symphony and find

ourselves again on terra

firma. The

autograph

manuscript-abeautifully-written

fair-copy found among

the manuscripts formerly

in Berlin but now in

Kraków -

bears the heading Sinfonia

di Wolfgango Mozart à

Vienne 1767. Above

'1767' was written

(apparently in Leopold

Mozart’s hand) 'à

olmutz 1767,'

but this was

subsequently crossed

out. The Mozarts visited

the North Moravian town

of Olmutz, or Olomouc,

on only one, unhappy

occasion, between

approximately 26 October

and 23 December 1767.

They had fled there from

Vienna in the vain hope

of avoiding an outbreak

of smallpox, to which

however both Wolfgang

and Narmerl eventually

succumbed, and from

which both recovered.

From the inscriptions on

the autograph, Einstein

in K3 concluded that

K.43 must have been

begun either in Vienna

in the autumn and

completed in Olomouc, or

begun in Olomouc and

completed in Vienna at

the end of December, and

the editors of K6

concur. But K.43 cannot

have been completed in

Vienna at the end of

December 1767 for,

although the Mozarts did

indeed leave Olomouc

around 23 December, they

reached Vienna only on

10 January

of the new year. The

reason for the slowness

of their journey was

this: in the course of

their flight from Vienna

they had stopped at Bmo

(Brünn),

where the Count von

Schrattenbach (the

Archbishop of Salzburg’s

brother) had arranged

that they give a

concert. Leopold wanted

his children even

further from Vienna’s

smallpox epidemic,

however, so he postponed

the concert until their

return trip. Hence the

Mozarts returned to Brno

on Christmas Eve, and on

30 December they gave

their concert, which was

duly noted in the diary

of a local clergyman:

'In the evening... I

attended a musical

concert in a house in the

city known as the 'Taverna',

at which a Salzburg boy

of eleven years and his

sister of fifteen years,

accompanied on various

instruments by

inhabitants of Brünn,

excited everyone’s

admiration; but he could

not endure the trumpets,

because they were

incapable of playing

completely in time with

one another.'

The report of

Wolfgang's reaction has

the ring of truth to it,

for his extreme

sensitivity to trumpets

in his childhood is

documented elsewhere.

Trumpets aside, however,

if Leopold Mozart was

anything other than

pleased with the local

orchestra, he was polite

enough to hide the fact,

for the leader of the

Brno waits reported

that:

'Mr Mozart, Kapellmeister

of Salzburg, was

completely satisfied

with the orchestra here

and would not have

believed that my

colleagues could

accompany so well at the

first rehearsal.'

We propose the following

hypothetical scenario

for K.43: it was

composed in Vienna

between 15 September and

23 October 1767, copied

over in Olomouc after

Wolfgang's recovery from

smallpox, and may have

received its première

on 30 December in Brno.

But what could the

trumpets have been

playing? As they come

down to us, none of the

symphonies composed by

Wolfgang prior to the

end of 1767 calls for

trumpets. Among his

other orchestral works,

only a pastiche keyboard

concerto, K.40, an

offertory, K.34, and a

recitative and aria,

K.33i (36), call for

trumpets. An offertory

would not have been

perfonned at a concert

in a tavern, and in any

case there is indirect

evidence suggesting that

the Mozarts had brought

none of these three

works with them on tour.

The most likely

explanation, therefore,

is that at least one of

Mozart’s earliest

symphonies did once have

trumpet parts, which, as

was sometimes the case

with Mozart and his

contemporaries, were

optional and notated

separately from the

score. This suggestion

is made the more

plausible by a document

written by Nannerl (and

reproduced in the

introduction to K.16 in

volume l of this series)

in which she recalled

that Wolfgang's 'first'

symphony employed

trumpets. K.43 would not

have been one of the

symphonies with optional

trumpets, however, for

Mozart’s usual trumpet

keys were C, D, and Eb

major.

As the provenance of the

previous work is so

uncertain, we may

provisionally regard

K.43 as Mozart’s first

four-movement symphony,

all of the earlier ones

having been in three

movements.

The first movement opens

with a fanfare identical

to that used by J.C.

Bach, Johann

Stamitz, and Dittersdorf

to launch symphony

movements. Then follows

a so-called Mannheim

crescendo, the turn to

the dominant, the

opening fanfare in the

bass with tremolo above,

a lilting theme (strings

alone, piano)

and the energetic

closing section of the

exposition. A concise

development section,

based on the fanfare in

the bass and some new

material, leads to the

lilting theme, now in

the tonic, and the

recapitulation of the

rest of the exposition.

The andante presents a

strikin change of

orchestra colour,

created by a new key

(C major), flutes

replacing oboes, first

violins muted, second

violins and bass

instruments pizzicato,

and violas, divisi,

murmuring in

semiquavers. The

movement is an

arrangement of the

eighth number of

Mozart’s Latin comedy Apollo

et Hyacinthus

(concerning which see

the discussion of K.38

in volume 2 of this

series). The Greek

legend of Apollo and

Hyacinth relates that

both Zephyr andp Apollo

loved a youth, Hyacinth,

who, however, cared only

for Apollo. When out of

jealousy Zephyr killed

Hyacinth, Apollo turned

his blood into the

flower that to this day

bears his name. The

duet, which serves as

the second movement of

the present symphony,

occurs near the end of

the opera after the

story’s action is

finished. Two subsidiary

characters muse in a

rather abstract,

allegorical vein about

divine anger and loss of

grace. The

eleven-year-old prodigy,

perhaps finding little

specific in the words to

inspire him, seems to

have set the situation

rather than the text,

composing a movement of

almost

sublime serenity.

A particularly luminous

minuet and quirky trio

prepare us for the

energetic 6/8 finale.

The symphony appears to

have been written con

amore

throughout, and is one

of the best works

produced by the

eleven-year-old

Wolfgang.

Symphonies in D

major, K.45 and K.46a

(51)

The existence of two

versions of the same

symphony offers us a

precious opportunity to

learn something further

about the conditions

under which the youthful

composer worked. The

autograph of K.45, now

in West Berlin, bears

the inscription Sinfonia

di Sig[no]re Wolfgang

Mozart/1768, 16 Jener

- thus it was completed

just a few days after

the return to Vienna

from the journey to

Olomouc and Brno

chronicled in the notes

to the previous work.

There is no record of

the Mozarts giving a

public concert at this

time, so we must assume

that this symphony was

written for one of

Vienna's many private

concerts. The Mozarts

had a

two-and-a-half-hour-long

audience with Maria

Theresa and her son, the

recently crowned Emperor

Joseph

II,

only three days after

the completion of K.45.

Music was discussed

during the audience and

Wolfgang and Nannerl

performed, but as none

of the court musicians

were present no

orchestral music can

have been played. It was

apparently on this

occasion that Joseph

suggested that Wolfgang

write an opera for

Vienna - an opera that

will feature in this

tale of two symphonies.

The earliest occasion on

which, as far as we

know, K.45 could have

been heard was near the

end of March at a grand

Lenten concert which,

Leopold reported to his

friends in Salzburg,

'was given for us at the

house of His Highness

Prince von Galitzin, the

Russian Ambassador’ .

The precise date and

contents of this

programme are not known,

but the Mozarts’ usual

custom was to begin and

end with symphonies,

filling the middle of

the event with arias,

concertos, chamber

music, two- and

four-hand keyboard music

played by Wolfgang and

Nannerl, and keyboard

irnprovisations by

Wolfgang. K.45 is, like

K.43, in the

four-movement format

favoured in Vienna for

concert purposes.

By the time of the

Russian ambassador's

concert, Leopold Mozart

had already overstayed

the leave of absence

granted him from his

duties at the Salzburg

Court, and the

Archbishop had issued an

order stopping his pay

until he returned. The

reason that he had not

returned to Salzburg was

that - following the

Emperor's suggestion -

Wolfgang had indeed

composed a comic opera,

La finta semplice,

K.46a (51), but its

production was

repeatedly delayed as a

result of jealous

intrigues on the part of

several Viennese

musicians. Rumours were

being circulated that

Wolfgang was a fraud,

and that his father did

his composing for him.

Leopold, a man with an

acute sense of honour,

felt that he could not

leave Vienna before he

and his son were

vindicated. Yet although

he battled valiantly

against his opponents,

even to the point of

appealing directly to

the Emperor, the opera

remained unperformed in

Vienna. (The Mozarts

were able to retreat

with their honour intact

only because Wolfgang

was permitted to

compose, and direct the

performance of, the

music for the

consecration of a new

church, a gala occasion

at which the entire

court was present.) The

overture for the

illfated la finta semplice

was a re-working of

Wolfgang’s last

symphony, K.45.

The changes he wrought

in turning a concertor

chamber-symphony into an

overture-symphony are

revealing. He omitted

the minuet and trio. He

altered the

orchestration, adding

pairs of flutes and

obbligato bassoons to

the original pairs of

oboes and horns, while

dropping the trumpets

and kettledrums.

The additions were

perhaps to be expected,

for, as we can easily

imagine, the opera house

in Vienna had at its

disposal larger

orchestral resources

than had most private

concerts; but the

dropping of the trumpets

is surprising, since

operas of the period so

often call for them to

lend verisimilitude to

ceremonial and military

scenes. Perhaps a comic

opera could dispense

with these accoutrements

of the nobility.

Wolfgang also added a

considerable number of

phrasing and dynamic

indications to the

re-worked symphony.

Whether these represent

a spelling-out of ideas

implicit in K.45 (and

conveyed in rehearsal to

the orchestra by

Wolfgang leading from

the harpsichord) or

whether they represent a

re-thinking of the

piece, cannot be

ascertained. But in the

preparation of the

versions recorded here,

care was taken that the

members of the Academy

of Ancient Music

rehearsed and recorded

K.45 before looking at

K.46a, so that ideas

that Wolfgang may not

yet have thought of at

the time he conceived

the former could not be

added to the latter

through unhistorical

hindsight. He also

altered the metre of the

andante from C to CI,

and the melody’ s

quavers to dotted

quavers and semiquavers.

Finally, Wolfgang added

two additional bars of

music to the first

movement and four to the

finale. It would be nice

to think that in the

addition of these bars

we catch a glimpse of

him refining the

symphony' s proportions,

but the truth may be

something more mundane.

In the case of the first

movement, a bar that was

present in the

exposition had been

lacking in the

recapitulation while an

entirely different bar

that was present in the

recapitulation had been

lacking in the

exposition. Wolfgang

merely brought the

exposition and

recapitulation into

conformity and the

differences between them

may simply have been the

results of a lapse of

memory, rather than a

new artistic discovery.

In the finale, the

changes were to the

ending. The last two

bars of K.45

were replaced first with

two bars that led

directly into the

opera’s opening chorus

and then, when Wolfgang

wanted to use the

overture of K.46a as an

autonomous work, with a

concert ending that

incorporated the two

original bars, the two

new bars, and two

additional ones.

The finale is based on a

time that was to enjoy

considerable popularity

in London around 1800

under the name 'Del

Caro’s Hornpipe’. A

similar time also

appears in the Intrada

of Leopold Mozart’s Musical

Sleigh-ride. The

origins of this

tune-type are

undoubtedly lost in the

mists of oral tradition.

Symphony in G major,

K.deest

The Benedictine

monastery at Lambach,

near Wels in Upper

Austria, was a

convenient resting place

for the Mozart family on

their journeys between

Salzburg and Vienna.

Like many other Bavarian

and Austrian monasteries

of the time, Lambach

provided rooms and meals

for travellers, and

maintained an orchestra

to ornament

its liturgy and

to provide

entertainment. Amand

Schickmayr, a friend of

Leopold Mozart from the

days when both men were

students at Salzburg

University, had been at

Lambach since 1738 and

had become abbot of the

monastery in 1746. At

the beginning of January

1769 the Mozart family,

returning to Salzburg

from their second trip

to Vienna, stopped at

Lambach. We do not know

how long they remained

there on this occasion,

as the visit is not

mentioned in the

family’s letters or

diaries, and in fact is

known to us solely from

inscriptions on two

musical manuscripts.

The manuscripts in

question are sets of

parts for two symphonies

in G major, one

inscribed Sinfonia/a

2 Violini/2 Oboe/2

Corni/Viola/e/Basso./

Del Sig[no]re

Wolfgango/Mozart./Dona

Authoris/4ta Jan.

769, and the other

bearing an identical

inscription except that

in place of 'Wolfgango'

there appears

'Leopoldo'. For

convenience of

reference, the symphony

ascribed to Wolfgang at

Lambach

will be referred to here

as 'K.45a',

and that ascribed to

Leopold as 'G16'.

Until 1982 the two

symphonies were thought

to survive only in the

Lambach manuscripts,

neither of which is an

autograph. Both were

reserved in the

monastery's archives

where they

were discovered by

Wilhelm Fischer, who, in

1923, published K.45a.

Prior to that, however,

K.45a had appeared in K1

and K2 as A221, one of

ten symphonies known to

Köchel

solely by the incipits

of their first

movements, found in a

Breitkopf & Härtel

Manuscript Catalogue.

In K3 Einstein placed

the rediscovered

Symphony in G major,

A221, in the chronology

of authentic works

according to the date on

the Lambach

manuscript. Speculating

that the symphony had

been written during the

1767-8 sojourn in

Vienna, he assigned it

the number 45a,

representing the

beginning of 1768. The

editors of K6 accepted

Einstein's

and Fischer's

opinion of the

authenticity of

K.45a/A221, as did

Georges de Saint-Foix

and many others who

wrote about Wolfgang's

early symphonies, and

Einstein's dating of the

work to early 1768 was

generally accepted too.

In

1964, however, Anna

Amalie Abert published a

startling new hypothesis

about the two G-major

symphonies. She had come

to believe that - like

the accidental

interchange of infants

that underlines the

plots of a number of

plays and operas and is

given such a delightful

sendup in O’Keefe's

comedy Wild Oats

- the two works had been

mixed up, perhaps by a

monkish librarian at

Lambach. Abert based her

opinion on a close

examination of the two

symphonies,

and on comparisons

between them and other

symphonies thought to

have been written by

Leopold and Wolfgang at

about the same time.

Abert's stylistic

analysis suggested that

K.45a was written in a

more archaic style than

G16, and her aesthetic

evaluations suggested

that the former was less

well written than the

latter. She then

reasoned that, as

Leopold was the older,

the more conservative,

and the less talented of

the two composers, he

must have been the

author of K.45a and

Wolfgang of G16.

Comparing formal and

stylistic

characteristics of the

first movements of the

two symphonies with

those of the first

movements of other

symphonies of that

period by Leopold and

Wolfgang, Abert found

that the first movement

of K.45a seemed to

resemble Leopold's first

movements while the

first movement of G16

seemed to resemble

Wolfgang's. She also

pointed out the

(relative)

monothematicism of the

first movement of K.45a,

which is considered an

archaic trait, and

therefore likely to have

come from the older

composer. Certain

aspects of K.45a's

construction - the

adding together of many

two-bar phrases and

the over-use of

sequences - Abert

considered to be

characteristic of

Leopold's works; while

the more spun-forth and

varied melodic ideas of

G16 struck her as akin

to Wolfgang’s technique.

Her doubts about K.45a

had to do, 'above all

with the remarkable

plainness and monotony

of the second and third

movements, which

immediately catch the

eye of the close

observer of the

symphonies K.16 to 48'.

Accordingly, she edited

the previously

unpublished G16 as a

work of Wolfgang’s, and

it has since been

frequently performed,

recorded and discussed

as such.

Abert’s hypothesis is

not quite as highhanded

as it might at first

appear to anyone unaware

that a large number of

18th-century symphonies

survive with incorrect

attributions. For

example, leaving aside

the Lambach symphonies,

some seven symphonies

exist with attributions

to both Wolfgang and

Leopold.

In

1977-8, when this series

of recordings was being

planned, I studied

Abert’s arguments, found

them convincing, and

decided that we should

record G16 rather than

K.45a. However, in the

autumn of 1981, in the

course of research for

these notes and for a

book-in-progress about

Mozart’ s symphonies, I

re-examined Abert’s

evidence as well as some

evidence overlooked by

her, and was forced to

conclude that the

original attributions

were correct. A brief

summary of the evidence

follows.

(1) Abert found

that the stringing of

two-bar phrases in K.45a

was atypical of

Wolfgang, yet according

to Ludwig Finscher, '

...the technique of many

minor composers of the

1760s and 1770s -

including Mozart - was

to place two-bar,

fourbar, and eight-bar

sections in a row,

sometimes adding a bar,

or changing the order of

sections'. Besides, as

the more spun-forth

style (Fortspinnungstypus)

of G16 was a

late-Baroque trait and

the more segmented style

(Liedtypus) of

K.45a a galant trait,

this distinction, far

from supporting Abert’s

new attributions,

contradicts them.

(2) The manuscripts of

both Lambach symphonies

prove to be in the hand

of the Salzburg copyist

and friend of the

Mozarts', Joseph

Richard Estlinger. (This

fact was known to Abert,

but not to Einstein.)

This means that the

symphonies must have

been copied in Salzburg

before the Mozarts'

departure for Vienna in

September 1767. The

earlier that we think

K.45a was composed, the

less surprise we should

experience at finding

the apprentice-composer

writing in an 'archaic'

style. In particular,

Abert’ s comparisons of

K.45a and G16 with K.43

and 48 are much weakened

by an earlier dating of

K.45a, for if the latter

was composed in 1766 or

the first part of 1767,

then its 'immaturity’ of

style in comparison with

works from the end of

1767 and the end of 1768

is not surprising. This

was after all a period

during which Wolfgang's

musical knowledge and

craft were growing by

leaps and bounds.

(3) Mozart himself immodestly

claimed to be able to

write in any style, and

his boast is in some

measure borne out by the

manner in which he

assimilated musical

styles and ideas during

his tours.

(4) Although Leopold was

a generation older than

his son and may not have

had his son's

originality, he was

nonetheless an able,

well-informed musician.

Let us not forget that

he too made the tours

and heard the latest

musical styles of

western Europe. In

the 1760s, he was a

thoroughly up-to-date

composer, while Wolfgang

had yet to find

his distinctive 'voice'.

It is thus not difficult

to believe that during

that period father and

son may have written

symphonies in which the

fathers style was in

some aspects more modern

than the son's. And is

it not reasonable to

suspect that some of

Leopold's mature works

may have been better

constructed than some of

his son's childhood

works, in the genesis of

which he so often took

part as teacher,

advisor, editor, and

copyist?

(5) In accepting Vienna

as the place of K.45a's

creation, commentators

were made uncomfortable

by the fact that it was

in the three-movement

format of the earliest

symphonies written in

London and Holland

rather than the

four-movement format

which, as we have seen,

was favoured in Vienna

and used by Wolfgang in

the symphonies (K.43, 45

and 48) that can

confidently be assigned

to the 1767-68 sojourn

there.

(6) Then we must ask

ourselves, how plausible

is it that the

manuscripts of the two

symphonies were

interchanged? After all,

the titles and the

inscriptions 'Del

Sig[no]re Wolfgango [or

'Leopoldo'] Mozart'

on the manuscripts of

K.45a and G16

respectively were

written by the

Salzburg scribe.

Only the final words on

each manuscript, 'Dono

Authoris 4ta Jan. 769'

are in a different hand,

undoubtedly that of one

of the Lambach monks.

Are we to believe that

these two manuscripts

were accepted from a

copyist well known to

the Mozarts, carried

around by them for more

than a year, used for

performances, and

presented to the Lambach

monastery, without the

usually punctilious

Leopold having corrected

these supposedly

incorrect attributions?

(7) Finally, in 1767

Leopold Mozart assembled

six of Wolfgang’s early

symphonies to have

copied and sent to the

Prince of

Donaueschingen. New

evidence now suggests

that these six were

probably K. 16, 19, 19a,

19b, 38 and 45a. If so,

then K.45a is certainly

by Wolfgang and must

have been completed

prior to the Mozarts'

departure for Vienna on

11 September 1767.

Having reached these

conclusions in the

autumn of 1981, I worked

out my arguments in an

article for a voltune

honouring my former

professor, Paul Henry

Lang (see bibliography).

Then in April 1982 the

February issue of the Mitteilungen

der Internationalen

Stiftung Mozarteum

came into my

hands, and in it was an

article by Robert Münster,

head of the Music

Division of the Munich

Staatsbibliothek,

containing new evidence

confirming the

correctness of my

arguments in favour of

Wolfgang’s authorship

of, and an earlier date

for, K.45a. The Munich

library recently

acquired the previously

unknown, original set of

parts for K.45a. They

comprise first and

second violin parts in

an unknown hand, a basso

part in Nannerl's hand,

and the rest of the

parts in Leopold's hand.

The title page, also in

Leopold's hand, reads Sinfonia/à

2 Violini/2 Hautbois/2

Corni/Viola/e/Basso/di

Wolfgango/Mozart di

Salisburgo/à la Haye

1766. K.45a

therefore forms a

pendant to the Symphony

in Bb major, K.22, also

composed in the Hague,

and to be heard in

volume 1 of this series.

The Symphony in G major,

G16, is presented here,

according to our

original plan. It is

hoped that the other

Lambach symphony, K.45a,

will be issued on a

single record at some

future date.

Symphony in Bb major,

K.45b (A214)

This is another of the

ten symphonies known to

Köchel

solely by a

first-movement incipit,

taken from the Breitkopf

& Härtel

Manuscript Catalogue.

Prior to the publication

of K3 Einstein had

located a set of 18th-century

parts for this work in

the Berlin library

bearing the title Synfonie

Ex Bb,

a 2 Violini, 2 Oboe, 2

Corni, Viola è

Basso/Del

Sig. Cavaliere Amadeo

Wolfgango Mozart

Maestro di concerto di

S.A. à

Salisburgo.

Wolfgang received the

unpaid post of 'maestro

di concerto'

to the Salzburg Court on

14 November 1769, and

earned the right to call

himself 'Cavaliere' on 5

July

1770, when he was

decorated in Rome with

the Order of the Golden

Spur. But Einstein felt

(presumably on stylistic

grounds) that this

symphony could not have

been written later than

the beginning of 1768,

and thus he arrived at

the Köchel

number 45b. In

Einstein’s opinion,

therefore, the Berlin

manuscript constituted a

later copy of an earlier

work, and this may

indeed be correct. As an

indirect consequence of

World War II,

K.45b was published

twice, once in Leipzig,

edited by Müller

von Asow, and once in

New York, edited by

Einstein.

The discussion of the

previous symphony having

clearly revealed the

pitfalls of dating and

attribution on stylistic

grounds, perhaps nothing

further need be said on

that point other than

that the time and place

of creation of K.45b,

and perhaps even its

author, remain in

question.

The first movement is

written in a type of

sonata form in which the

ideas presented in the

exposition recur in

reverse order in the

second part, a

mirror-image technique

of which Mozart was

later to make brilliant

use (for example, K.133,

first movement). Much

has been made of the

presence in the bass

line of K.45b of the

famous motive do-re-fa-mi

of the Jupiter

symphony’s finale, but

little has been said of

the fact that it appears

too often, sometimes

awkwardly transposed to

different scale degrees.

In the andante, another

sonata-form movement but

in Eb major, the horns

are silent; the violins,

occasionally joined by

the oboes, play their

duets far above the bass

line. An eminently

danceable minuet is

contrasted by a trio in

F major for strings

only. The final allegro

in 2/4 is also in sonata

form; it brings the

symphony to a cheerful

if conventional

conclusion.

Symphony in D major,

K.48

Why, virtually on the

eve of his departure

from Vienna after a stay

of more than a year, did

Wolfgang write another

symphony? Was there a

farewell concert or a

private commission? (We

know of none.) Was

something needed

immediately upon the

retum to Salzburg? (But

surely the other

symphonies written in

Vienna could have

served?) The autograph

manuscript of this work,

now found in

West Berlin, is

inscribed Sinfonia/di

W: Mozart/1768/à

Vienna/den 13ten dec:.

On the very next day

Leopold Mozart wrote to

a friend in Salzburg his

final letter from

Vienna, but no

forthcoming event that

might explain the need

for a new symphony is

mentioned. In that

letter Leopold remarked:

'As very much as I

wished and hoped to be

in Salzburg on His

Highness the

Archbishop's

consecration day [21

December], nonetheless

it was impossible, for

we could not bring our

affairs to a conclusion

earlier even though I

endeavoured strenuously

to do so. However, we

will still set out from

here before the

Christmas holiday...'

As we have seen, the

Mozarts were long

overdue at Salzburg, and

Leopold's pay was being

withheld. We might

expect, under these

circumstances, that they

would have left Vienna

almost immediately after

Wolfgang' s triumph on 7

December, when he led

his own mass

(K.47a/139), offertory

(K.47b) and trumpet

concerto (K.47c) in the

presence of the Imperial

Court and a large crowd

of onlookers. Yet

something held the

Mozarts in Vienna for

more than a fortnight

after that. That

'something' may have

been the unknown

occasion for which K.48

was written, perhaps a

farewell concert in the

palace of one of the

nobility.

Like K.45, K.48 is in

the festive key of D

major and calls for trumpets

and kettledrums in

addition to the usual

strings and pairs of

oboes and horns.

Like both K.43 and 45,

K.48 is in four

movements. Its opening

allegro, in 3/4 rather

than the more customary

common time, begins with

a striking idea

featruing dotted minims,

alternately forte

and piano. In

the space of a mere six

bars this melody covers

a range of

two-and-a-half octaves.

It is soon followed by

nervous quavers in the

bass line and running

semiquavers in the

violins, which, with an

occasional comment from

the oboes and one

dramatic silence, lead

the energetic exposition

to its conclusion. The

movement, like all four

in this symphony, has

both halves repeated.

The development section,

exceptionally for this

period in Mozart's life,

is nearly as long as the

exposition; in the

course of its

modulations it reviews

the ideas already heard.

The recapitulation gives

them again in full, and

the movement thus

provides a lucid

demonstration of James

Webster’s seemingly

paradoxical description

of sonata form as "a

twopart tonal structure,

articulated in three

main sections" (The

New Grove).

The andante, in G major

2/4 for strings alone,

is a charming little

song in binary form. The

peculiar character of

the opening idea is

owing to its

harmonization in

parallel 6-3 chords and

the rather sing-song

quality of its melody,

which almost reminds one

of the tune to a nursery

rhyme. This leads,

however, to a second,

more Italianate, idea,

which, with its larger

range and insistent

appogiaturas, conveys a

much more operatic

impression.

The minuet reinstates

the wind, although the

trumpets and drums drop

out for the contrasting

G-major trio. Here

Mozart perfectly

captured the stately

pomp that Viennese

symphonic minuets

of the time provided as

a kind of aesthetic

stepping-stone between

the Apollonian slow

movement and the

Dionysiac finale, which

in this case is a 12/8

jig in a large, binary

design.

Symphony in Bb major,

K.AC11.03 (74g, A216)

The story behind this

symphony is just as

peculiar as that of the

Lambach symphonies. Like

K.45a and 45b, this work

was known to Köchel

only by its incipit in

the Breitkopf Manuscript

Catalogue. Sometime

shortly after the turn

of the 20th century,

however, a set of parts

was discovered in the

Berlin library, and the

work was published by

Breitkopf & Härtel

in 1910. According to a

detailed list in K6

showing the contents of

the Old Complete Works,

this edition formed the

final fascicle of the

supplementary voltunes,

as 'Serie 24, No. 63'.

And indeed, like other

Mozart scores published

by Breitkopf as

offprints from the

Complete Works, the copy

of K.74g available to me

has at the top of the