|

|

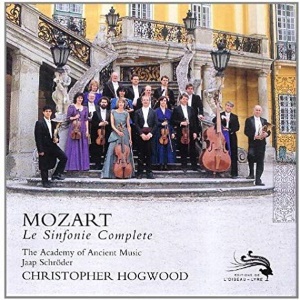

4 LP's

- D172D4 - (p) 1983

|

|

| 3 CD's -

421 085-2 - (c) 1988 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| The Symphonies

- Vol. 6 - Nos. 31, 35, 38, 39, 40 &

41 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

38' 29" |

|

Symphony No. 31

"Paris" (1st version) in D Major,

K. 297 / K. 300a

|

16' 50" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro assai · Andante · Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 35 "Haffner" ( 2nd version) in

D Major, K. 385 |

21' 39" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro con spirito · Andante ·

Menuetto & Trio · Finale

(Presto)] |

|

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

62' 15" |

|

| Symphony

No. 39 in E flat Major, K. 543 |

30' 40" |

|

|

| - [Adagio-Allegro

· Andante con moto · Menuetto

& Trio (Allegretto) · Finale

(Allegro)] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 38 "Prague" in D Major, K. 504 |

31' 35" |

|

|

| - [Adagio-Allegro

· Andante · Presto] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

58' 12" |

|

| Symphony

No. 31 "Paris" (2nd version) in D

Major, K. 297 / K. 300a |

22' 39" |

|

|

| - [Allegro vivace

· Andante · Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 40 (1st version) in G Minor,

K. 550 |

|

|

|

| - [Molto allegro] |

6' 59" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - [Andante ·

Menuetto & Trio (Allegretto) ·

allegro assai] |

28' 34" |

|

|

| Long Playing

4 |

|

37' 54" |

|

| Symphony

No. 41 "Jupiter" in C Major, K.

551 |

|

|

|

| - [Allegro vivace

· Andante cantabile] |

20' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - [Menuetto &

Trio (Allegretto) · Molto allegro] |

17' 40" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap Schröder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

|

|

| Violins |

Jaap

Schröder (Jakob Stainer 1665 )

- Catherine Mackintosh

(Rowland Ross 1978, Amati) - John

Holloway (Mariani 1650) - Monica

Huggett (Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Simon Standage

(Rogeri, Brescia 1699) - Alison

Bury (Rowland Ross 1979

[Stradivarius 1688]) - Micaela

Comberti (Anon.,

England, circa 1740) - Roy

Goodman

(Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Miles Golding (Anon.,

Austria, circa

1780) - David Woodcock (Anon.,

circa 1775) -

Julie Miller (Rowland Ross

1979 [Amati])

- Roderick

Skeaping

(Charles and

Samuel

Thompson c.

1780) - Elizabeth Wilcock

(Grancino, Cremona 1652) - Christopher

Hirons (Duke, circa

1775) - Graham Cracknell

(Richard Duke 1787) - Roy

Mowatt (Rowland Ross

1979 [Stradivarius 1715]) -

Susan

Carpenter-Jacobs

(Rowland Ross 1979

[amati 1649]) - Kay Usher (Henry Jay 1770

London) - Joan Brickley (Metzel,

Nürnberg 1703)

- Nicola

Cleminson

(Anon.,

Germany c.

1750) - Jane

Debenham

(Saxony c.

1750) - Christel

Wiehe

(Rowland Ross,

1978) - Judith Falkus (Eberle,

Prague, 1733)

- Judith Garside (Nicholas

Woodward 1981

[Amati])

|

|

|

|

|

| Violas

|

Trevor Jones

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Jan

Schlapp (Antonius Bachmann, Berlin

1750 & Rowland Ross 1980 [Stradivarius])

- Katherine Hart (Rowland Ross 1980

& Charles and Samuel Thompson 1750) - Annette

Isserlis (Ian Clarke 1980 [Guarnieri])

- Nicholas Logie (Rowland Ross 1980)

- Colin Kitching (Rowland Ross 1978

[Stradivarius])

|

|

|

|

|

| Violoncellos

|

Mark Caudle

(David Rubio 1980 [D. Montagnana 1720]) - Richard

Webb (David Rubio 1975 [Januarius

Gagliano 1748]) - Susan Sheppard

(German c. 1700) - Timothy Mason

(Rowland Ross 1979 [Stradivarius]) - Juliet

Lehwalder (Jacob Haynes 1745) - Jane

Coe (David Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius

1732]) - Suki Towb (David

Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius 1732]) - Julie

Anne Sadie (David Rubio 1980

[Guardanini 1759])

|

|

|

|

|

| Double

Basses

|

Barry

Guy (The Tarisio, Gasparo da

Salo 1560) - Amanda McNamara

(Joseph Wagner 1773) - Keith

Marjoram (Anon., Italy c.1560)

- Anthony van Kampen

(Lorenzo & Tommaso Carcassi

1760) - Valerie Botwright

(Anon., Bavaria c.1780) |

|

|

|

|

Flutes

|

Stephen

Preston (Monzani c. 1800) - Lisa

Beznosiuk (William Henry

Potter c. 1800) - Guy Williams

(Monzani, circa 1825) |

|

|

|

|

| Oboes

|

Clare

Shanks (Milhouse, circa 1780)

- Robin Canter (H. Grenser

c. 1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Clarinets |

Keith

Puddy (Bodin, Paris c. 1790

& Moussetter, Paris c.1790) - Lesley

Schatzberger (Thomas Key,

London c. 1820 & Metzler, London

c.1812) |

|

|

|

|

Bassoons

|

Felix

Warnock (Savary jeune 1820) -

Alastair Mitchell (Clair

Godfroy c. 1810) - Hansjurg

Lange (Raymond Griesbacher

1765) - Julie Andrews (Astor

c. 1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Horns

|

William

Prince (Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Christian Rutherford

(Courtois neveu, circa 1800) - Colin

Horton (Courtois neveau c.

1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Trumpets

|

Michael

Laird (Laird 1977) - Iaan

Wilson (Laird 1977) - David

Staff (Staff 1979 [English

18th century]) |

|

|

|

|

| Timpani |

Stephen

Henderson (Cavalry type,

Anon., c. 1850) |

|

|

|

|

| Harpsichord

|

Christopher

Hogwood (Thomas Culliford,

London 1782) |

|

|

|

|

| Fortepiano |

Christopher

Hogwood (Adlam Burnett 1976

[Mathaeus Heilmann c. 1785) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kingsway

Hall, London (United Kingdom):

- novembre 1981 (K. 297 1 & 2

vers., 385, 504)

- febbraio 1982 (K. 551)

- marzo 1982 (K. 543, 550)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Morten

Winding / John Dunkerley |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - D171D4 (4 LP's) - durata

38' 29" | 62' 15" | 58' 12" | 37'

54" - (p) 1983 - Digitale

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 421 085-2 (3 CD's) - durata

70' 09" | 66' 26" | 53' 31" - (c)

1988 - DDD |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

and the symphonic

traditions of his

time by Neal

Zaslaw

Salzburg

and its Orchestra

When Mozart wrote an aria,

he tailor-made it to

exploit the strengths and

circumvent the weaknesses

of the singer for whom it

was destined. He usually

refused to compose an aria

until he was familiar with

the singer who was to

perform it, and when there

was a change in the cast

of an opera, he sometimes

inserted or substituted

new arias. In this he was

a man of his times, a

craftsman who sought to

please the singers, the

audience and himself with

wellwrought creations that

would make their intended

effect. Mozart’s concern -

one might even call it an

obsession - for providing

the right music for each

circumstance in which he

found himself is well

documented in his letters.

When he composed

symphonies, their style

was likewise influenced to

some degree by the

strengths and weaknesses

of a particular ensemble

and the tastes of a

certain audience.

It is for that reason that

this series of recordings

has for the first time

recreated the types of

ensemble for which Mozart

composed his symphonies,

enabling us to hear

differences between these

orchestras that Mozart and

his contemporaries thought

significant, and to learn

what influence those

differences may have had

upon the style of the

music. The ensembles range

from the tiny orchestras

that Mozart heard at

private concerts and small

courts to the large opera

orchestras that performed

his symphonies in Italy,

from the small but

accomplished Prague

orchestra that was so

devoted to Mozart and his

music to the

fifty-seven-member

orchestra of the Concert

spirituel, from string

sections whose balance was

similar to that of a

modern chamber orchestra

to string sections in

which the double basses

reatly outnumbered the

cellos and where there

were hardly any Violas.

Each of these

characteristic sounds may

be heard among the

more-than-sixty symphonies

in this collection.

Performance

Practice

The use of

18th-century instruments

with the proper techniques

of playing them gives to

the Academy of Ancient

Music a vibrant,

articulate sound. Inner

voices are clearly audible

without obscuring the

principal melodies. Subtle

differences in

articulation are heard

more distinctly than is

usually the case with

modern instruments. At

lively tempos and with

this luminous timbre, the

observance of all of

Mozart’s repeats does not

make movements seem too

long, and restores them to

their just proportions. A

special instance concerns

the da capos of the

minuets, where, the

written and oral

traditions of the ast

century-and-a-half tell

us, the repeats should be

omitted. But those

traditions cannot be

traced as far back as

Mozart’s time, and clues

found in writings

contemporaneous with him

suggest that repeats were

usually observed during da

capos.

Missing instruments

understood in 18th-century

practice to be required

have been supplied: these

include bassoons playing

the bass line with the

cellos and double basses

whenever obbligato bassoon

parts are not provided,

kettledrums whenever

trumpets are present, and

(with the exception of the

'Paris' symphony)

harpsichord or fortepiano

continuo. No conductor is

needed, as the direction

of the orchestra is

divided in true

18th-century fashion

between the concertmaster

and the continuo player,

who are placed so that

they can see each other

and are visible to the

rest of the orchestra. As

there was wide variation

in orchestral practice

from region to region in

western Europe, no

all-purpose classical

orchestra can be

recreated; rather, we have

attempted to present the

several kinds of ensembles

for which Mozart wrote,

whose peculiarities he had

in mind when composing.

Documentation of the

excellence of Viennese

orchestral playing in the

1770s and 80s is presented

in the notes to volume 7

of these recordings and

need not be repeated here.

As there was then no

single orchestra

dominating Viennese

musical life, we have for

Mozart’s Viennese

symphonies recreated a

typical orchestra,

avoiding the extremely

small groups that

sometimes performed at

private concerts as well

as the huge groups

occasionally assembled for

special occasions. For

example, the orchestras of

both the Kärntnerthor

and Burg Theatres in 1773

had 6 or 7 first and 6 or

7 second violins, 3 or 4

violas, 3 cellos and 3

double basses, with pairs

of the necessary wind and

brass, kettledrums and a

harpsichord. For Mozart’s

late symphonies, however,

fortepiano continuo has

been employed, on the

grounds that as Mozart sat

at that instument to lead

the orchestra and perform

the solo part in his piano

concertos, he probably did

the same for his

symphonies at those

concerts.

Musical Sources and

Editions

Until recently performers

of Mozart’s symphonies

have relied solely upon

editions drawn from the

old Complete Works,

published in the 19th

century by the Leipzig

firm of Breitkopf & Härtel.

During the past three

decades, however, a new

complete edition of

Mozart’s works (NMA)

has been appearing,

published by Bärenreiter

of Kassel in collaboration

with the Mozarteum of

Salzburg. The NMA

has been used for all the

works in this volume, with

revisions made to the

'Paris' and 'Prague'

symphonies as described

above.

The Final Trilogy

In the vast literature

about Mozart's life and

music, there are several

monographs, dozens of

articles, hundreds of book

chapters, and thousands of

programme notes devoted to

the last three symphonies

(K. 543, 550 and 551),

which were completed in 1788

in the space of about

three months. What one

gleans from reading a

generous sample of these

writings may be summarized

thus: we do not know for

what orchestra or what

occasion the three works

were composed, so they

were probably the result

of an inner artistic

compulsion rather than an

external stimulus; the

three works were intended

as a trilogy; these

masterpieces were never

performed during his

lifetime and this shows

how unappreciated he was

by his contemporaries. An

investigation of these

assertions shows two of

the three to be

misleading.

Anyone who has examined

the psychology of Mozart's

pace of composing knows

that, although he could

sometimes compose with

lightning speed, he was

also given to

procrastination, on

occasion he was depressed

and found it difficult to

compose, and he was often

painfully busy giving

lessons and concerts to

support his family. There

are plenty of documented

instances suggesting that

he seldom launched a

large-scale work

without a clear use for it

in mind, and that, when a

commission or opportunity

for performance or

publication dried up, he

would sometimes abandon a

work in mid-course. That

being the case, we should

be surprised if Mozart had

composed three large

symphonies with no

practical goals in mind,

and in this instance, we

can suggest three such

possible goals.

Perhaps the most immediate

goal in composing some if

not all of the three

symphonies was that Mozart

had scheduled a series of

subscription concerts for

June

and July

1788. It seems that only

the first of these

concerts actually took

place after which, owing

to an insufficient number

of subscribers, the rest

were cancelled. This was

to be the last time that

Mozart attempted to put on

a public concert in

Vienna.

Another goal is revealed

by the number three

itself. Sets of symphonies

were customarily sold in

manuscript or engraved

editions in groups of

three (for larger

symphonies) or in groups

of six (for smaller ones).

Mozart and his father had

prepared several sets of

six symphonies each

earlier in his career, and

in 1784 Mozart himself had

made up a set of three for

publication. We cannot

doubt that he hoped to

publish K. 543, 550 and

551 as an 'opus', although

in fact they remained

unpublished until after

his death.

The final goal was that in

1788 Mozart was trying to

arrange (and not for the

first time) a trip to

London. It

was well-known among

musicians on the Continent

that a talented

composer-performer could

make more money in London

than anywhere else, and -

as Haydn was to show by

his visits to London in

the early 1790s -

producing good symphonies

was an important element

in such a venture.

When the English tour

failed to materialize,

Mozart's three symphonies

provided music for a

German tour he made in

1789 to give concerts and

to seek patronage and

perhaps a permanent post.

An examination of what is

known of Mozart's

orchestral concerts on

this tour and of those

after his return to Vienna

undermines the notion that

the last three symphonies

remained unperformed

during his lifetime.

At the Dresden Court (14

April) Mozart performed a

piano concerto, and,

although the rest of his

programme is unknown, this

concert may very well have

also included at least one

symphony. A reaction to

this event survives, for

the Russian ambassador

attended Mozart's concert

and later summarized the

objections of some

contemporaries to the

composer - objections

which he himself

apparently did not share:

'Mozart is very learned,

very difficult,

consequently he is very

much esteemed by

instrumentalists; but he

seems never to have had

the good fortune to have

loved. No

modulation ever

issued from his heart.'

A copy of the programme of

Mozart's concert of 12 May

in the Leipzig Gewandhaus

survives. It

is reproduced below with

indications of the

probable identity of the

pieces.

Part I

Symphony

Scena. Mme. Duscheck (K.

505)

Concerto, on the

Pianoforte (K. 456)

Symphony

Part II

Concerto, on

the Pianoforte (K. 503)

Scena. Mme. Duscheck (K.

528)

Fantasy, on the Pianoforte

(K. 475)

Symphony

Although it would be

tempting to suppose that

Mozart's last three

symphonies were all

performed on this occasion

(raising interesting

questions about the

endurance of the orchestra

and the audience), it is

more likely that Mozart

followed the custom of

some of his Viennese

concerts, dividing a

symphony and using the

opening movements at the

beginning of the concert

and the finale at the end.

Thus Leipzig probably

heard only one, or perhaps

two, of the last

symphonies. The Leipzig

music critic Johann

Friedrich Rochlitz, who

met Mozart and attended

this concert and the

rehearsal for it, later

published a reminiscence

of the occasion in the Allgemeine

musikalische

Zeitung, of which he

was for many years the

editor:

'When I

went into the rehearsal

the next day... I

noticed to my

astonishment that the

first movement being

rehearsed - it was the

allegro of a symphony of

his - he took very, very

fast. Hardly twenty bars

had been played and - as

might easily be foreseen

- the orchestra started

to slow down and the

tempo dragged. Mozart

stopped, explained what

they were doing wrong,

cried out "Ancora", and

began again just as fast

as before. The result

was the same. He did

everything to maintain

the same tempo; once he

beat time so violently

with his foot that one

of his finely-worked

steel shoebuckles broke

into pieces: but all to

no avail. He laughed at

this mishap, left the

pieces lying there,

cried out "Ancora"

again, and started for

the third time at the

same tempo. The

musicians became

recalcitrant toward this

diminutive, deathly pale

little man who hustled

them in this way:

incensed, they continued

working at it, and now

it was all right.

Everything that

followed, he took at a

moderate pace. I must

admit: I thought then he

was rushing it a bit,

insisting he was right,

not through obstinacy

but in order not to

compromise his authority

with them right at the

beginning. But after the

rehearsal he said in an

aside to a few

connoisseurs: "Don’t be

surprised at me; it

wasn't caprice, but that

I saw that the majority

of the musicians were

already fairly old

people. The dragging

would never have stopped

if I hadn't first driven

them to their limit and

made them angry. Now

they did their best

through sheer

irritation". As Mozart

had never before heard

this orchestra play,

that shows a fair

knowledge of human

nature; so he was not

after all a child in

everything outside of

the realm of music - as

people so often say and

write.'

One would

dearly love to believe

this amusing anecdote, if

only Rochlitz didn't have

such a terrible reputation

for publishing trumped-up

documents.

In 1790 Mozart, still

searching pathetically for

patronage and a suitable

post, travelled to

Frankfurt at his own

expense to be present at

the festivities

surrounding the coronation

of Leopold II. A concert

he gave there on 15

October is documented by

the fullest eye-witness

account of any such event

that we possess, written

by Count Ludwig von

Bentheim-Steinfurt in his

diary:

'At 11 o'clock in the

morning there was a grand

concert by Mozart

in the auditorium of the

National Playhouse. It

began with the fine (1) Symphony

by Mozart which I have

long possessed. (2) Then

came a superb Italian

aria, "Non so di chi”,

which Madame Schick

sang with infinite

expressiveness. (3) Mozart

played a Concerto

composed by him which was

of an extraordinary

prettiness and charm;

he had a fortepiano by

Stein of Augsburg which

must be supreme of its

kind and costs from 90 to

100 pounds. Mozart's

playing is a little like

that of the late Klöffler,

but infinitely more

perfect. Monsieur Mozart

is a small man of rather

pleasant appearance; he

had a coat of brown marine

satin nicely embroidered;

he is engaged at the

Imperial Court. (4) The

soprano Cecarelli

sang a beautiful scena and

rondeau, for bravura airs

do not appear to be his

forte; he had grace and a

perfect method; an

excellent singer but his

tone is a little on the

decline, that and his ugly

physiognomy; for the rest

his passage work,

ornaments and trills are

admirable...

In

the second act, (5)

another concerto by

Mozart, which however did

not please me like the

first. (6) A duet which we

possess and I recognized

by the passage "Per te,

per te", with ascending

notes... It was a real

pleasure to hear these two

people, although La

Schick lost by

comparison with the

soprano in the matter of

voice and ornaments, but

she scored in the passage

work at least. (7) A

Fantasy without the

music by Mozart,

very charming, in

which he shone

infinitely, exhibiting

all the power of his

talent. (8) The last

symphony was not given for

it was almost two o'clock

and everybody was sighing

for dinner. The music thus

lasted three hours, which

was owing to the fact that

between the pieces there

were very long pauses. The

orchestra was no more than

rather weak with five or

six violins, but apart

from that very acccurate.

There was only one

accursed thing that

displeased me very much:

there were not many

people...'

During Mozart's last years

in Vienna, his concert

activities were much

reduced compared to those

in the early 1780s, and we

are poorly informed about

these concerts because,

Mozart's father having

died, we do not have a

series of informative

letters. In fact, the only

documented occasion on

which a symphony was

performed took place on 16

and 17 April 1791 at the

'Society of Musicians'

annual benefit concert,

when a large orchestra

under the direction of

Antonio Salieri performed

a 'grand symphony’ by

Mozart. As Mozart's

friends the clarinettists

Johann

and Anton Stadler were in

the orchestra, the

symphony played may have

been either K. 543 or the

second version of K. 550.

The very existence of

versions of K.550 with and

without clarinets

demonstrates that the work

was performed, for Mozart

would hardly have gone to

the trouble of adding the

clarinets and rewriting

the flute and oboes to

accommodate them, had he

not had a specific

performance in view. And

the version without

clarinets must also have

been performed, for surely

the re-orchestrated

version, which exists in

Mozart's hand, of two

passages in the slow

movement can only have

resulted from his having

heard the work and

discovered an aspect

needing improvement. Even

though the alternative

version of the two

passages in the Andante

must represent Mozart's

final thoughts, it is

missing from most editions

of the symphony and

relegated to an appendix

in the NMA. But

because it gives every

sign of being the

definitive version, we

have used it for this

recording of the version

of K. 550 without

clarinets.

If we add to the concert

activities documented

above the evidence of

surviving contemporaneous

sets of manuscript parts

of the last three

symphonies, we can

confidently lay to rest

the myth that these works

remained unperformed

during his lifetime.

Symphony in Eb major,

K.543

The autograph manuscript,

also in Kraków,

bears no inscription at

all, but in Mozart's

catalogue of his own works

it is dated 'Vienna, 26

Iune 1788'. This symphony

is the least well known

and performed of the last

six symphonies. As K. 543

exhibits no lack of fine

workmanship or first-rate

inspiration, we must

speculate on the possible

reasons for its relative

neglect. Could it be due

to the fact that the other

late symphonies have

nicknames to characterize

them in the minds of

conductors and audiences,

while the Eb major symphony

does not? Could it be that

the kinds of ideas

Mozart chose to explore in

this work survive the

translation from the lean,

clear sound of

18th-century instruments

to the powerful, opaque

sounds of modern

instruments less well than

do the more muscular,

proto-Romantic ideas of

the 'Great G-minor’ and ’Jupiter'

symphonies? Could it be

that the flat key, which

yields a relatively muted

sound compared to the

brilliance of C major (K.

425, 551) and D major (K.

504), makes less of an

impression in large modern

halls on 20th-century

instruments than it did in

small 18th-century halls

with period instruments?

This recording has as one

of its goals to provide a

living laboratory to seek

answers to such questions,

and each listener must

judge for himself what the

results of the experiment

may be.

It has been suggested that

K. 543 was consciously

modelled on Michael

Haydn's Eb major

symfphony, Perger no. 17,

a work which Mozart in act

acquired in 1784. If so,

Mozart so far surpassed

his 'model' as to make

comparison virtually

meaningless. More likely

is the influence of the

symphonies of brother Joseph

Haydn, noticeable

especially in the stately

slow introduction to the

first movement and the

serene Andante con moto.

The first allegro is an

interesting case of strong

ideas presented in a

deliberately understated

way. The courtly minuet is

set off by a trio based on

an Austrian ländler,

given out by a favourite

Alpine village instrument,

the clarinet, complete

with oom-pah-pah

accompaniment. The

perpetual motion of the

finale exhibits a great

deal of the kind

of mischievous good humour

for which Joseph

Haydn's finales are

famous.

Symphony in G minor,

K.550 ('Great’, First

Version)

The autograph manuscripts

of both versions of this

work (as well as a

corrigenda leaf discussed

above) are found in the

Gesellschaft der

Musikfreunde in Vienna,

given to that institution

by Brahms. K. 550, was

probably dubbed ’the

Great' to distinguish it

from the 'Little G-minor’

symphony, K. 173dB/183,

itself an extraordinary

work. As the 'Great

G-minor' symphony was

first published in 1794

and the 'Little G-minor’

in 1798, the pair of

nicknames must have arisen

in the 19th-century. That

the designation 'Great'

stuck to K. 550 was

probably due to the other

meaning of the word -that

is, 'magnificent,

outstanding, remarkable'

and not simply 'large' -

for of all of Mozart's

symphonies this was the

one that most interested

the musicians and critics

of succeeding generations.

The work’s intensity,

unconventionality

chromaticism, thematic

working-out, profusion of

ideas - all of these

endeared it to the

Romantics. Nonetheless,

there was no agreement

about its meaning, for

some found it imbued with

tragedy (even with

premonitions of Mozart's

early death) while others

thought it had the

classical balance,

proportions and repose of

a Greek vase.

There were of course those

who understood the work

immediately; for instance,

Joseph

Haydn, who quoted from its

Eb-major slow movement in

his oratorio The

Seasons in the

Eb-major aria, no. 38,

where winter is compared

to old age. The quotation

occurs following the words

'...exhausted is thy

summer's strength...'

by which Haydn

simultaneously offers us

an interpretation of

Mozart's music,

commemorates the loss of

his younger colleague, and

perhaps also comments upon

the approaching end of his

own career. Schubert also

took note of K. 550,

basing the minuet of his

Fifth Symphony on its

minuet.

It was largely Richard

Wagner's towering

influence as a conductor

of Beethoven’s symphonies

that changed the way in

which works like K. 550

were performed. In the

19th-century the size of

both string and wind

sections was gradually

increased, to match the

increase in the size of

concert halls and opera

houses. These enlarged

string sections tended to

be too powerful when the

wind were reduced to

Mozart's smaller forces. In

addition, the playing

style and the way in which

instruments were being

built (or, in the case of

string instruments, also

rebuilt) had gradually

come to favour legato

playing rather than

detached playing - the

performance-practice

equivalent of unendliche

Melodie. Finally,

with the rise of virtuoso

orchestral conductors -

and here Wagner's example

was most influential - the

tempo of a movement was

understood to be in a

state of continual flux.

Indeed, this continuous

moulding of the tempo

during performance came

eventually to be one of

the principal points by

which a conductors

interpretation was judged.

The present performances

do away with these

encrustations of Romantic

tradition and approach the

symphonies from a more

objective, 18th-century

point of view.

Symphony in C major,

K.551 ('Jupiter')

Like so many other

precious Mozart

autographs, the manuscript

of K. 551 is in the

material formerly in

Berlin and now at Kraków.

On the autograph Mozart wrote

only 'Sinfonia', while a

later hand added '10

Aug. 1788', taken

undoubtedly from the entry

in Mozart's catalogue,

which reads 'Vienna, 10

August 1788'.

The work’s nickname, 'Jupiter',

seems to have originated

in London. Mozart's son

W.A. Mozart fils,

told Vincent and Mary

Novello that the sobriquet

was coined by Haydn's

London sponsor, the

violinist and orchestra

leader Johann

Peter Salomon. And indeed

the earliest edition of

the work to employ the

subtitle 'Jupiter'

was a piano arrangement

made and published by

Muzio Clementi in London

in 1823. During the first

half of the 19th-century

in the German-speaking

world, however, K. 551 was

known as 'the symphony

with the fuga finale'.

The designation 'Jupiter’

was probably inspired by

the pomp of the first

movement which, with its

prominent use of trumpets

and kettledrums and

stately dotted rhythms,

was calculated to evoke

images of nobility and

godliness in the

18th-century mind.

The Andante cantabile,

with its muted violins and

subdominant key, turns 180

degrees from the lighter

realms of the first

movement

toward a darker

region. The minuet and

trio hide beneath their

politely galant exteriors

a host of contrapuntal and

motivic artifices, which

impart to the pair an

exceptional unity. And the

famous fugal finale?

Modern theorists, raised

on Bach fugues, will tell

you that it is not a fugue

at all, but their

definition of the genre is

certainly not that of the

late 18th- and early

19th-centuries. The

movement is, to be sure,

in sonata form with both

repeats and a vast coda in

which occurs one of the

great miracles of Western

music: a triumphal fugato

in which the main melodic

ideas of the movement are

brought together in

various combinations and

permutations in invertible

counterpoint, in a way

that has everything to do

with the summation and

conclusion of a dynamic

symphonic movement and

nothing at all to do with

dry lessons in

counterpoint. Joseph

Haydn, perhaps the only

contemporary of Mozart's

able fully to comprehend

him during his lifetime,

paid this work the

ultimate compliment of

quoting from its slow

movement in the slow

movement of his Symphony

no. 98, and of modelling

the finale of his Symphony

no. 95 on that of the

'Jupiter'.

A Note Concerning the

Numbering of Mozart's

Symphonies

The first

edition of Ludwig Ritter

von Köchel's

Chronological-Thematic

Catalogue of the

Complete Works of

Wolfgang Amaadé

Mozart was published

in 1862 (=K1).

It

listed all of the

completed works of Mozart

known to Köchel

in what he believed to be

their chronological order,

from number 1 (infant

harpsichord work) to 626

(the Requiem). The second

edition by Paul Graf von

Waldersee in 1905 involved

primarily minor

corrections and

clarifications. A

thoroughgoing revision

came first with Alfred

Einstein's third edition,

published

in 1936 (=K3).

(A reprint of this edition

with a sizeable supplement

of further corrections and

additions was published in

1946 and is sometimes

referred to as K3a.)

Einstein changed the

position of many works in

Köchel's

chronology, threw out as

spurious some works Köchel

had taken to be authentic,

and inserted as authentic

some works Köchel

believed spurious or did

not know about. He also

inserted into the

chronological scheme

incomplete works,

sketches, and works known

to have existed but now

lost. These Köchel

had

placed in an appendix (=Anhang,

abbreviated Anh.)

without chronological

order. Köchel's

original numbers could not

be changed, for they

formed the basis of

cataloguing for thousands

of publishers, libraries,

and reference works.

Therefore, the new numbers

were inserted in

chronological order

between the old ones by

adding lower-case letters.

The so-called fourth and

fifth editions were

nothing more than

unchanged reprints of the

1936 edition, without the

1946 supplement. The sixth

edition, which appeared in

1964 and was edited by

Franz Giegling, Alexander

Weinmann, and Gerd Sievers

(=K6),

continued Einstein's

innovations by adding

numbers with lower-case

letters appended, and a

few with upper-case

letters in instances in

which a work had to be

inserted into the

chronology between two of

Einstein's lowercase

insertions. (A so-called

seventh edition is an

unchanged reprint of the

sixth). Hence, many of

Mozart's works bear two K

numbers, and a few have

three.

Although it was not Köchel's

intention in devising his

catalogue, Mozart's age at

the time of composition of

a work may be calculated

with some degree of

accuracy from the K

number. (This works,

however, only for numbers

over 100). This is done by

dividing the number by 25

and adding 10. Then, if

one keeps in mind that

Mozart was born in 1756,

the year of composition is

also readily approximated.

The old Complete Works of

Mozart published 41

symphonies in 3 volumes

between 1879 and 1882,

numbered 1 to 41 according

to the chronology of K1.

Additional symphonies

appeared in supplementary

volumes and are sometimes

numbered 42 to 50,

even though they are early

works.

©

1983

Neal Zaslaw

Bibiography

- Anderson,

Emily: The Letters

of Mozart & His

Family (London,

1966)

- Burney,

Charles: The

Present State of

Music in Germany,

The Netherlands, and

United Provinces

(London, 1773)

- Della

Croce, Luigi: Le

75 sinfonie de

Mozart (Turin,

1977)

- Eibl,

Joseph Heinze, et al.:

Mozart: Briefe und

Aufzeichnungen

(Kassel, 1962-75)

- Koch,

Heinrich: Musilcalisches

Lexikon

(Frankfort, 1802)

- Landon,

H. C. Robbins: 'La

crise romantique dans

la musique

autrichienne vers

1770: quelques

précurseurs inconnus

de la Symphonie en sol

mineur (KV 183) de

Mozart', Les

influences étrangères

dans l'oeuvre de W.

A. Mozart

(Paris, 1958)

- Larsen,

Jens

Peter: 'A Challenge to

Musicology: the

Viennese Classical

School', Current

Musicology

(1969), ix

- Mahling,

Christoph-Hellmut:

'Mozart und die

Orchesterpraxis seiner

Zeit', Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1967)

- Mila,

Massimo: Le

Sinfonie de Mozart

(Turin, 1967)

- Saint-Foix,

Georges de: Les

Symphonies de Mozart

(Paris, 1932)

- Schneider,

Otto, and Anton

Algatzy: Mozart-Handbuch

(Vienna, 1962)

- Schubart,

Ludwig: Christ, Fried.

Dan. Schubart's

Ideen zu einer

Asthetik der

Tonkunst

(Vienna, 1806)

- Schultz,

Detlef: Mozarts Jugendsinfonien

(Leipzig, 1900)

- Sulzer,

Johann

Georg: Allgemeine

Theorie der schönen

Künste

(Berlin, 1771-74)

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'The Compleat

Orchestral Musician',

Early Music

(1979), vii/1

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'Toward the

Revival of the

Classical Orchestra',

Proceedings of the

Royal Musical

Association

(1976-77), ciii

|

|

Symphony

in D major, K.300a/297

(’Paris’)

Despite an extensive

literature about

Mozart’s stay in Paris

in 1778, many questions

remain concerning his

activities there.

The twenty-two-year-old

composer and his mother

arrived in the French

capital on 23 March of

that year, in search of

a position worthier of

his talents than that

which he had held at

Salzburg. His time in

Paris was to prove a

disaster; not only did

Mozart fail to find

regular employment, to

make much money by his

freelance activities or

to produce many

compositions, but his

mother died.

By common report, the

best orchestra in Paris

in 1778 was not the

orchestra of the

wellestablished Concert

spirituel, but rather

that of the newer

Concert des amateurs,

founded in 1769 by

Gossec. The Concert des

amateurs flourished

until January

1781, when one of its

principal patrons

withdrew his support,

ending the series

abruptly, apparently

much to the regret of

everyone involved.

Performances were held

at the Hôtel

de Soubise two or three

times a week in the

autumn and the spring.

In order best to present

his symphonies to the

Parisian public, Mozart

should have approached

the director of the

Concert des amateurs (in

1778 the violinist and

composer Joseph

Boulogne, le chevalier

de Saint-Georges). An he

probably had some such

plan in mind, for in a

letter written to his

father from Mannheim on

3 December 1777 he

reported hearing from

musicians there (who

would have been in a

position to know, as

several Mannheim

composers had had

symphonies published and

performed in Paris) that

the Concert des amateurs

paid five louis d’or

for a new symphony. In

the event, however,

Mozart was introduced to

Joseph

Le Gros, director of the

Concert spirituel, and

it was for that

organization that he

composed a symphony.

The history of this work

is documented in

Mozart’s letters. It is

the well-known Symphony

in D major, K.300a/297,

the so-called 'Paris'

symphony, which Mozart

must have completed - at

least in his head if not

necessarily on paper -

by 12 June, on

which date he wrote to

his father reporting

that earlier in the day

he had played through it

at the keyboard for the

singer Anton Raaff and

Count Sickingen,

minister of the

Palatinate, after lunch

at the latter’s house.

The symphony had its

première at

the Concert spirituel on

Corpus Christi (18 June)

after only one rehearsal

- the usual 18th-century

practice - on the

previous day. Mozart

reported (3 July):

I

was very nervous at

the rehearsal, for

never in my life

have I heard a worse

performance; you

cannot imagine how

they twice bumbled

and scraped through

it. I was really in

a terrible state and

would gladly have

rehearsed it again,

but as there is

always so much to

rehearse there was

no time left. So I had

to go to bed with an

anxious heart and in

a discontented and

angry frame of mind.

Next day I had

decided not to go to

the concert at all;

but in the evening,

the weather being

fine, I at last made

up my mind to go,

determined that if

[my symphony] went

as badly as it had

at the rehearsal I

would certainly go

up to the orchestra,

take the violin from

the hands of

Lahoussaye, the

first violinist, and

lead myself! I

prayed to God that

it might go well,

for it is all to His

greater honour and

glory; and behold,

the symphony

began... Right in

the middle of

the first Allegro

was a passage that I

knew they would

like; the whole

audience was

thrilled by it and

there was a

tremendous burst of

applause; but as I

knew, when I wrote

it, what kind of an

effect it would

produce, I repeated

it again at the end

- when there were

shouts of 'Da Capo'.

The Andante also

found favour, but

particularly the

last Allegro

because, having

observed that here

all final as well as

first Allegros begin

with all the

instruments playing

together and

generally unisono, I

began mine with the

two violin-sections

only, piano for the

first eight bars -

followed instantly

by a forte; the

audience, as I

expected, said

"Shh!" at the soft

beginning, and as

soon as they heard

the forte which

followed immediately

began to clap their

hands. I was so

happy that as soon

as the symphony was

over I went off to

the Palais Royal

where I had a large

ice, said the rosary

as I had vowed to do

- and went home.

There was

a single, brief review

of the concert, stating

of Mozart only that

'This artist, who from

the tenderest age had

made a name for himself

among harpsichordists,

can today be placed

among the ablest

composers’.

Mozart’s description of

the orchestra of the

Concert spirituel can be

supplemented from other

sources. In the period

between Mozart’s

previous visits to Paris

(1763-64 and 1766) and

the visit which concerns

us here, the orchestra

of the Concert spirituel

went through a series of

reforms, undoubtedl

occasioned by the fact

that the orchestra had

been formed in 1725 to

perform a repertory of

French music in the

style of Delalande,

whose motets were

mainstays of their

concerts. Gradually

the Concert spirituel

came to perform less

French and more

Italian and German

music, less archaic

and more modern music,

to which new tasks it

was at first

ill suited. The

orchestral reforms

were also surely

motivated by invidious

comparisons with the

Concert des amateurs,

whose orchestra was

from the start

designed to perform

'modern' music. In

March 1777 there was

the latest of many

changes of management

at the Concert

spirituel: following

the death of Leduc,

Gaviniès

and Gossec resigned as

directors, Le Gros was

appointed to replace

them, and the

membership of the

orchestra was once

again reformed.

According to the Almanack

des spectacles de

Paris for 1779,

the composition of the

orchestra that gave

the première

of Mozart’s K.300a/297

on 18 ]une 1778 was 11

first and 11 second

violinists, 5

violists, 8 cellists,

5 double bass players,

6 men who played

flute, oboe and

clarinet, 4

bassoonists, 6 men who

played horn and

trumpet, and 1

timpanist, or a total

of fifty-seven

musicians. This

orchestra has been

precisely duplicated

for the present

recording. We do not

know the seating plan

used by the orchestra

of the Concert

spirituel, but as the

orchestra had been

reformed several times

in imitation of that

of the Concert des

amateurs, we have

obeyed the advice

recorded by the

violinist J.J.O.

de Meude-Monpas, based

upon his experience

with the latter

organization:

'The

orchestra's

disposition counts

for much, and one

must observe the

following rules,

namely: put the

second violins

opposite and not

alongside the

firsts; place the

bass instruments

as near as

possible to the

first violins (for

in harmony the

bass is the

essential part of

the chords);

finally, bring

together the wind

instruments, such

as the oboes,

flutes, horns,

etc; and finish it

off with the

Violas.'

Certain

aspects of this

orchestra deserve

comment: one is the

large number of

bassoons, a feature of

several orchestras of

the period, which

gives the bass line a

characteristic

'etched' sound quite

different from that of

a modern orchestra's

bass line. Because the

upper woodwind were

double-handed, it was

possible to play

French motets,

ouvertures and dances

with three first and

three second oboes, or

to play works with

'modern'

orchestration, like

Mozart’s symphony,

with pairs of flutes,

oboes and clarinets.

Another noteworthy

feature is the

apparent absence of a

keyboard continuo

player. The roster of

the orchestra of the

Concert spirituel

contained an organist

up to and including

the 1772-73 season,

after which no

keyboard player was

listed. One notices

among the directors in

the 1770s and 80s,

however, persons

qualified to play

keyboard continuo.

Works containing

recitative continued

to appear on the

programmes of the

Concert spirituel, and

we must therefore

suppose that someone

was available to play

continuo for such

works even if a newer

practice may have

eliminated the

continuo instrument

for most or even all

other types of music.

(The 'Paris' symphony

is performed here

without continuo.)

Finally, all evidence

suggests that when

German or Italian

orchestras of the

period had string

sections this large,

the wind would nearly

always have been

doubled. The sound of

our recreated 'Paris'

orchestra (in which

only the bassoons and

horns are doubled) is

the most

string-dominated and

hence the most like

that of a modern

orchestra of all those

recreated for this

series of recordings.

Following the

performance of his symphony,

Mozart fell out with

Le Gros, due to the latter’s

failure to arrange for

a performance of

Mozart’s Sinfonia

concertante,

K.297B/A9. On 9 July,

however, the two men

had a chance encounter

at which, as Mozart

reported to his father

on that very day, Le

Gros commissioned

another symphony and

gave Mozart his

opinion of K.300a/297:

'...the

symphony was

highly approved of

- and Le Gros is

so pleased with it

that he says it is

his very best

symphony. But the

Andante has not

had the good

fortune to satisfy

him: he says that

it has too many

modulations and

that it is too

long. He derives

this opinion,

however, from the

fact that the

audience forgot to

clap their hands

as loudly and as

long as they did

at the end of the

first and last

movements. For

indeed the Andante

has won the

greatest approval

from me, from all

connoisseurs,

music-lovers and

the majority of

those who have

heard it. It is

just the reverse

of what Le Gros

says -for it is

quite simple and

short. But in

order to satisfy

him (and, as he

maintains, several

others) I have

composed another

Andante. Each is

good in its own

way - for each has

a different

character. But the

new one pleases me

even more... On

August 15th, the

Feast of the

Assumption, my

symphony is to be

performed for the

second time - with

the new Andante.'

And, in

fact, not only is the

performance of a

Mozart symphony at the

Concert spirituel on

15 August 1778

confirmed by notices

in the Parisian

newspapers, but there

is indeed a second

andante for

K.300a/297, for the

Berlin manuscript

contains one slow

movement while the

Parisian first edition

has an entirely

different one (see

illustrations). There

seems to be general

agreement today as to

which was the original

slow movement and

which the movement

written to replace it.

The latest edition of

the Köchel

Catalogue states the

matter as though it

were beyond doubt:

'The Andantino is the

original version's

middle movement; the

middle movement

(Andante) subsequently

performed in Paris is

found only in the

first edition’. By the

'Andantino’ the

editors of K6 meant

the movement in 6/8

metre consisting of 98

bars (called

’Andantino’ in a draft

but 'Andante'

in the final score);

the movement found in

the first edition is

in 3/4 metre and

consists of 58 bars.

To avoid the

possibility of

confusion, we shall

refer to them by their

metres. The view

stated in K6 that the

3/4 movement is the

later of the two has

been held by several

reputable Mozart

scholars in recent

years: for instance,

by Hermann Beck, Otto

Erich Deutsch, and J.H.

Eibl. It is also to be

found in Alfred

Einstein’s 1947

Supplement to K3, and

was perhaps first

voiced) by

Georges de Saint-Foix

in 1936. On the other

hand, at the time of

K3 Einstein thought

that the two movements

were the other way

round, following the

opinion found in the

first two editions of

that venerable

catalogue and also

held by E.H. Mueller

von Asow and Hans F.

Redlich. In fact,

recent research by

Alan Tyson (see

bibliography) strongly

supports the notion

that the 3/4 movement

was the original and

the 6/8 movement the

substitute.

There are three modern

editions of the

'Paris' symphony which

contain the 3/4

andante movement.

Anyone who takes the

trouble to compare

these editions will

notice that the solo

bassoon part differs

from edition to

edition as well as

from the one heard on

this recording.

These discrepancies

exist because the sets

of engraved orchestral

parts of the first

edition (which provide

the only source of this

movement) surviving in

various libraries lack

their bassoon parts; the

editors of the three

editions were forced

therefore to supply a

conjectural bassoon part

based on incomplete cues

in the cello part.

Fortunately, however,

another copy of the

first edition, which

includes the hitherto

missing bassoon part, is

in the private library

of Alan Tyson, who has

generously made it

available, thus enabling

this graceful movement

to be heard, for the

first time in the 20th

century, as Mozart wrote

it.

Although the finales of

the 'Paris' symphony are

nearly identical in the

printed editions and in

the autograph manuscript

(in which the finale has

been provided in the

hand of a copyist,

unlike the other two

movements which are in

Mozart’s own hand), the

first movements of the

manuscript and of the

printed editions differ

in a number of details

of dynamics, phrasing,

and voicing of chords,

and both versions have

therefore been recorded

here.

K.300a/297 was the first

of Mozart’s symphonies

to employ clarinets, an

instrument for which he

had great affection, but

which was found in few

orchestras in the 1770s.

When in Mannheim he had

written to his father

(with the Salzburg

orchestra in mind), 'Ah,

if only we too had

clarinets! You cannot

imagine the glorious

effect of a symphony

with flutes, oboes, and

clarinets'.

In Paris Mozart had his

chance, yet the writing

for the clarinets is

conservative, as if he

perhaps did not quite

trust the players on

whom he had to depend.

Since Le Gros apparently

commissioned another

symphony and since

Mozart in a letter of 3

October 1778 mentioned

'2 ouverturen’, there

have been several

attempts to sort out the

identity of this

apparently lost second

'Paris' symphony. A

number has even been

assigned to it in the Köchel

Catalogue (K. 311A/A8),

and the almost certainly

spurious Ouverture in Bb

major, K. AC11.05/311a,

has been proposed. I am

convinced, however, that

the socalled 'second

Paris symphony' was

merely an earlier work

that Mozart took with

him from Salzburg (see

my article on the Paris

symphonies listed in the

bibliography). That

Mozart had symphonies

from Salzburg with him

on his trip is clearly

documented in several

letters prior to his

arrival in Paris, and on

the eve of his departure

from the French capital,

when he was trying to

sell quickly a number of

pieces to publishers in

order to raise cash for

his journey home, he

wrote (11

September), 'As for the

symphonies, most of them

are not to the Parisian

taste’, in order to

explain to his father

why they could not be

sold.

And what did Mozart and

his father think the

Parisian taste in

symphonies to be?

According to Leopold (29

]une 1778):

'To

judge by the Stamitz

symphonies which

have been engraved

in Paris, the

Parisians must be

fond of noisy music.

For these are

nothing but noise.

Apart from this they

are a hodge-podge,

with here and there

a good idea, but

introduced very

awkwardly and in

quite the wrong

place.'

And Mozart

wrote of his 'Paris'

symphony K.300a/297:

'I

have been careful

not to neglect le

premier coup d'archet

- and that is quite

sufficient. What a

fuss the oxen here

make of this trick!

The devil take me if

I

can see any

difference! They all

begin together, just

as they do in other

places.'

If we add

to orchestral 'noises'

and le premier coup

d'archet Mozart’s

remark that 'all last as

well as first Allegros

begin here with 'all

instruments playing

together and generally unisono,'

we

have the the Mozarts'

impression of Parisian

taste in symphonies in

1778. To this we might

add a preference for

major keys and for three

rather than four

movements (that is,

omitting the minuet).

Mozart’s K.300a/297 fits

this composite

description, with the

exception (which he

himself noted) of the

way in which the finale

begins.

Furthermore, it has been

plausibly suggested by

Robert Münster

that Mozart had not only

a good general idea of

what would please

Parisian audiences, but

perhaps also a specific

model, namely, a D-major

symphony (Riemann no.

D-11) by the Mannheim

composer Carl Joseph

Toeschi, which had

enjoyed great success in

Paris a few years

earlier. Mozart arrived

in Paris fresh from

hearing the brilliant

Mannheim orchestra and

filled with tales of the

successes that Mannheim

composers had had in

Paris - successes he

hoped to reproduce for

himself. His use of a

model in such

circumstances should not

be surprising. Asside

from sharing the same

key and general movement

structure, the Paris

symphonies of Mozart and

Toeschi exhibit another

striking similarity: the

exceptionally frequent

repetition of musical

phrases. No other

symphony of Mozart’s has

this feature to such a

degree.

Symphony in D major,

K.385 ('Haffner’,

Second Version)

The circumstances

surrounding the creation

of this work are more

fully documented than

those for any other of

Mozart’s symphonies. In

mid-July

1782 Mozart’s father

wrote to him in Vienna

requesting a new

symphony for

celebrations surrounding

the ennoblement of

Mozart’s childhood

friend Siegmund Haffner

the younger. On 20 Iuly

Mozart replied:

'Well,

I am up to my eyes

in work. By Sunday

week I have to

arrange my opera [The

Abduction from the

Seraglio, K. 384]

for wind

instruments,

otherwise someone

will beat me to it

and secure the

profits instead of

me. And now you ask

me to write a new

symphony too! How on

earth can I do so?

You have no idea how

difficult it is to

arrange a work of

this kind for wind

instruments, so that

it suits them and

yet loses none of

its effect. Well, I

must just spend the

night over it, for

that is the only

way; and to you,

dearest father, I

sacrifice it. You

may rely on having

something from me by

every post. I shall

work as fast as

possible and, as far

as haste permits, I

shall write

something good.'

Although

Mozart was prone to

procrastination and to

making excuses to his

father, in this instance

his complaints may well

have been justified, for

having just completed

the arduous task of

launching his new opera

(the première

was on 16 July),

Mozart moved house on 23

July

in preparation for his

marriage. By 27 July

he reported to his

father:

'You

will be surprised

and disappointed to

find that this

contains only the

first Allegro; but

it has been quite

impossible to do

more for you, for I

have had to compose

in a great hurry a

serenade [probably

K. 375], but for

wind instruments

only (otherwise I

could have used it

for you

too). On Wednesday

the 31st I shall

send the two

minuets, the Andante

and the last

movement. If I can

manage to do so, I

shall send a march

too. If not, you

will just have to

use the one from the

Haffner music [K.

249], which is quite

unknown. I have

composed my symphony

in D major, because

you prefer that key.'

On 29 ]uly

Siegmund Haffner the

younger was ennobled and

added to his name 'von

Imbachhausen'. On the

31st, however, Mozart

could still only write:

'You

see that my

intentions are good

- only what one

cannot do, one

cannot! I Won't

scribble off

inferior stuff. So I

cannot send you the

whole

symphony until next

postday. I could

have let you have

the last movement,

but I prefer to

despatch it all

together, for then

it will cost only

one fee. What I have

sent you has already

cost me three

gulden.'

On 4

August Mozart and

Constanze Weber were

married in Vienna

without having received

Leopold’s approval,

which arrived grudgingly

the following day. In

the meanwhile the other

movements must have been

completed and sent off,

for on 7 August Mozart

wrote to his father:

'I

send you herewith a

short march

[probably K. 408,

no. 2]. I only hope

that all will reach

you in good time,

and be to your

taste. The first

Allegro must be

played with great

fire, the

last- as fast

as possible.'

Precisely

when the party

celebrating Haffner’s

ennoblement occurred,

and whether the new

symphony was received in

time to be performed on

that occasion, is not

known, for Leopold's

letter reporting the

event is lost. The fact

that in a later letter

Wolfgang was unsure

whether or not

orchestral parts had

been copied (see below)

suggests that the

symphony had not arrived

in time. Be that as it

may, at some time prior

to 24 August, Leopold

must have written his

approval of the work,

for on that day Wolfgang

responded, 'I am

delighted that the

symphony is to your

taste’.

Three months later the

symphony again entered

Mozart's correspondence.

On 4 December he wrote

to his father, in a

letter that went astray,

asking for the score of

the symphony to be

returned. When it had

become clear that his

father had not received

that letter, he wrote

again on the 21st,

summarizing the lost

letter, including, 'If

you find an opportunity,

you might have the

goodness to send me the

new symphony that

I composed for Haffner

at your request. Please

make sure that I

have it before Lent,

because I would very

much like to perform it

at my concert’. On 4 January

he again urged his

father to retum the

symphony, stating that

either the score or the

parts would be equally

useful for his purposes.

On the 22nd he again

reminded his father, and

on the 5th of February

yet again with new

urgency; ’...as soon as

possible, for my concert

is to take place on the

third Sunday in Lent,

that is, on March 23rd,

and I must have several

copies made. I think,

therefore, that if it is

not copied [into

orchestral parts]

already, it would be

better to send me back

the original score just

as I sent it to you; and

remember to put in the

minuets'. The usually

punctilious Leopold's

delay is mute testimony

to the anger and

frustration he felt over

what he considered to be

his son’s foolish choice

of a wife. In any case,

by 15 February Wolfgang

could write, 'Most

heartfelt thanks for the

music you have sent

me... My new Haffner

symphony has positively

amazed me, for I had

forgotten every single

note of it. It must

surely produce a good

effect'.

Mozart then proceeded to

rework the score sent

from Salzburg by putting

aside the march,

eliminating one of the minuets,

deleting the repeats of

the two sections of the

first movement, and

adding pairs of flutes

and clarinets in the

first and last

movements, primarily to

reinforce the tuttis and

requiring no change in

the existing

orchestration of those

movements.

The 'academy' (as

concerts were then

called) duly took place

on Sunday, 23 March, in

the Burg Theatre. Mozart

reported to his father:

'...the

theatre could not

have been more

crowded and... every

box was taken. But

what pleased me most

of all was that His

Majesty the Emperor

was present and,

goodness! - how

delighted he was and

how he applauded me!

It is his custom to

send money to the

box office before

going to the

theatre; otherwise I

should have been

fully justified in

counting on a larger

sum, for really his

delight was beyond

all bounds. He sent

25 ducats.’

In its

broad outlines, Mozart’s

report is confirmed by a

review of the concert:

'The

Concert was honoured

with an

exceptionally large

crowd, and the two

new concertos and

other fantasies

which Herr Mozart

played on the

fortepiano were

received with the

loudest applause.

Our Monarch, who,

against his habit,

attended the whole

of the concert, as

well as the entire

audience, accorded

him such unanimous

applause as has

never been heard of

here. The receipts

of the concert are

estimated to amount

to 1,600 gulden in

all’.

The

programme was typical of

Mozart’s 'academies' and

demonstrates the role

that symphonies were

expected to fill as

preludes and postludes

framing an evening's

events:

1. The first 3 movements

of the 'Haffner'

symphony (K. 385)

2. 'Se il padre perdei’

from Idomeneo

(K. 366)

3. A piano concerto in C

major (K. 415)

4. The recitative and

aria ’Misera, dove son!

- Ah! non son’ io che

parlo’ (K. 369)

5. A Sinfonia

concertante (movements 3

and 4 from the serenade

K. 320)

6. A piano concerto in D

major (K. 175 with the

finale K. 382)

7. ’Parto m’affretto’

from Lucio Silla

(K. 135)

8. A short fugue

(’because the Emperor

was present')

9. Variations on a tune

from Paisiello's I

filosofi immaginarii

(K. 398) and as an

encore to that,

10. Variations on a tune

from Gluck's La

Rencontre imprévue

(K. 455)

11. The recitative and

rondo 'Mia speranza

adorata - Ah, non sai,

qual pena' (K. 416)

12. The finale of the

'Haffner' symphony (K.

385)

Which of us wouldn't

give a great deal to be

temporarily transported

in one of

science-fiction’s time

machines to the Burg

Theatre on that Sunday

in March 1783 to hear

such a concert led by

Mozart at the

fortepiano?

The ’Haffner’ symphony

was among the six

symphonies that Mozart

planned to have

published in 1784 and in

the following year the

work was indeed brought

out in Vienna by

Artaria, in the

four-movement version

but without the

additional flutes and

clarinets. The fuller

orchestration appeared

in Paris published by

Sieber with a title page

bearing the legend ‘Du

repertoire du Concert

spirituel'. (The work

had been given at the

Concert spirituel

apparently on 17 April

1783.) Despite the

symphony's wide

availability, Mozart

included it among pieces

that he sold to Prince

von Fürstenberg

'for performance solely

at his court' in 1786.

Having dwelt at some

length on the history of

the 'Haffner’

symphony, we shall be

content to let the music

speak for itself - which

it does so eloquently -

without further

description or analysis.

Symphony in D major,

K.504 (’Prague’)

Mozart's relations with

the citizens of Prague

form

a happy chapter in the

otherwise sad story of

his last years. At a

time when Vienna was

growing indifferent to

Mozart and his music,

Prague couldn’t have

enough of either.

Mozart's Prague

acquaintance Franz Xaver

Niemetschek, who after

Mozart's death was

entrusted with the

education of his son

Carl, has left us the

best account of the

première of

the 'Prague' symphony

and of Mozart's special

relationship wit the

Prague orchestra. His

account, although

written after the fact

and somewhat idealized,

can be shown to be

generally accurate:

I was

witness to the

enthusiasm which [The

Seraglio]

aroused in Prague

equally among those

who were connoisseurs

and those who were

not. It was as if what

had hitherto been

taken for music was

nothing of the kind.

Everyone was

transported - amazed

at the novel hannonies