|

|

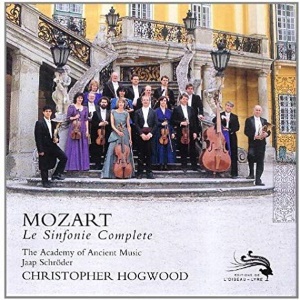

4 LP's

- D171D4 - (p) 1981

|

|

| 3 CD's -

421 104-2 - (c) 1987 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| The Symphonies

- Vol. 5 - Salzburg 1775-1783 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

45' 56" |

|

| Symphony No. 32

in G Minor, K. 318 |

7' 48" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro spiritoso · Andante · Tempo

Primo] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major ("Haffner" Serenade),

K. 250 / 248b |

|

|

|

| -

[Allegro maestoso-Allegro molto ·

Menuetto galante & Trio] |

13' 50" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - [Andante ·

Menuetto & 2 Trios ·

Adagio-Allegro assai] |

24' 18" |

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

45' 33" |

|

| Symphony

No. 33 in B flat Major, K. 319 |

23' 14" |

|

|

| - [Allegro assai ·

Andante moderato · Menuetto &

Trio · Allegro assai] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

("Posthorn" Serenade) in D Major,

K. 320 |

22' 19" |

|

|

| - [Adagio

maestoso-Allegro con spirito ·

Andantino · Presto] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

46' 25" |

|

| Symphony

No. 34 in C Major, K. 338 |

21' 01" |

|

|

| - [Allegro vivace

· Andante di molto più tosto.

Allegretto · Allegro vivace] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 35 "Haffner" in D Major, K.

385 |

25' 24" |

|

|

| - [Marcia K. 408

No. 2 / K. 385a · Allegro con

spirito · Andante · Menuetto &

Trio · Presto] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

4 |

|

45' 41" |

|

| Symphony

No. 36 "Linz" in C Major, K. 425 |

|

|

|

| - [Adagio-Allegro

spiritoso · Andante] |

22' 32" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - [Menuetto &

Trio · Presto] |

14' 56" |

|

|

Symphony

No. 52 in C Major, K. 208 / K.

213c

|

8' 13" |

|

|

| - [Molto allegro ·

Andantino · Presto assai] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap Schröder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

The size of the

orchestra used during these

recordings was 9 first

violins, 8 second violins, 4 violas,

3 cellos, 2 double basses, 2 flutes,

2 oboes, 3 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 4

horns and timpani and was made up

from the following players:

|

|

|

|

| Violins

|

Catherine

Mackintosh (Rowland Ross 1978,

Amati) - Simon Standage

(Rogeri, Brescia 1699) - Monica

Huggett (Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Elizabeth

Wilcock (Grancino, Cremona

1652) - Roy Goodman (Rowland

Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - David

Woodcock (Anon., circa 1775) -

Joan Brickley (Mittewald,

circa 1780) - Alison Bury

(Anon., England circa 1730) - Judith

Falkus (Eberle, Prague, 1733)

- Christopher Hirons (Duke,

circa 1775) - John Holloway

(Sebastian Kloz 1750) - Polly

Waterfield (Rowland Ross 1979

[Amati] & John Johnson 1750) - Micaela

Comberti (Anon., England,

circa 1740) - Miles Golding

(Anon., Austria, circa 1780) - Kay

Usher (Anon., England, circa

1750) - Julie Miller (Anon.,

France, circa 1745) - Susan

Carpenter-Jacobs (Franco

Giraud 1978 [Amati]) - Robin

Stowell (David Hopf, circa

1780) - Richard Walz (David

Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Judith

Garside (Anon., France, circa

1730) - Rachel Isserlis

(John Johnson 1759) - Robert

Hope Simpson (Samuel Collier,

circa 1740) - Catherine Weiss

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) -

Jennifer Helsham (Alan Bevitt

1979 [Stradivarius])

|

|

|

|

|

| Violas

|

Jan Schlapp

(Joseph Hill 1770) - Trevor Jones

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Katherine

Hart (Charles and Samuel Thompson

1750) - Colin Kitching (Rowland Ross

1978 [Stradivarius]) - Nicola Cleminson

(McDonnel, Ireland circa 1760) - Philip

Wilby (Carrass Topham 1974 [Gasparo da

Salo]) - Annette Isserlis (Eberle,

circa 1740 & Ian Clarke 1978

[Guarnieri]) - Simon Rowland-Jones

(Anon., England, circa 1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Violoncellos |

Anthony

Pleeth (David Rubio 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Richard Webb

(David Rubio 1975 [Januarius

Gagliano]) - Mark Caudle

(Anon., England, circa 1700) - Juliette

Lehwalder (Jacob Hanyes 1745) |

|

|

|

|

| Double

Basses

|

Barry

Guy (The Tarisio, Gasparo da

Salo 1560) - Peter McCarthy

(David Tecler, circa 1725 &

Anon., England, circa 1770) |

|

|

|

|

Flutes

|

Stephen

Preston (Anon., France, circe

1790) - Nicholas McGegan

(George Astor, circa 1790) - Lisa

Beznosiuk (Goulding, London,

circa 1805) - Guy Williams

(Monzani, circa 1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Oboes

|

Stanley

King (Jakob Grundmann 1799

& Rudolf Tutz 1978 [Grundmann])

- Clare Shanks (W. Milhouse,

circa 1760) - Sophia McKenna

(W. Milhouse, circa 1760) - David

Reichenberg (Harry Vas Dias

1978 [Grassi]) |

|

|

|

|

Bassoons

|

Jeremy

Ward (Porthaux, Paris, circa

1780) - Felix Warnock

(Savary jeune 1820) - Alastair

Mitchell (W. Milhouse, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Horns

|

William

Prince (Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Keith Maries

(Courtois neveu, circa 1800 &

Anon., Germany (?), circa 1785) - Christian

Rutherford (Courtois neveu,

circa 1800 & Kelhermann, Paris

1810) - Roderick Shaw

(Raoux, circa 1830) - John

Humphries (Halari, circa 1825) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Trumpets |

Michael

Laird (Laird 1977 [German]) -

Iaan Wilson (Laird 1977

[German]) |

|

|

|

|

| Timpani |

David

Corkhill (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1890) - Charles Fulbrook

(Hawkes & Son, circa 1890) |

|

|

|

|

| Harpsichord

|

Christopher

Hogwood, Nicholas McGegan,

David Roblou (Thomas

Culliford, London 1782) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.

Paul's, New Southgate, London

(United Kingdom):

- giugno 1979 (K. 318, 319, 320)

- settembre 1979 (K. 338)

- ottobre 1979 (K. 250)

St. Jude-On-The-Hill, London

(United Kingdom):

- ottobre 1979 (K. 408, 385)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Morten

Winding / John Dunkerley &

Simon Eadon

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - D171D4 (4 LP's) - durata

45' 56" | 45' 33" | 46' 25" | 45'

41" - (p) 1981 - Analogico

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 421 104-2 (3 CD's) - durata

54' 45" | 67' 04" | 63' 17" - (c)

1987 - ADD |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

and the symphonic

traditions of his

time by Neal

Zaslaw

Salzburg

and its Orchestra

The picture of Salzburg

painted by Mozart in his

letters is unflattering in

the extreme, as a series

of excerpts from the years

1775-81 will show:

14 January

1775: 'I fear that

we cannot return to

Salzburg very soon and

Mamma must not wish it,

for she knows how much

good it is doing me to be

able to breathe freely'.

4 September 1776:

'My father has already

served this court for 36

years, and as he knows

that the present

Archbishop cannot and will

not have anything to do

with people who are

getting on in years

[Leopold was 56] , he

doesn't allow it to worry

him, but has taken up

literature, which was

always a favourite study

of his'.

1 August 1777:

'Your Grace [the

Archbishop] will not take

this petition [to leave

Salzburg] amiss, seeing

that when I asked you for

permission to travel to

Vienna 3 years ago, you

graciously declared that I

had nothing to hope for in

Salzburg, and would do

better to seek my fortune

elsewhere'.

23 September 1777:

'...our Mufti [Archbishop]

H[ieronymus] C[olloredo]

is a bastard...'.

26 September 1777:

'They were both amazed and

absolutely refused to

believe that my late

lamented salary used to be

all of 12 gulden, 30

kreutzer [a month]... I am

always in my very best

spirits, for my heart has

been as light as a feather

ever since I got away from

all that chicanery! -

what is more, I have

become fatter'.

30 September 1777 :

'...Salzburg is no place

for me, truly it is not'.

10 December 1777:

'...a town where one is

accustomed to having

stupid enemies, [or] weak

and silly friends who,

because Salzburg's bread

of affliction is

indispensable to them, are

always toadying and are

consequently one thing one

day and another the next'.

19 February 1778:

'...Salzburg, where we are

not in the habit of

contradicting anyone...'.

9 July

1778: '...one of my

chief reasons for

detesting Salzburg [is]

those coarse, slovenly,

dissolute court musicians.

Why,

no honest man of good

breeding could possibly

live with them! Indeed,

instead of wanting to

associate with them, he

would feel ashamed of

them. It is probably for

this very reason that

musicians are neither

popular nor respected

among us. Ah, if only the

orchestra were organised

as they are at Mannheim.

Indeed, I would like you

to see the discipline

which prevails there and

the authority which

Cannabich wields. There

everything is done

seriously. Cannabich, who

is the best director I

have ever seen, is both

beloved and feared by his

subordinates. Morever he

is respected by the whole

town and so are his

soldiers. But certainly

they behave quite

differently from ours.

They have good manners,

are well dressed, and do

not go to pubs and swill.

This can never be the case

in Salzburg, unless the

Prince will trust you or

me and give us full

authority as far as

the music is concerned

- otherwise it's no good.

In Salzburg

everyone - or rather no

one - bothers about the

music. If I were to

undertake it, I should

have to have complete

freedom of action. The

Chief Steward should have

nothing to say to me in

musical matters, or on any

point relating to music.

For a courtier can't do

the work of a

Kapellmeister, but a

Kapellmeister can well be

a courtier'.

7 August 1778: 'Now

for our Salzburg story.

You, most beloved friend,

are well aware how I

detest Salzburg - and not

only on account of the

injustices which my dear

father and I have endured

there, which in themselves

would be enough to make

one want to forget such a

place and blot it out of

the memory for ever! But

let us set that aside, if

only we can arrange things

so as to be able to live

there well. To

live well and to live

happily are two very

different things, and the

latter I could not do

without having recourse to

witchcraft... I have far more

hope of living pleasantly

and happily in any other

place. Perhaps you will

misunderstand me and think

that Salzburg is too small

for me? If so, you are

greatly mistaken. I have

already given some of my

reasons to my father. In

the meantime, content

yourself with this one,

that Salzburg is no place

for my talent. In the

first place, professional

musicians there are not

held in much

consideration, and,

secondly, one hears

nothing, there is no

theatre [this statement is

not strictly accurate],

no opera, and even if they

really wanted one, who is

there to sing? For the

last five or six years the

Salzburg orchestra has

always been rich in what

is useless and

superfluous, but very poor

in what is necessary, and

absolutely destitute of

what is indispensible; and

such is the case at the

present moment'.

11 September 1778:

'To tell you my real

feelings, the only thing

that disgusts me about

Salzburg is the

impossibility of mixing

freely with the people,

and the low estimation in

which the court musicians

are held there -

and - that the Archbishop

has no confidence in the

experience of intelligent

people who have seen the

world... If the Archbishop

would only trust me, I

should soon make his

orchestra famous; of this

there can be no doubt'.

15 October 1778:

'Consider it yourself -

put yourself in my place!

At Salzburg I don't know

how I stand. I am

everything - and yet -

sometimes - nothing!

Nor do I ask so much

nor so little - I

just want something - I

must be somethingl'.

12 November 1778:

'...the Archbishop cannot

pay me enough for that

slavery in Salzburg!

As I said before, I feel

the greatest pleasure at

the thought of paying you

a visit - but only

annoyance and anxiety when

I see myself back at that

beggarly court!'

3 December 1778:

'Ah, how much finer and

better our orchestra might

be, if only the Archbishop

desired it. Probably the

chief reason why it is not

better is because there

are far too many

performances. I have no

objection to the chamber

music, only to the

concerts on a larger

scale'.

8 January

1779: 'I swear to

you on my honour that I

cannot bear Salzburg or

its inhabitants (I mean,

the natives of Salzburg).

Their language - their

manners are quite

intolerable to me'.

16 December 1780:

'...Upon my honour, it is

not Salzburg itself but

the Prince and his noble

disdain which become every

day more intolerable to

me'.

8 April 1781:

'...to waste one's youth

in inactivity in such a

beggarly place is really

very sad - and also

unprofitable'.

16 May 1781:

'...even if I had to beg,

I could never serve such a

master again; for, as long

as I live, I shall never

forget what has happened'.

26

May 1781: '...in

Salzburg - for me at least

- there is not a

farthing's worth of

entertainment. I

refuse to associate with

a good many people there

- and most of the others

do not think me good

enough. Besides, there is

no stimulus for my talent!

When I play or when any of

my compositions are

performed, it is just as

if the audience were all

tables and chairs. If at

least there were a theatre

there worthy of the name'.

The historian's task is

not only to publish

interesting documents, but

also to interpret them. In

this instance we must deal

with three aspects of

Mozart's polemics against

Salzburg; the people, the

Archbishop, and the

orchestra.

It is perhaps true that

the people of Salzburg

were, as the musician

Schubart wrote in the 1770’s,

'exceedingly inclined to

low humour. Their folk

songs are so comical and

burlesque that one cannot

listen to them without

side-splitting laughter.

The Punch-and-Judy

spirit shines through

everywhere...'. The

irony of this, however, is

that Mozart himself,

despite his superior

education and haughty

attitude, was very much of

the same persuasion. His

letters are filled with

Salzburg dialect, local

puns, and coarse jokes.

And his strong complaints

could easily obscure the

fact that the Mozarts also

had dear friends and

strong supporters in their

native city. The clue here

lies in Leopold's

snobbery, for he had

raised his son to be

socially ambitious and to

avoid unnecessary contact

with the lower classes.

Hence his displeasure at

Wolfgang's choice of wife

and his delight at

arranging for Nannerl to

marry into a higher social

class. The son was trying

to please the father when

he wrote that he refused

'to associate with a good

many people', but he was

expressing his own

anguished' predicament -

the predicament of a lad

raised as a bourgeois in

the midst of Salzburg's

vestigial feudalism where

the middle class was small

and powerless - when he

added, 'and most of the

others do not think me

good enough'. The Mozarts'

profound disillusionment

arose not only from the

Archbishop's bad treatment

and poor pay, but from the

contrast with their

treatment elsewhere.

During their extensive

travels the Mozarts,

because they dressed well,

spoke well, and came

well-introduced, were

accepted as near equals by

the upper classes of

dozens of European courts

and cities. But a prophet

may be without honour in

his own land, and at home

Leopold and Wolfgang were

merely liveried servants.

The Archbishop may well

deserve the hatred of

generations of Mozart

worshippers but, as is so

often the case, there is

another side to the story.

It is true, for instance,

that the able Leopold was

passed over time and again

for the position of Kapellmeister,

and died still only Vizekapellmeister.

But he had been away on

tour a good deal of the

time, and his best

energies had gone into

raising his son and not

into serving the

Archbishop and working

toward advancement at

home. In Wolfgang's case,

it is instructive that,

although many of the

Viennese nobility admired

him greatly, none offered

him a permanent post after

he settled there, for he

could be difficult,

haughty, defensive,

mercurial, and painfully

conscious of his unusual

gifts-in short, not the

personality to make a good

courtier or the head of a

large musical

establishment. The

contrast with Joseph

Haydn is striking, for

although Haydn inevitably

fought unjust treatment at

the hands of his Lords,

the Princes Esterházy,

he never forgot his

station in life and he

aspired to serve well and

loyally. Most of Mozart's

potential employers

evidently preferred as

their Kapellmeisters any

one of a hundred competent

but uninspired musicians

to the brilliant but

uppish Mozart.

As for the Salzburg

orchestra, it was indeed

going through a difficult

period in which there was

even for a time, in the

late 1770's, no Kapellmeister

at all. Discipline was

undoubtedly less than

ideal. But it was a

good-sized, active

organization that gave

several performances a

week (too many, Mozart

tells us), and while it

may not have been up to

the standards Mozart had

encountered in Mannheim

and a few other European

musical centres, it was

far better than many of

the other orchestras he

heard on his travels. (It

should be noted that the

Mozarts were seldom

generous with their praise

of music or musicians).

The official roster of the

Salzburg court orchestra

in the early1780's

s included Luigi Gatti, Kapellmeister,

Leopold Mozart, Vizekapellmeister

(and violinist), Johann

Michael Haydn, Konzertmeister

(and violist and

organist), 2 other

organists, 11 other

violinists, 1 other

violist, 2 cellists, 4

double bass players, 2

bassoonists, 3 oboists, 2

horn players, and 3

trombonists. Many of these

musicians played more than

one instrument, and they

were supplemented on

important occasions by

additional performers

drawn from the town waits,

the trumpet and kettledrum

players of the local

militia, and various

amateur performers at

court. Thus the

composition of the

Salzburg orchestra varied

widely from season to

season and from occasion

to occasion. As

reconstituted for these

recordings, the orchestra

is as it may have been

heard at festive events

during the year: the

strings 9-8-4-3-2, and the

necessary woodwind, brass,

kettle drums and

harpsichord, with 3

bassoons doubling the bass

line whenever obbligato

parts for them are not

indicated.

The

Symphony as a Genre

After Beethoven, the

symphony was the most

important large-scale

instrumental genre for

the Romantic composers.

Their conception of the

symphony as an extended

work of the utmost

seriousness, intended as

the centrepiece of a

concert, is very far

from what the musicians

of the second half of

the 18th century had in

mind for their

symphonies. This can be

seen by comparing the

large number of

symphonies turned out

then with the handful

written by the major

19th-century

symphonists. It

can also be seen in the

small number and brevity

of passages devoted to

symphonies in the

newspaper accounts,

memoires and

correspondence of the

period. And it can be

seen in the uses to

which 18th-century

symphonies were put.

A pair of

contemporaneous German

definitions and

descriptions of the

symphony may serve to

illustrate how these

works were viewed.

Christian Friedrich

Daniel Schubart, who

became acquainted with

the Mozarts when he

visited Salzburg in the

1770's,defined the

symphony as follows:

'This genre of music

originated from the

overtures of musical

dramas, and came finally

to be performed in

private concerts. As a

rule it consists of an

allegro, an andante, and

a presto. However, our

artists are no longer

bound to this form, and

often depart from it

with great effect.

Symphony in the present

fashion is, as it were,

loud preparation for and

vigorous introduction to

hearing a concert'.

Johann

Philipp Kirnberger,

writing a definition for

Sulzer's Allgemeine

Theorie der schönen

Künste,

entered into more

detail: 'In the

symphony... where there

is more than one

instrument to a part,

the melody must have

reached its highest

expression in the notes

as written out, and in

no part can the

slightest ornamentation

or coloratura be

tolerated. Becauseit

will not be practised

like the sonata, but

must be sight-read, it

should contain no

difficulties that cannot

be met and performed

clearly by several

players simultaneously.

'The

symphony is particularly

suited to the expression

of greatness, solemnity

and stateliness. Its

purpose is to prepare

the listener for the

important music that

follows, or, in a

concert in a hall, to

exhibit all the pomp of

instrumental music. lf

it is to carry out this

purpose adequately and

become part of the opera

or church music that it

precedes, then, besides

an expression of

greatness and solemnity,

it must also have a

character that puts the

listener in the proper

frame of mind for the

piece to follow, and in

the manner in which it

is composed, must show

whether it befits the

church or the theatre.

'The concert symphony,

which constitutes an

independent entity with

no notion of its serving

to introduce other

music, achieves its

purpose solely through

asonorous, brilliant,

and fiery manner of

writing. The allegros of

the best concert

symphonies contain great

and bold ideas; free

treatment of

counterpoint; apparent

disorder in melody and

harmony; strongly marked

rhythms in various

manners; powerful bass

lines and unison

passages; inner voices

of melodic significance;

free imitations; often a

theme treated fugally;

sudden shifts and

modulations from one key

to another, which are

often all the more

striking the more

distant the relationship

between the keys is;

strong shadings of forte

and piano, and

especially the

crescendo, which, when

it accompanies both an

ascending melodic line

and an intensifying

expression, is of the

greatest effect...'.

Mozart wrote his

symphonies as

curtainraisers to plays,

operas, cantatas,

oratorios, and private and

public concerts. They may

occasionally have been

used as part of church

services. In

addition to opening

concerts with symphonies,

Mozart sometimes also used

them to end concerts, or

even to begin and end each

half of a long concert. Judging

by the number of

symphonies he wrote in

Salzburg (or that he wrote

elsewhere and then used in

Salzburg), there must have

been a steady demand for

them there.

With the arguable

exception of the last few,

Mozart's symphonies were

perhaps intended to be

witty, charming,

brilliant, and even

touching, but undoubtedly

not profound, learned, or

of great significance. The

main attractions at

concerts were not the

symphonies, but the vocal

and instrumental solos and

chamber music that the

symphonies introduced.

Approaching Mozart's

symphonies with this

attitude in mind relieves

them of a romantic

heaviness under which they

have all too often been

crushed.

Performance Practice

The use of 18th-century

instruments with the

proper techniques of

playing them gives to the

Academy of Ancient Music a

clear, vibrant, articulate

sound. Inner voices are

clearly audible without

obscuring the principal melodies.

Rhythmic patterns and

subtle differences in

articulation are more

distinct than can usually

be heard with modern

instruments. The use of

little or no vibrato

serves further to clarify

the texture. At lively

tempos and with this

luminous timbre, the

observance of all of

Mozart's repeats no longer

makes movements seem too

long. A special instance

concerns the da capos of

the minuets, where, an

ancient oral tradition

tells us, the repeats are

always omitted. But, as we

were unable to trace that

tradition as far back as

Mozart's time, we

experimented by including

those repeats as well.

Missing instruments

understood in 18th-century

practice to be required

have been supplied: these

include bassoons playing

the bass-line along with

the cellos and double

basses, kettle drums

whenever trumpets are

present (except in the

case of the Symphony

in Eb, K.184,

where chromaticism renders

their use less idiomatic)

and the harpsichord

continuo. No conductor is

needed, as the direction

of the orchestra is

divided in true

18th-century fashion

between the concertmaster

and the continuo player,

who are placed so that

they can see each other

and are visible to the

rest of the orchestra.

Following 18th-century

injunctions to separate

widely the softest and

loudest instruments, the

flutes and trumpets are

placed at opposite sides

of the orchestra. And the

first and second violins

are placed at the left and

right respectively,

making meaningful the

numerous passages Mozart

wants tossed back and

forth between them.

Musical Sources and

Editions

Until recently

performers of Mozart's

symphonies have relied

upon the editions drawn

from the old complete

works, published in the

19th century by the

Leipzig firm of

Breitkopf & Härtel.

During the past quarter

century, however, a new

complete edition of

Mozart's works (NMA)

has been slowly

appearing, published by

Bärenreiter

of Kassel under the

aegis of the Mozarteum

of Salzburg. The NMA

has been used for almost

all the symphonies from

K.128 to K.551. For the

early symphonies not yet

published in the NMA,

editions have been

created especially for

these recordings,

drawing on Mozart's

manuscripts when they

could be seen, and on

18th- and 19th-century

copies in those cases

where the autographs

were unavailable. (14 of

Mozart's symphonies are

among musical

manuscripts formerly in

the Berlin library but

now being held in Poland

and inaccessible to

Western musicologists.)

Copyright

© 1980

by Neal Zaslaw

A Note

Concerning the

Numbering of Mozart's

Symphonies

The first

edition of Ludwig Ritter

von Köchel's

Chronological-Thematic

Catalogue of the

Complete Works of

Wolfgang Amaadé

Mozart was published

in 1862 (=K1).

It

listed all of the

completed works of Mozart

known to Köchel

in what he believed to be

their chronological order,

from number 1 (infant

harpsichord work) to 626

(the Requiem). The second

edition by Paul Graf von

Waldersee in 1905 involved

primarily minor

corrections and

clarifications. A

thoroughgoing revision

came first with Alfred

Einstein's third edition,

published

in 1936 (=K3).

(A reprint of this edition

with a sizeable supplement

of further corrections and

additions was published in

1946 and is sometimes

referred to as K3a.)

Einstein changed the

position of many works in

Köchel's

chronology, threw out as

spurious some works Köchel

had taken to be authentic,

and inserted as authentic

some works Köchel

believed spurious or did

not know about. He also

inserted into the

chronological scheme

incomplete works,

sketches, and works known

to have existed but now

lost. These Köchel

had

placed in an appendix (=Anhang,

abbreviated Anh.)

without chronological

order. Köchel's

original numbers could not

be changed, for they

formed the basis of

cataloguing for thousands

of publishers, libraries,

and reference works.

Therefore, the new numbers

were inserted in

chronological order

between the old ones by

adding lower-case letters.

The so-called fourth and

fifth editions were

nothing more than

unchanged reprints of the

1936 edition, without the

1946 supplement. The sixth

edition, which appeared in

1964 and was edited by

Franz Giegling, Alexander

Weinmann, and Gerd Sievers

(=K6),

continued Einstein's

innovations by adding

numbers with lower-case

letters appended, and a

few with upper-case

letters in instances in

which a work had to be

inserted into the

chronology between two of

Einstein's lowercase

insertions. (A so-called

seventh edition is an

unchanged reprint of the

sixth). Hence, many of

Mozart's works bear two K

numbers, and a few have

three.

Although it was not Köchel's

intention in devising his

catalogue, Mozart's age at

the time of composition of

a work may be calculated

with some degree of

accuracy from the K

number. (This works,

however, only for numbers

over 100). This is done by

dividing the number by 25

and adding 10. Then, if

one keeps in mind that

Mozart was born in 1756,

the year of composition is

also readily approximated.

The old Complete Works of

Mozart published 41

symphonies in 3 volumes

between 1879 and 1882,

numbered 1 to 41 according

to the chronology of K1.

Additional symphonies

appeared in supplementary

volumes and are sometimes

numbered 42 to 50,

even though they are early

works.

Bibiography

- Anderson,

Emily: The Letters

of Mozart & His

Family (London,

1966)

- Burney,

Charles: The

Present State of

Music in Germany,

The Netherlands, and

United Provinces

(London, 1773)

- Della

Croce, Luigi: Le

75 sinfonie de

Mozart (Turin,

1977)

- Eibl,

Joseph Heinze, et al.:

Mozart: Briefe und

Aufzeichnungen

(Kassel, 1962-75)

- Koch,

Heinrich: Musilcalisches

Lexikon

(Frankfort, 1802)

- Landon,

H. C. Robbins: 'La

crise romantique dans

la musique

autrichienne vers

1770: quelques

précurseurs inconnus

de la Symphonie en sol

mineur (KV 183) de

Mozart', Les

influences étrangères

dans l'oeuvre de W.

A. Mozart

(Paris, 1958)

- Larsen,

Jens

Peter: 'A Challenge to

Musicology: the

Viennese Classical

School', Current

Musicology

(1969), ix

- Mahling,

Christoph-Hellmut:

'Mozart und die

Orchesterpraxis seiner

Zeit', Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1967)

- Mila,

Massimo: Le

Sinfonie de Mozart

(Turin, 1967)

- Saint-Foix,

Georges de: Les

Symphonies de Mozart

(Paris, 1932)

- Schneider,

Otto, and Anton

Algatzy: Mozart-Handbuch

(Vienna, 1962)

- Schubart,

Ludwig: Christ, Fried.

Dan. Schubart's

Ideen zu einer

Asthetik der

Tonkunst

(Vienna, 1806)

- Schultz,

Detlef: Mozarts Jugendsinfonien

(Leipzig, 1900)

- Sulzer,

Johann

Georg: Allgemeine

Theorie der schönen

Künste

(Berlin, 1771-74)

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'The Compleat

Orchestral Musician',

Early Music

(1979), vii/1

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'Toward the

Revival of the

Classical Orchestra',

Proceedings of the

Royal Musical

Association

(1976-77), ciii

Copyright

© 1979 by Neal

Zaslaw

|

|

The

Symphonies of 1775-83

During the

years 1770-75 Mozart had

an attack of what

Massimo Mila has

charmingly called

'symphony fever', for

during that 6-year span

he created no fewer than

36 symphonies. In the

following 8 years the

fever had subsided,

however, and we record

only 9 symphonies. This

reduced production is

undoubtedly in part due

to Mozart's

disillusionment with

Salzburg which is so

painfully documented in

his letters. He was no

longer so interested in

impressing his compatriots,

and must often have

fallen back on his large

stock of older works

when a symphony was

called for. Even after

Mozart's move to Vienna,

however, where there

were numbers of

potential employers

among the nobility whom

Mozart hoped to impress,

the production of

symphonies remained

small. He was by then

much more interested in

piano concertos in which

he could display his

considerable skill as a

soloist, and above all

in opera, the domain in

which he hoped to make

his principal

reputation.

The symphony based on

the overture to Il

re pastore

and those drawn from the

Posthorn serenade and

from the 2 works for the

Haffner family were the

last works in which

Mozart engaged in such

refurbishment. On the

one hand, after settling

in Vienna he abandoned

the Salzburgian genre of

the orchestral serenade.

On the other hand, the

overtures to his great

operas had apparently

evolved to the point at

which he no longer

considered them

interchangeable with

concert symphonies.

Symphony in C major,

K. 213c (102)

This symphony is derived

from Mozart's opera Il

re pastore ('The

shepherd king'), a

famous libretto by

Metastasio set by a

number of composers of

the period, including

Gluck. Mozart composed

the opera in the space

of about 6 weeks prior

to its premiere in

Salzburg on 23 April

1775. The opera had been

commissioned to

celebrate a visit to

Salzburg by the Archduke

Maximilian, youngest son

of the Austrian Empress

Maria Theresa. As

Salzburg had no opera

house, this work may

well have been given in

concert form, and indeed

the Archduke's travel

diary speaks only of

attending a 'cantata'.

The plot concerns the

conflict between love

and duty in a foundling

prince who, having been

raised as a shepherd, is

reluctant to give up his

rustic life for the

burdens of the throne.

Mozart's one-movement

'overtura' to the opera

begins with the same

three chords with which

his previous symphony

(K. 213a) began, but

there follows in this

case a movement much

more concise and Italianate.

This leads without a

break to an andantino

that Mozart manufactured

from the first aria of

the opera. This he

accomplished by

substituting a solo oboe

for the shepherd king

Aminta (sung by a

castrato) and by writing

a new ending 8 bars

long, which leads, again

without pause, into a

totally new finale. This

movement, presto assai

in 2/4, is an extended

rondo in the style of a

country dance.

The aria upon which the

middle movement of the

symphony is based finds

Aminta with flute in

hand wondering what fate

holds for him and his

shepherdess. The text

reads:

Intendo, amico

rio,

quel basso mormorio,

tu chiedi in tua

favella;

il nostro ben dov'e?

(I understand, o

friendly brook,

your low murmuring,

you are asking in your

way

where our beloved is.)

Mozart took this

symphony with him on his

trip to Paris in 1778,

using it on the way to

close a concert at the

house of the Mannheim

composer, Christian

Cannabich,on 13 February

1778. The rest of the

concert consisted of a

symphony by Cannabich;

Mozart's piano concerto

in Bb, K. 238, played by

Cannabich's daughter

Rosa; Mozart's oboe

concerto in C, K. 314; 2

arias from Lucio

Silla, K. 135,

sung by Mozart's current

love and future sister-in-law

Aloysia Weber; Mozart's

piano concerto in D, K.

175, performed by

himself; and a half hour

of his extemporisation

at the fortepiano.

Symphony in D major,

K. 248b (250)

Mozart's 'Haffner'

serenade is a much-loved

work (not to be

confused, however, with

the ‘Haffner' symphony,

K. 385, discussed

later). The Haffners and

the Mozarts were friends

of long standing in

Salzburg, and when Maria

Elisabeth (‘Liserl')

Haffner was to marry, it

was to be expected that

the 20-year-old Mozart

should be asked for some

suitable music to

celebrate the occasion.

The serenade which

resulted received its

first performance at an

eve-of-the-wedding

party, and the Salzburg

court councillor von Schiedenhofen

who was present entered

in his diary:

'21 luly 1776: After

dinner I went to the

bridal

music that young Herr

Haffner ordered to be

put on for his sister

Liserl. It

was by Mozart,

and done at their summer

house in Loreto

Street.'

Like most of Mozart's

orchestral serenades,

this work consists of a

march followed by a

mixture of symphony and

concerto movements (in

this instance, a

three-movement violin

concerto). At some later

date Mozart or his

father ordered a copyist

to extract a set of

orchestra parts

containing only the

symphonic movements. To

this Leopold added a

part for the kettle

drums (lacking in the

serenade score), and

Wolfgang looked through

the set of parts and

entered a number of

corrections and

clarifications. At yet a

later date, these

corrected parts were

used by another copyist

who added a second set

of string parts. The

resulting set of 16

orchestral parts was in

Mozart's possession at

his death, which

suggests that he used

them for his concerts in

Vienna. Furthermore, it

is likely that this

symphony was one of 6

that in 1784 Mozart

hoped to have published,

the set to be dedicated

to Prince von Fürstenberg.

(In the event, however,

only 2 appeared - K. 319

and 385 - and without

the proposed

dedication.)

The symphony version may

perhaps have been

created as early as

1776-77, for we know

that in preparation for

his departure for

Mannheim and Paris,

Wolfgang, in September

1777 assembled a large

collection of orchestral

parts of his recent

symphonies. In any case,

the symphony was in

existence by September

1779, for an entry in

Nannerl's diary in

Wolfgang's hand on the

24th of that month

mentions a performance

in Salzburg of 'the

Haffner music'. This

could, of course, be

taken to refer to the

serenade version, except

that on 18 March 1780

Mozart again entered the

details of a concert

programme into his

sister's diary, and the

first of the nine items

listed is clearly

designated 'A symphony

(namely the Haffner

music)'. As a serenade

was designed to fill an

entire occasion while a

symphony was to

introduce other works,

this was most probably

the symphony version.

The opening, allegro

maestoso in common time,

is little more than an

extended fanfare moving

from tonic to dominant,

spread over 35 bars and

filled with lovely

orchestral figurations.

After a brief pause, the

allegro molto alla breve

opens unisono, a

texture which recurs

several times during the

movement with good

dramatic effect. The

movement is on a large

scale for a symphony

movement of the late

1770's, with

an unusually extended

and chromatic

development section

based on material from

the allegro maestoso

introduction.

Differences between this

version and the serenade

include (aside from the

written-out kettle

drums) the omission of

the repeat of the

exposition and the

addition of a fanfare

for oboes, horns and

trumpets at the end

where there had been a

grand pause.

'Menuetto galante’ is an

unusual designation, and

perhaps best rendered

'fashionable minuet'.

Fashionable or not, it

is a particularly long

and beautiful minuet.

The trio is not without

its touches of pathos.

Mozart rewrote this trio

for the symphony

version, changing a

broken-chord triplet

accompaniment in the

second violins (as in

Beethoven's 'Moonlight'

sonata) to repeated

notes, and adding oboes

and bassoons to what was

originally for strings

only.

The andante which

follows was taken over

unchanged from the

serenade. It reveals its

origins by its sprawling

dimensions. The movement

is of a particularly

original formal design,

perhaps best described

as an elaborate rondo

influenced by the double

theme-and-variations

format favoured by Joseph

Haydn for his symphony

andantes. It is

difficult to listen to

this movement without

imagining (Italian)

words, for the melodies

and rhythms are

reminiscent of many

arias of the period. It

is perhaps this aspect

of the movement that

prompted Della Croce to

hypothesize a nuptial

programme. He hears 'the

characterization of the

two spouses, who

correspond respectively

to the principal theme,

pensive and angelic, and

a second, more

ingratiating theme,

nearly always entrusted

to the oboes'. This

analysis, however,

leaves us to guess what

(or whom) several other

themes may represent.

Two or three minuets and

minuets with two or

three trios were common

in Salzburg orchestral

serenades but uncommon

(although not unheard

of) in symphonies.

Certain late 18th and

early 19th century

manuscripts of this

symphony have the

'superfluous' movements

excised, suggesting the

growth of a concept of

symphonic format more

rigid than that which

Mozart himself held in

the 1770s. A pair of

flutes replace the oboes

in the second minuet and

its 2 trios. In

an attractive touch of

rustic drone near the

end of the minuet's

second section, Mozart

hints at the sound of

the hurdy-gurdy, while

the first trio features

a flute and bassoon duet

and the second gives the

entire wind band a

chance to shine.

The finale opens with a

16-bar adagio of great

beauty, leading into a

large-scale jig movement

in sonata form with both

halves repeated and a

coda. The music is

similar in character to

the finale of Joseph

Haydn's Symphony No. 8 -

a movement entitled 'La

Tempesta'. If

these storms are a bit

too big to fit into a

teacup, they are

nonetheless among the

most genial storms one

will ever have to

weather.

Saint-Foix comments upon

'the abnormal length of

the movements, their

variety, their

brilliance' and Della

Croce calls the work

'one of the richest,

most solid and most

elaborate symphonies'

that Mozart had thus far

composed. It

must have been popular,

judging by the dozens of

manuscript copies dating

from the 18th and early

19th centuries as well

as André's edition of

1792. During this period

the serenade from which

the symphony was drawn

remained virtually

unknown.

Symphony in G major,

K. 318

Dated 26 April 1779,

this was the first

symphony that Mozart

composed after his

abortive trip to Paris.

Because the format of

this work is unlike

Mozart's other

symphonies but similar

to some Parisian opera

comique overtures by

Grétry, Mozart's

biographers have exerted

themselves trying to

guess for which stage

work this 'overture' may

have been intended.

Hermann Deiters

suggested that it was

for Thamos,

King of Egypt (K.

345/336a) while Einstein

thought that it was for

the untitled and never

completed Singspiel

now known as Zaide

(K. 344/336b). But the

work's date of

composition is too late

for the first version of

Thamos and too

early for Zaide

or for the second

version of Thamos.

If

in fact the work was

destined for something

other than the usual

church, court or chamber

concerts in Salzburg,

then it was, perhaps

written for the

theatrical troupe of Johann

Heinrich Böhm.

This troupe of nearly 50

actors, dancers and

singers performed

various of Mozart's

works, including Thamos

and a Gennan version of

La finta giardiniera

(K. 196) entitled Die

verstellte Gärterin.

Böhm's

troupe was to be

resident in Salzburg

during the winter of

1779-80, but in April

1779 it was still in

Augsburg, and Mozart

(through the good

offices of his Augsburg

cousin Maria Anna Thekla

Mozart, known as 'Das Bäsle')

was in correspondence

with Böhm

about providing

additional music for his

productions.

All editions of the Köchel

catalogue as well as the

new Mozart edition have

subtitled this work

'ouverture'. There is no

authority for this

label, which is

apparently intended to

make a distinction

between concert

symphonies and

theatrical overtures

- a distinction that

hardly existed at the

time. Mozart himself

headed his score simply

'Sinfonia'. That he

approved of its use in

the theatre (as he

probably would have done

with any of his

symphonies) is not in

question, as he provided

it (along with 2 new

vocal numbers, K. 479

and 480) as the overture

for a Viennese

production of Bianchi's

opera buffa La

Villanella rapita

in 1785. And it was as

the overture to La

Villanella rapita

that this work was

published and known to

the 19th century.

The symphony calls for

pairs of flutes, oboes

and bassoons, with 4

horns and strings. The

trumpets and

kettle-drums do not

appear in the original

score, but were copied

in separate parts by

Mozart at some later

date, perhaps for La

Villanella rapita

in 1785.

The opening allegro

spiritoso is a

beautifully crafted

sonata-form movement

with especially fine

handling of orchestral

sonorities. In several

passages, for instance,

the basso of

Baroque tradition is

resolved into

independent parts for

bassoon, cello and

double bass, creating

novel timbral effects.

At the point in the

movement where the

recapitulation might be

expected, the allegro

breaks off and an

andante of considerable

poignancy and scope is

heard. This leads

without pause to a

'primo tempo' which,

after a few bars of

transition, places us

not at the beginning of

the recapitulation but

rather 6 bars before the

return of the so-called

'second subject'. Then

follows the rest of the

recapitulation with the

'missing' opening of the

recapitulation reserved

as a brilliant coda.

Symphony in Bb major,

K. 319

The autograph is marked

'Salzburg, 9. Juli

1779'. Unfortunately the

pages from Nannerl's

diary covering the

period between 16 June

and 14 September of that

year are missing, and no

other document gives us

a clue to the reason for

Mozart writing this

symphony. The work

originally contained

only 3 movements; the

minuet was added later

in Vienna, perhaps for

one of the concerts

Mozart gave there in

1782. This symphony is

one of the 6 that Mozart

ear-marked for

publication in 1784, and

it did in fact appear

the following year. In

1786 it was among 12

works that Mozart

offered to Prince von Fürstenberg

for his exclusive use.

Mozart's double

deception - representing

a seven-year-old work as

recent and offering it

for exclusive use when

it had already been

published - was soon

uncovered, but the

Prince, in an apparent

display of noblesse

oblige, paid Mozart the

amount originally agreed

upon.

The allegro assai in 3/4

is a sonata-form

movement without

repeats, filled with

lively ideas of a much

more conventional stripe

than those of the

previous symphony. To

Saint-Foix

the movement has a

pastoral character and a

Viennese lilt, and the

latter point is

supported by Abert, who

compares the movement to

Schubert. In

the development section

the attentive listener

will note the appearance

of the famous 4-note

motto (do-re-fa-mi) with

which the finale of the

'Jupiter'

symphony opens. This

motto, used by dozens of

composers before and

after Mozart, originated

in sacred vocal

polyphony, but does not

appear to have been

associated with any

particular words. Mozart

himself, for instance,

used it in one Mass (K.

192) for the words

'Credo, credo' and in

another (K. 257) for the

words 'Sanctus,

sanctus'.

The andante moderato is

in the form

A-B-A1B1-A-Coda, with

the A1 section

especially nicely

handled imitatively,

first in the strings in

the dominant and then in

the winds in the tonic.

This cantabile movement

is dominated by the

strings in rather a

chamber-music vein, with

the dynamic nuances

marked with particular

care by Mozart.

Saint-Foix and Larsen

both remark upon the

supposed Viennese

character of the minuet

(would they have done so

had they not known the

movement to have been

composed in Vienna

instead of Salzburg?),

by which they

undoubtedly refer to the

conciseness of the whole

and especially to the Ländler-like

trio.

The finale begins as if

it were simply one more

brisk jig-finale, but

Mozart has a few tricks

up his sleeve. The jig's

triplets alternate with

a march's duplets (and

occasionally the two

overlap), the wind

writing is exceptionally

felicitous, and the

development section is a

fine example of pseudo-counterpoint,

which, while never

exceeding two real

voices at any moment,

creates the illusion of

many-layered polyphony.

Symphony in D major,

K. 320

Dated Salzburg, 3 August

1779', the serenade from

which this symphony was

drawn was written,

according to Mozart's

Prague acquaintance

Niemetschek, for

Archbishop Colloredo's

name-day (30 September).

However, Mozart seldom

wrote down a piece so

far in advance of a

deadline, and he himself

referred to this work in

a letter by the term

'Finalmusik'. The

so-called

'Final-Musiken', usually

given on a Wednesday

since there was a school

holiday on Thursdays,

were serenades which the

students of Salzburg

University's

philosophical faculty

offered at the end of

the academic year (which

fell in early August) to

the Prince-Archbishop at

his summer residence

’Mirabell’ and to their

professors in front of

the University. Mozart

created the symphony by

omitting the serenade's

march, its two movements

for concertante winds,

and both of its minuets

with their trios.

A set of parts for the

symphony version of this

work preserved at Graz

has corrections in

Mozart's hand. It

appears to be of

Viennese origin,

suggesting performances

of the symphony there in

the 1780's. The symphony

was a popular one,

judging from the many

manuscripts of it found

in European libraries

and archives, and was

perhaps one of the 6

that Mozart hoped to

publish in 1784. In

fact, however, it was

published only in 1792.

The first movement

begins majestically with

a 6-bar adagio maestoso

introduction, leading

directly into a

brilliant allegro con

spirito in sonata form

without repeats. An

interesting and

effective feature of the

movement is found at the

recapitulation , where

the adagio material

reappears in a slightly

recomposed version and

without a tempo change.

This Mozart accomplishes

by doubling the note

values, so that a minim

in allegro is precisely

equal to a crotchet in

adagio.

The andantino in D minor

is exceptionally

profound for a serenade

or a symphony of this

period, in which we

usually find less

chromaticism, a more

songful attitude, and a

major key (most often

the subdominant). The

movement is a fully

fledged sonata-form

movement with both

sections repeated.

The finale, presto alla

breve, is, like the

other movements, in

sonata form, here

without repeats. lt

begins unisono

and hurtles through its

nearly 300 bars in a

decidedly light-hearted

manner. Mozart saves

some especially

attractive bits for the

oboes in the development

section which, despite

its thematic

manipulation and

imitative style,

maintains the buffo

character of the rest of

the movement.

Symphony in C major,

K. 338

This is Mozart's last

symphony written in

Salzburg, although not

the last written for

Salzburg (for which, see

K. 385 below). He

labelled the autograph

'Sinfonia di Wolfgango

Amadeo Mozart m[anu] pr[opria]

le 29 d'Agosto,

Salsbourg [sic]1780'.

We learn from Nannerl's

diary that her brother

played at court on the

2nd, 3rd and 4th of

September; one of these

occasions may therefore

have seen the premiere

of this symphony.

Furthermore, Wolfgang

already knew that he was

to leave for Munich on 5

November to oversee the

preparation of Idomeneo,

and he may have wanted a

new symphony in his

baggage in case an

opportunity to present

himself in a concert

there were to

materialize. This

symphony remained in

Mozart's affections, for

it was probably

performed in Vienna on 3

April 1781 by the Tonkünstler-Societät

and on 26 May 1782 at

the Augarten, it was

among 6 symphonies

earmarked for

publication in 1784 (but

did not actually see

print until 1797), and

was among 12 works

offered to Prince von Fürstenberg

for his exclusive use in

1786. Indeed, a set of

parts for this work with

corrections in Mozart's

hand are still in the Fürstenberg

collection at

Donaueschingen.

The first movement

(Mozart originally

headed it 'allegro' but

later added to that

'vivace') is in sonata

form without repeats. It

opens with conventional

fanfare materials, but

Mozart, by inserting

echoes and extensions of

that material, gives it

a special shape and

considerable

individuality. One soon

senses in this movement

Mozart's interest in

longer musical

sentences, and

paragraphs in which a

more sustained musical

logic begins to replace

the shorter-breathed,

patchwork-quilt designs

of his earlier

symphonies.

As a second movement

there was originally a

minuet, but for unknown

reasons Mozart tore it

from the manuscript, and

it is lost except for

the first 14 bars which

were written on the back

of the final page of the

opening movement. The

notion promulgated by

Einstein that the

symphonic minuet, K.

409, in C major was

written to be added to

this symphony is

incorrect. K. 409 is far

too long to fit this

symphony, and it calls

for different forces.

The slow movement is

labelled in the

autograph score 'andante

di molto', but Mozart

must have found that

this was interpreted

slower than he wished

it, for in the

concertmaster's part in

Donaueschingen he added

'più

tosto allegretto'. This

movement for strings

(with divided violas)

and bassoon doubling the

bassline, is in binary

form, or as some prefer

to call it, sonata form

without development

section. Larsen hears

nothing here but opera,

including anticipations

of Susanna and Zerlina.

Saint-Foix finds 'a

delicacy and emotion...

unparalleled even in the

work of Mozart', but to

Della Croce the movement

is archaic, filled with

melodic clichés, and not

worthy of the movements

flanking it. Thus our

uncertain progress

across the quicksands of

musical criticism.

The finale, allegro

vivace, is another huge

jig in sonata form,

with both sections

repeated. Mozart gives a

special concertante role

to the oboes. The

increased breadth of

conception of the first

movement is audible

again here.

Symphony in D major,

K. 385 (’Haffner’)

The circumstances

surrounding the creation

of this work are more

fully documented than

those for any other of

Mozart's symphonies. In

mid-July

1782 Mozart's father

wrote to him in Vienna

requesting a new

symphony for

celebrations surrounding

the ennoblement of

Mozart's childhood

friend Siegmund Haffner

the younger.

On 20 luly Mozart

replied:

'Well,

I am up to my eyes

in work. By Sunday

week I have to

arrange my opera [The Abduction

from the Harem, K.

384] for wind

instruments,

otherwise someone

will beat me to it

and secure the

profits instead of

me. And now you ask

me to write a new

symphony too! How

on earth can I do

so? You have no idea

how difficult it is

to arrange a work of

this kind for wind

instruments, so that

it suits them and

yet loses none of

its effect. Well, I

must just spend the

night over it, for

that is the only

way; and to you,

dearest father, I

sacrifice it. You

may rely on having

something from me by

every post. I shall

work as fast as

possible and, as far

as haste permits, I

shall write

something good'.

Although

Mozart was prone to

procrastination and to

making excuses to his

father, in this instance

his complaints may well

have been justified, for

having just completed

the arduous task of

launching his new opera

(the première

was on 16 July),

Mozart moved house on 23

July

in preparation for his

marriage. By 27

July

he reported to his

father:

‘You

will be surprised

and disappointed to

find that this

contains only the

first Allegro; but

it has been quite

impossible to do

more for you, for I

have had to compose

in a great hurry a

serenade [probably

K.375],

but for wind

instruments only

(otherwise I could

have used it for you

too). On Wednesday

the 31st I shall

send the two

minuets, the Andante

and the last

movement. If I can

manage to do so, I

shall send a march

too. If not, you

will just have to

use the one from the

Haffner

music [K.249],

which is quite

unknown. I have

composed my symphony

in D major, because

you prefer that

key.'

On 29 July

Siegmund Haffner

the younger was ennobled

and added to his name

'von Imbachhausen'. On

the 31st, however,

Mozart could still only

write:

'You

see that my

intentions are good

- only what one

cannot do, one

cannot! I won't

scribble off

inferior stuff. So I

cannot send you the

whole symphony until

next post-day. I

could have let you

have the last

movement, but I

prefer to despatch

it all together, for

then it will cost

only one fee. What I

have sent you has

already cost me

three gulden.'

On 4

August Mozart and

Constanze Weber were

married in Vienna

without having received

Leopold's approval,

which arrived grudgingly

the following day. In

the meanwhile the other

movements must have been

completed and sent off,

for on 7 August Mozart

wrote to his father:

'I

send you herewith a

short march

[probably K. 408,

no. 2].

I only hope that all

will reach you in

good time, and be to

your taste. The

first Allegro must

be played with great

fire, the last - as

fast as possible.'

Precisely

when the party

celebrating Haffner's

ennoblement occurred,

and whether the new

symphony was received in

time to be performed on

that occasion, is not

known, for Leopold's

letter reporting the

event is lost. The fact

that in a later letter

Wolfgang was unsure

whether or not

orchestral parts had

been copied (see below)

suggests that the

symphony had not arrived

in time. Be that as it

may, at some time prior

to 24 August, Leopold

must have written his

approval of the work,

for on that day Wolfgang

responded, 'I am

delighted that the

symphony is to your

taste'.

Three months later the

symphony again entered

Mozart's correspondence.

On

4 December he wrote to

his father, in a letter

that went astray, asking

for the score of the

symphony to be returned.

When

it had become clear that

his father had not

received that letter, he

wrote again on the 21st,

summarizing the lost

letter, including, 'If

you find an opportunity,

you might have the

goodness to send me the

new symphony that

I composed for Haffner

at your request. Please

make sure that I have it

before Lent, because I

would very much like to

perform it at my

concert'. On 4 January

he again urged his

father to return the

symphony, stating that

either the score or the

parts would be equally

useful for his purposes.

On the 22nd he again

reminded his father, and

on the 5th of February

yet again with new

urgency; '...as soon as

possible, for my concert

is to take place on the

third Sunday in Lent,

that is, on March 23rd,

and I must have several

copies made, I think,

therefore, that if it is

not copied [into

orchestral parts]

already, it would be

better to send me back

the original score just

as I sent it to you; and

remember to put in the

minuets'. The usually

punctilious Leopold's

delay is mute testimony

to the anger and

frustration he felt over

what he considered to be

his son's foolish choice

of a wife. In any case,

by 15 February Wolfgang

could write, 'Most

heartfelt thanks for the

music you have sent

me... My new Haffner

symphony has positively

amazed me, for I had

forgotten every single

note of it. It must

surely produce a good

effect'.

Mozart then proceeded to

rework the score sent

from Salzburg by putting

aside the march,

eliminating one of the

minuets, deleting the

repeats of the two

sections of the first

movement, and adding

pairs of flutes and

clarinets in the first

and last movements,

primarily to reinforce

the tuttis and requiring

no change in the

existing orchestration

of those movements.

The 'academy' (as

concerts were then

called) duly took place

on Sunday, 23 March, in

the Burgtheatre. Mozart

reported to his father:

'...the

theatre could not

have been more

crowded and... every

box was taken. But

what pleased me most

of all was that His

Majesty the Emperor

was present and,

goodness! - how

delighted he was and how

he applauded me! It

is his custom to

send money to the

box office before

going to the

theatre; otherwise I

should have been

fully justified in

counting on a larger

sum, for really his

delight was beyond

all bounds. He sent

25 ducats.'

In its

broad outlines, Mozart's

report is confirmed by a

review of the concert:

'The

Concert was honoured

with an exceptionally

large crowd, and the

two new concertos and

other fantasies which

Herr Mozart played on

the fortepiano were

received with the

loudest applause. Our

Monarch, who, against

his habit, attended

the whole of the

concert, as well as

the entire audience,

accorded him such

unanimous applause as

has never been heard

of here. The receipts

of the concert are

estimated to amount to

1,600 gulden in all'.

The

programme was typical of

Mozart's 'academies' and

demonstrates the role

that symphonies were

expected to fill as

preludes and postludes

framing an evening's

events:

1. The first 3 movements

of the 'Haffner'

symphony (K. 385)

2. ‘Se il padre perdei'

from Idomeneo

(K. 366)

3. A piano concerto in C

major (K. 415)

4. The recitative and

aria 'Misera, dove son!

- Ah! non son' io che

parlo' (K. 369)

5. A sinfonia

concertante (movements 3

and 4 from the serenade

K. 320)

6. A piano concerto in D

major (K. 175 with the

finale K. 382)

7. ‘Parto m'affretto'

from Lucio Silla

(K. 135)

8. A short fugue

('because the Emperor

was present')

9. Variations on a tune

from Paisiello's I

filosofi

immaginarii (K.

398) and as an encore to

that,

10. Variations on a,

tune from Gluck's La

Rencontre imprévue

(K. 455)

11. The recitative and

rondo 'Mia speranza

adorata - Ah, non sai,

qual pena' (K. 416)

12. The finale of the

'Haffner' symphony (K.

385)

Which of us wouldn’t

give a great deal to be

temporarily transported

in one of science-fiction’s

time machines to the

Burgtheatre on that

Sunday in March 1783 to

hear such a concert led

by Mozart at the

fortepiano?

The 'Haffner' symphony

was among the 6

symphonies that Mozart

planned to have

published in 1784 and in

the following year the

work was indeed brought

out in Vienna by

Artaria, in the

four-movement version

but without the

additional flutes and

clarinets. The fuller

orchestration appeared

in Paris published by

Sieber with a title page

bearing the legend 'Du

repertoire du Concert

spirituel'. (The work

had been given at the

Concert spirituel

apparently on 17 April

1783.) Despite the

symphony's wide

availability, Mozart

included it among pieces

that he sold to Prince

von Fürstenberg

'for performance solely

at his court' in 1786.

Having dwelt at some

length on the history of

the 'Haffner' symphony,

we shall be content to

let the music speak for

itself - which it does

so eloquently - without

further description or

analysis. This recording

is the first to be made

of the original,

Salzburg version of K.

385 and is lacking only

the second minuet and

trio, which are no

longer extant. Mozart

and his father

consistently referred to

this work as a symphony,

even though the

configuration of

movements of this

Salzburg version brings

it into a close

relationship with the

works we know as

orchestral serenades.

Symphony in C major,

K. 425 (’Linz’)

Mozart’s letters in the

months following his

marriage are filled with

promises of a journey to

Salzburg to enable his

father, his sister, and

their friends to meet

his bride. Excuse after

excuse was found to

postpone this trip,