|

|

3 LP's

- D170D3 - (p) 1980

|

|

| 3 CD's -

417 841-2 - (c) 1987 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| The Symphonies

- Vol. 4 - Salzburg 1773-1775 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

58' 40" |

|

| Symphony No. 25

in G Minor, K. 183 / K. 173dB |

27' 53" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro con brio · Andante ·

Menuetto & Trio · Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 29

in A Major, K. 201 / K. 186 |

30' 47" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro moderato · Andante ·

Menuetto & Trio · Allegro con

spirito] |

|

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

53' 17" |

|

| Symphony

No. 30 in D Major, K. 202 / K.

186b |

25' 06" |

|

|

| - [Molto allegro ·

Andantino con moto · Menuetto

& Trio · Presto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

(Serenade) in D Major, K. 203 / K.

189b |

28' 11" |

|

|

| - [Andante

maestoso-Allegro assai · Andante ·

Menuetto & Trio · Prestissimo] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

57' 28" |

|

| Symphony

No. 28 in C Major, K. 200 / K.

189k |

25' 24" |

|

|

| - [Allegro

spiritoso · Andante · Menuetto

(Allegretto) & Trio · Presto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

No. 51 in D Major, K. 121 / K.

207a

|

6' 54" |

|

|

| - [Allegro molto ·

Andante grazioso · Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 204 / K. 213a |

25' 10" |

|

|

| - [Allegro assai ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap Schröder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

The size of the

orchestra used during these

recordings was 9 first

violins, 8 second violins, 4 violas,

3 cellos, 2 double basses, 2 flutes,

2 oboes, 3 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 4

horns and timpani and was made up

from the following players:

|

|

|

|

| Violins

|

Jaap

Schröder

(Antonio Stradivarius, 1709) - Catherine

Mackintosh (Rowland Ross 1978,

Amati) - Simon Standage

(Rogeri, Brescia 1699) - Monica

Huggett (Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Elizabeth

Wilcock (Grancino, Cremona

1652) - Roy Goodman (Rowland

Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - David

Woodcock (Anon., circa 1775) -

Joan Brickley (Mittewald,

circa 1780) - Judith Falkus

(Eberle, Prague, 1733) - Christopher

Hirons (Duke, circa 1775) - John

Holloway (Sebastian Kloz 1750)

- Polly Waterfield (Rowland

Ross 1979 [Amati] & John Johnson

1750) - Micaela Comberti

(Anon., England, circa 1740) - Miles

Golding (Anon., Austria, circa

1780) - Kay Usher (Anon.,

England, circa 1750) - Julie

Miller (Anon., France, circa

1745) - Susan Carpenter-Jacobs

(Franco Giraud 1978 [Amati]) - Robin

Stowell (David Hopf, circa

1780) - Richard Walz (David

Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Judith

Garside (Anon., France, circa

1730) - Rachel Isserlis

(John Johnson 1759)

|

|

|

|

|

| Violas

|

Jan Schlapp

(Joseph Hill 1770) - Trevor Jones

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Katherine

Hart (Charles and Samuel Thompson

1750) - Colin Kitching (Rowland Ross

1978 [Stradivarius]) - Philip Wilby

(Carrass Topham 1974 [Gasparo da Salo]) - Annette

Isserlis (Eberle, circa 1740 & Ian

Clarke 1978 [Guarnieri]) - Simon

Rowland-Jones (Anon., England, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Violoncellos |

Anthony

Pleeth (David Rubio 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Richard Webb

(David Rubio 1975 [Januarius

Gagliano]) - Mark Caudle

(Anon., England, circa 1700) - Juliette

Lehwalder (Jacob Hanyes 1745) |

|

|

|

|

| Double

Basses

|

Barry

Guy (The Tarisio, Gasparo da

Salo 1560) - Peter McCarthy

(David Tecler, circa 1725 &

Anon., England, circa 1770) |

|

|

|

|

Flutes

|

Stephen

Preston (Anon., France, circe

1790) - Nicholas McGegan

(George Astor, circa 1790) - Lisa

Beznosiuk (Goulding, London,

circa 1805) |

|

|

|

|

| Oboes

|

Stanley

King (Jakob Grundmann 1799

& Rudolf Tutz 1978 [Grundmann])

- Clare Shanks (W. Milhouse,

circa 1760) - Sophia McKenna

(W. Milhouse, circa 1760) - David

Reichenberg (Harry Vas Dias

1978 [Grassi]) |

|

|

|

|

Bassoons

|

Jeremy

Ward (Porthaux, Paris, circa

1780) - Felix Warnock

(Savary jeune 1820) - Alastair

Mitchell (W. Milhouse, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Horns

|

William

Prince (Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Keith Maries

(Courtois neveu, circa 1800 &

Anon., Germany (?), circa 1785) - Christian

Rutherford (Courtois neveu,

circa 1800 & Kelhermann, Paris

1810) - Roderick Shaw

(Raoux, circa 1830) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Trumpets

|

Michael

Laird (Laird 1977 [German]) -

Iaan Wilson (Laird 1977

[German]) - Malcom Smith

(Laird 1977 [German]) |

|

|

|

|

| Timpani

|

David

Corkhill (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1890) - Charles Fulbrook

(Hawkes & Son, circa 1890) - David

Stirling (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1890) |

|

|

|

|

| Harpsichord

|

Christopher

Hogwood (Thomas Culliford,

London 1782) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.

Paul's, New Southgate, London

(United Kingdom):

- marzo 1979 (K, 202, 203, 200,

204)

- giugno 1979 (K. 183, 201, 121)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Morten

Winding / John Dunkerley &

Simon Eadon

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - D170D3 (3 LP's) - durata

58' 40" | 53' 17" | 57' 28" - (p)

1980 - Analogico

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 417 841-2 (3 CD's) - durata

58' 40" | 53' 17" | 57' 28" - (c)

1987 - ADD |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

and the symphonic

traditions of his

time by Neal

Zaslaw

Salzburg

and its Orchestra

Some time between 1772 and

1777 the musician and

writer Christian Friedrich

Daniel Schubart visited

Salzburg and reported:

'For several centuries

this archbishopric has

served the cause of music

well. They have a musical

endowment there that

amounts to 50,000 florins

annually, and is spent

entirely in the support of

a group of musicians. The

musical establishment in

their cathedral is one of

the best manned in all the

German-speaking lands.

Their organ is

among the most excellent

that exists: what a pity

that it is not given life

by the hand of a Bach!...

'Their [Vize]kapellmeister

Mozart (the father)

has placed the musical

establishment on a

splendid footing. He

himself is known as an

esteemed composer and

author. His style is

somewhat old-fashioned,

but well founded and full

of contrapuntal

understanding. His church

music is of greater value

than his chamber music.

Through his treatise on

violin playing, which is

written in very good

German and intelligently

organized, he has earned

great honour...

'His son has

become even more famous

than his father. He is one

of the most precocious

musical minds, for as

early as his eleventh year

he had composed an opera

[La finta semplice]

that was well received by

all the connoisseurs. This

son is also one of the

best of our [German]

keyboard players. He plays

with magical dexterity,

and sight-reads so

accurately that his equal

in this regard is scarcely

to be found.

'The choirs in

Salzburg are excellently

organized, but in recent

times the ecclesiastical

musical style has begun to

deteriorate into the

theatrical - an epidemic

that has already infected

more than one church! The

Salzburgers are especially

distinguished in wind

instruments. One finds

there the most admirable

trumpet- and horn-players,

but players of the organ

and other keyboard

instruments are rare. The

Salzburger's spirit is

exceedingly inclined to

low humour. Their folk

songs are so comical and

burlesque that one cannot

listen to them without

side-splitting laughter.

The Punch-and-Judy

spirit shines through

everywhere, and the

melodies are mostly

excellent and inimitably

beautiful'.

(One must keep in mind in

reading this account that

the Archbishop of Salzburg

was both a clergyman and a

temporal ruler; hence the

church and court musicians

were one and the same.)

During the same period

that Schubart visited

Salzburg, Charles Burney

published a report sent

from there in November

1772 by an unidentified

writer who (whatever else

he may have been) was

clearly not an admirer

of Mozart's

orchestral music:

'The archbishop and

sovereign of Saltzburg

[sic] is very

magnificent in his support

of music, having usually

near a hundred performers,

vocal and instrumental, in

his service. This prince

is himself a dilettante,

and good performer on the

violin; he has lately been

at great pains to reform

his band, which has been

accused of being more

remarkable for coarseness

and noise, than delicacy

and high-finishing.

Signor Fischietti, author

of several comic operas,

is at present the director

of this band.

“The Mozart family were

all at Saltzburg last

summer; the father has

long been in the service

of the court, and the son

is now one of the band...

I went to his father's

house to hear him and his

sister play duets on the

same harpsichord... and...

if I may judge of the

music which I heard of his

composition, in the

orchestra, he is one

further instance of early

fruit being more

extraordinary

than excellent'.

Mozart's opinion of the

Salzburg orchestra was far

from enthusiastic. He had

heard the great orchestras

of Mannheim, Turin, Milan,

and Naples, and he knew

that the Salzburg

orchestra, although

moderately large for its

time, was too often

second-rate in its

execution. Writing to his

father from Mannheim in

1778, he compared the

fabulous orchestra there

with their own:

'Ah,

if only we too had

clarinets! You cannot

imagine the glorious

effect of a symphony with

flutes, oboes, and

clarinets. I shall have

much that is new to tell

the Archbishop at my first

audience, and perhaps a

few suggestions to make as

well. Ah, how much finer

and better our orchestra

might be, if only the

Archbishop desired it.

Probably the chief reason

why it is not better is

because there are far too

many performances. I

have no objection to the

chamber music, only to the

concerts

on a larger scale'.

The truth about the

quality of the Salzburg

orchestra undoubtedly

lay somewhere between

Schubart's glowing

appraisal and Mozart's

frequent complaints. As

for its strength, the

official roster of court

musicians published in

the Salzburger Hofkalender

für

1775 shows Joseph

Lolli and Dominicus

Fischietti, both

Kapellmeister, Leopold

Mozart, Vizekapellmeister,

Michael Haydn and

Wolfgang Mozart, both Conzertmeister,

as well as 3 organists,

8 violinists, 1 cellist,

3 double bass players, 2

bassoonists, 3 oboists,

and 3 hunting horn

players. Even a casual

examination of this list

suggests that something

is missing, for Mozart's

Salzburg works often

include parts for

flutes, trumpets, and

timpani, as well as

divided viola parts and

an additional horn. It

appears that several of

these 33 musicians

played more than one

instrument, and there

were others who could be

- and were - called upon

to supplement the

orchestra. These

included the town waits,

the trumpet - and

kettle-drum players of

the Archbishop's army,

and various amateur

performers whose

principal posts at court

were non-musical. Thus

the make-up of the

Salzburg orchestra

varied widely from

season to season and

from occasion to

occasion. As we have

reconstituted the

orchestra for these

recordings, it is as it

may have been heard at

festive occasions during

the year: the strings

9-8-4-3-2, and the

necessary woodwind,

brass, kettle drums and

harpsichord, with 3

bassoons doubling the

bass line whenever

obbligato parts for them

are lacking.

The Symphony as a

Genre

After Beethoven, the

symphony was the most

important large-scale

instrumental genre for

the Romantic composers.

Their conception of the

symphony as an extended

work of the utmost

seriousness, intended as

the centrepiece of a

concert, is very far

from what the musicians

of the second half of

the 18th century had in

mind for their

symphonies. This can be

seen by comparing the

large number of

symphonies turned out

then with the handful

written by the major

19th-century

symphonists. It

can also be seen in the

small number and brevity

of passages devoted to

symphonies in the

newspaper accounts,

memoires and

correspondence of the

period. And it can be

seen in the uses to

which 18th-century

symphonies were put.

'Sinfonia' and

'overtura' or

'ouverture' were

synonymous terms and

concepts then. Planelli

writing in 1772 gave a

typically simple Italian

definition: 'All the

symphonies that serve

[operas] as overtures

are cast from the same

die, and are inevitably

made up of a solemn

grouping of an allegro,

a largo, and a dance'.

The French naturalist

and composer Étienne

de la Ville, Comte de

Lacépède, a

decade later began by

elaborating on

essentially the same

definition: 'A symphony

is ordinarily made up of

3 movements: the first

is more noble, more

majestic, more imposing;

the second slower, more

touching, more pathetic

or more charming; and

the third more rapid,

more tumultuous, more

lively, more animated or

more gay, than the other

two'. He then presented

a characteristic French

notion that a good

symphony must be

dramatic and even

programmatic: ‘The first

movement, that which we

call the allegro

of the symphony, should

present, so to speak,

its overture and the

first scenes; in the andante

or the second movement,

the musician should

place the portrayal of

terrible happenings,

dangerous passions, or

charming objects, which

should serve as the

basis for the piece; and

the last movement, to

which we commonly give

the name presto,

should offer the last

effort of these

frightful or touching

passions. The dénouement

should also be shown

here, and one should see

subsequently the

sadness, fright and

consternation that a

fatal catastrophe

inspires, or the joy,

happiness and ecstasy to

which charming and happy

events give birth...'

Then follow several

pages in this vein,

suggesting how the

scenarios of such

programmatic symphonies

might be handled.

From Germany Schubart

embellished the basic

Italian definition in a

different way: 'This

genre of music

originated from the

overtures of musical

dramas, and came finally

to be performed in

private concerts. As a

rule it consists of an

allegro, an andante, and

a presto. However, our

artists are no longer

bound to this form, and

often depart from it

with great effect.

Symphony in the present

fashion is, as it were,

loud preparation for and

vigorous introduction to

hearing a concert'. In

Mozart's case the most

familiar departure from

the 3-movement

format was the insertion

of a minuet and trio

between the andante and

the finale. This is a

characteristic Austrian

development, and Mozart

not infrequently converted

one of his Italian

symphonies to an Austrian

one by the simple

expedient of adding a

minuet and trio.

Mozart wrote his

symphonies as

curtainraisers to plays,

operas, cantatas,

oratorios, and private and

public concerts. He

sometimes also used them

to end concerts, or even

to begin and end each half

of a long concert. Judging

by the number of

symphonies he wrote in

Salzburg (or those that he

wrote for Italy

and then used in

Salzburg), there must have

been a steady demand for

them there. During the

4-year period 1770-73

alone he wrote 28

symphonies. This

outpouring can be

explained at least in part

by the death of the

Archbishop Sigismund

Christoph von

Schrattenbach in December

1771, which meant that a

period of mourning

prohibited theatrical

entertainments during Fasching

(carnival) and that

concerts would have

provided a substitute form

of entertainment. It also

meant that much new music

would have had to be

provided for the

festivities surrounding

the installation in March

of the new archbishop, the

despised Hieronymus

Joseph

Franz de Paula Graf

Colloredo. A further

explanation for the

surprising number of

symphonies during this

period is that Mozart was

officially promoted from

rank-and-file member of

the orchestra to the

status of Konzertmeister

on August 1772. (Was this

perhaps part of the new

archbishop's 'great pains

to reform his band', which

Burney's informant

mentioned?) Mozart's

efforts to prove himself

worthy of the appointment,

and the responsibilities

of the post once assumed,

may well explain in part

his need to write so many

symphonies. These include

- in addition to those

that, because we know of

no specific occasion for

their creation, we

(rightly or wrongly)

consider to have

originated as concert

symphonies - a number of

other concert symphonies

that Mozart fashioned from

works in other genres.

Among the latter were

opera overtures detached

unchanged from their

operas and put into

circulation, opera

overtures provided with

new finales to bring them

up to the customary 3

movements, and groups of

3, 4, or even 5 movements

drawn from orchestral

serenades.

With the arguable

exception of the last few,

Mozart's symphonies were

perhaps intended to be

witty, charming,

brilliant, and even

touching, but undoubtedly

not profound, learned, or

of great significance. The

main attractions at

concerts were not the

symphonies, but the vocal

and instrumental solos and

chamber music that the

symphonies introduced.

Approaching Mozart's

symphonies with this

attitude in mind relieves

them of a romantic

heaviness under which they

have all too often been

crushed. Thus unburdened,

they sparkle with new

lustre.

Performance Practice

The use of 18th-century

instruments with the

proper techniques of

playing them gives to the

Academy of Ancient Music a

clear, vibrant, articulate

sound. Inner voices are

clearly audible without

obscuring the principal melodies.

Rhythmic patterns and

subtle differences in

articulation are more

distinct than can usually

be heard with modern

instruments. The use of

little or no vibrato

serves further to clarify

the texture. At lively

tempos and with this

luminous timbre, the

observance of all of

Mozart's repeats no longer

makes movements seem too

long. A special instance

concerns the da capos of

the minuets, where, an

ancient oral tradition

tells us, the repeats are

always omitted. But, as we

were unable to trace that

tradition as far back as

Mozart's time, we

experimented by including

those repeats as well.

Missing instruments

understood in 18th-century

practice to be required

have been supplied: these

include bassoons playing

the bass-line along with

the cellos and double

basses, kettle drums

whenever trumpets are

present (except in the

'little' G-minor symphony,

K.183,

where chromaticism renders

their use less idiomatic)

and the harpsichord

continuo. No conductor is

needed, as the direction

of the orchestra is

divided in true

18th-century fashion

between the concertmaster

and the continuo player,

who are placed so that

they can see each other

and are visible to the

rest of the orchestra.

Following 18th-century

injunctions to separate

widely the softest and

loudest instruments, the

flutes and trumpets are

placed at opposite sides

of the orchestra. And the

first and second violins

are placed at the left and

right respectively,

making meaningful the

numerous passages Mozart

wants tossed back and

forth between them.

Musical Sources and

Editions

Until recently

performers of Mozart's

symphonies have relied

upon the editions drawn

from the old complete

works, published in the

19th century by the

Leipzig firm of

Breitkopf & Härtel.

During the past quarter

century, however, a new

complete edition of

Mozart's works (NMA)

has been slowly

appearing, published by

Bärenreiter

of Kassel under the

aegis of the Mozarteum

of Salzburg. The NMA

has been used for almost

all the symphonies from

K.128 to K.551. For the

early symphonies not yet

published in the NMA,

editions have been

created especially for

these recordings,

drawing on Mozart's

manuscripts when they

could be seen, and on

18th- and 19th-century

copies in those cases

where the autographs

were unavailable. (14 of

Mozart's symphonies are

among musical

manuscripts formerly in

the Berlin library but

now being held in Poland

and inaccessible to

Western musicologists.)

A Note

Concerning the

Numbering of Mozart's

Symphonies

The first

edition of Ludwig Ritter

von Köchel's

Chronological-Thematic

Catalogue of the

Complete Works of

Wolfgang Amaadé

Mozart was published

in 1862 (=K1).

It

listed all of the

completed works of Mozart

known to Köchel

in what he believed to be

their chronological order,

from number 1 (infant

harpsichord work) to 626

(the Requiem). The second

edition by Paul Graf von

Waldersee in 1905 involved

primarily minor

corrections and

clarifications. A

thoroughgoing revision

came first with Alfred

Einstein's third edition,

published

in 1936 (=K3).

(A reprint of this edition

with a sizeable supplement

of further corrections and

additions was published in

1946 and is sometimes

referred to as K3a.)

Einstein changed the

position of many works in

Köchel's

chronology, threw out as

spurious some works Köchel

had taken to be authentic,

and inserted as authentic

some works Köchel

believed spurious or did

not know about. He also

inserted into the

chronological scheme

incomplete works,

sketches, and works known

to have existed but now

lost. These Köchel

had

placed in an appendix (=Anhang,

abbreviated Anh.)

without chronological

order. Köchel's

original numbers could not

be changed, for they

formed the basis of

cataloguing for thousands

of publishers, libraries,

and reference works.

Therefore, the new numbers

were inserted in

chronological order

between the old ones by

adding lower-case letters.

The so-called fourth and

fifth editions were

nothing more than

unchanged reprints of the

1936 edition, without the

1946 supplement. The sixth

edition, which appeared in

1964 and was edited by

Franz Giegling, Alexander

Weinmann, and Gerd Sievers

(=K6),

continued Einstein's

innovations by adding

numbers with lower-case

letters appended, and a

few with upper-case

letters in instances in

which a work had to be

inserted into the

chronology between two of

Einstein's lowercase

insertions. (A so-called

seventh edition is an

unchanged reprint of the

sixth). Hence, many of

Mozart's works bear two K

numbers, and a few have

three.

Although it was not Köchel's

intention in devising his

catalogue, Mozart's age at

the time of composition of

a work may be calculated

with some degree of

accuracy from the K

number. (This works,

however, only for numbers

over 100). This is done by

dividing the number by 25

and adding 10. Then, if

one keeps in mind that

Mozart was born in 1756,

the year of composition is

also readily approximated.

The old Complete Works of

Mozart published 41

symphonies in 3 volumes

between 1879 and 1882,

numbered 1 to 41 according

to the chronology of K1.

Additional symphonies

appeared in supplementary

volumes and are sometimes

numbered 42 to 50,

even though they are early

works.

Bibiography

- Anderson,

Emily: The Letters

of Mozart & His

Family (London,

1966)

- Burney,

Charles: The

Present State of

Music in Germany,

The Netherlands, and

United Provinces

(London, 1773)

- Della

Croce, Luigi: Le

75 sinfonie de

Mozart (Turin,

1977)

- Eibl,

Joseph Heinze, et al.:

Mozart: Briefe und

Aufzeichnungen

(Kassel, 1962-75)

- Koch,

Heinrich: Musilcalisches

Lexikon

(Frankfort, 1802)

- Landon,

H. C. Robbins: 'La

crise romantique dans

la musique

autrichienne vers

1770: quelques

précurseurs inconnus

de la Symphonie en sol

mineur (KV 183) de

Mozart', Les

influences étrangères

dans l'oeuvre de W.

A. Mozart

(Paris, 1958)

- Larsen,

Jens

Peter: 'A Challenge to

Musicology: the

Viennese Classical

School', Current

Musicology

(1969), ix

- Mahling,

Christoph-Hellmut:

'Mozart und die

Orchesterpraxis seiner

Zeit', Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1967)

- Mila,

Massimo: Le

Sinfonie de Mozart

(Turin, 1967)

- Saint-Foix,

Georges de: Les

Symphonies de Mozart

(Paris, 1932)

- Schneider,

Otto, and Anton

Algatzy: Mozart-Handbuch

(Vienna, 1962)

- Schubart,

Ludwig: Christ, Fried.

Dan. Schubart's

Ideen zu einer

Asthetik der

Tonkunst

(Vienna, 1806)

- Schultz,

Detlef: Mozarts Jugendsinfonien

(Leipzig, 1900)

- Sulzer,

Johann

Georg: Allgemeine

Theorie der schönen

Künste

(Berlin, 1771-74)

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'The Compleat

Orchestral Musician',

Early Music

(1979), vii/1

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'Toward the

Revival of the

Classical Orchestra',

Proceedings of the

Royal Musical

Association

(1976-77), ciii

Copyright

© 1979 by Neal

Zaslaw

|

|

The

Symphonies of 1773-75

The 7

symphonies presented

here, written between

the time that Mozart was

17 years, 8 months old

and the time that he was

19 years, 6 months, may

be divided into 3 kinds:

4 Germanic

concert-symphonies with

minuets and repeated

sections in all

movements, each lasting

more than 25 minutes (K.

183, 200, 201, 202) ; 2

symphonies in a format

similar to the previous

4 but drawn from

orchestral serenades (K.

203, 204) ; and 1

Italianate

overture-symphony,

without a minuet and

without repeated

sections, lasting around

7 minutes, created from

an opera overture (K.

121). None of these

symphonies were printed

during Mozart's

lifetime, although 2 of

them (K. 182, 202) were

brought out as early as

1798-99.

Mozart visited

Vienna from the middle

of July

until the end of

September 1773; the

autograph manuscript of

the G-minor symphony, K.

183, is dated 5 October

1773. This symphony and

3 others (K. 201, 202,

200) are longer and more

serious than any of

Mozart's previous

symphonies, and most

commentators suggest

that this must have been

the result of the

Viennese visit. (In case

we wonder what it was

that Mozart heard in

Vienna, Charles Burney,

who spent some weeks

there in 1772, tells us

that the Viennese

composers who were

distinguishing

themselves at that time

were Hasse, Gluck,

Gassmann, Wagenseil,

Salieri, Hoffman, Haydn,

Dittersdorf, Vanhal, and

Huber.) We do not know

of particular occasions

for which any of this

tetralogy may have been

composed.

A trip to Munich to

attend the rehearsals

and performance of La

finta giardiniera

lasted from 6 December

1774 until 7 March 1775.

This journey seems to

have had an effect quite

opposite to that of the

journey to Vienna, for

afterwards Mozart

composed no further

original symphonies

prior to his visit to

Paris in 1778. This is

especially surprising in

the light of the fact

that on 16 November 1775

the Archbishop of

Salzburg opened a new

theatre, the existence

of which surely created

a demand for music to

grace the plays

presented there. It may

be an indication of

Mozart's profound

disillusionment with

Salzburg at the time

that he failed to

respond to this

opportunity.

Symphony in G minor,

K. 173dB [K.183]

Debussy once wrote of

Beethoven's Ninth

Symphony that it "has

long been surrounded by

a haze of adjectives.

Together with the Mona

Lisa's smile - which for

some strange reason has

always been labelled

"mysterious" - it is the

masterpiece about which

the most stupid comments

have been made. It's a

wonder it hasn't been

submerged entirely

beneath the mass of

words it has excited".

On a more modest scale

the same could be said

of much of the verbiage

surrounding Mozart's two

G-minor symphonies - the

famous one, K. 550, and

the so-called "Little" G

minor presented here. In

this case the adjectival

excesses are at least in

part due to the fact

that the vast majority

of 18th-century

symphonies are in major

keys and appear to

convey the optimistic

"greatness, solemnity

and stateliness"

mentioned by Kimberger,

rather than the darker,

more passionate feelings

of the G-minor works. In

addition, these excesses

result from a

melioristic view of the

history of music, which

regards Mozart's

minor-key symphonies as

adumbrations, mere

forerunners, of the

monumental symphonic

masterpieces of the

Romantic era. We are

assured by adherents to

this school of thought

that K. 183 is pre- or

proto-Romantic, that it

is the result of "the

romantic crisis in

Austrian music around

1770", and that it is a

manifestation of the

cultural trend which has

been dubbed Sturm

und Drang. This

"haze of adjectives" can

be at least partially

dissipated by attempting

to view K. 183 looking

forward from the first

two-thirds of the 18th

century, rather than

backwards from the 19th.

The contribution to the

history of music made by

the generation between

that of J.

S. Bach and that of

Wolfgang Mozart was to

create lighter, shorter,

and simpler musical

styles and genres - to

move away from the

seriousness and

monumentality of some of

the music of the

previous generation.

This lightening of

spirit is nicely

captured by the

difference between

Andreas Werckmeister's

late 17th-century

definition of music as

"a gift of God, to be

used only in His honour"

and Charles Burney's

mid-18th-century

statement, "Music is an

innocent luxury,

unnecessary, indeed, to

our existence".

The "romantic crisis"

theory is based upon the

intriguing observation

that, whereas the

symphonies of the late

1750s and

early 1760s largely

avoided the minor keys,

in the late 1760s and

early 1770s there was a

sudden production of

minor-key symphonies in

Austria by (in addition

to Mozart) Dittersdorf,

J.

Haydn, Vanhal, and Ordoñez.

Landon points out that

in contrast to most

symphonies of the

previous decade these

works have in common

more frequent use of

cotmterpoint, themes

incorporating wide

leaps, greater use of

syncopations, more

extended finales, and

more frequent occurrence

of unison passages.

(Note that - as we have

seen - virtually all of

these traits were, only

a few years later,

considered by Kirnberger

to be the normal

attributes of any

concert symphony and not

just those in minor

keys.) Unfortunately for

this theory, not a

single word occurs in

the correspondence,

diaries, or periodicals

of the period suggesting

a "romantic crisis". And

as each of the composers

mentioned wrote only 1,

2 or 3 such symphonies,

the "crisis" must have

been rapidly overcome,

certainly more quickly

and less expensively

than any cure ever

effected by

psychoanalysis.

As for Sturm und

Drang, of the key

literary works of that

"movement", Goethe's

novel Werther

dates from 1774 and

Klinger's play Sturm

und Drang from

1776, while the works in

the visual arts usually

considered

representative of "storm

and stress" - by H. Füssli,

F. Müller, J.

A. Carstens, F. Kobell,

J.

C. Reinhart, W.

Tischbein, and others -

date from even later.

Hence we are being asked

to imagine that the

prescient Austrian

musicians participated

in a cultural movement

that had yet to come

into existence. To dub

the generation that

included Bach's sons,

Mozart's father, and

Gluck (as well as

Vanhal, Ordoñez

and Dittersdorf)

"forertmners" is

antihistorical. These

talented composers did

not rise from their beds

each morning in

order to "forerun";

rather they composed

music that was

thoroughly modem and

that appealed to them

and to their

contemporaries. At first

they must have been

enchanted by the new,

light, galant style they

had helped to create.

Later perhaps, the

novelty of these sounds

and forms began to wear

off, and the musicians

sought to reintroduce

certain serious elements

of the Baroque while

maintaining other

aspects of the new

style. This stylistic

evolution is hardly a

"crisis" therefore, but

rather, as Larsen has

pointed out, "the

breakthrough of the

Classical style - the

final synthesis". This

synthesis occured in

major - as well as

minor-key works, but it

was the sombre

chromaticisms of the

latter which appealed to

Romantic critics, and it

is those works that

continue to call forth a

“haze of adjectives".

The marvellous sounds of

the minor-key symphonies

of the early 1770s were

not entirely new ones.

The opera house had long

required these

tempestuous effects to

portray nature's storms

as well as storms of

human emotion. Young

Mozart knew of them long

before he composed K.

183, for the D-minor

"sinfonia" of 1771, K.

118/74c (recorded in Box

2), is in a similar

vein, and, even more

extraordinarily, while

staying in Chelsea in

1764 he sketched into a

notebook a G-minor

keyboard piece, K. 15p,

in a quasi-orchestral

style, which already

captured the stormy

character that has been

erroneously claimed as

the invention of a later

period.

The Symphony's opening

allegro con brio in

common time and its

closing allegro in alla

breve, in addition to

their notoriously stormy

character, exhibit

large-scale sonata-form

movements with both

halves repeated and the

whole terminated by a

coda. The andante in 2/4

in E-flat major is also

in sonata form with both

halves repeated, but

without coda. Here

stormy emotions give way

to other passions,

portrayed by the

appoggiaturas of longing

and sadness. These are

tossed back and forth

between the muted

violins and the

obbligato bassoons, and

are heard in the violas,

cellos and basses as

well. An especially fine

moment occurs 8 bars

into the recapitulation,

where, in a passage not

present in the

exposition, a rising

sequence of sighs

touches upon F minor, G

minor, C minor, A-flat

major, E-flat major, and

B-flat major in rapid

succession.

Mozart originally had

begun the andante

differently but when he

had got no further than

this he must have

realized that something

was amiss (the halting

quality of the repeated

E-flats?), and he

started again with the

same initial three-note

motive carried through

in a more convincing

manner.

The minuet's stern

unisons and touches of

chromaticism contradict

all of our received

ideas about the polite

social graces of that

dance, and illustrate an

extreme example of

Koch's remarks that

"because minuets of this

type are really not for

dancing, composers have

departed from the

original conception..."

Here the four-bar

phrases and the rounded

binary form are

traditional but the

demeanour is no longer

that of a ball-room

dancer. This disparity

between what we expect

in a minuet and what

Mozart has given us is

emphasized by the

G-major trio, which is

written for Harmonie

- that is, for the

favourite Austrian

wind-band consisting of

pairs of oboes, horns,

and bassoons. The Harmonie

trio offers a breath of

fresh air and

relaxation, as it were,

placing into even

sharper relief the

character of the minuet

that flanks it.

Such wind groups

(sometimes joined by a

pair of clarinets or

English horns and

occasionally reinforced

in the bass by a

contrabass viol,

contrabassoon or

serpent) were much

employed in and around

Vienna to provide music

for banquets,

out-of-doors social

occasions, evening

serenades, and so on.

Such a group provided

Burney with dinner music

during his stay at the

Viennese Gasthof

"At the Sign of the

Golden Ox", and

a decade later Mozart

was to write a beautiful

serenade (K. 375) for

wind sextet and then be

pleasantly surprised by

itinerant musicians playing

it under his window on

his name day.

Symphony in A

major, K.186a [K.201]

The autograph manuscript

of this work is dated 6

April 1774. Much of what

was stated about the

previous symphony could

be repeated about this

one, including the

agitated and serious

character of the first

and last movements, the

use of sonata form in 3

of the 4 movements, the

contrasted character of

the andante (in this

case noble serenity

rather than longing),

the symphonic rather

than dance quality of

the minuet, and so on.

The thoroughgoing

excellence of this

symphony has long been

recognised, and it and

the previous work are

the only symphonies from

this period that have

entered the regular

repertories of many of

the major symphony

orchestras.

The first movement

begins piano, without

the more usual loud

chords or fanfare. The

opening theme consists

of an octave drop and a

group of forward-moving

quavers leading to the

next octave drop, and so

on in a rising sequence,

the whole being repeated

an octave higher, tutti,

and in canon between the

violins and the lower

strings. Several

attractive subjects of

contrasted character

appear in the dominant,

leading to a vigorous

closing section filled

with repeated notes and

arpeggios. The compact

development section,

bustling with scale-wise

passages, repeated

notes, modulations and

syncopations, leads to a

literal recapitulation.

Both halves are

repeated, and the coda,

based upon the opening

theme in canon, brings

the finely-crafted

movement to a jubilant

close.

The andante and minuet

have in common the

prominent use of dotted

and double-dotted

rhythms. Such rhythms,

characteristic of

marches and of the slow

sections of French ouvertures,

were thought to convey

stateliness, nobility

and even godliness, and

were used for that

purpose in numerous

18th-century operas and

oratorios.

Despite its

fully-worked-out sonata

form including a

development section that

Einstein described as

"the richest and most

dramatic Mozart had

written up to this

time", the finale has

the character of a chasse.

That is to say, it is a

piece based upon the

spirit of the hunt and

replete with repeated

notes and other

fanfare-like motives

idiomatic to hunting

horns. (Listeners

familiar with the

finales of Mozart's horn

concertos will know what

is meant by this.) At

the ends of the

exposition, the

development, the

recapitulation and the

coda, Mozart gives the

violins a rapid

ascending scale. One

could hardly ask for

clearer aural signposts

to articulate the formal

structure of the

movement.

We are amusingly

reminded of the perils

of ascribing intentions

to composers in their

abstract instrumental

music by the fact that

while the British

biographer of Mozart,

Dyneley Hussey, is quite

certain that this

symphony is imbued with

"tragic nobility", Otto

Jahn

has no doubt whatever

that it is "full of

cheerful humour from

beginning to end".

Symphony in D major,

K.186b [K.202]

In this symphony, dated

5 May 1774, St. Foix and

other commentators

detect a retrenchment, a

return to the sheer

entertainment and galanterie

of the earlier

symphonies after the

exceptional seriousness

of the symphonies K. 182

and 183. Whether this is

a cause for regret or

pleasure depends upon

one's aesthetic; for St.

Foix it was the former.

But why should a festive

work in D major with

trumpets be “serious"?

Who knows what gala

occasion in Salzburg may

have required just such

music as this?

The first movement is a

tightly-knit sonataform

movement with

interesting manipulation

of the common-coin trill

figure which

occurs unobtrusively on

D in the fourth bar,

with more emphasis on E

some 21 bars later, then

11 bars after that with

considerable force on A

as an interruption of a

lyrical theme, and

finally invades the

texture toward the end

of the exposition,

sounding for all the

world like a hive of

bumblebees trying to

sing polyphony.

The andantino con moto,

in diminutive sonata

form and for strings

alone, masks by the

apparent simplicity of

its graceful cantabile

melodies the great care

Mozart took to make all

four voices active and

interesting.

The minuet exudes the

spirit of the ball room,

but if we compare it

with the 16 minuets, K.

176, which Mozart wrote

for the carnival of

1774, we see at once

some striking

differences: the actual

ball-room minuets are

shorter, more

homophonic, and always

omit violas. Apparently

the simpler textures and

more foursquare phrase

structures of K. 176

were designed to be

easily perceptible in a

noisy social setting,

whereas the more

elaborate symphony

minuet was meant to have

closer attention paid

it.

The presto, which begins

with an idea derived

from the opening of the

first movement, is also

in sonata form with both

halves repeated and a coda.

The movement displays an

attractive mixture of

serious and

not-so-serious ideas.

The opening fanfare in

dotted rhythms is in the

spirit of a "quick

step". This march is

however contrasted with

patches of lyricism. And

if the development

section, with its

diminished chords and

abrupt pauses, causes us

momentarily to be quite

serious, then the

delightful way in which

the coda simply

evaporates rather than

offering a "proper"

ending reminds us that

the composer was an

18-year-old with a

well-developed sense of

humour.

Symphony in D major,

K.189b [K.203]

This symphony was

extracted from an

orchestral serenade.

That was a perfectly

logical procedure given

that the occasions for

serenades and symphonies

were different and that

the serenades were cast

in a composite form made

up of symphony and

concerto movements

prefaced by a march.

Salzburg serenades were

usually written either

for such private

occasions as parties

celebrating weddings,

birthdays or name-days,

and investitures, or for

the public celebrations

of the end of the summer

term at Saltzburg

University. Symphonies,

as we have seen, were

generally for the

church, theatre, or

concert hall. Mozart

found a means of making

one work serve two

purposes.

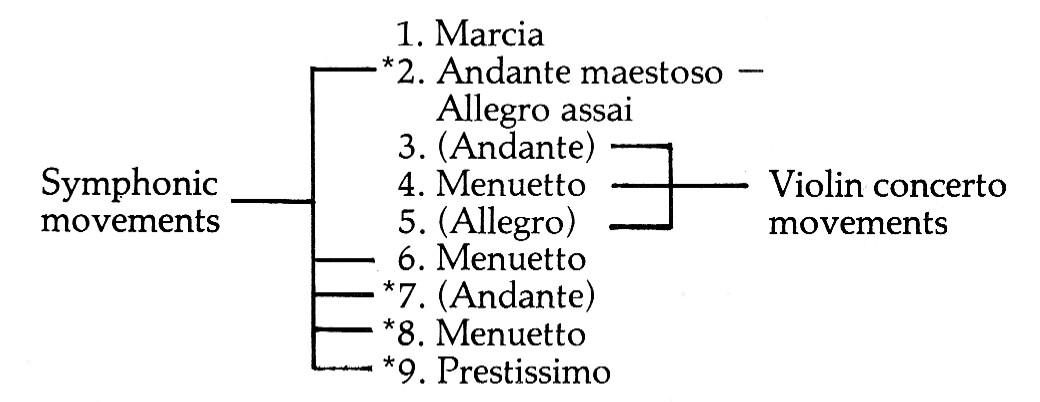

In the present case the

interpenetration of the

two genres is as follows

(movements used in the

symphony are starred):

This

is one of 5 Mozart

serenades that exist

in symphony versions.

In 3 of the 5

instances there are

sets of orchestral

parts at least

partially in Leopold

or Wolfgang Mozart's

hand, making clear

that they themselves

were involved in the

metamorphosis from

serenade to symphony.

In

the remaining 2

cases (including the

present one) we have

only copyists'

manuscripts, but there

seems every reason to

suspect that those may

stem from originals

coming from Mozart or

his circle.

The serenade from

which this symphony is

drawn was composed in

Salzburg in August

1774. The

stately introduction to

the first movement is a

feature found only in a

handful of Mozart's late

symphonies, other than

in those originating as

Serenades. (Haydn was

much fonder than Mozart

of this way of beginning

symphonies.) Perhaps

Mozart was slow to

appreciate the

possibilities of the

slow introduction, for

in 1777 in a letter to

his father he criticized

the Mannheim symphonists

for beginning "always in

the same manner, with an

introduction in slow

time and in unison". The

practice may be a

vestige of the French

baroque ouverture,

which customarily began

with a noble grave

section leading into a

longer one in a rapid

tempo. Whatever its

origins, the 7-bar

andante maestoso here

serves to set off the

allegro assai that

follows just as the cool

shine of a gold setting

shows off the brilliant

sparkle of a diamond.

The allegro assai itself

is a sonata-form

movement in common time

with both halves

repeated. It

contains a couple of

especially lovely

lyrical themes

contrasting with the

general bustle of the

movement, and has a

stormy,

contrapuntally-conceived

development section.

The andante in 2/4 that

follows is also in

sonata form. The violins

are muted, with the

cantabile melody of the

firsts accompanied by

the whirring

demisemiquaver figures

of the seconds. A solo

oboe makes its plaintive

appearance in each half

of the movement as well

as in the coda. This

pastoral tranquillity is

broken only by 3

fortissimo unison

outbursts in the

development section,

each serving to announce

the sudden arrival at a

new key.

The minuet sparkles with

pomp and circumstance

(though hardly of the

Elgarian variety) while

the trio, in which the

solo oboe reappears, is

as simple as the minuet

is pompous. The stately

and festive style of the

minuet combined

with its repeated use of

the rhythm give it the

character of a

polonaise.

The

prestissimo, in 2/4 and

again in sonata form

with both halves

repeated and a coda,

goes by so rapidly that

it can hardly be

believed that, counting

repeats, this finale is

some 538 bars long! The

marvellous gestures in

the exposition and

recapitulation, where

the orchestra lands on

and holds a

chromatically altered

note, are reminiscent of

some of the quirkier

moments in C. P. E.

Bach's symphonies, even

though the rest of the

movement would appear to

be under the more

southerly influence of

opera buffa.

Symphony in C major,

K.189k [K.173e

- K.200]

This work is

dated 17 November 1774

according to the sixth

edition of the Köchel

catalogue and according

to Landon, but as

someone attempted to

obliterate the date, it

is difficult to read.

The Köchel

catalogue admits that it

could be read as 12

November, and Einstein

deciphered the year as

1773. If the

date 17 November 1774 is

correct, then this

symphony brings to an

end the great burst of

symphonies composed by

Mozart for Salzburg in

the early 1770s. After

this he was not to write

another symphony proper

until the great "Paris"

symphony of 1778. (The 4

additional symphonies

found in our chronology

between this work and

the 'Paris' symphony are

reworkings of serenades

or of opera overtures.)

As this work is in a

format very similar to

those of the previous

few symphonies, we may

forego a

movement-by-movement

description in order to

take note of the fact

that several

commentators have heard

echoes of other music in

this piece. Wyzewa and

St. Foix hear J.

Haydn's influence in the

first movement. Abert

points to the similarity

between this movement

and the first movement

of the B-flat symphony,

K.182/173dA. Wyzewa and

St. Foix judge the

opening idea of the

andante to be in the

style of a German

popular song. They

consider the minuet

"like a first draft of

the minuet from the

"Jupiter" symphony".

(The present writer,

however, finds the

opening of the minuet

closer to that of the

minuet of Haydn's

"Farewell" symphony, no.

45.) ln the finale

Hocquard is reminded of

The Magic Flute,

finding here what he

calls “the Monostatos

motive".

This game of "find the

tune" and "locate the

influence" is difficult

to resist and, as

several major studies

have been devoted

largely to it, we should

try to understand what

lies behind it.

Composers of the period

in question were not so

interested in

originality per se as

were those of a later

period. Rather than

originality they sought

suitability. Or, to put

it another way, more

attention was paid to

craft and less to

inspiration. The

greatest works could be

based upon the most

common materials. We may

compare this to the

attitude of a fine

cabinet maker

commissioned to build a

table. His choice of

materials (wood) and

shape (rectangular) need

not be novel for the

table to be beautiful to

look at and

well-functioning to use,

provided he knows how to

pick the right wood and

what to do with that

wood.

Symphony in D major,

K.207a [K.196-121]

Mozart's comic opera La

finta giardiniera (“The

pretended

gardener-girl"),

K.196,was first

performed in Munich on

13 January

1775, that is, during

carnival. At some later

date he composed a 3/8

finale to turn the

2-movement overture into

a 3-movement symphony.

There is every reason to

hypothesize that the

finale was added in

Salzburg in 1775,

although the manuscript

is undated. Unlike the

previous 5 symphonies,

which were Germanic

concert-symphonies with

minuets, repeated

sections in all

movements, and lasting

around 25 minutes, this

symphony is an Italianate

overture-symphony

without minuet or

repeated sections and

lasting one quarter as

long. A brief plot

summary of La finta

giardiniera will

serve to suggest why the

first movement is so gay

and the second movement

so galant. (The finale,

a bright jig, picks up

where the opening

movement left off, as

far as its spirit is

concerned.)

David Ewen summarizes

the tangles of La

finta giardiniera's

love-intrigues thus:

Marchesa Violante has

been slighted by the man

she loves, Count

Belfiore. She and her

valet disguise

themselves as gardeners

and seek employment at

the palace of the Podestà,

ruler of Lagonero. The Podestà

finds Violante most

charming; and the Podestà's

maid is strongly

attracted to the valet.

Meanwhile, Count

Belfiore is about to

marry the Podestà's

niece who, in turn, is

being pursued by Ramiro.

Thus the various

love-plot threads become

hopelessly entangled.

Before the final

curtain, however,

Violante and the Count,

the valet and the maid,

and Ramiro and the

Podestà's

niece are joined

together in pairs by

mutual love. Only the

Podestà

himself remains without

a mate.

Mozart's symphony is of

course not programmatic.

But it was his practice

to write the overture of

an opera late in the

proceedings and

certainly long after he

had familiarized himself

with the story, and, as

Kirnberger tells, us, an

overture-symphony must

“have a character that

puts the listener in the

proper frame of mind for

the piece to follow".

Symphony in D major,

K.213A [K.204]

Like the symphony K .

203/189b discussed

above, this work is

drawn from an orchestral

serenade and comprises

(not counting the march)

movements 1, 5, 6 and 7

of the larger work. The

autograph manuscript of

the serenade reads "li 5

d'agosto 1775", and the

work is believed to have

been written to provide

a musical finale to

ceremonies marking the

end of the term at the

University of Salzburg.

The symphony version

appears to have been

better known than the

serenade itself and

survives in a number of

later-18th and

early-19th-century

manuscripts. One of

these, a set of

orchestral parts with

corrections in Mozart's

hand, was in his

possession at the time

of his death. In a

letter to his father of

4 January

1783 Mozart had asked to

be sent this symphony,

and the urgency of his

request makes it clear

that he was intending to

perform it in Vienna.

The allegro assai, an

energetic sonata-form

movement, begins with 3

tutti chords. Such

beginnings were believed

to have been the

invention of Lully, who

wanted to show off the

good ensemble of his

orchestra from the very

first chord. This was

the famous premier

coup d'archet.

After arriving in Paris

in 1778, Mozart made fun

of this notion in a

letter to his father:

"What a fuss the oxen

here make of this trick!

The devil take me if I

can see any difference!

They all begin together,

just as they do in other

places". The andante

which follows shows

clearly its serenade

origins in the lovely

concertante writing for

a flute, an oboe, a

bassoon, and a pair of

homs. The solo flute

also reappears in the

trio of the minuet. The

finale has an

idiosyncratic structure

alternating between an

andantino grazioso in

2/4 and an allegro in

3/8, with each appearing

4 times. This

interesting experiment

was repeated by Mozart

only two months later in

the finale of his violin

concerto, K.218, in

which an andante

grazioso in 2/4 and an

allegro ma non troppo in

6/8 alternate 5 times.

The finale of the violin

concerto is marked

"rondeau", and this

gives us a clue to the

interpretation of the

finale at hand: it is an

original sort of rondo

structure, handled with

aplomb and a touch of

wit.

©

1980 by Neal

Zaslaw

|

|

|

|

|