|

|

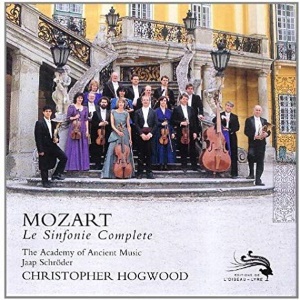

3 LP's

- D169D3 - (p) 1979

|

|

| 3 CD's -

417 592-2 - (c) 1987 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| The Symphonies

- Vol. 3 - Salzburg 1772-1773 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

51' 52" |

|

| Symphony No. 18

in F Major, K. 130 |

21' 17" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andantino grazioso ·

Menuetto & Trio · Molto allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 50

in D Major, K. 161/3 / K. 163 / K.

141a |

7' 48" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro moderato · Andante ·

Presto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 19 in E flat Major, K. 132 |

22' 47" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante · Menuetto &

Trio · Allegro · Anhang:

Andantino grazioso] |

|

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

55' 18" |

|

| Symphony

No. 20 in D Major, K. 133 |

28' 02" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 21 in A Major, K. 134 |

19' 22" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 135 |

7' 54" |

|

|

| - [Molto allegro ·

Andante · Molto allegro] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

55' 01" |

|

| Symphony

No. 26 in E flat Major, K. 184 /

K. 161a |

8' 31" |

|

|

| - [Molto presto ·

Andante · Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 27 in G Major, K. 199 / K.

161b |

20' 23" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andantino grazioso · Presto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 22 in C Major, K. 162 |

9' 19" |

|

|

| - [Allegro assai ·

Andantino grazioso · Presto assai] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 23 in D Major, K. 181 / K.

162b |

8' 00" |

|

|

| - [Allegro

spiritoso · Andantino grazioso ·

Presto assai] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 24 in B Major, K. 182 / K.

173dA |

8' 48" |

|

|

| - [Allegro

spiritoso · Andantino Grazioso ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap Schröder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

The size of the

orchestra used during these

recordings was 9 first

violins, 8 second violins, 4 violas,

3 cellos, 2 double basses, 2 flutes,

2 oboes, 3 bassoons, 2 trumpets, 4

horns and timpani and was made up

from the following players:

|

|

|

|

| Violins

|

Jaap

Schröder

(Antonio Stradivarius, 1709) - Catherine

Mackintosh (Rowland Ross 1978,

Amati) - Simon Standage

(Rogeri, Brescia 1699) - Monica

Huggett (Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Elizabeth

Wilcock (Grancino, Cremona

1652) - Roy Goodman (Rowland

Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - David

Woodcock (Anon., circa 1775) -

Joan Brickley (Mittewald,

circa 1780) - Alison Bury

(Anon., England, circa 1730) - Judith

Falkus (Eberle, Prague, 1733)

- Christopher Hirons (Duke,

circa 1775) - John Holloway

(Sebastian Kloz 1750) - Polly

Waterfield (Rowland Ross 1979

[Amati] & John Johnson 1750) - Micaela

Comberti (Anon., England,

circa 1740) - Miles Golding

(Anon., Austria, circa 1780) - Kay

Usher (Anon., England, circa

1750) - Julie Miller (Anon.,

France, circa 1745) - Susan

Carpenter-Jacobs (Franco

Giraud 1978 [Amati]) - Robin

Stowell (David Hopf, circa

1780) - Richard Walz (David

Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Judith

Garside (Anon., France, circa

1730) - Rachel Isserlis

(John Johnson 1759)

|

|

|

|

|

| Violas

|

Jan Schlapp

(Joseph Hill 1770) - Trevor Jones

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Katherine

Hart (Charles and Samuel Thompson

1750) - Colin Kitching (Rowland Ross

1978 [Stradivarius]) - Nicola Cleminson

(McDonnel, Ireland, circa 1760) - Philip

Wilby (Carrass Topham 1974 [Gasparo da

Salo]) - Annette Isserlis (Eberle,

circa 1740 & Ian Clarke 1978

[Guarnieri]) - Simon Rowland-Jones

(Anon., England, circa 1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Violoncellos |

Anthony

Pleeth (David Rubio 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Richard Webb

(David Rubio 1975 [Januarius

Gagliano]) - Mark Caudle

(Anon., England, circa 1700) - Juliette

Lehwalder (Jacob Hanyes 1745) |

|

|

|

|

| Double

Basses

|

Barry

Guy (The Tarisio, Gasparo da

Salo 1560) - Peter McCarthy

(David Tecler, circa 1725 &

Anon., England, circa 1770) |

|

|

|

|

Flutes

|

Stephen

Preston (Anon., France, circe

1790) - Nicholas McGegan

(George Astor, circa 1790) - Lisa

Beznosiuk (Goulding, London,

circa 1805) |

|

|

|

|

| Oboes

|

Stanley

King (Jakob Grundmann 1799

& Rudolf Tutz 1978 [Grundmann])

- Clare Shanks (W. Milhouse,

circa 1760) - Sophia McKenna

(W. Milhouse, circa 1760) - David

Reichenberg (Harry Vas Dias

1978 [Grassi]) |

|

|

|

|

Bassoons

|

Jeremy

Ward (Porthaux, Paris, circa

1780) - Felix Warnock

(Savary jeune 1820) - Alastair

Mitchell (W. Milhouse, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Horns

|

William

Prince (Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Keith Maries

(Courtois neveu, circa 1800 &

Anon., Germany (?), circa 1785) - Christian

Rutherford (Courtois neveu,

circa 1800 & Kelhermann, Paris

1810) - Roderick Shaw

(Raoux, circa 1830) - John

Humphries (Halari, circa 1825)

|

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Trumpets

|

Michael

Laird (Laird 1977 [German]) -

Iaan Wilson (Laird 1977

[German]) |

|

|

|

|

| Timpani

|

David

Corkhill (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1890) - Charles Fulbrook

(Hawkes & Son, circa 1890) |

|

|

|

|

| Harpsichord

|

Christopher

Hogwood (Thomas Culliford,

London 1782) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.

Paul's, New Southgate, London

(United Kingdom):

- settembre 1978 (K. 130, 161,

132, 133, 134, 162)

- marzo 1979 (K, 184, 199, 181,

182)

- giugno 1979 (K. 135)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Peter

Wadland & Morten Winding /

John Dunkerley & Simon Eadon

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - D169D3 (3 LP's) - durata

51' 52" | 55' 18" | 55' 01" - (p)

1979 - Analogico

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 417 592-2 (3 CD's) - durata

51' 52" | 55' 18" | 55' 01" - (c)

1987 - ADD |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

L'Edizione

in 3 CD's (417 592-2) è

diversamente miscelata rispetto

all'originale pubblicazione in LP:

contiene infatti anche la Sinfonie

K. 185 (K. 167a). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

and the symphonic

traditions of his

time by Neal

Zaslaw

Salzburg

and its Orchestra

Some time between 1772 and

1777 the musician and

writer Christian Friedrich

Daniel Schubart visited

Salzburg and reported:

'For several centuries

this archbishopric has

served the cause of music

well. They have a musical

endowment there that

amounts to 50,000 florins

annually, and is spent

entirely in the support of

a group of musicians. The

musical establishment in

their cathedral is one of

the best manned in all the

German-speaking lands.

Their organ is

among the most excellent

that exists: what a pity

that it is not given life

by the hand of a Bach!...

'Their [Vize]kapellmeister

Mozart (the father)

has placed the musical

establishment on a

splendid footing. He

himself is known as an

esteemed composer and

author. His style is

somewhat old-fashioned,

but well founded and full

of contrapuntal

understanding. His church

music is of greater value

than his chamber music.

Through his treatise on

violin playing, which is

written in very good

German and intelligently

organized, he has earned

great honour...

'His son has

become even more famous

than his father. He is one

of the most precocious

musical minds, for as

early as his eleventh year

he had composed an opera

[La finta semplice]

that was well received by

all the connoisseurs. This

son is also one of the

best of our [German]

keyboard players. He plays

with magical dexterity,

and sight-reads so

accurately that his equal

in this regard is scarcely

to be found.

'The choirs in

Salzburg are excellently

organized, but in recent

times the ecclesiastical

musical style has begun to

deteriorate into the

theatrical - an epidemic

that has already infected

more than one church! The

Salzburgers are especially

distinguished in wind

instruments. One finds

there the most admirable

trumpet- and horn-players,

but players of the organ

and other keyboard

instruments are rare. The

Salzburger's spirit is

exceedingly inclined to

low humour. Their folk

songs are so comical and

burlesque that one cannot

listen to them without

side-splitting laughter.

The Punch-and-Judy

spirit shines through

everywhere, and the

melodies are mostly

excellent and inimitably

beautiful'.

(One must keep in mind in

reading this account that

the Archbishop of Salzburg

was both a clergyman and a

temporal ruler; hence the

church and court musicians

were one and the same.)

During the same period

that Schubart visited

Salzburg, Charles Burney

published a report sent

from there in November

1772 by an unidentified

writer who (whatever else

he may have been) was

clearly not an admirer

of Mozart's

orchestral music:

'The archbishop and

sovereign of Saltzburg

[sic] is very

magnificent in his support

of music, having usually

near a hundred performers,

vocal and instrumental, in

his service. This prince

is himself a dilettante,

and good performer on the

violin; he has lately been

at great pains to reform

his band, which has been

accused of being more

remarkable for coarseness

and noise, than delicacy

and high-finishing.

Signor Fischietti, author

of several comic operas,

is at present the director

of this band.

“The Mozart family were

all at Saltzburg last

summer; the father has

long been in the service

of the court, and the son

is now one of the band...

I went to his father's

house to hear him and his

sister play duets on the

same harpsichord... and...

if I may judge of the

music which I heard of his

composition, in the

orchestra, he is one

further instance of early

fruit being more

extraordinary

than excellent'.

Mozart's opinion of the

Salzburg orchestra was far

from enthusiastic. He had

heard the great orchestras

of Mannheim, Turin, Milan,

and Naples, and he knew

that the Salzburg

orchestra, although

moderately large for its

time, was too often

second-rate in its

execution. Writing to his

father from Mannheim in

1778, he compared the

fabulous orchestra there

with their own:

'Ah,

if only we too had

clarinets! You cannot

imagine the glorious

effect of a symphony with

flutes, oboes, and

clarinets. I shall have

much that is new to tell

the Archbishop at my first

audience, and perhaps a

few suggestions to make as

well. Ah, how much finer

and better our orchestra

might be, if only the

Archbishop desired it.

Probably the chief reason

why it is not better is

because there are far too

many performances. I

have no objection to the

chamber music, only to the

concerts

on a larger scale'.

The truth about the

quality of the Salzburg

orchestra undoubtedly

lay somewhere between

Schubart's glowing

appraisal and Mozart's

frequent complaints. As

for its strength, the

official roster of court

musicians published in

the Salzburger Hofkalender

für

1775 shows Joseph

Lolli and Dominicus

Fischietti, both

Kapellmeister, Leopold

Mozart, Vizekapellmeister,

Michael Haydn and

Wolfgang Mozart, both Conzertmeister,

as well as 3 organists,

8 violinists, 1 cellist,

3 double bass players, 2

bassoonists, 3 oboists,

and 3 hunting horn

players. Even a casual

examination of this list

suggests that something

is missing, for Mozart's

Salzburg works often

include parts for

flutes, trumpets, and

timpani, as well as

divided viola parts and

an additional horn. It

appears that several of

these 33 musicians

played more than one

instrument, and there

were others who could be

- and were - called upon

to supplement the

orchestra. These

included the town waits,

the trumpet - and

kettle-drum players of

the Archbishop's army,

and various amateur

performers whose

principal posts at court

were non-musical. Thus

the make-up of the

Salzburg orchestra

varied widely from

season to season and

from occasion to

occasion. As we have

reconstituted the

orchestra for these

recordings, it is as it

may have been heard at

festive occasions during

the year: the strings

9-8-4-3-2, and the

necessary woodwind,

brass, kettle drums and

harpsichord, with 3

bassoons doubling the

bass line whenever

obbligato parts for them

are lacking.

The Symphony as a

Genre

After Beethoven, the

symphony was the most

important large-scale

instrumental genre for

the Romantic composers.

Their conception of the

symphony as an extended

work of the utmost

seriousness, intended as

the centrepiece of a

concert, is very far

from what the musicians

of the second half of

the 18th century had in

mind for their

symphonies. This can be

seen by comparing the

large number of

symphonies turned out

then with the handful

written by the major

19th-century

symphonists. It

can also be seen in the

small number and brevity

of passages devoted to

symphonies in the

newspaper accounts,

memoires and

correspondence of the

period. And it can be

seen in the uses to

which 18th-century

symphonies were put.

'Sinfonia' and

'overtura' or

'ouverture' were

synonymous terms and

concepts then. Planelli

writing in 1772 gave a

typically simple Italian

definition: 'All the

symphonies that serve

[operas] as overtures

are cast from the same

die, and are inevitably

made up of a solemn

grouping of an allegro,

a largo, and a dance'.

The French naturalist

and composer Étienne

de la Ville, Comte de

Lacépède, a

decade later began by

elaborating on

essentially the same

definition: 'A symphony

is ordinarily made up of

3 movements: the first

is more noble, more

majestic, more imposing;

the second slower, more

touching, more pathetic

or more charming; and

the third more rapid,

more tumultuous, more

lively, more animated or

more gay, than the other

two'. He then presented

a characteristic French

notion that a good

symphony must be

dramatic and even

programmatic: ‘The first

movement, that which we

call the allegro

of the symphony, should

present, so to speak,

its overture and the

first scenes; in the andante

or the second movement,

the musician should

place the portrayal of

terrible happenings,

dangerous passions, or

charming objects, which

should serve as the

basis for the piece; and

the last movement, to

which we commonly give

the name presto,

should offer the last

effort of these

frightful or touching

passions. The dénouement

should also be shown

here, and one should see

subsequently the

sadness, fright and

consternation that a

fatal catastrophe

inspires, or the joy,

happiness and ecstasy to

which charming and happy

events give birth...'

Then follow several

pages in this vein,

suggesting how the

scenarios of such

programmatic symphonies

might be handled.

From Germany Schubart

embellished the basic

Italian definition in a

different way: 'This

genre of music

originated from the

overtures of musical

dramas, and came finally

to be performed in

private concerts. As a

rule it consists of an

allegro, an andante, and

a presto. However, our

artists are no longer

bound to this form, and

often depart from it

with great effect.

Symphony in the present

fashion is, as it were,

loud preparation for and

vigorous introduction to

hearing a concert'. In

Mozart's case the most

familiar departure from

the 3-movement

format was the insertion

of a minuet and trio

between the andante and

the finale. This is a

characteristic Austrian

development, and Mozart

not infrequently converted

one of his Italian

symphonies to an Austrian

one by the simple

expedient of adding a

minuet and trio.

Mozart wrote his

symphonies as

curtainraisers to plays,

operas, cantatas,

oratorios, and private and

public concerts. He

sometimes also used them

to end concerts, or even

to begin and end each half

of a long concert. Judging

by the number of

symphonies he wrote in

Salzburg (or those that he

wrote for Italy

and then used in

Salzburg), there must have

been a steady demand for

them there. During the

4-year period 1770-73

alone he wrote 28

symphonies. This

outpouring can be

explained at least in part

by the death of the

Archbishop Sigismund

Christoph von

Schrattenbach in December

1771, which meant that a

period of mourning

prohibited theatrical

entertainments during Fasching

(carnival) and that

concerts would have

provided a substitute form

of entertainment. It also

meant that much new music

would have had to be

provided for the

festivities surrounding

the installation in March

of the new archbishop, the

despised Hieronymus

Joseph

Franz de Paula Graf

Colloredo. A further

explanation for the

surprising number of

symphonies during this

period is that Mozart was

officially promoted from

rank-and-file member of

the orchestra to the

status of Konzertmeister

on August 1772. (Was this

perhaps part of the new

archbishop's 'great pains

to reform his band', which

Burney's informant

mentioned?) Mozart's

efforts to prove himself

worthy of the appointment,

and the responsibilities

of the post once assumed,

may well explain in part

his need to write so many

symphonies. These include

- in addition to those

that, because we know of

no specific occasion for

their creation, we

(rightly or wrongly)

consider to have

originated as concert

symphonies - a number of

other concert symphonies

that Mozart fashioned from

works in other genres.

Among the latter were

opera overtures detached

unchanged from their

operas and put into

circulation, opera

overtures provided with

new finales to bring them

up to the customary 3

movements, and groups of

3, 4, or even 5 movements

drawn from orchestral

serenades.

With the arguable

exception of the last few,

Mozart's symphonies were

perhaps intended to be

witty, charming,

brilliant, and even

touching, but undoubtedly

not profound, learned, or

of great significance. The

main attractions at

concerts were not the

symphonies, but the vocal

and instrumental solos and

chamber music that the

symphonies introduced.

Approaching Mozart's

symphonies with this

attitude in mind relieves

them of a romantic

heaviness under which they

have all too often been

crushed. Thus unburdened,

they sparkle with new

lustre.

Performance Practice

The use of 18th-century

instruments with the

proper techniques of

playing them gives to the

Academy of Ancient Music a

clear, vibrant, articulate

sound. Inner voices are

clearly audible without

obscuring the principal melodies.

Rhythmic patterns and

subtle differences in

articulation are more

distinct than can usually

be heard with modern

instruments. The use of

little or no vibrato

serves further to clarify

the texture. At lively

tempos and with this

luminous timbre, the

observance of all of

Mozart's repeats no longer

makes movements seem too

long. A special instance

concerns the da capos of

the minuets, where, an

ancient oral tradition

tells us, the repeats are

always omitted. But, as we

were unable to trace that

tradition as far back as

Mozart's time, we

experimented by including

those repeats as well.

Missing instruments

understood in 18th-century

practice to be required

have been supplied: these

include bassoons playing

the bass-line along with

the cellos and double

basses, kettle drums

whenever trumpets are

present (except in the

'little' G-minor symphony,

K.183,

where chromaticism renders

their use less idiomatic)

and the harpsichord

continuo. No conductor is

needed, as the direction

of the orchestra is

divided in true

18th-century fashion

between the concertmaster

and the continuo player,

who are placed so that

they can see each other

and are visible to the

rest of the orchestra.

Following 18th-century

injunctions to separate

widely the softest and

loudest instruments, the

flutes and trumpets are

placed at opposite sides

of the orchestra. And the

first and second violins

are placed at the left and

right respectively,

making meaningful the

numerous passages Mozart

wants tossed back and

forth between them.

Musical Sources and

Editions

Until recently

performers of Mozart's

symphonies have relied

upon the editions drawn

from the old complete

works, published in the

19th century by the

Leipzig firm of

Breitkopf & Härtel.

During the past quarter

century, however, a new

complete edition of

Mozart's works (NMA)

has been slowly

appearing, published by

Bärenreiter

of Kassel under the

aegis of the Mozarteum

of Salzburg. The NMA

has been used for almost

all the symphonies from

K.128 to K.551. For the

early symphonies not yet

published in the NMA,

editions have been

created especially for

these recordings,

drawing on Mozart's

manuscripts when they

could be seen, and on

18th- and 19th-century

copies in those cases

where the autographs

were unavailable. (14 of

Mozart's symphonies are

among musical

manuscripts formerly in

the Berlin library but

now being held in Poland

and inaccessible to

Western musicologists.)

A Note

Concerning the

Numbering of Mozart's

Symphonies

The first

edition of Ludwig Ritter

von Köchel's

Chronological-Thematic

Catalogue of the

Complete Works of

Wolfgang Amaadé

Mozart was published

in 1862 (=K1).

It

listed all of the

completed works of Mozart

known to Köchel

in what he believed to be

their chronological order,

from number 1 (infant

harpsichord work) to 626

(the Requiem). The second

edition by Paul Graf von

Waldersee in 1905 involved

primarily minor

corrections and

clarifications. A

thoroughgoing revision

came first with Alfred

Einstein's third edition,

published

in 1936 (=K3).

(A reprint of this edition

with a sizeable supplement

of further corrections and

additions was published in

1946 and is sometimes

referred to as K3a.)

Einstein changed the

position of many works in

Köchel's

chronology, threw out as

spurious some works Köchel

had taken to be authentic,

and inserted as authentic

some works Köchel

believed spurious or did

not know about. He also

inserted into the

chronological scheme

incomplete works,

sketches, and works known

to have existed but now

lost. These Köchel

had

placed in an appendix (=Anhang,

abbreviated Anh.)

without chronological

order. Köchel's

original numbers could not

be changed, for they

formed the basis of

cataloguing for thousands

of publishers, libraries,

and reference works.

Therefore, the new numbers

were inserted in

chronological order

between the old ones by

adding lower-case letters.

The so-called fourth and

fifth editions were

nothing more than

unchanged reprints of the

1936 edition, without the

1946 supplement. The sixth

edition, which appeared in

1964 and was edited by

Franz Giegling, Alexander

Weinmann, and Gerd Sievers

(=K6),

continued Einstein's

innovations by adding

numbers with lower-case

letters appended, and a

few with upper-case

letters in instances in

which a work had to be

inserted into the

chronology between two of

Einstein's lowercase

insertions. (A so-called

seventh edition is an

unchanged reprint of the

sixth). Hence, many of

Mozart's works bear two K

numbers, and a few have

three.

Although it was not Köchel's

intention in devising his

catalogue, Mozart's age at

the time of composition of

a work may be calculated

with some degree of

accuracy from the K

number. (This works,

however, only for numbers

over 100). This is done by

dividing the number by 25

and adding 10. Then, if

one keeps in mind that

Mozart was born in 1756,

the year of composition is

also readily approximated.

The old Complete Works of

Mozart published 41

symphonies in 3 volumes

between 1879 and 1882,

numbered 1 to 41 according

to the chronology of K1.

Additional symphonies

appeared in supplementary

volumes and are sometimes

numbered 42 to 50,

even though they are early

works.

Copyright

© 1979 by Neal

Zaslaw

|

|

The

Symphonies of

1772-73

The 11

symphonies presented

here, written between

the time that Mozart was

16 years, 2 months old

and the time that he was

17 years, 8 months, may

be divided into 3

groups: 4 symphonies

(K.130-134)

written in Salzburg

before Mozart's third

trip to Italy, 2 having

connections with both

Salzburg and Italy

(K.135, 141a), and 5

more written after the

return home (K.161a,

161b, 162, 162b, 173dA).

The 11 symphonies may

also be divided into two

groups; Germanic

concert-symphonies with

minuets and repeated

sections in all

movements, each lasting

around 20 to 25 minutes

(K. 130, 132, 133, 134,

161b); and Italianate

overture-symphonies,

without minuets and

mostly without repeats,

each lasting around 8 or

9 minutes. (K. 135,

141a, 161a, 162, 162b,

173dA). The 3 movements

of the Italianate

overture symphonies are

usually linked by

incomplete cadences and

played without pause,

and the third movement

is often based upon a

transformation of the

opening of the first

movement at a faster

tempo.

None of

the symphonies of

1772-73 were printed

during Mozart's

lifetime, although they

are easily the equals of

hundreds of symphonies

which did issue from the

presses. It might appear

that this was the result

of a deliberate policy,

for in 1778 Leopold

Mozart wrote to Wolfgang

that ’... I have not

given any of your

symphonies to be copied,

because I knew in

advance that when you

were older and had more

insight, you would be

glad that no-one had got

hold of them, though at

the time you composed

them you were quite

pleased with them. One

gradually becomes more

and more fastidious'.

Leopold's remarks,

however, may have been

hypocritical, for in

1772 he had written to

the Leipzig publisher J.

G. I. Breitkopf, 'Should

you wish to print any of

my son's

compositions...

you have only to state

what you consider most

suitable. He

could let you have

[various compositions

including] symphonies

for two violins, viola,

two horns, two oboes or

transverse flutes, and

bass'. And again 3 years

later: ‘As I decided

some time ago to have

some of my son's

compositions printed, I

should like you to let

me know as soon as

possible whether you

would like to publish

some of them, that is

symphonies land various

other works'. The

symphonies offered to

Breitkopf must be among

those here recorded. But

Mozart's symphonies were

not to appear in the

Breitkopf catalogue

until 1785-87, and then

only in editions

purchased from other

publishers.

Symphony

in F major, K. 130

Many

commentators, following

Saint-Foix, have

considered this to be

the earliest of Mozart's

truly great symphonies.

Admittedly it is an

excellent work, but does

it really contain better

ideas, better worked

out, than several other

of his symphonies of

this period? It was

written, according to

Mozart's father's

inscription on the

autograph, 'a Salisburgo

nel Maggio 1772'. Mozart

began the first movement

with only a pair of

horns in F in mind. In

the second movement he

had the players switch

to a pair of Bb horns.

By the time he began the

minuet, however, he had

decided to add another

pair of horns, found in

this movement and the

finale, and he then went

back and wrote the

additional horn parts on

blank staves in the

first and second

movements. This change

may have been associated

with the return to

Salzburg from a European

tour of Mozart's friend

(for whom he was later to

write the horn quintet and

horn concertos), the horn

virtuoso Ioseph Leutgeb.

This symphony is the first

of only four symphonies

(K. 130, 132, 183, 318) in

which Mozart used 4 rather

than the customary 2

horns.

The first

movement, in sonata form,

begins quietly without the

usual fanfare. The opening

motive - heard also at the

end of the exposition, in

the development section,

and at the beginning and

end of the recapitulation

- prominently features a

rhythm known in some

circles as the 'Lombardic'

rhythm and in others as

the 'Scotch snap'. It is

also omnipresent in

Hungarian folk music, some

of which Mozart may well

have encountered in his

travels.

Mozart's

first attempt at an

andante movement was

abandoned after only 8

bars. The cancelled

beginning has a more

complex texture than the

completed andante. Could

this be the result of

Leopold looking over

Wolfgang's shoulder and

urging him (as he once did

in a letter) to write

something 'only

short-easy-popular'? In

any case, the completed

andantino grazioso is a

serene, cantabile movement

in 3/8 and in binary form.

The violins are muted, the

cellos and basses

pizzicato; the violas,

however, are without

mutes, confirming that

there were very few of

them in the Salzburg

orchestra. Landon points

out what may or may not be

a coincidence: Joseph

Haydn first wrote 3/8

andante movements in 4

symphonies from the years

1770-72 (Hob. l: 22bis,

39, 42, and 45); could

Mozart have known and

imitated any of these in

his andante?

The minuet

is wittily constructed

around a canon between the

violins (in octaves) and

the bass-line, with the

violas adding a rustic

drone wobbling back and

forth from C to B# (despite

the F-major harmonies).

This leads to a trio

filled with highjinks:

quasi-modal harmonies and

stratospherically high

horn writing. Here was

something special for the

recently returned Leutgeb,

and a bit of Punch and Judy

in the bargain! Lest the

gay exterior of this

movement deceive us about

the craft behind it,

however, it should be

noted that Mozart crossed

out and rewrote a 10-bar

passage in the trio to

achieve the unassuming

perfection of his final

results.

The

energetic finale, molto

allegro, is of a length

and weight to balance the

opening movement, and also

in sonata form, thus

departing from the short

dance-like finale of the

Italians. This buffo

movement is filled with

rushing scales, sudden

changes of dynamics,

tremolos, and other happy

noises much favoured by

the symphonists of the

Mannheim school. Leopold

Mozart called this sort of

music 'nothing but noise',

a judgment that did not

prevent his son

from making

brilliant use of the

style.

Symphony

in Eb major, K. 132

Mozart's

father labelled this

autograph ‘nel Luglio 1772

à

Salisburgo'. The opening

triadic figure with trill

bears a striking

resemblance to the

beginnings of two other

pieces in the same key:

the doubtfully authentic

sinfonia concertante for

winds (K. Anh. C14.01) and

the thoroughly authentic

piano concerto, K. 482.

The notation of the horns

presents a peculiar

problem: Mozart marked the

pairs of horns ‘2 Corni in

E la fa alti, 2 Corni in E

la fa bassi', that is, 2

horns in high Eb, 2 horns

in low Eb. But the

valveless horns that are

known to us from the

period have crooks

enabling them to play in

the following keys only:

low Bb, low C, D, Eb, E,

F, G, Ab, A, high Bb, and

high C. Three possible

solutions present

themselves; (1) a low-Eb

crook combined with the

old Baroque clarino

technique, enabling the

part to be played an

octave higher; (2) an

experimental instrument,

perhaps brought to

Salzburg by Leutgeb, which

has not survived; or (3)

the shortest crook (high

C) and elimination of the

usual tuning bits, thus

inserting the mouthpiece

further up the horn than

is customary. This last

procedure, discovered by

experimentation during

rehearsals for these

recordings to yield an

instrument pitched in high

Eb, was the one used here.

Two

complete slow movements

survive for this symphony

- an andante in 3/8, found

in the normal location

between the first movement

and the minuet, and a

substitute andantino

grazioso in 2/4, written

into the manuscript

following the finale. Mila

finds Mozart's second

attempt superior to the

first, while most other

commentators (and the

writer of these notes)

find precisely the

opposite. Plath has

recently pointed out that

the 3/8 movement is based

at least in part upon

borrowed materials. The

opening melody reproduces

the incipit of a Gregorian

melody for the Credo.

The

significance of this

quotation is unclear, but

we must mention that Joseph

Haydn quoted Gregorian

chant in the slow

movements of 2 of his

symphonies (26, 60). Later

in the movement there

appears a variant of a

popular mediaeval German

Christmas carol, a tune

that Mozart had used once

before in a first version

of his Gallimathias

musicum, K 32. Here

is the beginning of the

carol in the 1599 version

of Erhard Bodenschatz. Is

Mozart trying his hand at

Lacépède's

programme symphony?

The

andantino grazioso,

entirely original as far

as is known, features a

beautiful cantilena shared

between the violins and

the oboes and making an

effective dialogue with

the rest of the orchestra.

The minuet

begins with a lively

canonic exchange between

the first and second

violins. The tune is soon

imitated by the bass

instruments and then heard

in one voice or another

throughout the piece,

including after a

humourously timed pause

just before the return of

the beginning in the

middle of the second

section. The trio (and

that of K 130) has been

called 'daring and

bizarre' by Wyzewa and

Saint-Foix, while Abert

too noted a 'tendency

toward eccentricity'. It

also brings to mind Lacépède's

notion of a programmatic

symphony, for it appears

to be based upon a melody

in the style of a psalm

tone, set in imitation of

the stile antico

of a post-Renaissance

motet. A brief outburst of

ball-room gaiety at the

beginning of the second

section is the only

intrusion of the secular

world into the sanctimony

of the psalmody. (Mozart's

psalm tone is performed

here one on a part,

acknowledging that many

German court orchestras of

the period divided their

rosters into highly paid soloisten

and poorly paid ripienisten.)

Was this Mozart's

commentary on the mixture

of secular and sacred

concerns at the court of

the Prince-Archbishop of

Salzburg? Was this

symphony destined for

sacred rather than secular

use? Could Haydn have once

again pointed the way with

the Gregorian melody in

the trio of his Symphony

45 ('Farewell')? We may

never know the answers to

these intriguing

questions.

The finale

is a substantial piece in

the form of a gavotte

or contredanse en

rondeau. This is as

French as Mozart's music

ever becomes, and filled

with a kind of mock naïveté

of which, one imagines,

those of the French

nobility who enjoyed

playing at shepherd and

shepherdess would have

approved. Mozart, however,

was not fond of most

French music (he

exasperatedly called it

'trash' and 'wretched'),

and wrote of some of his

Salzburg symphonies,

'...most of them are not

in the Parisian taste'.

Symphony

in D major, K. 133

Written in

July

1772, the work opens with

3 tutti chords, after

which a characteristic

rising sequential theme

follows in the strings.

Flourishes in the kettle

drums and trumpets, as

well as the other winds,

inform us that this is a

festive work. A lyrical

section of the exposition

features the 'Lombardic'

rhythm found in several

other syrnphonies of the

period. An exceptionally

well-worked-out

development section

returns to the tonic key

without presenting the

opening theme. That theme

Mozart saves for the end,

where it is heard in the

strings and then, in a

grand apotheosis, is heard

again doubled by the

trumpets.

The

graceful, binary andante

in 2 is scored for strings

(once again violins muted

and the bass instruments

pizzicato) with the

addition of a solitary

'flauto traverso

obligato'. We should not

imagine the poor flautist

sitting disconsolately

during the other 3

movements with nothing to

play. Rather, we should

imagine a player of

another instrument picking

up a flute for this

movement.

The minuet

is typically Austrian,

that is, short, simple,

and fast, in contrast to

Italian minuets which,

Mozart tells us,

'generally have plenty of

notes, are played slowly

and are many bars long'.

The trio once again

provides an opportunity

for Mozart to shake a few

tricks from his sleeve, in

this case syncopations,

suspensions, and other

devices of learned

counterpoint, or precisely

the opposite of the

homophonic texture

normally found in dance

music. The finale is an

enormous 1/8/2 jig in

sonata form that, once

launched, continues

virtually without rest to

its breathless conclusion.

Symphony

in A major, K. 134

Written in

August 1772, this symphony

eschews the customary

march-like 4/4 opening in

favour of one in 3/4. The

orchestra is at its

smallest - strings and

pairs of flutes and horns

(with bassoons and

harpsichord added) - and

Saint-Foix finds the whole

'astonishingly imaginative

and poetic'. The first

movement is as close as

Mozart comes to writing a

monothematic sonata-form

movement. (Haydn was much

fonder than Mozart of

monothematicism, and less

attached to the insertion

of contrasted themes.)

Perhaps the approach to

monothematicism is the

reason that Mozart felt

the need, rather unusually

for him at this period, to

add an 18-bar coda in

which, after a brief

allusion to the principal

theme, a few triadic

flourishes assure even the

most inattentive listener

that the close has been

reached.

The andante

opens with a melody that

Mozart was surely inspired

to write by Gluck's famous

aria for Orpheus, 'Che farò

senza Euridice?'. The

cantabile beginning is

spun out at some length

into a sonata-form

movement of considerable

subtlety. The texture is

especially carefully

thought out, with an

elaborate second violin

part and divided violas.

The minuet

has a Haydnesque

brusqueness about it. A

Punch-and-Judy

tendency again shows in

the trio, with its

virtually melodyless first

strain and in the second

strain antiphonal chords

tossed between the wind

and the violins pizzicato

over a drone in the

violas, arriving at a

peculiarly chromatic

passage to prepare the

return of the opening

'non-melody'.

The finale

begins with a bourrée

which, however, is

subjected to full

development in sonata form

with coda. Despite the

scale on which the

movement is written, the

spirit of the dance

everywhere peers through

the symphonic facade.

Symphony

in D major, K. 135

In 1771

Mozart was granted the scrittura

(commission) to write the

first opera for Milan for

carnival 1773. By October

of 1772 he had received

the libretto of Giovanni

da Gamerra's Lucio

Silla. As he could

not begin composing arias

until he had heard the

principal singers and knew

their capabilities, he

began by thinking about

those numbers that he

could compose in advance:

the recitatives, choruses

and overture. On 24

October he and his father

left for Milan where they

arrived 10 days later. By

14 November Leopold could

report to his wife that

only one of the principal

singers had thus far

arrived in Milan:

'Meanwhile Wolfgang has

got much amusement from

composing the choruses, of

which there are three, and

from altering and partly

rewriting the few

recitatives which he

composed in Salzburg... He

has now written all the

recitatives and the

overture'. That 'overture'

is the 3-movement symphony

recorded here.

Lucio

Silla was a success

and received about 20

performances following its

première

on Boxing Day 1772. Upon

his return to Salzburg,

Mozart was unable to have

his opera performed, as

Salzburg had no opera

house, but he did extract

certain arias to use as

concert pieces, and the

overture circulated as a

concert symphony (as we

leam from its presence in

an early-19th-century

Breitkopf & Härtel

manuscript catalogue). We

have chosen to perform the

symphony as it may have

been heard after Mozart's

return to Salzburg, rather

than with Milanese forces.

The work

opens with a typically

festive, Italianate molto

allegro. The andante is in

a galant vein, avoiding

the more worked-out

part-writing of several of

the andantes written for

Salzburg. This leads to

another molto allegro, a

kind of 3/8 jig in which

running semiquavers

throughout much of the

movement create the

impression of a moto

perpetuo.

Symphony

in D major, K. 141a

(161/ 163)

For the

ceremonies surrounding the

installation of the new

archbishop, Mozart set the

textof a 'Serenata

drammatica' by Metastasio,

Il

sogno di

Scipione, and this

was performed apparently

in early May 1772. The

overture of the work

consisted of an allegro

moderato in alla breve and

an andante in 3/4. Perhaps

anticipating the need to

produce quickly a symphony

while in Milan, Mozart

must have taken those two

movements with him to

Italy, for (according to

the Köchel

catalogue) the finale, a

3/8 presto, was composed

in Milan at the end of

1772. It was the Mozarts'

custom partially to

finance their tours by

giving concerts in each

city they visited.

Undoubtedly something of

the sort was planned for

Milan, even though Leopold

reported that 'It is not

so

easy to

give a public concert here

and it is scarcely any use

attempting to do so

without special patronage,

while even then one is

sometimes swindled out of

one's profits'. If this

symphony was not created

for such a public concert,

then perhaps it was

created for a private one

of the sort described by

Leopold: 'On the evenings

of the 21st, 22nd and 23rd

December great parties

took place in Count

Firmian's house at which

all the nobles were

present. On each day they

went on from five o'clock

in the evening until

eleven o'clock with

continuous vocal and

instrumental music. We

were among those invited

and Wolfgang performed

each evening'.

The 3

movements, linked by

incomplete cadences, are

played without break, and

the finale even begins on

a dominant rather than

tonic chord. Tagliavini

has noted a striking

resemblance between the

subsidiary theme of the

first movement and that of

J.

C. Bach's overture to the

opera Alessandro

nell'Indie (Naples,

1762).

Symphony

in Eb major, K. 161a

(184)

Every

commentator has remarked

on the dramatic character

of this work, which is

dated Salzburg, 30 March

1773. Saint-Foix, for

instance, in his

characteristically

extravagant diction,

states, 'The violence of

the first movement

followed by the infinite

despair of the andante (in

the minor), and the ardent

and joyous rhythms of the

finale mark this symphony

as something quite apart;

romantic exaltation here

reaches its climax...' The

work seems filled with

familiar ideas. The

intense opening gesture of

the molto presto later

served Mozart as a model

for the more relaxed openings

of two other Eb pieces:

the sinfonia concertante,

K. 364, and the wind

serenade, K. 375. The

subsidiary theme of the

same movement bears a

resemblance to a theme

heard in the first

movement of Haydn's

Symphony 52. The poignant

C-minor andante is filled

with appogiaturas and

other effects borrowed

from tragic Italian arias.

The theme of the jig-like

finale is remarkably like

that of the rondo of

Mozart's horn concerto, K.

495, also in Eb.

Throughout the 3

movements, the concertante

writing for winds is

especially well handled.

Although we

do not know why this

exceptionally serious

symphony was written, we

do know that in the 1780s

it was used (apparently

with Mozart's consent) by

the travelling theatrical

troupe of his acquaintance

Johann

Böhm

as the overture to Lanassa

by the Berlin playwright

Karl Martin Plümicke.

This play - a German

adaptation of

Antoine-Marin Lemierre's La

Veuve du Malabar

about a Hindu widow who,

unable to resign herself

to her husband's death,

flings herself onto a

funeral pyre - was also

decked out with Mozart's

incidental music for Thamos,

King of Egypt, K.

345, to which new texts

had been set. This is

undoubtedly why it is

sometimes stated (probably

erroneously) that the

present symphony was

intended as an overture

for Thamos itself.

Symphony

in G major, K. 161b

(199)

Dated 10 or

16 April 1773 (the date is

partially illegible), the

symphony opens with a 3/4

allegro in a small-scale

but perfectly proportioned

sonata-form movement

filled with high spirits.

The serene andante, with

its parallel sixths and

thirds and gracefully

flowing triplets, has only

a touch of chromaticism

occasioned by

augmented-6th chords

toward the end of each

strain to suggest that the

world might contain any

darkness. The finale

begins with some

notentirely-convincing

counterpoint, which rubs

shoulders uneasily with

more galant notions. The

subject of the finale's

fugato (G-C-F#-G) is drawn

from the opening theme of

the first movement.

(Saint-Foix describes the

opening as 'a sort of

fugato that soon takes on

a waltz rhythm'.) Mozart

himself later commented

wryly on this sort of

writing in the finale of

his Musical Joke,

K. 522. It must be

admitted that the

short-windedness of the

opening is somewhat

redeemed by the more

extended version of the

same material that Mozart

offers us at the

recapitulation, where it

serves as both main theme

and retransition. But

counterpoint aside, the

movement jogs as nice a

jig as could be wanted

circa 1773 to bring a

symphony to a happy

conclusion.

Symphony

in C major, K. 162

The date at

the beginning of this

symphony has been defaced

and cannot be confidently

deciphered. The date '19

or 29 April 1773' in the Köchel

catalogue is therefore

somewhat speculative,

although the work clearly

dates from this period.

The opening

gestures of the first

movement in common time

establish the festive

character of the entire

movement. When the brief

development section leads

back to C major at the

recapitulation, the first

12 bars are missing. These

ideas Mozart saves for the

end, where they

serve as an effective

closing section. This is

not the last we hear of

these ideas, however, for,

transformed into 6/8, they

also open the finale,

which is again treated in

a highly concise sonata

form. The intervening

andantino grazioso,

featuring obbligato

writing for oboes and

horns, is reminiscent of

certain movements in

Mozart's orchestral

serenades of this period.

Symphony

in D major, K. 162b

(181)

Dated

Salzburg, 19 May 1773, the

work opens with a flourish

reminiscent of the opening

of the C-major symphony,

K. 162. The movement is an

essay in orchestral

'noises' used to form a

coherent and satisfying

whole. That is, there are

few memorable melodies,

but rather a succession of

instrumental devices,

including repeated notes,

fanfares, arpeggios,

sudden fortes and pianos,

scales, syncopations,

dotted rhythms, etc.

Descriptions and

explanations of musical

form tend to fall back on

linguistic analogies. In

this case, however, such

an analogy would lead us

into the absurd position

of having to imagine

meaningful prose composed

entirely of articles,

conjunctions and

prepositions! Responding

to this, Schultz refers to

the movement as 'purely

decorative'. Schultz's

reaction, Leopold Mozart's

'nothing but noise', the

failure of the linguistic

analogy, and Lacépède's

need for programmes in

symphonies all point to

the same phenomenon: an

inability of aesthetic

theory to deal with an art

of abstract sounds

unsupported by verbal

ideas. (A parallel may be

drawn with the

difficulties surrounding

the acceptance of non-representational

painting in the 20th

century.)

The second

movement, linked to the

first, in some sense

atones for the lack of

beautiful melody in the

allegro by presenting a

moving oboe solo in the

style of a siciliano. This

leads straight into a

cheerful rondo in 2/4 in

the style of a contradance

or march, to which

Saint-Foix correctly

applies the 18th-century

appellation 'quick step'.

Symphony

in Bb

major, K. 173dA (182)

Dated

Salzburg, 3 October 1773,

this work was apparently

still thought highly of by

Mozart in the final decade

of his life. This emerges

from a letter he wrote in

1783 from Vienna to his

father in Salzburg, asking

to be sent this work

(along with others) for

use in concerts in Vienna.

The opening movement is

nearly as full of

orchestral 'noises' as

that of the D-major

symphony, K. 162b,

although a few themes of

note emerge including one

in which the 'Lombardic'

rhythm features

prominently. The andantino

grazioso is of sharply

contrasted timbre, due to

the muted violins, the

change of key to Eb, and

the substitution of a pair

of flutes for the oboes.

This movement is a simple

cantilena in AABA form.

The lively, jig-like

finale which concludes

this Dionesian work is

pure opera buffa from

start to finish.

Copyright

© 1979 by Neal Zaslaw

|

|

|

|

|