|

|

3 LP's

- D168D3 - (p) 1981

|

|

| 2 CD's -

417 518-2 - (c) 1986 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| The Symphonies

- Vol. 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

53' 49" |

|

| Symphony in C

Major, K. 35 |

4' 43" |

|

|

| -

[Sinfonia: Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 38 |

2' 45" |

|

|

| -

[Intrada: Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 100 / K. 62a |

17' 42" |

|

|

| -

[Serenata: Allegro · Menuetto &

Trio · Andante · Menuetto & Trio

· Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 9 in C Major, K. 73 |

11' 53" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante · Menuetto &

Trio · Allegro molto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Minor, K. 118 / K. 74c |

3' 48" |

|

|

| -

[Overture: Allegro-Andante-Presto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 42 in F Major, K. 75 |

12' 58" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Menuetto & Trio ·

Andantino · Allegro] |

|

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

38' 11" |

|

| Symphony

No. 12 in G Major, K. 110 / K. 75b |

16' 30" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

(Andante) · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 14 in A Major, K. 114 |

21' 41" |

|

|

| - [Allegro

moderato · Andante · Menuetto

& Trio · Molto allegro · Anhang:

Menuet K. 61g I] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

46' 04" |

|

| Symphony

No. 15 in G Major, K. 124 |

15' 28" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Presto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 16 in C Major, K. 128 |

13'

52"

|

|

|

| - [Allegro

maestoso · Andante grazioso ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 17 in C Major, K. 129 |

16' 44" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap Schröder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

|

|

| Violins |

Catherine

Mackintosh (Rowland Ross 1978

[Amati]) - Simon Standage

(Rogeri, Brescia 1699) - Monica

Huggett (Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Elizabeth Wilcock

(Grancino, Cremona 1652) - Roy

Goodman

(Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - David Woodcock (Anon. circa

1775) - Joan

Brickley

(Mittewald,

circa 1780) -

Alison Bury

(Anon.

England, circa

1730) - Judith

Falkus

(Eberle,

Prague 1733) -

Christopher

Hirons

(Duke, circa

1775) - John

Holloway

(Sebastian

Kloz 1750) - Polly

Waterfield

( Rowland Ross

1979 [Amati])

- Micaela

Comberti

(Anon. England

circa 1740) -

Miles

Golding

(Anon.

Austria, circa

1780) - Kay

Usher

(Anon.

England, circa

1750) - Julie Miller (Anon. France,

circa 1745) -

Susan

Carpenter-Jacobs

(Franco Giraud 1978

[Amati]) - Robin Stowell (David

Hopf, circa

1780) - Richard

Walz

(David Rubio

1977

[Stradivarius])

- Judith Garside (Anon.

France, circa

1730) - Rachel

Isserlis

(John Johnson

1759) - Robert

Hope Simpson

(Samuel

Collier, circa

1740) - Catherine

Weiss

(Rowland Ross

1977

[Stradivarius])

- Jennifer

Helsham

(Alan Bevitt

1979

[Stradivarius])

- Jane

Debenham

(Anon. German,

18th century)

- Roy

Howat

(Henry

Rawlins,

London Bridge

1775) - Christel

Wiehe

(John Johnson,

London 1759) -

Roy Mowatt

(Rowland Ross

1979

[Stradivarius])

- Roderick

Skeaping

(Rowland Ross

1976 [Amati])

- Eleanor

Sloan

(German(?),

circa 1790) -

June Baines

(Nicholas

Amati 1681) -

Stuart

Deeks

(Saxon, circa

1770)

|

|

|

|

|

| Violas |

Jan Schlapp

(Joseph Hill 1770) - Trevor Jones

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Katherine

Hart (Charles and Samuel Thompson

1750) - Colin Kitching (Rowland Ross

1978 [Stradivarius]) - Nicola Cleminson

(McDonnel, Ireland, circa 1760) - Philip

Wilby (Carrass Topham 1974 [Gasparo da

Salo]) - Annette Isserlis (Ian

Clarke 1978 [Guarnieri]) - Simon

Rowland-Jones (Anon. England, circa

1810) - Judith Garside (Hill School,

England 1766) |

|

|

|

|

| Violoncellos

|

Anthony Pleeth

(David Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Richard

Webb (David Rubio 1975 [Januarius

Gagliano]) - Mark Cuadle (Anon.

England, circa 1700) - Juliet Lehwalder

(Jacob Haynes 1745) |

|

|

|

|

| Double

Basses |

Barry

Guy (The Tarisio, Gasparo da

Salo 1560) - Peter McCarthy

(David Techler, circa 1725) - Keith

Marjoram (Anon., Italy circa

1560) |

|

|

|

|

Flutes

|

Stephen

Preston (Anon. France, circa

1790) - Nicholas McGegan

(George Astor, circa 1790) - Lisa

Beznosiuk (Goulding, London,

circa 1805) - Guy Williams

(Monzani, circa 1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Oboes |

Stanley

King (Rudolf Tutz 1978

[Grundmann]) - Clare Shanks

(W. Milhouse, circa 1760) - Sophia

McKenna (W. Milhouse, circa

1760) - David Reichenberg

(Harry Vas Dias 1978 [Grassi]) |

|

|

|

|

Bassoons

|

Jeremy

Ward (Porthaus, Paris, circa

1780) - Felix Warnock

(Savary jeune 1820) - Alastair

Mitchell (W. Milhouse, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Horns |

William

Prince (Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Keith Maries (Anon.

Germany (?) circa 1785) - Christian

Rutherford (Kelhermann, Paris

1810) - Roderick Shaw

(Raoux, circa 1830) - John

Humphries (Halari, 1825) - Patrick

Garvey (Leopold Uhlmann, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Trumpets |

Michael

Laird (Laird 1977, German) - Iaan

Wilson (Laird 1977, German) |

|

|

|

|

| Timpani |

David

Corkhill (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1810) - Charles Fullbrook

(Hawkes & Son, circa 1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Harpsichord |

Christopher

Hogwood, Nicholas McGegan, David

Roblou (Thomas Culliford,

London 1782) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.

Jude-On-The-Hill, London (United

Kingdom):

- dicembre 1979 (K. 35, 38, 100,

73, 118, 75, 110, 114)

St. Paul's New Southgate, London

(United Kingdom):

- settembre 1978 (K. 128, 129)

- giugno 1979 (K.124)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Peter

Wadland & Morten Winding /

John Dunkerley & Simon Eadon |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - D168D3 (3 LP's) - durata

53' 49" | 38' 11" | 46' 04" - (p)

1981 - Analogico

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 417 518-2 (2 CD's) - durata

70' 31" | 67' 37" - (c) 1986 - ADD |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

and the symphonic

traditions of his

time by Neal

Zaslaw

Salzburg

and its Orchestra

In the year 1757 there

appeared in a Berlin music

magazine an anonymous

‘Report on the Present

State of the Musical

Establishment at the Court

of His Serene Highness the

Archbishop of Salzburg’.

This report lists by name

and function those serving

the archbishop in musical

capacities, with

biographies of the more

important personages and

brief notes on others who

had attained special

distinction. It begins

with the Kapellmeister Johann

Ernst Eberlin (1702-62),

the Vice-Kapellmeister

Giuseppe Francesco Lolli

(1701-78), and the three

court composers: Caspar

Cristelli (dates unknown),

Leopold Mozart (1719-87)

and Ferdinand Siedl (dates

unknown). Concerning

Leopold Mozart we read:

'Herr Leopold Mozart from

the Imperial City of

Augsburg. First violinist

and leader of the

orchestra. He composes

both church and chamber

music. He was born on the

14th of November, 1719,

and soon after completing

his studies in philosophy

and law entered the

princely service in the

year 1743. He has made

himself known in every

branch of composition,

without, however, issuing

anything in print except

for 6 Sonatas a 3 that he

himself engraved in the

year 1740 (principally in

order to gain experience

in the art of engraving).

In July

1756 he published his Violinschule.

Among the compositions by

Herr Mozart which have

become known in

manuscript, numerous

contrapuntal and church

pieces are especially

noteworthy; moreover a

large number of

symphonies, some only a 4,

but some with all the

generally current

instruments; likewise more

than thirty grand

serenades, in which are

introduced solos for

various instruments. Apart

from these he has composed

many Concertos, especially

for transverse flute,

oboe, bassoon, horn,

trumpet, etc., countless

trios and divertimentos

for divers instruments;

also twelve oratorios and

a host of theatre pieces,

even mime plays, and

especially music for

certain special occasions,

such as a military piece

with trumpets,

kettledrums, side drums

and fifes, together with

the ordinary instruments;

a Turkish piece; a piece

with a steel xylophone;

and music for a

sleigh-ride with five

sleigh-bells; not to

mention marches, so-called

notturnos, many hundreds

of minuets, opera dances

and suchlike smaller

pieces...

The

three court composers play

their instruments in the

church as well as in the

chamber, and, in rotation

with the Kapellmeister,

have each the direction of

the Court Music for a week

at a time. All the musical

arrangements depend solely

upon whoever is in charge

each week, as he, at his

pleasure, can perform his

own or other persons'

pieces'.

This report was in fact

written by Leopold, who

gives himself away by

immodestly making his own

biography more than twice

as long as (and more

personal than) any of the

others. His anonymity

permitted him this

self-indulgence, as well

as the possibility of

criticising one of his

violinist colleagues for

preferring to play

technically difficult

pieces while possessing a

weak tone. At the time of

this report, Leopold's

prospects must have seemed

bright indeed: he was well

thought of at the Salzburg

Court and could reasonably

hope for eventual

promotion to

Kapellmeister. His Violin

Method was already

receiving favourable

critical notice. His

devoted wife, after three

tragic infant deaths, had

presented him with two

healthy children, Maria

Anna Walburga Ignatia

(’Nannerl’), soon to turn

six, and Joannes

Chrysostomus Wolfgangus

Theophilus, just turned

one. But Leopold's old age

was to be a bitter one:

for his wife died on a

futile journey to find a

post for Wolfgang, his son

never achieved a suitable

post and married (in

Leopold's eyes) beneath

his station, and he

himself never advanced

beyond the rank of

Vice-Kapellmeister, a fate

that he brought down on

his own head by virtually

abandoning his own career

in order to promote that

of his extraordinary son.

Like Leopold's hopes, the

Salzburg orchestra

steadily declined, not so

much in size as in

discipline and morale. By

the late 1770s, sloppy

playing, slovenly dress,

absenteeism and

drunkenness had become

frequent problems. At the

beginning of Wolfgang’s

musical consciousness,

however, the Salzburg

orchestra was well run and

indeed large for its time.

Counting apprentices and

choir boys, Leopold's

report chronicled some 46

instrumentalists and 56

singers, leaving aside an

organ builder, a

string-instrument maker,

three organ blowers, and

five vacant positions. At

first examination the

string section would

appear to have consisted

of only 16 players

(5-5-2-2-2). This is

deceptive, however,

because many of the

woodwind players also

played string instruments

and, as Leopold added at

the end of his report, 'There

is not a trumpeter or

kettledrummer in the

princely service who does

not play the violin well,

who then all appear when

large-scale music is

performed at Court and

play second violin or

viola, which it is in the

purview of whoever is in

charge of the weekly

direction to order'.

The court musicians were

also often supplemented by

various amateur

performers. Thus a string

section of 10-10-4-6-3 or

larger could be assembled

without great difficulty.

For the ordinary daily

rounds of music-making,

however, a system of

rotation provided the

necessary players without

everyone having to play on

any given day.

We have reconstituted the

orchestra for these

recordings as it may have

been heard at festive

occasions during the year:

the strings 9-8-4-3-2, and

the necessary woodwind,

brass, kettledrums and

harpsichord, with three

bassoons doubling the bass

line whenever obbligato

parts for them are

lacking.

The Symphony as a Genre

By the time the

ten-year-old Mozart came

to write the earliest

symphonies in this box -

his first written in and

for Salzburg, as far as we

know - he had visited many

of the major musical

centres of Germany,

Austria, France, England

and the Low Countries. In

those places he heard the

latest symphonies, and

wrote a few of his own in

imitation of what he

heard. But much of that

which the child symphonist

needed to learn could be

learned nearer to home,

for Salzburg had its own

symphonists (Cristelli,

Siedl, Anton Adlgasser

(1729-77), Leopold Mozart

himself, and especially

Michael Haydn (1737-1806),

who joined the Salzburg

establishment in 1762),

and by the 1760s,

German-speaking composers

were beginning to dominate

symphonic production in

all of Western Europe.

This is evident from the

large number of German

symphonies published in

Paris, Amsterdam and

London, as well as from

such remarks as these in a

French essay of 1770, 'Some

Reflexions upon Modern

Music':

'While the French and the

Italians were disputing

which of them possessed

music, the Germans learned

it, going to Italy for

that purpose. Before the

Germans had the advantage

of having any great men

themselves, they had that

of sensing the merit of

their neighbours. The

German artists filled the

public conservatories of

Naples; people of quality

sent their sons to the

most famous masters...

They had all the raw

materials required of

great musicians; they

lacked only the discipline

to organize those

materials, and they had no

trouble acquiring that...

The Italians have for a

long time divided their

music into two genres:

church music and theatre

music. In the first they

bring together all the

forces of harmony, the

most striking chord

progressions - in a word,

the effect; and that is

what they seek to combine

with melody, which they

never abandon. Here it is

that one finds such well

worked-out double and

triple fugues, those

pieces for two choirs or

for double orchestra - in

fact, the most elaborate

things that the art of

music is capable of

producing. The theatrical

genre rejects all of these

tours de force

absolutely. Here the

Italians employ nothing

learned; everything

devolves upon the

melody...

It is quite simple on this

basis to teach composition

to young people: one makes

them work only on church

music; one shows them

matters of labour before

showing them matters of

taste. Upon leaving the

schools, the Italian

pupils remain in their own

country. Those who intend

their talents to be

employed in the theatre

learn its procedures and

genres: in frequent

examples they see what

they must remember and

what they must forget. The

Germans, on the contrary,

return to their country.

They have carefully

preserved their prodigious

accumulation of [musical]

science. They have tested

the very fortunate use of

wind instruments of which

their nation makes much use,

and they have known how to

draw the most from them.

If they wished to work for

the theatre, they had only

scores for models.

Score-reading is not as

seductive as live

theatre... They have

realized that all

expression does not suit

vocal melody; that there

are a thousand nuances

which the orchestra is

much more fit to render

[than the voice].

They have tried, they have

succeeded, and have raised

themselves far above their

masters, who now rush to

imitate them. Here is what

formed the likes of Hasse,

[J.C.]

Bach, Gluck, and

Holzbauer. Let the

Italians bring out

symphonies of their best

masters, and let them

compare them with those of

[J.]

Stamitz, [C.J.]

Toeschi, and Van Malder!

Is not Monsieur Gossec

himself - the only one

among us French who can

walk alongside these great

men in the symphonic genre

- a student of the German

school?'

Our notions of the

symphony, inherited from

the 19th century, are

quite different from those

of the 18th century. After

Beethoven, the symphony

was the most important

large-scale instrumental

genre for the Romantic

composers. Their

conception of the symphony

as an extended work of the

utmost seriousness,

intended as the

centre-piece of a concert,

is very far from what the

musicians of the second

half of the 18th-century

had in mind for their

symphonies. This can be

seen by comparing the

large number of symphonies

turned out then with the

handful written by the

major 19th-century

symphonists. It can also

be seen in the small

number and brevity of

passages devoted to

symphonies in the

newspaper accounts,

memoires and

correspondence of the

period. And it can be seen

in the uses to which 18th-century

symphonies were put.

With the arguable

exception of his last few,

Mozart’s symphonies were

perhaps intended to be

witty, charming,

brilliant, and even

touching, but undoubtedly

not profound, learned, or

of great significance. The

main attractions at

concerts were not the

symphonies, but the vocal

and instrumental solos and

chamber music that the

symphonies introduced.

Approaching Mozart’s

symphonies with this

attitude in mind relieves

them of a romantic

heaviness under which they

have all too often been

crushed. Thus unburdened,

they sparkle with new

lustre.

Performance Practice

The use of

18th-century instruments

with the proper techniques

of playing them gives to

the Academy of Ancient

Music a clear, vibrant

articulate sound. Inner

voices are clearly audible

without obscuring the

principal melodies.

Rhythmic patterns and

subtle differences in

articulation are more

distinct than can usually

be heard with modern

instruments. The use of

little or no vibrato

serves further to clarify

the texture. At lively

tempos and with this

luminous timbre, the

observance of all of

Mozart’s repeats no longer

makes movements seem too

long. A special instance

concerns the da capos of

the minuets, where an

ancient oral tradition

tells us, the repeats are

always omitted. But, as we

were unable to trace that

tradition as far back as

Mozart’s time, we

experimented by including

those repeats as well.

Missing instruments

understood in 18th-century

practice to be required

have been supplied: these

include bassoons playing

the bass-line along with

the cellos and double

basses, kettledrums

whenever trumpets are

present, and the

harpsichord continuo. No

conductor is needed, as

the direction of the

orchestra is divided in

true 18th-century fashion

between the concertmaster

and the continuo player,

who are placed so that

they can see each other

and are visible to the

rest of the orchestra.

Following 18th-century

injunctions to separate

widely the softest and

loudest instruments, the

flutes and trumpets are

placed at opposite sides

of the orchestra. And the

first and second violins

are placed at the left and

right respectively, making

meaningful the numerous

passages Mozart wants

tossed back and forth

between them.

Musical Sources and

Editions

Until recently performers

of Mozart’s symphonies

have relied solely upon

editions drawn from the

old Complete Works,

published in the 19th

century by the Leipzig

firm of Breitkopf & Härtel.

During the past three

decades, however, a new

complete edition of

Mozart’s works (NMA)

has been appearing,

published by Bärenreiter

of Kassel under the aegis

of

the Mozarteum of Salzburg.

The NMA has been

used almost all the

symphonies from K. 128 to

K. 551. For the early

symphonies not yet

published in the NMA,

editions have been created

especially for these

recordings, drawing on

Mozart's manuscripts, when

they could be seen, and on

18th- and 19th-century

copies in those cases

where the autographs were

unavailable.

The Symphonies of

1766-72

The eleven symphonies

presented here, written

between the ages of 10

years 2 months and 16

years 4 months, may be

divided into four

categories: three

overtures intended in the

first instance for vocal

works but later used as

independent concert pieces

(K. 35, 38, 74c); five

Germanic concert

symphonies with minuets

and (usually but not

always) with repeated

sections in all movements,

(K. 73, 75, 75b, 114,

124); two Italianate

overture-symphonies,

without minuets, (K. 128,

129); and one

five-movement symphony

drawn from an

eight-movement serenade

(K. 62a). None of these

works were published in

the 18th century.

Chronologically the

production of these works

falls into four periods of

residence in Salzburg, in

between those trips on

which Leopold took

Wolfgang both to educate

him and to exploit his

status as child prodigy.

This may be represented as

follows:

Journey

to Mannheim - Paris -

London - The Hague

Stay in Salzburg, 29 or 30

November 1766-11 September

1767: K. 35, 38

Journey

to Vienna

Stay in Salzburg, 5 January

1769-13 December 1769: K.

62a, 73

Journey

to Italy

Stay in Salzburg, 28 March

1771-13 August 1771: K.

74c, 75, 75b

Journey

to Italy

Stay in Salzburg, 15

December 1771-24 October

1772: K. 114, 124, 128,

129 [as well as K. 130,

132, 133, 134 found in Box

3]

Joumey

to Italy.

Added to the third of

these four Salzburg stays

should perhaps also be the

Symphony in Bb, K. Anh.

C11.03 [Anh. 216/74g],

which, however, will be

dealt with in Box 7 of

these recordings.

Furthermore, three lost

symphonies known ,only by

their incipits (K. 66c

[Anh. 215], 66d [Anh.

217], 66e [Anh. 218]) may

belong to the second or

third of these periods.

In February 1772, Leopold

Mozart wrote to the

Leipzig publisher

Breitkopf offering him

various of his son's

works, including

symphonies. It is usually

stated that, as far as

symphonies are concerned,

nothing came of Leopold's

offer, because the Leipzig

publisher never printed

any of Wolfgang's

symphonies during the

composer’s lifetime. This

constitutes a serious

misunderstanding.

Breitkopf printed music

only by means of moveable

type, a method suited

primarily to keyboard

music, songs, and other

items in short score. For

the 'publication' of sets

of parts, the customary

methods were either

engraving or hand copying,

and in fact the bulk of

Breitkopf's business

consisted of manuscript

copies. This therefore

must have been what

Leopold had in mind, and

in the old Breitkopf

archives there was indeed

found a collection of

parts for ten of

Wolfgang's symphonies from

the period 1767-73.

Some six years later

Leopold wrote to Wolfgang,

rather unfairly and in the

light of his own dealings

with Breitkopf, I think,

hypocritically:

'It is better that

whatever does you no

honour, should not be

given to the public. That

is the reason why I have

not given any of your

symphonies to be copied,

because I suspect that

when you are older and

have more insight, you

will be glad that no one

has got hold of them,

though at the time you

composed them you were

quite pleased with them.

One gradually becomes more

and more fastidious'.

A Note Concerning the

Numbering of Mozart's

Symphonies

The first

edition of Ludwig Ritter

von Köchel's

Chronological-Thematic

Catalogue of the

Complete Works of

Wolfgang Amaadé

Mozart was published

in 1862 (=K1).

It

listed all of the

completed works of Mozart

known to Köchel

in what he believed to be

their chronological order,

from number 1 (infant

harpsichord work) to 626

(the Requiem). The second

edition by Paul Graf von

Waldersee in 1905 involved

primarily minor

corrections and

clarifications. A

thoroughgoing revision

came first with Alfred

Einstein's third edition,

published

in 1936 (=K3).

(A reprint of this edition

with a sizeable supplement

of further corrections and

additions was published in

1946 and is sometimes

referred to as K3a.)

Einstein changed the

position of many works in

Köchel's

chronology, threw out as

spurious some works Köchel

had taken to be authentic,

and inserted as authentic

some works Köchel

believed spurious or did

not know about. He also

inserted into the

chronological scheme

incomplete works,

sketches, and works known

to have existed but now

lost. These Köchel

had placed in an appendix

(=Anhang,

abbreviated Anh.)

without chronological

order. Köchel's

original numbers could not

be changed, for they

formed the basis of

cataloguing for thousands

of publishers, libraries,

and reference works.

Therefore, the new numbers

were inserted in

chronological order

between the old ones by

adding lower-case letters.

The so-called fourth and

fifth editions were

nothing more than

unchanged reprints of the

1936 edition, without the

1946 supplement. The sixth

edition, which appeared in

1964 and was edited by

Franz Giegling, Alexander

Weinmann, and Gerd Sievers

(=K6),

continued Einstein's

innovations by adding

numbers with lower-case

letters appended, and a

few with upper-case

letters in instances in

which a work had to be

inserted into the

chronology between two of

Einstein's lowercase

insertions. (A so-called

seventh edition is an

unchanged reprint of the

sixth). Hence, many of

Mozart's works bear two K

numbers, and a few have

three.

Although it was not Köchel's

intention in devising his

catalogue, Mozart's age at

the time of composition of

a work may be calculated

with some degree of

accuracy from the K

number. (This works,

however, only for numbers

over 100). This is done by

dividing the number by 25

and adding 10. Then, if

one keeps in mind that

Mozart was born in 1756,

the year of composition is

also readily approximated.

The old Complete Works of

Mozart published 41

symphonies in 3 volumes

between 1879 and 1882,

numbered 1 to 41 according

to the chronology of K1.

Additional symphonies

appeared in supplementary

volumes and are sometimes

numbered 42 to 50,

even though they are early

works.

©

1980

Neal Zaslaw

Bibiography

- Abert,

Hermann: W. A.

Mozart, 7th

ed. (Leipzig,

1955-66)

- Anderson,

Emily: The Letters

of Mozart & His

Family (London,

1966)

- Della

Croce, Luigi: Le

75 sinfonie de

Mozart (Turin,

1977)

- Deutsch,

Otto Erich:

Mozart, A

Documentary

Biography, 2nd

ed. (London, 1966)

- Eibl,

Joseph Heinze, et al.:

Mozart: Briefe und

Aufzeichnungen

(Kassel, 1962-75)

- Framery,

Nicolas Etienne:

'Quelques réflexions

sur la musique

moderne', Journal

de musique

historique,

théorique, et

pratique (May

1770)

- Hausswald,

Günter:

Mozarts

Serenaden. Ein

Beitrag zur

Stilkritik des

18. Jahrhunderts.

(Leipzig, 1951)

- Larsen,

Jens Peter: 'The

Symphonies', The

Mozart

Companion

(London, 1956)

- Larsen,

Jens

Peter: 'A Challenge to

Musicology: the

Viennese Classical

School', Current

Musicology

(1969), ix

- Mahling,

Christoph-Hellmut:

'Mozart und die

Orchesterpraxis seiner

Zeit', Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1967)

- Mila,

Massimo: Le

Sinfonie de Mozart

(Turin, 1967)

- Mozart,

Leopold: 'Nachricht

von

dem gegenwärtigen

Zustande der Musik

sr. Hochfürstl.

Gnaden des

Erzbischoffs zu

Salzburg im Jahr

1757', Historisch-kritische

Beyträge

zur Aufnahme der

Musik

(1757), iii

- Saint-Foix,

Georges de: Les

Symphonies de Mozart

(Paris, 1932)

- Schneider,

Otto, and Anton

Algatzy: Mozart-Handbuch

(Vienna, 1962)

- Schultz,

Detlef: Mozarts Jugendsinfonien

(Leipzig, 1900)

- Sulzer,

Johann

Georg: Allgemeine

Theorie der schönen

Künste

(Berlin, 1771-74)

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'The Compleat

Orchestral Musician',

Early Music

(1979), vii/1

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'Toward the

Revival of the

Classical Orchestra',

Proceedings of the

Royal Musical

Association

(1976-77), ciii

|

|

Symphony in

C major, K. 35

In late 1766 and early

1767 Mozart set Part 1

of a Lenten oratorio, Die

Schuldigkeit des

ersten und fürnehmsten

Gebots ('The

Obligation of the First

and Foremost

Commandment'). The

second and third parts

of this oratorio - the

text of which is by the

Salzburg Burgomaster

Ignaz Anton Weiser

(1701-85) - were set by

Michael Haydn and Anton

Adlgasser

respectively. Mozart’s

portion received its

première in

the Knights' Hall of the

archepiscopal palace on

12 March, with a second

performance on 2 April.

Haydn's portion was

performed on 19 March,

and Adlgasser's probably

on 26 March. According

to the libretto for Part

1, 'The action takes

place in a pleasant

landscape with a garden

and a small wood', and

there are stage

directions throughout.

Nonetheless, it is

likely that the 'theatre

of the mind' was

intended rather than the

stage. The protagonists

of this frigid allegory

are: The Spirit of

Christianity, The World

Spirit, Divine Mercy,

and Divine Justice.

In Part 2 'A Lukewarm

and Afterwards Ardent

Christian' is added to

the cast of characters.

Mozart’s setting

consists of seven arias

and a concluding

terzetto, interspersed

with recitatives. This

is prefaced by an

orchestral movement

headed 'Sinfonia.

Allegro', which is the

symphony presented here.

From its character this

energetic commontime

allegro, with its

Italianate opening

melody in sixths

accompanied by a

repeated-note bass line,

could just as well have

served to launch an

opera. Carl Ferdinand

Pohl, who in 1864

rediscovered the lost

autograph manuscript of

Die Schuldigkeit

in the Royal Library at

Windsor Castle (where it

is still located),

characterised the

'Sinfonia' as 'simple

and natural in structure'.

It is in binary form,

with both halves

repeated. The opening

section rapidly comes to

rest on the dominant,

and a contrasting 'sigh'

motive is heard several

times. (This motive is

featured prominently in

the second half of the

movement, in thirds,

sixths, and octaves;

upside down and

rightside up.) A brief

return of the opening

idea leads to a sonorous

closing section, with

tremolo in the violins

and the melodic interest

transferred to the bass.

The second half begins

as did the first but in

the dominant key. No new

ideas are introduced;

rather the ideas of the

first half are skilfully

manipulated through

several keys and changes

of orchestration, before

the return of the home

key and the opening idea

a mere fifteen bars from

the end. The entire

small-scale movement is

well wrought and in the

period's most modern,

galant vein.

Symphony in D major,

K. 38

In Leopold Mozart’s

catalogue of his son’s

childhood works, one

reads the entry: 'Apollo

and Hyacinth,

music to a Latin comedy

for Salzburg University,

with five singing

personae. The original

score had 162 pages.

Written in [Wolfgang's]

eleventh year 1767'.

Salzburg University was

run by the Benedictines,

who, in their schools,

had long had the custom

of mounting plays,

operas and even ballets

on morally edifying

themes. In this

instance, a spoken

tragedy was being

staged, and Mozart’s

'opera' was, in the

18th-century manner, divided

into three portions,

which were used as a

prologue and as

intermezzos between the

acts of the tragedy.

Apollo and Hyacinth

was performed by

students and teachers in

the Great Hall of the

University on 13 May.

Although it seems to

have been well received,

there is no record of

further performances.

The libretto, in Latin

and in the style of the

Italian opera librettos

of the day, relates the

story found in Ovid and

elsewhere of Apollo's

accidental slaying of

the youth Hyacinth,

whose blood was

transformed into the

flower that bears his

name. The work's

overture, or 'Intrada'

as Mozart labelled it,

is listed as an

independent 'Sinfonia'

in an early 19th-century

Breitkopf & Härtel

manuscript catalogue.

The single-movement

work, in 3/4

and marked allegro, is

even briefer than the

previous symphony. Like

that work this too is in

binary form, but with

only the first half

repeated. Saint-Foix

remarks upon the work's

'symphonic' character.

This may refer to the

nearly total absence of

cantabile melody in this

'Sinfonia',

with its scales,

arpeggios, syncopations,

repeated notes and

fanfares. All in all, a

happy noise for a

festive occasion.

Apollo and Hyacinth

has one further

symphonic connection: a

duet from it (No. 8, 'Natus

cadit') was

itself transformed by

Mozart into the slow

movement of the Symphony

in F major, K. 43

(concerning which see

Box 7 of this series of

recordings).

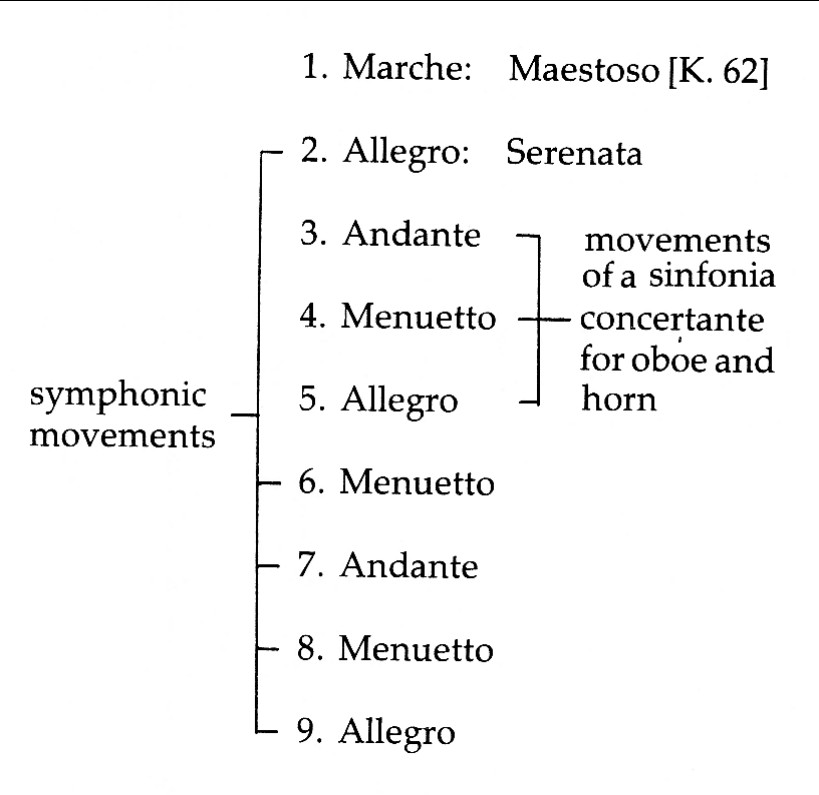

Symphony in D major,

K. 62a (100)

This symphony was

extracted from an

orchestral serenade - a

logical procedure given

that the occasions for

serenades and for

symphonies were quite

different, and that

serenades were made up

of interlarded symphony

and concerto movements

prefaced by a march. In

the present case the

interpenetration of the

constituent genres is as

follows:

The undated autograph

manuscript of the

serenade is found among

an important group of

manuscripts that was in

Berlin until World War II

and is now in Kraków.

The work is lacking in

Leopold's 1768 catalogue

of his son's works and

mentioned by Wolfgang

himself in a letter of

August 1770, so these

two documents provide us

with termini a quo

and ad quem. The

large scale of the piece

and the presence of

trumpets and kettledrums

suggest that it was

intended for a

celebration at court,

and not (as is usually

stated) as a 'Finalmusik'

for the end of the

summer term at Salzburg

University.

This is one of five

Mozart serenades that

exist in symphony

versions. For three of

the five there are

extant sets of

orchestral parts of the

symphony version at

least partially in

Leopold's or Wolfgang's

hand, making clear that

they themselves were

involved in the

redaction. In the

remaining two cases

(including the one at

hand) we have only

copyists’ manuscripts,

but there seems every

reason to believe (by

analogy with the other

three) that these too

stem from originals

coming from Mozart or

his immediate circle.

The symphony version of

K. 62a was perhaps for

use in Salzburg, but may

also have been intended

for Mozart’s first trip

to Italy, begun on 13

December 1769. It was

the Mozarts’ custom when

travelling to give

concerts in the cities

they visited, both to

promote Wolfgang's

reputation and to help

finance the journey. We

note, for instance, that

Wolfgang gave public

concerts in Innsbruck

(17 December), Rovereto

(25 December), Verona (5

January),

Mantua (16 January),

Milan (23 February),

Bologna (26 March),

Florence (2 April),

etc.. The programme in

Mantua is known, and it

included two symphonies

by Mozart. The

programmes of the other

concerts have not come

down to us, but some

them undoubtedly also

included symphonies. It

was not until August

1770 that Mozart wrote

home to Salzburg from

Bologna announcing, 'I

have already composed

four Italian

symphonies’. This

suggests that he had

previously been using

Salzburg symphonies

brought along for the

purpose, and K. 62a may

well have been among

them.

Concerning the first

movement- a commontime

allegro - Günter

Hausswald has written of

'the echoes of a

festive, boisterous

opera overture on the

Italian model'.

Characteristics of this

style are, he continues,

thematic material built

on broken triads and

fanfare-like ideas, as

well as 'a true al

fresco style worked into

a large-scale

overall structure'. The

melodies are

'essentially

conventional and

traditional in scope',

and 'limited to repeated

broken chords; to

rigidly maintained

chains of scales; to

instrumentally

idiomatic, free

figuration; to

punctuating chords. Only

two subsidiary ideas

reveal an individual

profile'. Lurking behind

Hausswald's description

of the movement one

senses disapproval of

what he considered to be

a lack of originality

and of singable melody.

But the 18th century was

much more interested in

suitability than in

originality, and the

lack of vocal melody

places the movement in

the category of abstract

art, a category with

which aestheticians of

both the 18th and 20th

centuries have had

difficulties. In the

former period Leopold

Mozart referred to

symphonies by J.

Stamitz in the abstract

vein as 'nothing but

noise', and

the writer Lacépède

tried to cope with the

problem by requiring

that symphonies have

programmes. Linguistic

analogies, beloved of

20th-century analysts,

which speak of phrases,

sentences and

paragraphs, break down

in the face of works

that would appear to be

composed largely of

conjunctions,

prepositions and

articles. Detlef Schultz

dismisses such movements

as 'purely decorative'

which, like Hausswald's

remarks, seems to hint

at a perceived 'lack of

meaning'. Here we have

an aspect of musical

creativity in which

practice has far

outstripped the ability

of theory to explain it.

The minuet that follows

is also based upon

fanfares and scales. Its

opening idea seems

tongue-in-cheek, perhaps

because, as Machaut had

a circular creation of

his own proclaim, 'Ma

fin est mon

commencement'. The trio,

in G major and for

strings alone with

divided violas, offers

us a chamber-music

intimacy that contrasts

happily with the pomp of

the minuet.

The marvellous change of

tone evident from the

first note of the

andante (in 2/4 and A

major) is due to a

combination of factors:

the key changes; the

horns, trumpets and

kettledrums have dropped

out; the violins are

muted; the cellos and

basses play pizzicato;

and the oboists would

here have put down their

instruments and taken up

transverse flutes. This

pastoral movement is

dominated by the sound

of the flutes, whether

sustaining slowly

changing harmonies or

adding melodic fillips.

A second minuet exhibits

less pomp than the

first, though with even

more scales. The trio,

again for strings alone

but now in D minor,

makes much. of joking

grace notes and the

slapstick comedy of high

versus low and loud

versus soft. Hausswald

calls the trio 'scherzolike'.

The finale, a jig in the

form of a rondo. brings

the festivities to a

suitably lively

conclusion. Its

principal theme, which

occurs no fewer than

fourteen times, bears a

passing resèmblance

to the popular German

round Am Abend,

the first line of which

is 'O wie wohl ist mir

am Abend' and

which in

English-speaking

countries is known by

the words 'O how lovely

is the evening'.

The author of this tune

is said to be one K.

Schulz. Can this be the

Karl Schulz who was a

tenor and voice teacher

at the Salzburg

Cathedral during the

periods 1769-79 and

1783-87? On the other

hand, the principal

theme also resembles the

hunting call entitled

'Le vol-ce-l'est'.

According to an

18th-century treatise on

hunting, 'One sounds

this fanfare when one

again sees the hunted

stag'. The

likelihood is that these

three tunes are not

directly related, but

have common antecedents.

Symphony in C major,

K. 73

The autograph manuscript

of this work, also

formerly in Berlin and

now at Kraków,

bears only the

inscription 'Sinfonie'

in Mozart’s hand. The

date '1769'

was added in a later

hand, perhaps Leopold's.

Köchel

accepted that date and

the editors of the sixth

edition of his catalogue

have reverted to the

same date, thus calling

into question Alfred

Einstein's assignment of

the work in the third

edition to the summer of

1771. It is due to

Einstein's attempted

redating (accepted by

Saint-Foix) that this

symphony will

occasionally be found

designated as K. 75a. As

a sketch for the minuet

of this symphony is

found in the autograph

of a series of minuets

(K. 61d/103) that Mozart

is thought to have

written for Carnival

1769, the symphony may

have been completed

around that time and the

Köchel

number 73 would

therefore be too high.

The error of Einstein’s

proposed redating is

confirmed by another

manuscript, which

originated as an attempt

by Leopold to copy out a

bass part for this

symphony. For unknown

reasons Leopold

abandoned his effort

after only 12 bars, and

Wolfgang later used the

largely empty sheet of

music paper to resolve a

puzzle canon from Padre

Martini's Storia

della musica,

a book which came into

the Mozarts’ possession

in early October 1770.

Wyzewa and Saint-Foix

comment on the Germanic

character of the first

three movements of this

work. Abert considers

the opening idea of the

first movement to be

strongly influenced by

the Mannheim School of

symphonies. Schultz puts

the matter somewhat

differently, writing of

the opening that 'the

principal theme departs

from the overture-type.

It is a hybrid form in

which a first phrase,

built of chordal

figurations in the

Italian style, gives way

to a cantabile phrase in

a manner unknown to the

theatre symphony. In

other respects the

movement still bears a

pronounced overture

character'.

It is perhaps indicative

of the movement's hybrid

nature that, even though

the symphony as a whole

is a four-movement

concert symphony along

Germanic lines rather

than a three-movement

Italianate

overture-symphony, the

first movement's two

main sections are (in

the Italian manner) not

repeated.

The andante - a binary

movement in F major and

2/4- is treated

similarly to that of the

previous symphony: the

horns, trumpets and

kettledrums drop out and

the oboists take up

their flutes. Larsen

singles out this

movement from among all

of Mozart’s symphonies

of this period 'for its

fine cantabile, and even

more for the short

dialogue between first

violins and first

flute'.

Wyzewa and Saint-Foix

find the stately minuet

Haydnesque (Joseph,

not Michael), and

especially the trio

which is for strings

alone. The finale shows

French influence, as

they point out, and is

in fact a contredanse

en rondeau. The

movement is marked

allegro molto 2/4, but

one can sense the

moderato gavotte

underlying the rondo

theme by beating time

only once a bar,

starting with an upbeat.

Although the finale is

176 bars long, Mozart

wrote out only eight

brief passages totalling

72 bars. These eight

passages he numbered in

such a way that an alert

copyist could piece

together the whole

movement. (Over the

first passage, for

instance, he wrote ’1 2

5 6 8 9 16 17’, thus

indicating the position

of its eight

appearances.) Mozart’s

method of abbreviation

saved him time, paper

and ink; it also permits

us a clear vision of the

extent to which he had

the structure of the

movement in his mind

before he wrote it down.

Symphony

in D minor, K. 74c

(118)

Leopold and Wolfgang

Mozart spent a single

day (13 March 1771) in

Padua on the way home

from a triumphant

Italian tour. They had

hoped to be mere

tourists but news of

their presence leaked

out immediately and

Wolfgang had to perform

at two noble homes. As a

result, he was

commissioned by a local

nobleman, Don Giuseppe

Ximenes, Prince of

Aragon, to set

Metastasio’s 1734

oratorio text, La

Betulia liberata.

The work was apparently

completed by the summer

of 1771. In a letter of

19 July to

an Italian patron,

Leopold reported his

plan to send the

manuscript to Padua on

the way south to Milan

in August, in order to

permit the oratorio to

be copied; and on the

return journey, to visit

the town in order to

listen to a rehearsal.

We never learn why these

plans fell through, but

the Mozarts did not

revisit Padua, and the

Paduans performed

another setting of the

same libretto,

apparently by the local

composer Giuseppe

Calegari. Furthermore,

there is no evidence

that Mozart’s oratorio

was performed in Padua

or in Salzburg at a

later date, nor can

vague reports of

performances in Munich

in 1775 or Vienna in

1786 be substantiated.

Hence this major work of

Mozart’s youth may have

remained unperformed

during his lifetime.

The symphony at hand was

intended to serve La

Betulia

liberata

as its overture. It is a

work well written from

beginning to end that

deserves to be better

known. Aspects of the

more famous 'Little' G

minor symphony, K.

173dB/183, that have

fascinated commentators

(see Box 4) are present

in this work of two

years earlier. The

marvellous sounds found

in the efflorescence of

minor-key symphonies of

the early 1770s by

Mozart, Dittersdorf, J.

Haydn, Vanhal, and Ordoñez

were not entirely new.

The opera house had long

required such

tempestuous effects to

portray both the storms

of nature and those of

human emotions. The

young Mozart was

familiar with this style

some years before he

composed K. 74c, for

when he was staying in

Chelsea in 1764 he had

sketched into a notebook

a G minor keyboard

piece, K. 15p, in a

quasi-orchestral style,

which already captured

the stormy character

that has erroneously

been claimed as an

innovation of the 1770s.

Luigi Tagliavini, the

editor of Betulia

for the NMA,

writes that the overture

'introduces the

atmosphere of the

'Azione Sacra'.

This recalls Kirnberger's

description of the

symphony as'...

particularly suited to

the expression of

greatness, solemnity,

and stateliness. Its

purpose is to prepare

the listener for the

important music that

follows... If it is to

carry out this purpose

adequately and become

part of the opera or

church music that it

precedes, then, besides

an expression of

greatness and solemnity,

it must also have a

character that puts the

listener in the proper

frame of mind for the

piece to follow...'.

Metastasio's story is

drawn from the

Apocrypha. Its central

figure is Judith

who, when the Jewish

city of Betulia was

under siege by the

Assyrians and nearing

surrender, left the city

and sought out the enemy

commander, Holofernes.

In pretending to seduce

him, she managed to

behead the disarmed

commander. The Assyrians

withdrew and Betulia was

spared.

Mozart’s 'Overtura'

consists of three

sections, in common

time, 3/4, and

2/4, but without tempo

indications. These

sections are usually

interpreted by

performers and editors

as a ponderous allegro,

a flowing but poignant

andante, and a fiery

presto - by analogy with

other sinfonias of this

structure. The first and

last sections are based

upon the same thematic

material and, in fact,

the 3/4 section may be

viewed as an

interruption.

It is probably no

coincidence that this

work is in the same key

as the overture to

Gluck's Alceste

(1767) and shares with

it a rising third

motive. The Mozarts were

familiar with Gluck's

opera, which figures in

their correspondence as

early as February 1768.

Symphony in F major,

K. 75

An autograph of this

symphony is unknown. The

work cannot have been

widely circulated in the

18th century, for it

survived only in a

single set of manuscript

parts in the Breitkopf

archives in Leipzig. Köchel

assigned the symphony to

the summer of 1771,

which Mozart spent in

Salzburg between his

first and second trips

to Italy, and neither

this date nor the

authenticity of the work

has ever been

challenged. The need for

new symphonies was

constant, for aside from

his participation in the

continuing music at

court, Mozart gave

'academies' (as concerts

were called) in Salzburg

that summer, as well as

in Rovereto (17 August),

Milan (22 November) and

Brixen (11 December).

The present symphony may

have figured in those

activities. It is scored

for the standard small

orchestra of the period:

strings with pairs of

oboes and horns, and

harpsichord and bassoons

added to the bass line.

The opening of the 3/4

allegro is an unusual

composite idea formed

from turns (gruppettos)

in the first violins

connected by rising

arpeggios in the oboes.

This is extended by

energetic 'motor

rhythms' of Vivaldian

descent, which feature

anapaestic patterns. All

of the material of this

lively ternary movement

is thus accounted for

except for the

twenty-bar middle

section, which is

developmental in

character and begins

with a fugato on a new

theme, though this soon

lapses into homophony.

As in the previous

symphony, there are no

repeated sections.

The minuet is unusual in

at least two regards: it

occupies the second

rather than the third

position in the

four-movement scheme and

it is filled with slurs.

Symphonic minuets, which

trace their descent from

French ball-room and

stage dances, are

usually in a more

detached, staccato,

rhythmic style, rather

than the legato,

cantabile style

associated with Italian

music. This example,

however, leans in the

cantabile direction. The

trio, for strings alone,

is thematically related

to the opening of the

first movement.

The andantino, like many

of Mozart’s of this

period, is in 2/4 with

the violins muted. In

addition the horns drop

out and the key changes

to Bb major. The

character is that of an

Italian cantabile aria,

worked into a

rounded-binary movement

with both sections

repeated. The two

sections end with the

same material, and the

delicate way in which

Mozart ornaments those

ideas at the end of the

second section is an

especially fine touch.

The 3/8 finale seems to

have confounded the

critics. The Köchel

catalogue gratuitously

labels it 'rondeau',

which it most assuredly

is not. Wyzewa and

Saint-Foix believe that

the opening theme

exhibits the character

of a French dance, while

Abert is equally certain

that it is based upon a

German folk dance.

Neither the Frenchmen

nor the German offers an

example for comparison.

The idea itself has the

special feature of an

unexpected pause, which

in a most attractive way

turns what the ear

expects will be an

ordinary eight-bar

phrase into a nine-bar

one. (The nature of the

pause will be familiar

to those who recall

Brahms' Hungarian Dance

No. 6 in Db major.)

Nationality aside, there

is at least agreement on

the high spirits and

dance-like nature of the

finale. The movement is

in rounded-binary form,

influenced by

rudimentary sonata-form,

with both sections

repeated.

Symphony

in G major, K. 75b

(110)

The autograph

manuscript of this

symphony, along with

several others, was

previously in Berlin

and is now in Kraków.

Mozart headed it,

'Sinfonia del Sgr.

Cavaliere Amadeo

Wolfg. Mozart in

Salisburgo nel Luglio

1771'. The title

'Cavaliere'

refers to a knighthood

within the Grder of

the Golden Spur, which

the Pope had conferred

upon the

fourteen-year-old

prodigy in Rome in July

1770. A year later

plans were already

well advanced for the

second trip to Italy,

and this symphony,

like the previous one,

was perhaps assigned

the double role of

providing material for

a final round of

music-making in

Salzburg and for

'academies' in Italy.

A work usually

receives a new Köchel

number only when new

evidence emerges

suggesting a changed

date of origin. In the

present instance,

however, revisions to

Köchel's

original chronology

for 1771 were so

extensive (many works

were found to be in

the wrong order,

assigned to the wrong

year, or even

spurious), that an

almost entirely new

chronology had to be

worked out. When the

dust settled, it was

no longer possible to

use the number 110 for

this symphony, and it

acquired the new

number 75b, without

its date of

composition, July

1771, altering.

It is difficult to

regard this symphony

as coming from the

same creative impulse

as the previous two. It

is worked out on a

much grander scale and

apparently with more

care. This is manifest

in all movements in

the more contrapuntal

writing of the inner

parts and, especially,

of the bass line.

The opening allegro 3/4

is more than twice as

long as the previous

first movements, if

the repeats of both

sections are observed.

Rather exceptionally

for Mozart, the

movement tends toward

the monothematic. That

is, the opening idea

reappears (somewhat

transformed) in the

dominant as a 'second

subject' and again in

its original guise in

the closing section of

the exposition. The

development section is

based on an

imitatively-treated

descending scale, and

this is followed by

striding quavers in

the bass (an idea

previously heard in

the closing section of

the exposition). The

recapitulation is far

from literal, with the

bridge-passage

extended in a

developmental way. The

monothematicism and

the introduction of

developmental aspects

in the recapitulation

are relatively unusual

for Mozart but common

for Joseph

Haydn, whose influence

has also been noted

elsewhere in the

symphony.

The second movement,

in C major and alla

breve, bears no tempo

indication, although

it is clearly an

andante or andantino.

The oboes are replaced

by flutes, and a pair

of bassoons -

previously and

subsequently subsumed

along with the cellos,

double basses and

harpsichord under the

rubric 'basso'

- suddenly blossoms

forth with obbligato

parts. If the movement

had been given a

title, it might have

been 'Romanza'. The

romanza, or romance

(to give it its

English and French

form), was a strophic

poem telling a gallant

love story set in

olden times. In

mid-18th-century Paris

it began to be set to

simple folk-like

melodies for use in

salons and in stage

works. This style of

music was soon

transferred to

instrumental music.

Gossec first used a

romance in a symphony

around 1761, as did

Dittersdorf in Vienna,

in 1773. Mozart has

taken the mock-naïve

musical style of the

romance in the

'simple' key of C

major, and worked it

into a sonata-form

movement with two

repeated sections.

Most of the movement's

two-bar phrases are

immediately repeated,

creating a kind of

musical construction

that the French called

'couplets'. The great

care with which the

inner parts of this

usually homophonic

style are worked out,

however, reveals a

craftsman in the

German tradition. An

especially effective

colouristic touch is

the major chord built

upon the flattened

sixth degree of the

scale, which sounds

twice near the end of

each section.

The minuet is canonic,

and commentators again

see the influence of

Haydn, who wrote

canonic minuets in

several symphonies of

the period. Mozart’s

aggressively striding

minuet is nicely

contrasted with the

more sedate E minor

trio, for strings

alone. The Köchel

catalogue claims that

the da capo of the

minuet is fully

written out in

Mozart’s autograph;

this is not correct,

and would have been

most atypical of

Mozart who customarily

used every possible

abbreviation and

short-cut when writing

down his compositions.

The finale, like that

of K. 73, is a 2/4

allegro in which one

can sense the gavotte

or contredanse

underlying the theme

by beating time at

half speed (once in a

bar) beginning with an

upbeat. This rondo has

a striking middle

section (itself binary

in structure) in G

minor that is rather

exotic in character

and nicely sets off

the courtly dance that

surrounds it.

Symphony

in A major, K.114

This is the first of a

series of eight fine

symphonies written for

Salzburg in the period

of less than a year

between the Mozarts’

second and third

Italian trips. It

marks the onset of

what Mila has dubbed

'symphonic fever', for

in the period 1770-75

Mozart composed no

fewer than thirty-six

symphonies. There were

undoubtedly practical

motives behind this

outpouring of

symphonies in addition

to artistic ones. The

Italian trips had not

proved as lucrative as

Leopold had hoped, and

he had been denied a

portion of his salary

during his absence. It

was time for him and

his son to settle down

at home in order to

pay off their debts.

Archbishop Sigismund

Christoph von

Schrattenbach died in

December 1771, a few

days after the Mozarts

returned to Salzburg.

Much music was needed

for the period of

mourning, for

Carnival, for Lent,

and for the

installation of the

new archbishop in

April. In addition,

Mozart sought a

promotion, for his

title of concert

master was honorary -

that is to say, unpaid

Having proved his

mettle with Il

sogno di Scipione,

the sixteen-year-old

became a regularly

paid member of the

court orchestra on 9 July

1772, at the modest

annual salary of 150

florins.

Mozart and his father

returned from Italy on

15 December 1771, and

the autograph

manuscript of this

symphony - once again

found among the

Berlin-Kraków

material - is dated a

fortnight later. This

then must be a work

for the muted

festivities of

Carnival 1772.

Several commentators

suggest that in this

symphony Mozart

declares himself for

the 'Viennese'

symphonic style, while

still retaining

important Italian

elements. This refers

to the greater length,

the more extensive use

of wind instruments,

the more contrapuntal

texture, the

four-movement format,

and the greater use of

non-cantabile thematic

materials. Larsen

considers this

symphony 'one of the

most inspired of the

period. One could

point out many

beauties in this work,

such as the

developmental

transition, the second

subject with its hint

of quartet style, and

the short, but

delicately wrought

development with

elegant wind and

string dialogue'. Even

the opening bars,

which forgo loud

chords or fanfares and

begin piano, suggest

something new. Schultz

thought the first

theme to be 'Viennese'

in style but, in fact,

with its mid-bar

syncopation, it is

closer to the style of

J.

C. Bach. Mozart heard

Bach's symphonies in

London in 1764-65, and

there is evidence that

they were also

performed in Salzburg

in the early 1770s.

This movement exhibits

that fullness of ideas

which was noted as a

hallmark of Mozart’s

style as early as

1792, and which Larsen

describes with

reference to this work

as 'the dominant

tendency' to present

'a whole series of

fine cantabile themes:

symphonic development

results from their

interplay and

contrast'. Perhaps the

only conservative

trait of this inspired

and otherwise

forward-looking

movement is the

concertante, rather

than symphonic,

handling of the winds

in the development

section.

In the previous

symphonies the oboists

were required in the

andante to take up

flutes; here the

reverse is the case,

oboes replacing flutes

and the horns falling

silent. The movement,

in 3/4 instead of the

more usual 2/4, is in

sonata form with both

sections repeated. The

violas, which had

already made an

appearance divisi

in the development

section of the first

movement, here provide

an important series of

duets, often doubling

the oboes at the

octave below or

engaging in dialogue

with them. Schultz

considered the

movement the

'highpoint'

of Mozart’s symphonic

andantes up to this

point in his career.

Its most curious

feature is the

development section

which, written in

continuous quavers,

gives the impression

of a

not-quite-convincing

Baroque Fortspinnung

in the midst of the

modern periodic style

of the exposition and

recapitulation.

The editors of both

the NMA and Mozart-Handbuch

claim that an

unattached A major

minuet, K.

61gI, was originally

intended by Mozart for

this symphony. That

cannot be right,

however, because the

work in question

probably dates from as

early as 1770 and

lacks the pair of

horns called for by K.

114. When Einstein

examined the autograph

manuscript of K. 114

prior to 1936, he

found there another,

fully-scored minuet

that Mozart had

crossed out. The

opening theme of the

rejected minuet

(reproduced in the Köchel

catalogue) is a

reworking of the theme

of the andante. Could

this have been the

reason that Mozart

crossed it out and

inserted the present

minuet? In any case,

the present minuet is

a particularly

stately, old-fashioned

one, spiced with some

implied secondary-dominant

chords near the end of

each section. Its

trio, in A minor, is

in a mock-pathetic

vein. The

repeated-note melody,

on the fifth degree of

the scale rising a

semitone to the sixth,

is a melodic shape

familiar to Mozart

from the plainchant

setting of the sombre

Holy Week text Miserere

mei, Deus. The

mocking comes from the

second violins, who

gad about with their

triplets and trills as

if they were making

variations on a comic

opera tune.

The finale, molto

allegro 2/4,

begins with a brief

fanfare once repeated.

Remarkably, however,

instead of introducing

a theme, Mozart then

has the orchestra

play, twice and in a

conspicuous manner,

the harmony primer

chordprogression:

I-IV-V-I. This is the

so-called

’bergamasca’, a kind

of dance or song in

which a melody is

composed or improvised

over many repetitions

of these four chords.

In German-speaking

countries the most

common text sung in

this fashion was

’Kraut und Rüben’,

which runs this way:

Cabbages and turnips

drove me away.

Had my mother cooked

some meat,

Then I'd

have stayed longer.

Mozart does not quote

the 'Kraut und Rüben'

tune, however, and we

do not know what the

purpose of his joke

may have been, though

its very presence

would seem to

reinforce our

suggestion that this

symphony was composed

with Carnival in mind.

The rest of the

movement, in sonata

form with both

sections repeated, is

also in high, if more

conventionally

symphonic, spirits.

All this reminds us of

the description of

Salzburg by a German

visitor of the

mid-1770s:

'Here everyone

breathes the spirit of

fun and mirth. People

smoke, dance, make

music, make love, and

indulge in riotous

revelry, and I have

yet to see another

place where one can

with so little money

enjoy so much

sensuousness'.

Symphony in G

major, K. 124

Carnival ends on Mardi

Gras and with the next

day, Ash Wednesday,

Lent begins. In 1772

these days fell on 3

and 4 February

respectively. Mozart

wrote at the top of

this symphony (also in

the Berlin-Kraków

collection), 'Sinfonia

del Sigr. Cavaliere

Wolfgang Amadeo Mozart

Salisburgo 21 Febrario

1772'.

Hence we may have a

work intended for a

Lenten concert

spirituel. On

the other hand, Mozart

may equally have been

preparing works for

the new archbishop,

who took office on 29

April. The archbishop

was a competent

amateur violinist who

liked to join his

orchestra in

performances of

symphonies, standing

next to the concert