|

|

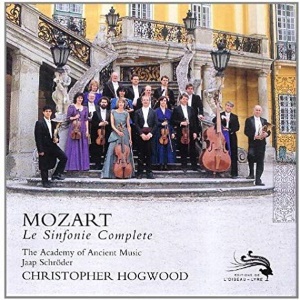

3 LP's

- D167D3 - (p) 1982

|

|

| 2 CD's -

417 140-2 - (c) 1986 |

|

| 19 CD's

- 480 2577 - (p & c) 2009 |

|

| The Symphonies

- Vol. 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wolfgang

Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

46' 52" |

|

| Symphony No. 1 in

E flat Major, K. 16 |

12' 53" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro molto · Andante · Presto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 4 in D Major, K. 19 |

8' 52" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante · Presto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

in F Major, K. 19a / Anh. 223 |

13' 26" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro assai · Andante · Presto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 5 in B flat Major, K. 22 |

6' 35" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante · Allegro molto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 32 |

5' 06" |

|

|

| -

[Molto allegro · Andante · Menuetto

& Trio · Finale] |

|

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

48' 09" |

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 97 / K. 73m |

10' 29" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Presto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 95 / K. 73n |

12' 38" |

|

|

| - [Allegro - ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

in D Major, K. 81 / K. 73l |

11' 16" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Allegro molto] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 10 in G Major, K. 74 |

7' 55" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro-Andante · Rondeau

(Allegro)] |

|

|

|

Symphony

in D Major, K. 87 / K. 74a

|

5' 51" |

|

|

| -

[Allegro · Andante grazioso ·

Presto] |

|

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

43' 48" |

|

| Symphony

No. 11 in D Major, K. 84 / K. 73q |

8' 51" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Allegro] |

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 13 in F Major, K. 112 |

15' 05" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro molto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

in D Major, K. 120 / K. 111 / K.

111a

|

6' 24"

|

|

|

| - [Allegro assai ·

Andante grazioso · Presto] |

|

|

|

Symphony

in C Major, K. 96 / K. 111b

|

13' 28" |

|

|

| - [Allegro ·

Andante · Menuetto & Trio ·

Allegro molto] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE ACADEMY OF ANCIENT MUSIC

(on authentic instruments) A=430 - directed

by

|

|

| Jaap Schröder,

Concert Master |

|

| Christopher

Hogwood, Continuo |

|

|

|

|

|

| Violins |

Japp

Schröder

(Antonio Stradivarius 1709) - Catherine

Mackintosh (Rowland Ross 1978

[Amati] & Ian Boumeester,

Amsterdam 1669) - Simon Standage

(Rogeri, Brescia 1699) - Monica

Huggett (Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - Elizabeth Wilcock

(Grancino, Cremona 1652) - Roy

Goodman

(Rowland Ross 1977

[Stradivarius]) - David Woodcock (Anon. circa

1775) - Joan

Brickley

(Mittewald,

circa 1780) -

Alison Bury

(Anon.

England, circa

1730) - Judith

Falkus

(Eberle,

Prague 1733) -

Christopher

Hirons

(Duke, circa

1775) - John

Holloway

(Sebastian

Kloz 1750

& Mariani

1650) - Polly

Waterfield

( Rowland Ross

1979 [Amati])

- Micaela

Comberti

(Anon. England

circa 1740) -

Miles

Golding

(Anon.

Austria, circa

1780 &

Roze, Orleans

1756) - Kay

Usher

(Anon.

England, circa

1750) - Julie Miller (Anon. France,

circa 1745

& Rowland

Ros 1979

[Amati]) - Susan

Carpenter-Jacobs

(Jacobs-Franco

Giraud 1978 [Amati]

& Rowland Ross

1979 [Amati]) - Robin Stowell (David

Hopf, circa

1780) - Richard

Walz

(David Rubio

1977

[Stradivarius])

- Judith Garside (Anon.

France, circa

1730 &

Joseph

Hill(?),

London 1766) -

Rachel

Isserlis

(John Johnson

1759) - Robert

Hope Simpson

(Samuel

Collier, circa

1740) - Catherine

Weiss

(Rowland Ross

1977

[Stradivarius])

- Jennifer

Helsham

(Alan Bevitt

1979

[Stradivarius])

- Jane

Debenham

(Anon. German,

18th century)

- Roy

Howat

(Henry

Rawlins,

London Bridge

1775) - Christel

Wiehe

(John Johnson,

London 1759) -

Roy Mowatt

(Rowland Ross

1979

[Stradivarius])

- Roderick

Skeaping

(Rowland Ross

1976 [Amati])

- Eleanor

Sloan

(German(?),

circa 1790) -

June Baines

(Nicholas

Amati 1681) -

Stuart

Deeks

(Saxon, circa

1770) - Graham Cracknell (Anon.

England 1780)

|

|

|

|

|

| Violas |

Jan Schlapp

(Joseph Hill 1770) - Trevor Jones

(Rowland Ross 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Katherine

Hart (Charles and Samuel Thompson

1750) - Colin Kitching (Rowland Ross

1978 [Stradivarius]) - Nicola Cleminson

(McDonnel, Ireland, circa 1760) - Philip

Wilby (Carrass Topham 1974 [Gasparo da

Salo]) - Annette Isserlis (Ian

Clarke 1978 [Guarnieri]) - Simon

Rowland-Jones (Anon. England, circa

1810) - Judith Garside (Hill School,

England 1766) |

|

|

|

|

| Violoncellos

|

Anthony Pleeth

(David Rubio 1977 [Stradivarius]) - Richard

Webb (David Rubio 1975 [Januarius

Gagliano]) - Mark Cuadle (Anon.

England, circa 1700) - Juliet Lehwalder

(Jacob Haynes 1745) - Susan Sheppard

(Peter Walmsley 1740)

|

|

|

|

|

| Double

Basses |

Barry

Guy (The Tarisio, Gasparo da

Salo 1560) - Peter McCarthy

(David Techler, circa 1725 &

Anon. England, circa 1770) - Keith

Marjoram (Anon., Italy circa

1560) |

|

|

|

|

Flutes

|

Stephen

Preston (Anon. France, circa

1790) - Nicholas McGegan

(George Astor, circa 1790) - Lisa

Beznosiuk (Goulding, London,

circa 1805) - Guy Williams

(Monzani, circa 1800) |

|

|

|

|

| Oboes |

Stanley

King (Rudolf Tutz 1978

[Grundmann]) - Clare Shanks

(W. Milhouse, circa 1760) - Sophia

McKenna (W. Milhouse, circa

1760) - David Reichenberg

(Harry Vas Dias 1978 [Grassi]) - Robin

Canter (Kusder, circa 1780)

|

|

|

|

|

Bassoons

|

Jeremy

Ward (Porthaus, Paris, circa

1780) - Felix Warnock

(Savary jeune 1820) - Alastair

Mitchell (W. Milhouse, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Horns |

William

Prince (Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Keith Maries (Anon.

Germany(?) circa 1785 & Courtois

neveu, circa 1800) - Christian

Rutherford (Kelhermann, Paris

1810 & Courtois neveu, circa

1800) - Roderick Shaw

(Raoux, circa 1830) - John

Humphries (Halari, 1825) - Patrick

Garvey (Leopold Uhlmann, circa

1810) |

|

|

|

|

| Natural

Trumpets |

Michael

Laird (Laird 1977, German) - Iaan

Wilson (Laird 1977, German) -

Stephen Keavy (Keavy 1979,

German)

|

|

|

|

|

| Timpani |

David

Corkhill (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1890) - Charles

Fullbrook (Hawkes & Son,

circa 1890) |

|

|

|

|

| Harpsichord |

Christopher

Hogwood, Nicholas McGegan, David

Roblou (Thomas Culliford,

London 1782 & Rainer Schutze

1968 & Jacobus Kirckman 1766) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.

Jude-On-The-Hill, London (United

Kingdom):

- maggio 1980 (K. 16, 19, 22, 32,

74, 87)

Kingsway Hall, London (United

Kingdom):

- settembre 1980 (K. 97, 95, 120,

96)

- novembre 1981 (K. 19a)

St. Jude's, Hampstead Garden

Suburb, London (United Kingdom):

- dicembre 1979 (K. 81, 84, 112)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

Peter

Wadland & Morten Winding /

John Dunkerley & Simon Eadon |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - D167D3 (3 LP's) - durata

46' 52" | 48' 09" | 43' 48" - (p)

1982 - Analogico

|

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Oiseau

Lyre - 417 140-2 (2 CD's) - durata

68' 02" | 70' 27" - (c) 1986 - ADD |

|

|

Edizione Integrale CD |

|

Decca

(Editions de l'Oiseau-Lyre) - 480

2577 (19 CD's) - (p & c) 2009

- ADD / DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mozart

and the symphonic

traditions of his

time by Neal

Zaslaw

The London

Symphonies

Leopold

Mozart realized early that

he had on

his hands what he

later referred to as "the

miracle that God permitted

to be born in Salzburg."

Acting with vigour and

imagination to carry out

what he conceived to be a

sacred trust, he virtually

abandoned the furtherment

of his own career in order

to devote himself to his

son’s education. This

meant, among other things,

that from January

1762 when little Wolfgang

was just turning six, the

Mozart family was

frequently on the road,

visiting the courts and

musical cenhes of western

Europe. These trips were

intended to raise money,

to spread the fame of the

infant prodigy, and to

educate Wolfgang by

exposing him to the

important music and

musicians of the day. Thus

it was that toward the end

of April 1764 the Mozarts

found themselves in

London. By the beginning

of August the

eight-year-old Wolfgang

had to his credit some

four-dozen unpublished

keyboard pieces, as well

as three collections

published in Paris and

London containing ten

sonatas for keyboard with

violin. How he came to

write his first symphony

was recalled in the years

following his death by his

sister N annerl, herself a

precocious keyboard player

who was thirteen at the

time:

'On

the 5th of August [we] had

to rent a country house in

Chelsea, outside the city

of London, so that father

could recover from a

dangerous throat ailment,

which brought him almost

to death’s door... Our

father lay dangerously

ill; we were forbidden to

touch the keyboard. And

so, in order to occupy

himself, Mozart composed

his first symphony with

all the instruments of the

orchestra, especially

trumpets and kettledrums.

I had to copy it as I sat

at his side. While he

composed and I copied he

said to me, "Remind me to

give the horn something

worthwhile to do!"... At

last after two months, as

father had completely

recovered, [we] returned

to London.'

Leopold and his family

moved back to London

around the end of

September, and Wolfgang

and Nannerl resumed their

round of public and

private concerts and

appearances at Court,

while Wolfgang received

instruction in singing

from the Italian castrato

Giovanni Manzuoli. From 6

February 1765 notices

appeared in London

newspapers for a 'Concert

of Vocal and Instrumental

Music’ for the benefit of

'Miss

MOZART of Twelve and

Master MOZART

of Eight Years of Age;

Prodigies of Nature.'

(Note that Leopold

misrepresented his

children's ages.) On

8 February Leopold wrote

to his Salzburg friend,

patron and landlord,

Lorenz Hagenauer:

'On

the evening of the 15th we

are giving a concert,

which will probably bring

me in about one hundred

and fifty guineas. Whether

I shall still make

anything after that and,

if so, what, I do not

know... Oh, what a lot of

things I have to do. The

symphonies at the concert

will all be by Wolfgang

Mozart. I must copy them

myself, unless I want to

pay one shilling for each

sheet. Copying music is a

very profitable business

here.'

The concert was postponed

until Monday the 18th,

however, because a

performance of Thomas

Ame's oratorio Judith

had been put back from the

7th to the 15th, tying up

some artists upon whose

services the Mozarts had

counted. A second

postponement occurred for

unstated reasons. From 15

February notices appeared

in London newspapers

reading:

'HAYMARKET,

Little Theatre.

THE

CONCERT for the Benefit

of Miss and

Master

MOZART will be certainly

performed

on Thursday the 21st

instant, which

will begin

exactly at six,

which will

not hinder the Nobility

and Gentry

from

meeting in other

Assemblies

on the

same Evening.

Tickets to

be had of Mr. Mozart,

at Mr.

Williamson’s in

Thrift-street,

Soho, and at the said

Theatre.

Tickets

delivered for the 15th

will be admitted.

A Box

Ticket admits two into

the Gallery.

To prevent

Mistakes, the Ladies and

Gentlemen

are

desired to send their

Servants

to keep Places for the

Boxes, and give

their

Names to the Boxkeepers

on

Thursday the 21st in the

Afternoon.

The notices published on

the day of the concert

contained an additional

sentence: 'All

the Overtures [i.e.,

symphonies] will be from

the Composition of these

astonishing Composers, who

are only eight Years old.'

(An

error made Wolfgang and

Nannerl the same age and

both composers.) Some

weeks later Leopold sent

Hagenauer a report of

Wolfgang's symphonic

debut, which,

disappointingly for us,

dealt with financial

rather than artistic

matters:

'My

concert, which I intended

to give on February 15th,

did not take place until

the 21st, and on account

of the number of

entertainments (which

really weary one here) was

not so well attended as I

had hoped. Nevertheless, I

took in about hundred and

thirty guineas. As,

however, the expenses

connected with it amounted

to over twentyseven

guineas, I have not made

much more than one hundred

guineas.'

The programme of 21

February 1765 has not come

down to us, but

extrapolating from

programmes preserved from

similar occasions, we can

make an educated guess

about the shape of the

event. Concerts began and

ended with symphonies,

which might also have been

used to complete the first

half, to launch the

second, or to serve both

purposes. Between the

symphonies there would

have been performances on

the harpsichord or chamber

organ by Wolfgang and

Nannerl, together and

separately, improvised and

prepared. Some of London’s

favourite instrumentalists

and singers would have

contributed solos, as was

the custom at benefit

concerts. (We know which

of the virtuosos active in

London were associated

with the Mozarts because

Leopold listed their names

in his travel diary.) The

symphonies performed on 21

February 1765 must have

been from among K. 16, K.

19, and K. 19a, all of

which are thought to date

from this period in

London. In addition, we

should not rule out of

consideration two other

symphonies (K. 16a and

19b), now lost and known

only from their incipits

in an old Breitkopf

catalogue; these are also

believed to have been

composed by Mozart in

London:

From 11 March a series of

notices appeared in London

newspapers announcing the

Mozarts' final concert

appearance there, on 13

May. The programme again

included 'all the

OVERTURES of this little

Boy’s own Composition'.

As early as 19 May 1763 a

letter from Vienna had

reported that, '...we

fall into utter amazement

on seeing a boy aged six

at the keyboard and

hearing him... accompany

at sight symphonies, arias

and recitatives at the

great concerts...'. That

Wolfgang was not only able

to direct his own

symphonies from the

keyboard but that he did

so in London, is confirmed

by one of Leopold's

newspaper announcements

stating that the concert

of 13 May would 'chiefly

be conducted by his Son.'

Mozart's London

symphonies reveal how

perfectly the boy had

absorbed and could imitate

the most up-to-date,

galant style of the

period. His models were

primarily the cosmopolitan

group of German-speaking

composers active in Paris

and London: Johann

Gottfried Eckard, Leontzi

Honauer, Hermann Friedrich

Raupach, Christian

Hochbrucker and Johann

Schobert in the former

city; Johann

Cluistian Bach and Carl

Friedrich Abel in the

latter. The care with

which the little Mozart

studied one of Abel’s

symphonies is indicated by

the fact that he copied it

out himself. More than a

century later, the

existence of Mozart’s

manuscript of Abel’s

symphony caused it to be

published in the old

Complete Works as one of

Mozarts own early

symphonies (the Symphony

No. 3 in Eb major,

formerly K. 18, now K.

Anh. A51).

Though there is no

evidence for the assertion

that Mozart received

formal instruction from J.

C. Bach, the two were

closely associated in

London and the music of

the older man influenced

the younger throughout his

career. J.

C. Bach

was one of the few

musicians about whom only

praise appears in the

Mozart family

correspondence. When Bach

died, Mozart paid him

tribute in the slow

movement of the piano

concerto, K. 414/385p, and

when Abel died he did

likewise in the finale of

the violin sonata, K. 526

- in each case basing his

memorial on a work by the

man whom he wished to

honour.

We do not know the make-up

of the undoubtedly modest

orchestra that Leopold

Mozart assembled for the

concerts of 21 February

and 13 May 1765, but we do

have information about

other ensembles of the

period. We have therefore

based our interpretation

of Mozart's three London

symphonies on a

characteristic small

English orchestra of the

mid-1760s:

the strings 6-5-2-2-1,

with the necessary wind

(pairs of oboes and horns)

as well as harpsichord

continuo and a bassoon

doubling the bass line.

Symphony in Eb major,

K.16

The manuscript score of

this work is found in the

collection that was in

Berlin until World War II

and is now at Kraków.

Unlike several other very

early works which are in

his father’s hand, this

one is in Wolfgang’s. At

the top of the first page

is written 'Sinfonia,

di Sig. Wolfgang Mozart a

london 1764.' The

manuscript begins tidily,

as if intended to be a

fair copy, but extensive

corrections were then

entered by Mozart in a

larger, cruder hand,

creating the appearance of

work-in-progress. This

symphony has always been

considered Mozart’s first,

but can it really be the

one described in Nannerl’s

account? As we have seen,

Nannerl mentioned that she

copied the symphony and

that it called for

trumpets and kettledrums,

neither condition applying

here. Of course, many

symphonies of the third

quarter of the 18th

century did

circulate shorn of their

trumpet and kettledrum

parts, which were often

considered optional and

sometimes separately

notated and absent from

the score. Mozart’s usual

trrunpet keys were C, D,

and Eb major, so this

symphony could indeed have

included those instruments.

Furthermore, one might

speculate that perhaps

Nannerl did copy a

score but that Wolfgang so

thoroughly revised it that

it became illegible,

forcing him to make

another copy - the one we

now have - before

continuing his revisions.

Another fact, the meaning

of which is still unclear,

is that the cover for the

original parts to the

Symphony in D major, K.

19, has notations on it,

in Leopold’s hand,

indicating that it had

orignally served first as

the cover for parts to a

symphony in F major

(presumably K. 19a) and

then for parts to one in C

major (presrunably the

missing K. 19b) - but

there is no mention of a

symphony in Eb. As for

giving the horn 'something

worthwhile to do,' that

is perhaps satisfied by

the passage in the andante

of K. 16 where the horn

plays the motive do-re-fa-mi,

known to everyone from the

finale of Mozart's 'Jupiter'

symphony. Considering all

of the evidence, however,

we are forced to conclude

that the Eb symphony, K.

16, is probably not the

work described in

Nannerl's anecdote, and

that Mozart's 'first'

symphony must be lost.

The first movement of K.

16 opens with a three-bar

fanfare in octaves,

immediately contrasted

with a quieter eight-bar

series of suspensions, all

of which is repeated. This

leads to a brief agitato

section, and the first

group of ideas is brought

to a close by a cadence on

the dominant. At this

point the wind fall silent

and we hear the initial

idea of the second group,

which is extended by a

passage of rising scales

in the lower strings

accompanied by tremolo in

the violins. A brief coda

concludes the exposition,

which is repeated. The

second half of the

movement, also repeated,

covers the same ground as

the first, working its way

through the dominant (Bb)

and the relative minor (c)

to reach the tonic (Eb)

only at the beginning of

the second group.

The andante - a binary

movement in C minor - is a

remarkably successful bit

of atmospheric writing.

The sustained wind, the

mysterious triplets in the

upper strings, and the

stealthy duplets in the

brass instruments,

combine to create a scene

that would have been

perfectly at home in an

opera of the period,

perhaps to accompany a

clandestine nocturnal

rendezvous.

With the beginning of the

presto, the sun rises and

another fanfare launches

us into a vigorous

jig-like finale in the

form of a simple rondo.

The refrain of the rondo

is committedly

diatonic in character, but

the intervening episodes

are filled with

delightfully piquant

touches of chromaticism in

the latest, most galant

manner.

Those writers who have

been at considerable pains

to point out the great

differences in length,

complexity and originality

between this earliest

surviving symphony of

Mozart and his last, may

have missed a crucial

point: there is little

difference in length,

complexity or originality

between Mozart's K. 16 and

the symphonies of J.

C. Bach’s op. 3 and Abel’s

op. 7, which he took as

his models.

Symphony in D major,

K.19

This symphony survives in

the Bavarian State Library

in Munich as a set of

orchestral parts in

Leopold Mozart's hand, in

the cover mentioned in the

discussion of K. 16. The

manuscript also contains

what is described in the

Mozart literature as a

'keyboard reduction'

of the second and third

movements written in a

childish hand. It is

disputed whether or not

this 'keyboard reduction'

may have been the original

notation from which those

movements were

subsequently orchestrated,

and whether or not the

unidentified hand may be

Nannerl's.

The first movement opens

with the kind of fanfare,

used for signalling by

posthoms or military

trumpets, which never returns.

The timbre of the movement

is noticeably brighter

than that of the previous

symphony, due to the

resonance that D major

gives to the strings. The

movement proceeds on its

extroverted way, in a kind

of march tempo, with no

repeats. An especially

nice touch is the

unanticipated. A sharp

with which the development

section begins.

The andante in G major 2/4

evokes a conventional,

pastoral serenity. Its

'yodelling'

melodies and droning

accompaniments were

undoubtedly intended to

evoke thoughts of hurdy-gurdies

and bagpipes. The finale,

3/8, although marked

presto as in the previous

symphony, is however not

quite as rapid, as the

presence of

demisemiquavers reveals.

It is an energetic binary

movement with both halves

repeated. An occasional

'yodelling'

in the melody ties it to

the previous movement.

Symphony in F major,

K.19a

At the beginning of

February 1981 Mozart

lovers were suprised and

delighted to read in their

newspapers press

dispatches from Munich

describing the rediscovery

of a lost Mozart symphony.

A set of parts in Leopold

Mozart's hand, found among

some private papers,

proved to be the Symphony

in F major, K. 19a, the

existence of which had

been known from the

incipit of its first

movement, which was

notated on the cover of

the Symphony in D, K. 19,

discussed above. That K.

19a was a completed work

and not a fragment had

also been known, because

its incipit occurred in an

early-19th-century Breitkopf

& Härtel

catalogue of manuscripts,

with an indication that

the work was for strings

and pairs of oboes and

homs. The newly-discovered

parts were acquired by the

Bavarian State Library,

and the work has now been

published. It was given

its modern British première

by the Academy of Ancient

Music in a BBC broadcast

of 2 August 1981. Thus a

stroke of good fortune

restores to us a work from

Mozart's London sojourn

thought to be

irretrievably lost.

Leopold entitled the work,

'Sinfonia in F/à /

2 Violinj / 2 Hautb: / 2

Cornj

/ Viola / e / Basso / di

Wolfgango Mozart /

compositore de 9 Añj.'

As Mozart turned nine

years old on 27 January

1765, the creation of the

symphony must be placed

after that date but in

time for either the

concert of 21 February or

that of 13 May. Quite

exceptionally for Mozart's

symphonies, the basso

part is figured throughout

- that is, numerical

symbols indicating which

chords to play have been

provided for the continuo

harpsichordist. (The score

of K. 16 has a very few

figures in its first

movement and none in the

rest; the other symphonies

are unfigured.)

The first movement,

allegro assai in common

time, opens with a broad

melody in the first

violins, accompanied by

sustained harmonies in the

winds, broken chords in

the inner voices, and

repeated notes in the bass

instruments.

A brief but effective bit

of imitative writing then

leads to a cadence on the

dominant and the

introduction of a

contrasting 'second

subject.' Tremolo in the

upper strings accompanying

a triadic, striding bass

line carries us to the

closing subject. The

second half of the

movement presents the same

succession of ideas as the

first, and both halves are

repeated. As the harmonic

movement is from tonic to

dominant in the first

half, and from dominant to

tonic in the second, with

little that could be

described as

'developmental' in the use

of themes or harmonies,

the fomr is closer to

simple binary form than to

sonata fonn as it is

generally understood.

In the second movement,

andante 2/4

in Bb major, the oboes are

silent. Like the first

movement, this consists of

two approximately equal

sections, both repeated.

Although the texture is

simple and the ideas not

unconventional, the

movement exhibits a polish

and élan

quite remarkable in the

work of a child.

The finale is a rondo,

marked presto 3/8. Finales

in 3/8, 6/8, 9/8, or 12/8

were extremely common at

the time this work was

written, and usually took

on the character of an

Italianate giga.

Here, however, little

Wolfgang must have had his

eye on pleasing his

British public, and the

refrain of his rondo has

some of the character of a

highland fling, bringing

the symphony to a suitably

jolly conclusion.

The Dutch Symphonies

The Mozarts' original

intention upon leaving

London was to return

directly to Paris, where

they had left some of

their luggage. Not long

after arriving in London,

Leopold had informed

Hagenauer,'... we shall

not go to Holland, that I

can assure her

[Hagenauer's wife]'. The

Dutch ambassador to the

Court of St. James

sought Leopold out in

Canterbury around 25 July

1765, however, at the

beginning of the Mozarts'

return

journey. As Leopold

later wrote to Hagenauer

from The Hague, the

ambassador 'implored me at

all costs to go to The

Hague, as the Princess of

Weilburg, sister of the

Prince of Orange, was

extremely anxious to see

this child, about whom she

had heard and read so

much. In

short, he and everybody

talked at me so

insistently and the

proposal was so attractive

that I

had to decide to come...'.

The Mozarts remained in

Holland from September

1765 to April 1766.

This detour on their

homeward journey

resulted in performances

in Ghent (5 September),

Antwerp (7 or 8

September), The Hague

(three concerts between 12

and 19 September, *30

September, *22 January),

Amsterdam (*29 January,

26 February), the Hague (*mid-March),

Haarlem (early April),

Amsterdam (16 April), and

Utrecht (*21

April). From newspaper

announcements, archival

documents and

correspondence, we learn

that at least five of

these thirteen

performances (indicated by

asterisks) included

performances of symphonies

by Mozart. A typical

newspaper announcement is

the following, taken from

the 'S-Gravenhaegse

Vrijdagse Courant:

'By permission, Mr.

MOZART, Music Master to

the Prince Archbishop of

Salzburg, will have the

honour of giving, on

Monday, 30 September 1765,

a GRAND CONCERT in the

hall of the Oude

Doelen at The Hague,

at which his son, only 8

years and 8 months old,

and his daughter, 14 years

of age, will play

concertos on the

harpsichord. All the

overtures will be from the

hand of this young

composer, who, never

having found his like, has

had the approbation of the

Courts of Vienna,

Versailles and London.

Music-lovers may confront

him with any music at

will, and he will play

everything at sight.

Tickets cost 3 florins per

person, for a gentleman

with a lady 5.50fl.

Admission cards will be

issued at Mr. Mozart's

present lodgings, at the

corner of Burgwal, just by

the City of Paris,

as well as at the Oude

Doelen.'

The 'overtures'

performed at the Dutch

concerts must have been

the London symphonies

discussed above, and the

Bb symphony, K. 22,

written in The Hague in

December 1765. These works

received further

performances on the

journey homeward to

Salzburg. We have more or

less certain evidence of

symphonies being performed

in Paris (sometime between

11 May and 8 July

1766), Dijon (18 July),

Lyons (13 August),

Lausanne (mid-September),

Zurich (7 and 9 October),

Donaueschingen (between 20

and 31 October), and

finally Salzburg itself

where, on 8 December, just

over a week after the

Mozarts’ triumphal return,

'at High Mass in the

Cathedral for a great

festivity [The Feast of

the Immaculate Conception],

a symphony was done which

not only found great

approbation from all the

Court musicians, but also

caused

greatastonishment...'.

A list of the

orchestral personnel of

the Schouwburg Theatre in

Amsterdam survives for the

year 1768. The orchestra

consisted of 3 first and 3

second violinists, 2

violists (both of whom

doubled on clarinet), 1

cellist, 1 bass player, 2

oboists (most likely

doubling on flute), 1

bassoonist, 2 horn

players, 1 harpsichordist,

and a supernumerary

who played kettledrums

when needed - thus a total

of 16 or 17 musicians. We

have modelled our

performance of Mozart's

two Dutch works on this

ensemble.

Symphony in Bb major,

K.22

At the top of Leopold

Mozart’s score of this

work, to be formd in the

State Library, West

Berlin, is the inscription

'Synfonia

di Wolfg. Mozart à

la Haye nel mese Decembre

1765.'

Despite the suggestion by

several of Mozart's

biographers, it is

unlikely that it was

written for the

installation of William V

as Regent of the

Netherlands, an event

which occurred some three

months later (see the

notes for the following

work). Rather, its

creation was probably

connected with public

perfonnances at The Hague:

the Mozarts’ concert there

on 30 September must have

shown off the London

symphonies, and its

success led in tum to the

concert of 22 January,

for which new music would

have been required.

The opening allegro in

common time is without

repeats. It begins with a

pedal in the bass for

fourteen bars, in a manner

associated with the

Mannheim symphonists but

heard in many parts of

western Europe by 1765.

The contrasting second

subject consists of a

dialogue between the first

and second violins,

followed by the apparently

mandatory theme in the

bass instruments

accompanied by tremolo in

the upper strings. A brief

but effective development

section puts the opening

idea through the keys of F

minor and C minor,

returning to the home key

shortly after the

reappearance of the second

subject, with the rest of

the exposition then heard

essentially as before.

The G-minor

andante, 2/4, exhibits

stuprising intensity of

musical gesture, with its

brooding chromaticism,

imitative textures, and

occasional stem unisons.

Abert thought that he

heard foreshadowings here

of the andante of Mozart’s

penultimate symphony, K.

550. The movement's form

is a simple A-B-A

structure with coda.

As if such intensity of

feeling were 'dangerous'

in a work intended for

polite society, the rondo

finale makes amends by

leaning in the other

direction. No tension mars

its frothy

lightheartedness. Marked

allegro molto, 3/8, it has

the spirit of a brisk

minuet, its opening

bringing to mind that of

the quartet 'Signore,

di fuori son già i

suonatori'

in the finale to the

second act of Figaro.

In Leopold’s travel diary

he noted two Amsterdam

musicians named Kreusser.

Johann

Adam Kreusser had been

leader of the Schouwburg

orchestra since 1752, and

his younger brother Georg

Anton had, from 1759,

taken lessons with him

while playing in that

ensemble. The latter must

have heard Mozart's

Bb-major symphony, K. 22

(probably as a member of

the orchestra that performed

it), because he paid it

the compliment of stealing

the opening of its first

movement for his own

Eb-major symphony, op. 5,

no. 4, published in

Amsterdam in 1770.

Symphony in D major,

K.32

For celebrations connected

with the installation of

William V, Prince of

Orange, as Regent of the

Netherlands, the

ten-year-old Mozart

composed a suite of pieces

for small orchestra and

obbligato harpsichord,

under the title Galimathias

musicum, which was

performed on 11 March

1766. This was a 'quodlibet';

that is, some movements

were based on tunes

well-known to Mozart and

his Salzburg compatriots,

and others on tunes

familiar to his Dutch

audience. The work

survives in two versions:

a preliminary draft in

which Wolfgang’s and

Leopold’s hands are found

intermingled, and a fair

copy apparently made by a

professional copyist for a

perfonnance in

Donaueschingen some months

later. From the draft

version it seems that

Mozart originally thought

of the first four

movements as forming a

kind of miniature

introductory sinfonia,

and these movements are

indeed found together in a

19th-century manuscript

labelled 'sinfonia.' (In

the Donaueschingen version

the order

of the movements

has been altered, however,

and the introductory sinfonia

dispersed. It is the four

movements of the

preliminary draft that are

presented here.

The opening allegro in

common time is nothing

more than a few happy

noises - repeated notes,

loud chords, rapid scale

passages, etc. - here

played twice. The D-minor

andante in binary form is

strangely orchestrated,

with the melody in the

violas.

For a minuet, there is a

G-major piece in which,

over a rustic drone, is

heard the melody of the

popular German Christmas

carol, 'Joseph,

lieber Joseph

mein'

(also known to Latin

words: 'Resonet

in laudibus'). The melody

is presented in a

particular version - not

the one usually found in

hymn books, but one known

to every denizen of

Salzburg because it was

played in the appropriate

season by a mechanical

carillon in the tower of

the Hohensalzburg Castle

that dominated (and still

dominates) that city.

(There also exists an

18th-century Salzburg

arrangement for wind band

of this version of the

carol, and Leopold Mozart

himself published an

arrangement of it for

harpsichord. Wolfgang

retumed to it in 1772,

quoting it in the original

slow movement of his

symphony, K. 132.) This

movement was suppressed in

the Donaueschingen

manuscript. The

contrasting D-major trio

takes the form of an

attractive horn duet with

merely a bass-line

accompaniment.

The 2/4

allegro finale offers us

another bright noise, to

close as we began. It is a

tiny,

two-part movement, with

lively, al fresco hom

duets at the beginning of

the second section.

····················

Performance

Practice

The use of

18th-century instruments

with the proper techniques

of playing them gives to

the Academy of Ancient

Music a vibrant,

articulate sound. Inner

voices are clearly audible

without obscuring the

principal melodies. Subtle

differences in

articulation are more

distinct than can usually

be heard with modern

instrtunents. At lively

tempos and with this

luminous timbre, the

observance of all of

Mozart's repeats no longer

makes movements seem too

long, and restores them to

their just proportions. A

special instance concems

the da capos of the

minuets, where, oral

tradition tells us, the

repeats should be omitted.

But, as we were unable to

trace that tradition as

far back as Mozart's time,

we experimented by

observing those repeats as

well. Missing

instruments understood in

18th-century practice to

be required have been

supplied: these include

bassoons playing the bass

line along with the cellos

and double basses,

kettledrums whenever

trumpets are present, and

the harpsichord continuo.

No conductor is needed, as

the direction of the

orchestra is divided in

true 18th-century fashion

between the concertmaster

and the continuo player,

who are placed so that

they can see each other

and are visible to the

rest of the orchestra. As

there was wide variation

in orchestral practice

from region to region in

western Europe, no

allpurpose classical

orchestra could be

recreated; consequently,

we have attempted to

present the several kinds

of ensembles for which

Mozart wrote, whose

peculiarities he had in

mind when composing.

Musical Sources and

Editions

Until recently performers

of Mozart’s symphonies

have relied solely upon

editions drawn from the

old Complete Works,

published in the 19th

century by the Leipzig

firm of Breitkopf & Härtel.

During the past three

decades, however, a new

complete edition of

Mozart’s works (NMA)

has been appearing,

published by Bärenreiter

of Kassel under the aegis

of

the Mozarteum of Salzburg.

The NMA has been

used for those works for

which it was available

(in this volume: K. 19a,

32, 74a/87, and the

overture to K. 111). For

the other symphonies,

editions have been

created especially for

these recordings,

drawing on Mozart's

autographs when they

could be sen, and on

other 18th-century

manuscripts in cases

where the autographs

were unavailable.

A Note

Concerning the Numbering

of Mozart's Symphonies

The first

edition of Ludwig Ritter

von Köchel's

Chronological-Thematic

Catalogue of the

Complete Works of

Wolfgang Amaadé

Mozart was published

in 1862 (=K1).

It

listed all of the

completed works of Mozart

known to Köchel

in what he believed to be

their chronological order,

from number 1 (infant

harpsichord work) to 626

(the Requiem). The second

edition by Paul Graf von

Waldersee in 1905 involved

primarily minor

corrections and

clarifications. A

thoroughgoing revision

came first with Alfred

Einstein's third edition,

published

in 1936 (=K3).

(A reprint of this edition

with a sizeable supplement

of further corrections and

additions was published in

1946 and is sometimes

referred to as K3a.)

Einstein changed the

position of many works in

Köchel's

chronology, threw out as

spurious some works Köchel

had taken to be authentic,

and inserted as authentic

some works Köchel

believed spurious or did

not know about. He also

inserted into the

chronological scheme

incomplete works,

sketches, and works known

to have existed but now

lost. These Köchel

had placed in an appendix

(=Anhang,

abbreviated Anh.)

without chronological

order. Köchel's

original numbers could not

be changed, for they

formed the basis of

cataloguing for thousands

of publishers, libraries,

and reference works.

Therefore, the new numbers

were inserted in

chronological order

between the old ones by

adding lower-case letters.

The so-called fourth and

fifth editions were

nothing more than

unchanged reprints of the

1936 edition, without the

1946 supplement. The sixth

edition, which appeared in

1964 and was edited by

Franz Giegling, Alexander

Weinmann, and Gerd Sievers

(=K6),

continued Einstein's

innovations by adding

numbers with lower-case

letters appended, and a

few with upper-case

letters in instances in

which a work had to be

inserted into the

chronology between two of

Einstein's lowercase

insertions. (A so-called

seventh edition is an

unchanged reprint of the

sixth). Hence, many of

Mozart's works bear two K

numbers, and a few have

three.

Although it was not Köchel's

intention in devising his

catalogue, Mozart's age at

the time of composition of

a work may be calculated

with some degree of

accuracy from the K

number. (This works,

however, only for numbers

over 100). This is done by

dividing the number by 25

and adding 10. Then, if

one keeps in mind that

Mozart was born in 1756,

the year of composition is

also readily approximated.

The old Complete Works of

Mozart published 41

symphonies in 3 volumes

between 1879 and 1882,

numbered 1 to 41 according

to the chronology of K1.

Additional symphonies

appeared in supplementary

volumes and are sometimes

numbered 42 to 50,

even though they are early

works.

Bibiography

- Abert,

Anna Amalie: 'W.

A. Mozart, Sinfonie KV 84 =

73q. Echtheitsfragen,'

Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1971-72)

- Allroggen,

Gerhard: 'Zur Frage

der Echtheit derSinfonie

KV. Anh. 216 = 74g,'

Analecta musicologica

(1976), xviii

- Anderson,

Emily: The Letters

of Mozart & His Family,

2nd ed. (London, 1966)

- Anon., 'Wiederauffindung

einer verschollenen

Jugendsinfonie

Mozarts durch die

Bayerische

Staatsbibliothek,'

Acta

Mozartiana

(1981), xxviii/1

- Barblan,

Guglielmo, et al.: Mozart

in Italia

(Milan 1956)

- Beck,

Hermann: 'Zur Frage

der Echtheit vonMozarts

Sinfonie in D, KV

84/73q,'

Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1972-73)

- Della

Croce, Luigi: Le

75 sinfonie de

Mozart (Turin,1979)

- Deutsch,

Otto Erich: Mozart:

A DocumentaryBiography,

2nd ed. (London, 1966)

- Eibl, Joseph

Heinz, et al.:

Mozart: Briefe und

Aufzeichnungen

(Kassel, 1962-75)

- Framery,

Nicolas Etienne: 'Quelques

réflexions

sur la musique

rnoderne,' Journal

de musique

historique, théorique,

et pratique

(May 1770)

- Galeazzi,

Francesco: Elementi

teorico-pratici di musica

con un saggio sopra

l'arte di suonare il

violono (Rome,

1791-96)

- LaRue, Jan:

'Mozart or Dittersdorf

- KV 84/73q,'

Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1971-72)

- Mila,

Massimo: Le

Sinfonie de Mozart (Turin,

1967)

- Saint-Foix,

Georges de: Les

Symphonies de Mozart

(Paris, 1932)

- Scheurleer,

Daniel François:

Het Muziekleven in Nederland

in de tweede helft

der 18e eeuw in verband met

Mozart's verblijf

aldaar (The

Hague, 1909)

- Schmid,

Ernst Fritz: 'Zur

Entstehungszeit von

Mozarts

italienischen

Sinfonien', Mozart-Jahrbuch

(1958)

- Schultz,

Detlef; Mozarts Jugendsinfonien

(Leipzig,

1900)

- Terry,

Charles Sanford: John

Christian Bach,

2nd

ed. by H. C.

Robbins Landon

(London, 1967)

- Wallner,

Bertha Antonia: 'Ein

Beitrag zu Mozarts

Londoner

Sinfonien,' Zeitschrift

für

Musikwissenschaft

(1929-30), xii

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'The Compleat

Orchestral

Musician,'

Early Music

(1979), vii/1

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'Mozart,

Haydn and the Sinfonia da

chiesa,' Journal

of Musicology (January

1982), i

- Zaslaw,

Neal: 'Toward the

Revival of the

Classical Orchestra,'

Proceedings of the

Royal Musical

Association

(1976-77), ciii

|

|

The Italian

Symphonies

Mozart's youth in

Salzburg was punctuated

by three journeys to

Italy, which lasted from

13 December 1769 to 28

March 1771, 13 August

1771 to 15 December

1771, and 24 October

1772 to 13 March 1773.

Thus during the period

from just before

Mozart's fourteenth

birthday until shortly

after his seventeenth,

he spent a total of

about twenty-two months

in the land that many of

his contemporaries

considered the fount of

modern music. In so

doing, Mozart and his

father were following a

well-beaten path, for

generations of German

composers had served

apprenticeships in

Italy, including Handel,

J.

C. Bach, Hasse and

Gluck. The primary goal

of such journeys was

usually mastery of

Italian opera, but

training in other

musical genres was not

neglected. This was the

situation discussed in

an essay of 1770 by

Nicolas Etienne Framery

entitled 'Some

Reflexions upon Modern

Music,' from which the

following fragments are

taken:

'While the French and

the Italians were

disputing which of them

possessed music, the

Germans learned it,

going to Italy for that

purpose... The German

artists filled the

public conservatories of

Naples... They had all

the raw materials

required of great

musicians; they lacked

only the discipline to

organise those

materials, and they had

no trouble acquiring

that... Upon leaving the

schools, the Italian

pupils remain in their

own country... The

Germans, on the

contrary, return to

their country. They have

carefully preserved

their prodigious

accumulation of [musical]

science. They have

tested the very

fortunate use of wind

instruments of which

their nation makes much

use, and they have known

how to draw the most

from them... They have

realized that all

expression does not suit

vocal melody; that there

are a thousand nuances

which the orchestra is

much more fit to render

[than the voice]. They

have tried,

they have succeeded, and

have raised themselves

far above their masters,

who now rush to imitate

them...'.

From the letters that

Mozart and his father

wrote home during these

travels (for Mozart's

mother and sister

remained in Salzburg),

we learn that they had

need of symphonies for

public and private

music-making, that they

brought some symphonies

with them from Salzburg,

and that Wolfgang

composed others while in

Italy.

The first such concert -

which took place in

Verona on Friday, 5 January

1770, in the Teatrino

della Accademia

Filarmonica - was

probably typical of many

of them. Leopold

described the occasion

in a letter to his wife:

'In

all my life I have never

seen anything more

beautiful of its kind...

It is not a

theatre, but a hall

built with boxes like an

opera house. Where the

stage ought to be, there

is a raised platform for

the orchestra and behind

the orchestra another

gallery built with boxes

for the audience. The

crowds, the general

shouting, clapping,

noisy enthusiasm and

cries of "Bravo!"

and, in a word, the

admiration displayed by

the listeners, I cannot

adequately describe to

you.'

A newspaper account

confirms the enthusiasm

with which Wolfgang was

received, mentioning 'a

most beautiful

introductory symphony of

his own composition,

which deserved all its

applause.' A similar

programme given in

Mantua at the Teatro

Scientifico on 16 January

1770, to acclaim equal

to that received in

Verona, demonstrates the

characteristic function

usually assigned

symphonies in concerts

of the second half of

the 18th-century, that

of 'framing' the event:

1. First and second

movements of a symphony

by Mozart

2. Harpsichord concerto

played at sight by

Mozart

3. Aria sung by the

tenor Uttini

4. Harpsichord sonata

played at sight and

omamented by Mozart, and

then repeated in a

different key

5. Violin concerto by a

local virtuoso

6. Aria improvised by

Mozart upon a poem

handed him on the spot,

sung by him to his own

harpsicord accompaniment

7. Two-movement

harpsichord sonata

improvised by Mozart on

two themes given him on

the spot by the

concertmaster; at the

end the two themes were

'elegantly' combined

8. Aria sung by the

soprano Angiola Galliani

9. Oboe concerto by a

local virtuoso

10. Harpsichord fugue

improvised by Mozart on

a theme given him on the

spot

11. Symphony accompanied

by Mozart on the

harpsichord from a first

violin part given him on

the spot

12. Duet by two

professional musicians

13. Trio 'by a famous

composer'

in which Mozart

performed at sight the

first violin part,

ornamenting it

14. Finale of the

opening symphony.

As for his fellow

musicians in Mantua,

Wolfgang wrote in a

letter, 'The

orchestra was not bad.'

The only drawback to

these otherwise

brilliant events was

explained by Leopold to

his wife:

'...neither

this concert in Mantua

nor the one in Verona

were given for money,

for everybody goes in

free; in Verona this

privilege belongs only

to the nobles who alone

keep up these concerts;

but in Mantua the

nobles, the military

class and the eminent

citizens may all attend

them, as they are

subsidised by Her

Majesty the Empress. You

will easily understand

that we shall not become

rich in Italy...'.

The symphonies played at

Verona and Mantua must

have been brought from

Salzburg. The first hint

of symphonies composed

in Italy is found in

Wolfgang’s letter of 25

April 1770, written from

Rome to his sister:

'When I have finished

this letter I shall

finish a symphony which

I have begun... A

symphony is being copied

(father is the copyist,

for we do not wish to

give it out to be

copied, as it would be

stolen).' On 4 August,

writing from Bologna in

another letter to his

sister, Mozart remarked,

'In the meantime I have

composed 4 Italian

symphonies...'. This

expression 'Italian

symphonies'

has usually been taken

to mean three-movement

symphonies, that is to

say, symphonies without

the minuet and trio

characteristic of the

so-called Viennese

symphony of the period.

Hence it has frequently

been asserted,

concerning those of

Mozart's symphonies

thought to originate in

Italy which do have

minuets, that the latter

must have been added

later for use in

Salzburg. But Mozart

wrote to his sister of

his desire to introduce

to Italy minuets in the

German manner because,

according to him,

Italian minuets 'last

nearly as long as an

entire symphony' and

'have many notes, a slow

tempo, and are many bars

long.' By 'Italian

symphonies,' therefore,

Mozart may simply have

meant symphonies written

in and for Italy,

without reference to the

presence or absence of

minuets.

Two symphonies (K. 73l/81

and 73q/84) exist in

sets of non-autograph

parts in Vienna with

indications of their

provenance. The parts

for the former symphony

are labelled 'in Roma

25. April 1770.' The

parts for the latter

bear the inscription at

the top 'In Milano, il

Carnovale 1770,' but at

the bottom this is

contradicted by another

inscription: 'Del

Sig[no]re Cavaliero

Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart

à

Bologna, nel mese di

Luglio 1770.'

Nevertheless, the two

symphonies written in

Rome in April are

probably K. 73l/81

and 73q/84, and the four

symphonies mentioned in

Bologna in August most

likely include those two

works plus two others,

the identity of which is

unclear.

For five other

symphonies which may

date from Mozart's

Italian journeys,

neither autographs

nor other 'authentic'

sources survive K.

73m/97,73n/95,

74g/AC11.03/A216, 75 and

111b/96). These have

been given their

chronological positions

in the Köchel

Catalogue on imprecise

stylistic grounds and,

in fact, cannot even be

proven to be by Mozart.

Problems of attribution

are severe among the

symphonies of this

period. Four symphonies

have attributions to

both Leopold and

Wolfgang in various

sources (K. 73l/81,

73m/97, 73n/95, and

73q/84), and the last of

these is attributed also

to Dittersdorf.

Of Mozart's eleven

Italian symphonies,

eight are in D major. A

clue as to why this is

so may be contained in a

cryptic remark Mozart

made to his father in

1782 about his 'Haffner'

symphony: 'I have

composed my symphony in

D major, because you

prefer that key.'

This may be because D

major is simultaneously

a brilliant yet easy key

for string players,

which, unlike the other

'easy' keys (G and A

major) is also one of

the trumpet

keys, permitting

the addition of those

instruments whenever

they were available. It

remains only to add that

Mozart's D major

symphonies of the 1770s

seem more conventional

and less personal

in character than

several of those he

wrote in other keys.

The most famous Italian

orchestras in the early

1770s were those of the

opera houses of Turin,

Milan and Naples. We

have pictures of the

Turin orchestra in

performance, as well as

seating diagrams of the

Turin and Naples

orchestras. The players

sat facing one another

in long rows, half

toward the audience and

half toward the stage.

Leopold wrote in

December 1770 that the

Milan orchestra

consisted of 28 violins,

6 violas, 2 cellos, 6

double basses, 2 flutes

who doubled on oboe, 2

oboes, 2 bassoons,

4 horns, 2 trumpets,

kettledrums, and 2

harpsichords. How such

orchestras rearranged

themselves when

performing concerts

rather than operas was

described by Galeazzi

(1791):

'The best placement for

good effect is to

arrange the players in

the middle of the hall

with the audience all

around them; but the

visual impression is

more satisfying if you

arrange them to one

side, against one of the

walls of the

drawing-room (supposing

a rectangular-shaped

area), because the

audience thus enjoys the

entire orchestra from

the front. The violins

are then placed in two

rows, one opposite the

other so that the firsts

are looking at the

seconds... With regard

to the bass-line

insuuments, if there are

only two, place them

near the harpsichord (if

there is one) in such a

way that the violoncello

remains near the leader

of the first violins and

the double bass on the

opposite side, and between

them the maestro or

harpsichordist; but if

there are more bass-line

instruments, and if they

are played by good

professional musicians,

place them at the foot-

that is, at the other

extremity - of the

orchestra, otherwise you

should place them as

near to the firsts as

you possibly can. The

violas are always best

near the second violins,

with whom they must

often unite in thirds,

in sixths, etc., and the

oboes are best alongside

the firsts. The brass

can then be placed not

far from the leader. In

this disposition all the

heads of sections -

namely, the leader, the

principal second violin,

the principal cello, the

maestro, the singers,

etc. - are neighbours,

by which means perfect

ensemble cannot but

result.

For smaller orchestras,

a semi-circular

arrangement of the

players was also

employed. A

passe-partout title page

used by the Florentine

publisher Giovanni

Chiari in the 1780s

shows this particular

orchestral layout. The

orchestra is rehearsing

either on a stage with

sets representing a

formal garden, or in an

actual garden with

topiary trees. On the

left, from front to

back, we see 2 horns,

4 first violins, the

first oboe, and the

first viola; on the

right 2 trumpets

(showing plainly why

Mozart designated them

'trombe lunghe' in his

scores), 4 second

violins, the second

oboe, and the second

viola. In the centre at

the back we see the maestro

al cembalo,

surrounded by a cello, a

double bass and a singer

of each sex. Another man

seems to be directing

the rehearsal, while

fashionably attired

ladies and gentlemen

stroll, chat or listen,

a dog barks and someone

sweeps up.

For these performances

we have applied

Galeazzi's instructions

to the personnel lists

of Turin, Milan and

Naples for the

large-scale symphonies

(those with trumpets and

kettledrums), and

followed the Chiari

engraving for the

smallscale ones (those

without these festive

instruments). The

large-scale orchestra

has the strings at

12-12-4-2-6, five

bassoons (reinforcing

the bass line), the

necessary wind, and two

harpsichords improvising

a continuo. The great

strength of the violins

and double basses and

the relative weakness of

the violas and cellos

creates a sound quite

distinct from that of

the London, Paris,

Salzburg, or Vienna

orchestras, also

recreated in this series

of recordings. The

predominance of the

double basses over the

cellos creates an

organ-like sonority that

makes the acoustic of a

theatre or hall resemble

that of a cathedral. The

timbre is more

'archaic,' that is, it

tends toward the Baroque

ideal and away from the

Classical. The strong

contingent of bassoons

compensates for the

small number of cellos

and etches the details

of the bass line with

scintillating clarity.

For the small-scale

orchestra, the strings

are 6-5-2-2-1 (following

further advice from

Galeazzi about proper

string balance), with

one bassoon, the

necessary wind and one

harpsichord. The layout

in the Chiari engraving

emphasizes a special

feature of the

orchestration of

Mozart's Italian

symphonies: the first

oboe often doubles the

violin in unison or the

first viola in octaves,

while, in a similar

fashion, the second oboe

often doubles the second

violin or the second

viola.

Symphony in D major,

K.73l/81

As we have seen, a

manuscript copy of this

work dated Rome, 25

April 1770 attributes it

to Wolfgang, but in a

Breitkopf thematic

catalogue published in

1775 it is listed as a

work of Leopold’s. The

symphony - bright,

superficial and

conventional - has

generally been accepted,

however, as being by

Wolfgang. The orchestra

is small: pairs of oboes

and horns, strings, and

harpsichord continuo.

The first movement opens

with a rising D-major

arpeggio, an idea that

is turned upside down

for the opening of the

finale. It continues as

a compactly organized

sonata form without

repeats, and with a

literal recapitulation.

The tiny 'development'

section of twelve bars

could perhaps more aptly

be called a transition.

The second movement, a

G-major andante in 2/4,

features a dialogue

between the first and

second violins, the

conversation soon

broadening to include

the pair of oboes. In

this serene binary

movement with both

halves repeated Wyzewa

and Saint-Foix detected

the influence of the

Milanese composer

Giovanni Battista Sammartini.

The 3/8 finale,

marked allegro molto, is

the sort of movement

known as a 'chasse' or

'caccia' - that is, a

jig filled with

hunting-horn calls. This

'hunt' would seem to be

one contemplated from

the comfort of the

drawing room, however,

far from the mud and

commotion of the actual

event. The form is a

binary arrangement as

described for the first

movement of K. 19a.

Symphony in D major,

K.73m/97

This work survived in a

single undated,

nonautograph manuscript

in the archive of

Breitkopf & Härtel

in Leipzig. Its

provenance is therefore

completely unknown. In

recent editions of the Köchel

catalogue it has been

assigned to Rome, April

1770, on largely

illogical grounds. It

has nonetheless been

included here among

Mozart's Italian

symphonies, for lack of

a better hypothesis.

The first movement is an

Italian overture in

style and spirit, in

sonata form with no

repeated sections. The

trumpets add to the

festivity, as well as

helping to outline the

movement’s structure. A

neatly-worked-out, brief

development section

travels through G major,

E minor and B minor,

before re-establishing

the home key.

The andante, a binary

movement in G major 2/4,

with both halves

repeated, exhibits an

attractive mock-naïveté.

The minuet that follows

adheres to Mozart's

preference (documented

above) for brevity. In

fact, the spirit of the

movement is more of the

ballroom than the

symphony. The G-major

trio omits the wind and,

by its chamber-music

character, provides an

excellent foil to the

pomp of the minuet

proper.

The finale is a gem. It

is a jig-like movement

(presto, 3/8) in sonata

form, with a brief but

effective development

section. Furthermore,

the movement contains an

uncanny adumbration of a

passage in the first

movement of Beethoven's

Seventh Symphony, not

only in the theme itself

but in the way in which

it is immediately

repeated with a turn

to the minor. Beethoven

cannot have known this

work, so we can only

speculate about

coincidence or an

as-yet-undiscovered

common model.

Symphony in D major,

K.73n/95

The source for this work

is identical to that of

the previous one, and

doubts about its

provenance are equally

severe. It has been

given the same place and

date as the previous

symphony on similarly

unsatisfactory grounds,

and is included here for

the same reason.

The first allegro, alla

breve, opens with an

idea more or less the

same as that which

launches the symphonies

K. 73m/97 and 74. It is

in sonata form without

repeats. The movement is

an essay in orchestral

'noises' put together to

form a coherent whole.

That is, there are no

memorable, cantabile

melodies, but rather a

succession of idiomatic

instrumental

devices, including

repeated notes, scales,

fanfares, turns,

arpeggios, sudden

dynamic changes, etc.

Descriptions and

explanations of musical

form tend to fall back

on linguistic analogies.

In

this case, however, such

an analogy would lead us

into the absurd position

of having to imagine

meaningful prose

composed of articles,

conjunctions and

prepositions! Responding

to this paradox, Schultz

refers to such movements

as 'purely decorative.'

Leopold Mozart once

called a symphony of J.

Stamitz in this vein

'nothing but noise.' The

18th-century

aesthetician Lacépéde

thought that, therefore,

symphony movements

needed programmes to

make sense of otherwise

'meaningless' musical

events. These reactions,

and the failure of the

linguistic analogy,

point to a weakness of

aesthetic theory in

dealing with an art of

abstract sounds

unsupported by

association with

concretre verbal ideas.

(A parallel may be drawn

with the difficulties

surrounding the

acceptance of

non-representational

painting in the 20th

century.)

The first movement comes

to a halt on a D-major

chord with an added

seventh, leading

directly into the

G-major 3/4 andante.

Whatever lyricism may

have been lacking in the

previous movement is

more than atoned for in

its songful successor.

The trumpets and

kettledrums drop out and

the oboes are replaced

by flutes, which lend a

pensive, pastoral hue to

this sweet-sounding

interlude.

The oboes and trumpets

return for the

boisterous minuet, in

which Mozart presents

yet another example of

concision for the

instruction of his

longer-winded Italian

colleagues. The trio in

D minor omits the trumpets,

and with its quiet

intimacy nicely sets off

the retum of the minuet.

The allegro 2/4 finale

returns us

to the sonata fomi and

happy noises of the

opening movement. The

two movements are even

linked by the same

opening gesture.

Symphony in D major,

K.73q/ 84

This symphony survives

in manuscripts in Vienna

(attributed to

Wolfgang), Berlin

(attributed to Leopold),

and Prague (attributed

to Dittersdorf). A close

stylistic analysis of

the work by LaRue has

shown that Wolfgang is

the most likely of the

three to have been the

composer. As has already

been mentioned, the

Vienna manuscript bears

two inscriptions: 'In

Milani, il Carnovale

1770' and 'Del Sig[no]re

Cavaliero Wolfgango

Amadeo Mozart a Bologna,

nel mese di Luglio 1770.'

These apparently

contradictory bits of

information may perhaps

be resolved in the

following manner: in

1770 Carnival lasted

from 6 January

until 27 February, and

the Mozarts were in

Milan from 23 January

to 15 March, and in

Bologna from 20 July

to 13 October. Hence, if

the inscriptions are to

be trusted, this

symphony may well have

been drafted in Milan in

January

or February and have

received its final

revision in Bologna in July.

The opening allegro in

common time exhibits a

fully-fledged sonata

form without repeated

sections. There are,

well differentiated, an

opening group of ideas,

a second group and a

closing group, a brief

development section of

eleven bars, and a full

recapitulation.

The 3/8 andante in A