|

1 CD -

Teldec 8.42955 XH (c) 1989

|

|

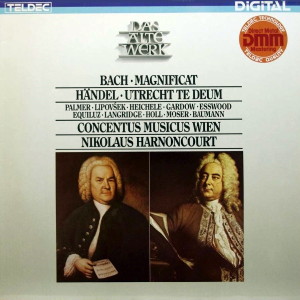

| 1 LP -

Tedec 6.42955 AZ (p) 1984 |

|

| NIKOLAUS HARNONCOURT - 25 Years

on TELDEC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Johann Sebastian

Bach (1685-1750) |

Magnificat D-dur,

BWV 243 |

|

27' 39" |

A |

|

-

Magnificat |

4' 18"

|

|

|

|

- Et exsultavit spiritus meus |

2' 40"

|

|

|

|

- Quia

respexit humilitatem |

2' 01"

|

|

|

|

- Omnes

generationes |

1' 26"

|

|

|

|

- Quia

fecit mihi magna |

1' 58"

|

|

|

|

- Et misericordia |

3' 33"

|

|

|

|

- Fecit

potentiam |

1' 59"

|

|

|

|

-

Deposuit potentes |

2' 08"

|

|

|

|

-

Esurientes implevit bonis |

2' 56"

|

|

|

|

-

Suscepit Israel |

1' 24"

|

|

|

|

- Sicut locutus est |

1' 34"

|

|

|

|

-

Gloria Patri |

2' 15"

|

|

|

| Georg Friedrich

Händel (1685-1759) |

Utrechter Te Deum, HWV

278 |

|

24' 28" |

B |

|

-

Chorus: Adagio-Allegro "We praise

Thee, O God" |

2' 28"

|

|

|

|

-

Chorus: (Allegro) "All the earth

doth woorship Thee" |

1' 47"

|

|

|

|

- Soli

and Chorus: (Largo) "To Thee all

angels ery aloud" |

1' 04" |

|

|

|

- Soli

and Chorus: Andante "To Thee

Cherubin ans Seraphin" |

1' 11" |

|

|

|

- Soli

and Chorus: (Allegro)-Adagio "The

glorious company" |

3' 22" |

|

|

|

-

Chorus: Allegro - Adagio-Allegro "Thou

art the King of Glory" |

2' 01" |

|

|

|

- Soli

and Chorus: Adagio-Allegro-Adagio "When

Thou took'st upon Thee"... "When

Thou hadst overcome" |

2' 45" |

|

|

|

-

Chorus: Allegro "Thou sittest at the

right hand of God" |

1' 09" |

|

|

|

- Soli

and Chorus: Adagio "We believe that

Thou shalt come" |

2' 45" |

|

|

|

-

Chorus: (Allegro) "Day by day we

magnify Thee" |

1' 19" |

|

|

|

-

Chorus: (Allegro) "And we worship

Thy Name" |

0' 51" |

|

|

|

- Soli

and Chorus: (Andante) "Vouchsafe, O

Lord" |

2' 44" |

|

|

|

-

Chorus: (Allegro) "O Lord, in Thee

have I trusted" |

1' 02" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Magnificat |

Utrechter

Te Deum |

|

|

|

|

| Hildegard

Heichele, Soprano I |

Felicity

Palmer, Soprano |

|

| Helrun

Gardow, Soprano

II |

Marjana

Lipovsék, Alto |

|

| Paul

Esswood, Alto |

Philip

Langridge, Tenore |

|

| Kurt

Equiluz, Tenore |

Kurt

Equiluz, Tenore |

|

| Robert

Holl, Basso |

Thomas

Moser, Tenore |

|

| Wiener

Sängerknaben & Chorus Viennensis /

Uwe Harrer, Chorleitung |

Ludwig

Baumann, Basso |

|

| CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit Originainstrumenten) |

Arnold-Schönberg-Chor / Erwin Ortner, Chorleitung

|

|

| Nikolaus

HARNONCOURT, Leitung |

CONCENTUS MUSICUS

WIEN (mit Originainstrumenten) |

|

|

Nikolaus

HARNONCOURT, Leitung |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Casino

Zögernitz, Vienna (Austria):

- 25 maggio 1983 (Bach)

- 17 gennaio 1984 (Händel) |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer

|

|

- |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

TELDEC

- 8.42955 XH (242 984-2) - (1 CD -

durata 58' 24") - (c) 1989 - DDD |

|

|

Originale LP

|

|

TELDEC

- 6.42955 AZ - (1 LP - durata 58'

24") - (p) 1984 - Digitale |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Magnificat D major

There are three

canticles from the Ncw

Testament in the Roman Catholic

liturgy: the Benedictus, the

Nunc dirnittis and the

Magnificat (My soul doth magnify

the Lord), the words spoken by

the Virgin Mary (Luke I,

46-55) in the house of Zacharias

when her cousin Elisabeth

greeted her as the mother ofthe

future Saviour. - Originally the

ten verses of the Magnificat and

the concluding “Gloria Patri”,

the lesser doxology, were sung

during Vespers in unison,

i. e. in plainsong. In the

Protestant Church in Germany

this Marian hymn, often sung in

German, was also the climax of

Evensong, but only on feast

days. Since the middle of the

15th century settings of the

Magnihcat in several parts have

increasingly been written and

appreciated. In analogy with the

antithesis between the burden of

original sin and the Saviour’s

promise, the musical exegesis

also deploys contrasting

movements.

Johann Sebastian Bach probably

composed the Magnificat in D,

BWV 243, around 1732/33. It is

usually referred to as the

“later” version,

the earlier one in E flat,

BWV 243 a, having probably been

sung at St. Thomas’, Leipzig, at

Christmas 1723. The autograph

scores of both versions are

preserved in the German State

Library, Berlin. In 1955

the new edition of Bach’s works

(Neue Bach-Ausgabe) for the

first time presented both

versions side by side, but

clearly distinct, and

accompanied by an extensive

critical commenmry by

A. Dürr. According to this,

the autograph of the D major

version (Mus. ms. Bach P39),

close in time to the Mass in B

minor, BWV 232, is “one of

Bach’s most beautiful fair

copies in our possession. Not

only do the staves, the bar

lines and the actual notes

indicate particular care in the

writing, but so do the

specification of the instruments

and expression marks, which in

less meticulously written

original manuscripts can

frequently only be discovered

from the parts.” The later, D

major, work has three distinct

advantages over the earlier, E

flat, version: its key makes it

much easier for the brass

instruments, with their limited

tuning and range, to play the

top notes, which

sometimes run on for

several bars. The scoring of the

work as a whole is distinguished

by being enlarged by two flutes.

Finally, on account of its

neutral character, the four

Christmas-orientated movements

interpolated in the E flat

version being eliminated, the D

major work can be performed all

the year round.

Unlike the ten verses of the

biblical text, the work consists

of twelve sections, since Bach

subdivided the first two verses

and added on the doxology. The

opening chorus “Magnificat” (D

major; 3/4 time) is framed by a

spacious instrumental ritornello

with a substantially shorter

repeat, the opening section

already presenting the melodic

material of the five-part

chorus. In accordance with the

festive character of the work,

three trumpets, supported by two

timpani, shine brightly out of

the instrumental tutti. - The

“Et exsultavit” (second soprano;

d major; 3/ 8 time), a binary

aria accompanied only by a

string trio and continuo,

creates a pronounced contrast.

The discreet semiquaver

coloratura also symbolises

rejoicing. - Bach employs

word-painting in the descending

melodic line, first played by

the gently sounding oboe

d’amore, for the next aria, the

predominantly syllabic "Quia

respexit” (first soprano; B

minor; common time) to portray

the lowliness of the chosen

handmaiden. - In the immediately

following five-part chorus

(F sharp minor) the lastwords of

verse 3 “Omnes generationes” are

brilliantly interpreted. - The

melody of the bass aria (A

major; common time) in verse 4

“Quia fecit mihi magna” is

played as a basso ostinato by

the continuo. Syllabic

treatment and coloratura

alternate regularly. - An

instrumental ritornello of four

bars determines the character of

the duet for alto and tenor of

verse 5 “Et misericordia” (E

minor; l2/8 time), praising

God’s mercy. The melodic line of

the first and second violins,

predominantly in parallel

thirds, and of the two flutes,

mostly in unison with the

violins, is matched by the

gently rocking rhythm; these

features serve to emphasise the

siciliano nature of the

movement. - The orchestration of

“Fecit potentiam" (D major;

common time) is the same as that

of the opening movement. The

wider intervals symbolise His

strength, while massive

descending octaves in the

ostinato bass suggest the

scattering of the proud

(“superbos mentes”) who are

realistically rebuked in the

dissonances of the concluding

homophonic adagio. - In

“Deposuit”, a tenor aria (F

sharp minor 3 /4 time)

accompanied solely by the

violins, the text is interpreted

not only by the choice of key

but also by the descending

melodic line, illustrating how

the mighty are put down from

their seats (“deposuit

potentes“), while the ascending

line represents the humble and

meek, whom He exalts (“exaltavit

humiles”). The wide

intervals once again symbolise

divine power. - The binary aria

“Esurientes” (E major; common

time) is another masterly

example of word painting: the

modest instrumentation with just

two flutes is matched by a

restrained melodic line, mostly

in conjunct motion. - In the

contrapuntal trio “Suscepit

Israel” (tirst and second

soprano, alto; B minor; 3/4

time) the oboes in unison play

the tune of the Magnilicat as a

cantus firmus in note values of

equal length. - The five-part

choral fugue “Sicut locutus est”

(D major; alla breve) symbolises

faith and confidence, - The

“Gloria Patri” (A major; common

time) is characterised both by

dotted chords and by ascending

chains of triplets, while

timpany and trumpets emphasise

the festive nature of the

doxology. A pause on an A maior

cadence is followed by the

concluding “Sicut erat” (D

major; 3/4 time) which is based

on the opening chorus.

Renate Federhofer-Königs

(Translation: Lindsay

Craig)

··········

Utrechter

Te Deum

The outcome of the War of

the Spanish Succession

(1701-1713/14) enabled

Britain to negotiate a

favourable settlement in the

Treaty of Utrecht, one of

the territories gained by

her at the expense of Spain

being Gibraltar. Victories

of that nature were

celebrated in church

services which frequently

culminated in a Te Deum. For

centuries this ancient hymn

of praise and thanksgiving

had been sung at Mass on

special occasions. Since the

16th century and more

specifically during the

baroque period specially

commissioned works, for all

that they were based on

Gregorian chant, were not

infrequently expressions of

political power rather than

religious fervour. Gun

salvoes and victory fanfares

were the rule, though Handel

employed none of these

special effects in any of

his five Te Deum

compositions. Arriving in

London for the second time

in l7l2, he rapidly made a

name for himself with his

operas “Il pastor fido”

and “Teseo”; he also

composed an “Ode for the

Birthday of Queen Anne” (6th

February 1713) in which the

monarch was celebrated as a

bringer of peace. This work

also refers to the Peace of

Utrecht. Handel must have

been commissioned for both

the Te Deum and

the Ode while

negotiations were still in

progress. Since the Te Deum

was finished on l4th January

1713, whereas the peace

negotiations were only

concluded at the end of

March of that year. The

Utrecht Te Deum laid the

foundation of Handel’s fame

in England and remained his

best-known work until the

“Messiah” (1742) and thc

Dettingen Te Deum (l743).

After the separation of the

Anglican from the Roman

Catholic church, the

liturgical Te Deum was, as

early as the middle third of

the 16th century, absorbed

and adapted both to its

religious attitudes and its

musical tradition. In the

Anglican church, the place

of the concertante masses

and psalms of

Catholicism and the

motets and cantatas of the

Lutheran faith is taken by

the anthem. This is clearly

derived from the motet and

the part song for several

soloists of the English

renaissance. In spite of the

use of

instrumental ensembles

there are no self-contained

solo movements as in Latin

or German church music.

While on the continent the

baroque Te Deum was modelled

on the cantata, in England

the “Festival Anthem” with

an ensemble of soloists

together with chorus and

orchestra became the

prototype for Te Deum

compositions, Henry Purcell

wrote one in 1694 for the

Feast of St. Cecilia (22nd

November), which was

subsequently performed every

year on that day in honour

of the patron saint of

music. This was the work

that Handel emulated for his

Utrccht Te Deum, his first

composition for the

Anglican church,

which from then on was

given preference over

Purcell’s. Like Purcell

Handel also wrote a

Jubilate to complement his

Te Deurn; after the peace

proclamation, on 5th

May 1713, both works were

performed at the peace

celebrations in St. Pauls’s

Cathedral on 7th July.

When one traces Handel’s

development one mervels to

observe how qickly he was

able to turn new musical

impressions and stimuli into

works ofhis own. During his

travels in Italy he

encountered

the Italian oratorio,

which resulted in

his first work of that

type, “La resurrezione”

(Rome, 1708), an oratorio in

the Italian style for solo

voices and orchestra with

magniticant solo parts.

In London

he immediately struck

gold with his Utrecht Te

Deum in the spirit of the

Anglican church, without

quite abandoning the German

tradition or the impressions

gained in Italy. Handel was

a man of the world in the

true sense of the term, a

cosmopolitan of the music of

his day.

The Utrecht Te Deum is

scored for five

soloists, live-part chorus

and a brilliant orchestra

including timpani and

trumpets. It is divided

into seven main sections

(with 14 subdivisions) which

are arranged with a

sensitive appreciation of

tonal shading and attention

to musical diversity. The

trequent alternation of

homophonic and polyphonic

sections is as typically

English as is the contrast

between the ensemble of

soloists and the chorus,

fore example in the

magnificent “We believe that

Thou shalt come” and the

“and we worship Thy name”,

in which the trumpets lead

the orchestra. The use

of musical figures to

interpret the text, such as

in the opening chorus and

the immediately following

contrasting double fugue to

the words “All the earth

doth worship Thee”, arising

from the depths, together

with homophonic interludes,

combines German and English

traditions. The doubled alto

(countertenor) parts are

also typically English. The

Italian Concerto grosso,

translated into vocal music,

is apparent in the praise of

the angels, in which Handel

followed Purcell’s example

by using word painting for

the word “cry”. One

particular feature of this

work is the mounting tension

in the section “The glorious

company ofthe

Apostles". The prelude,

which opens with two oboes,

introduces an expansive

coloratura passage for the

tenor, followed by a bass

solo with oboe imitation and

a duet for two sopranos

leading to the homophonic

chorus “The holy Church”.

The musical treatment of the

English text (e. g. in “Thou

sittest”) proves Handel’s

intense preoccupation with

his task. "Thou

art the King of

Glory" is set to the Tc

Deum tune, and the final

chorus to a Gregorian Amen.

Both were transformed by

Handel in such a manner taht

they now resemble one

another and give the

impression of being his own

thematic material.

Gerhard

Schuhmacher

(Translation: Lindsay

Craig)

|

|