|

|

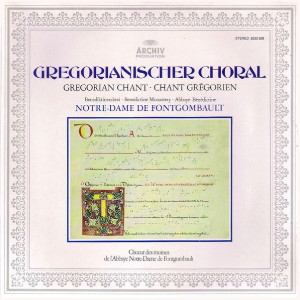

1 LP -

2533 359 - (p) 1978

|

|

| 4 CD's -

435 032-2 - (c) 1993 |

|

| THE TRADITION OF

THE GREGORIAN CHANT - (VI) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTRE-DAME

DE FONTGOMBAULT - Benedictine

Monastery

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AD

MISSAM |

|

|

21' 31" |

A1 |

| -

Introitus: Terribilis est |

|

3' 38" |

|

|

| -

Kyrie XII |

|

1' 30" |

|

|

| -

Gloria XII |

|

2' 38" |

|

|

| -

Graduale: Locus iste |

|

2' 15" |

|

|

| -

Alleluia Adorabo |

|

2' 30" |

|

|

| -

Offertorium: Domine Deus |

|

1' 59" |

|

|

| -

Sanctus XII |

|

1' 19" |

|

|

| -

Agnus Dei XII |

|

1' 14" |

|

|

| -

Communio: Domus mea |

|

3' 54" |

|

|

| IN

I VESPERIS |

|

|

3' 49" |

B1 |

| -

Hymnus: Urba Jerusalem |

|

2' 55" |

|

|

| -

Antiphona ad Magnificat in I

Vesperis: Sanctificavit |

|

0' 54" |

|

|

| AD

MATUTINUM |

|

|

12' 14" |

B2 |

| -

Invitatorium et Psalmodia: Dimus Dei |

|

8' 31" |

|

|

| -

Responsorium: Fundata est |

|

3' 43" |

|

|

| AD

LAUDES |

|

|

6' 05" |

B3

|

| -

Antiphonae per horas: |

|

|

|

|

| -

- Domum tuam |

|

0' 19" |

|

|

| -

- Domus mea |

|

0' 19" |

|

|

| -

- Haec est domus Domini |

|

0' 27" |

|

|

| -

- Bene fundata est |

|

0' 17" |

|

|

| -

- Lapides pretiosi |

|

0' 33" |

|

|

| -

Hymnus: Angularis fundamentum |

|

2' 59" |

|

|

| -

Antiphona ad Benedictus: Zachaee |

|

1' 11" |

|

|

| IN II VESPERIS |

|

|

0' 39" |

B4 |

| -

Antiphona ad Magnificat in II

Vesperis: O quam metuendus est |

|

0' 39" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CHOEUR DES MOINES

DE L'ABBAYE NOTRE-DAME DE

FONTGOMBAULT |

| Dom G. Duchêne,

Maître de choeur |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Abbaye

Notre-Dame de Fontgombault

(Francia) - 17/19 ottobre 1977 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Production |

|

Dr.

Andreas Holschneider |

|

|

Recording

supervision |

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

ARCHIV

- 2533 359 - (1 LP - durata 45'

03") - (p) 1978 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

ARCHIV

- 435 032-2 - (4 CD's - durata 78'

14"; 73' 13"; 71' 18" & 73'

54" - [CD3 1-17]) - (c) 1993 - ADD

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Codex

Albi (Paris, Bibliothèque

Nationale, lat. 776; geschrieben

vor 1079), fol. 9r

Dedicatio ecclesiae:

Introitus-Antiphon Terribilis

est locus iste (Aquitanische

Notation)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The Tradition of

the Gregorian Chant (VI)

Notre-Dame de

Fontgombault - Dedicatio

ecclesiae

The Dedication of a Church is

the name given to the liturgical

rite by which a new building

designed for public worship is

withdrawn from secular use and

consecrated to God and His

service. Each succeeding year a

special feast-day is set aside

to perpetuate the memory of this

solemn consecration.

Before 1961, when for pastoral

reasons this rite was

much simplified and abbreviated,

the ancient Ordo for the

dedication of a church was

marked by an extraordinary

wealth of symbolism, arising

from a felicitious blending of

the original Roman and Gallican

rites, a synthesis which dates

from the tenth century.

The most ancient document in our

possession concerning the Roman

rite comes from the sixth

century (Letter of Pope Vigilius

to Bishop Profuturus of Braga in

Portugal, written in 538). The

first generations of Christians

built no churches. Since the

early Church was not recognised

by the Roman state and was, at

least sporadically, liable to

active persecution, Christian

worship had to be carried out in

outlying villas and houses lent

for the purpose by memhers of

the Roman governing class who

were also members of the

Christian congregation. The

precariousness of such

arrangements for worship made it

impossible to consecrate any

building to the exclusive

service of God by a formal rite.

But this circumstance was not

the only reason. Christians were

profoundly convinced the worship

of God had a spiritual

significance that transcended

all considerations of place.

Thus about the year 57 St. Paul

wrote to the Corinthians: “Are

you not aware that you

yourselves are God’s temple in

which His spirit dwells?... The

temple of God is holy, and you

are that temple.” Reinforcing

this conviction among Christians

was a profound horror of the

religious materialism prevalent

in the surrounding pagan world,

of their temples and their

idols; and it was this which

earned the Christians of the

second century the reputation of

atheists. On the other hand a

custom arose in very early times

of offering the Holy Sacrifice

i. e. celebrating Mass, on the

tombstone of the newly dead pro

dormitione (for the repose

of the dead person’s soul). The

Liber Pontificalis attributes to

Pope Felix I (274) the custom of

celebrating Mass on the martyrs’

tombstones. This fact explains

the traces of liturgical worship

to be found in cemeteries

(funerary Chapels, rooms in

which the agape could be

celebrated).

In spite of this we know from

the historian Eusebius that as

early as the fourth century

there were numerous and

magnificent dedications of

church buildings. These were of

course made possible owing to

the decree of the Emperor

Constantine (313) which

inaugurated a period of peace

for the Christian Church. In the

earliest times the Roman rite

was simple. It took two

different forms, depending upon

whether the church to be

consecrated possessed relics of

the martyrs or not. If there

were no relics, the celebration

of a single Mass was deemed

sufficient to consecrate the

building: from that moment the

altar was considered consecrated

and the church itself dedicated

to Almighty God. If the new

church was to be the repository

of relics, Mass was preceded by

the ceremony of their reception

and deposition, though the Mass

itself remained the essential

part of the rite of dedication.

In the seventh century a third

element was added to this rite,

namely a purification of both

altar and church building by

aspersion, or sprinkling, with

previously blessed water.

In the Gallican rite the terse

and functional Roman liturgy was

extended by a large number of

complementary rituals. Probably

the description of the earliest

Galliean order for the

Dedication of a Church is to be

found in the eighth century

Gelasian Sacramentary from

Angouléme. In addition to the

Mass and the deposition of

relics we find here preparatory

rites of purification and

consecration of the church

building and especially of the

altar, the sanctification of

which was considered as an

essential part of the Gallican ordo.

All these rites took their

direct inspiration from the Old

Testament and have much in

common with the rites

accompanying the reception of

converts, or catechumens,

into the Christian Church

(exorcisms, aspersions,

anointings with holy oil). Still

further elements, whose origins

are obscure, were later added:

the bishop knocking at the door

before taking possession of the

church, the tracing on the floor

of the Greek and Latin

alphabets. The spiritual

significance of these various

ritual gestures is explained and

emphasised by a wealth of psalms

and antiphons. Thus Christ

Himself is the corner-stone

supporting the “living stones”

representing the faithful who

form the Church, represented as

the Bride and Body of Christ,

the Holy Temple of the Lord.

Churches of wood and stone are

presented as no more than

earthly foreshadowings of the

Heavenly Jerusalem.

According to the Liber

Pontificalis the Mass Terribilis

and the pieces forming the

office for the Dedication of a

Church wewe composed about the

year 608 for the dedication by

Pope Boniface IV (608-615) of

the ancient Pantheon as a

church, under the title of

“Saint Mary of the Martyrs”,

'the Pope having had a large

number of bones transported from

the catacombs, as relics. In the

Little Roman Martyrology this

event is commemorated on May 13,

a feast which also figures under

the same date in later

martyrologies. It appears in all

copies of the Antiphonale

Missarum, and the office of this

feast has in fact become the

‘Common for the Dedication of a

Church’. Although the date of

composition is early, the

sources of the text are various

and not simply the psalter, as

in the case of earlier pieces.

The sequence of these different

texts forms in fact a long and

magnificent poem, a profound and

rarely equalled evocation of all

the mystical aspects of the

feast - Jacob pouring oil over

the memorial pillar at Bethel,

first dedication; the dedication

of the Temple in Jerusalem by

King Solomon, the dedication of

the Christian soul at baptism,

and lastly that of the heavenly

temple blessed by the Lord

Himself - that ultimate reality

of which all earthly dedications

are no more than “sacraments”,

outward and visible signs. Just

as it was Christ’s blood that

opened and consecrated the

sanctuary of eternity for

mankind (Hebrews IX, 23), so it

is in this same Precious Blood

that Christians are dipped and

purified to enter the Church.

The deposition of the martyrs’

relics within the altar-stone is

a realistic reminder of blood

shed on God’s behalf and proof

of total commitment to Him. In

this way the feast of the

Dedication of a Church brings

together into a single liturgy

the saints in heaven and the

faithful on earth, as they

journey towards the Heavenly

City.

On the first side of this disc

we find the Proper of the Mass

for the Dedication of a Church

with the Ordinary (Kyrie,

Gloria, Sanctus, Agnus Dei)

which bears the number XII in

the Vatican edition of the

Graduale Romanum. The earliest

copy of this Ordinary comes from

Metz and belongs to the eleventh

century. The style of all the

constituent pieces is simple and

homogeneous, and it must have

been fairly widespread during

the middle ages, since it

appears in numerous manuscripts

of the twelfth century.

According to missals of that

time it was used only for major

feasts.

The entrance antiphon, Terribilis

est (Awesome is this

place), is taken from Genesis

XXVIII, 17 and describes the

reverent awe and sense of

adoration felt by Jacob on

waking from his dream at Bethel;

and a deep sense of wonder and

religious recollection are

precisely what this music

communicates. The three

components of the melody are

virtually symmetrical and unfold

according to a severely balanced

line, deliberately restricted to

the lower part of the modal

scale. This creates a solemn and

meditative atmosphere preserved

from heaviness by the fact that

the note-values are all small.

In complete contrast the psalm

is an enthusiastic and

light-hearted celebration of the

soul’s joy in God’s presence.

In the series of gradual

responses there is one, Locus

iste (This place), which

stands apart from the rest. It

consists of a single versicle,

and whereas the other gradual

responses are taken for the most

part from the Psalter, this is

the composition of a churchman.

The most recent liturgical

studies suggest that the author

was a Roman cleric who drew his

inspiration from an antiphon in

the Mozarabic liturgy drawn from

the apocryphal fourth book of

Esdras. The basic idea expressed

is that the Church is no more

than the sacramentum

(“type”, or foreshadowing) of

the Heavenly Temple which is

God’s throne. The music of the

Response suggests a deep sense

of reverence, but in the

versicle it rises and expands in

one of the finest “centonised”

formulas (1) of mode V.

The Alleluia versicle Adorabo

is taken from Psalm 137, and it

is hard to imagine a melodic

line better suited to such a

text. The expression of

adoration (long descending

notes) and then of praise (the

long melisma on “confitebor”) is

perfectly conveyed by the music.

The Offertory antiphon Domine

Deus is taken from the

First Book of Chronicles XXIX,

17-18. It is part of David’s

beautiful prayer after learning

that his son Solomon would

achieve the work which he

himself had desired and prepared

with such devotion: the building

of the temple. “I know, O God,

that Thou soundest men’s hearts

and lovest righteousness. As for

me, it is with a righteous heart

that I have given everything,

and it is with joy that I see

Thy people assembled to make

offerings. Lord God of Abraham,

Isaac and Israel, our

forefathers preserve for ever

this willingness in the heart of

Thy people ...”. Mode VI,

serenely tranquil, is

particularly well suited to

convey the feelings of the

giver: simplicity and joy, all

the greater for the fact of the

totality of the gift (“obtuli

universa... cum ingenti gaudio”

- I have offered everything with

unbounded joy).

The Communion antiphon, Domus

mea (My house), consists

of several gospel texts (Matthew

XXI, 3; Luke XI, 10). It is a

vigorous statement of what God’s

house should be: a place of

prayer, where God is pleased to

grant the requests of his

faithful people. Like a

processional chant, the antiphon

alternates with a number of

verses from Psalm 83.

Side 2 contains a large number

of extracts from the Office for

the Dedication of a Church. It

begins with the hymn for First

Vespers, Urbs Jerusulem

beata (Jerusalem heavenly

city), an admirably poetic

celebration of “the dwelling of

God among men” in a blessed

eternity, the heavenly Jerusalem

described in the twenty-first

chapter of the Book of

Revelations. It was composed

about the eighth century, and

the unknown author made use of

many quotations from Saint

Gregory the Great, whose own

scriptural sources can be found

in the books of Tobias, Isaiah,

Daniel and the Revelations. The

hymn is in eight verses, the

first four of which are assigned

to Vespers of this feast, the

other four to Lauds. Each of

these groups ends with the same

‘doxology’, i. e. a final verse

ascribing honour to the three

persons of the Blessed Trinity.

The earliest manuscript of this

hymn belongs to the ninth

century.

The Magnificat antiphon for

First Vespers, Sanctificavit,

is a not particularly original

First Mode melody, calm and

serene in character.

The canonical hour of Matins (a

night office that used in early

days to be called vigil

or “watching”) opens every day

with a short versicle followed

by Psalm 94, which is an

invitation to celebrate God’s

praises (“Venite exsultemus

Domino ... adoremus et

procidamus ante Deum” - O come,

let us sing unto the Lord ...

let us worship and bow down

before Him). A short antiphon,

sung first by a single voice and

then by the whole choir,

precedes the psalm itself and

establishes the liturgical

character of each day. This

antiphon is repeated, wholly or

in part, like a refrain, between

each verse of the psalm. The

music of the Invitatory, always

circling round the tenor, is

very varied in expression and

forms one of the most beautiful

recitatives in the whole Office.

The formula of mode VII, which

is used here, is moulded on the

corresponding tone of the Matins

response.

The main body of Matins consists

of psalms and readings, divided

into three groups known as

“nocturns”. Each reading, or

“lesson”, is sung by a soloist

and followed by a response sung

by the choir. This piece

maintains the typical structure

of the response - a b a,

in which a represents

the body of the response and b

the versicle. The Gloria Patri

follows the last response of

each nocturn. Like most of the

Matins responses, it is

“centonised”. The text is taken

from Isaiah II, 2-3, while the

versicle comes from Psalm 125.

The five antiphons which follow

belong to the Office of Lauds,

where they are sung before the

psalms, and all of them except

the fourth belong also to one of

the so-called “little” Hours

(Prime, Terce, Sext and None).

They are short pieces in the

“syllabic” style i. e. with no

more than one note to each

syllable.

Then comes the second part of

the hymn Urbs Jerusalem

beata (vv. 5-8). It has

been thought by some that vv. 7

and 8 are a later addition,

since v. 6 resembles a doxology

(“Trinum Deum unicumque...”).

Finally the two following

antiphons, more important and

ornate than those of Lauds,

belong to canticles of Second

Vespers (Magnificat) and

Lauds (Benedictus). The

most noteworthy is that of

Lauds, Zachaee, a real

musical miniature of the scene

described in the gospel of the

day (Luke XIX, 5-6,9). Observe

the delicacy with which the

composer has emphasised the key

words of the text; the outburst

of joy on “hodie”, the moment of

tenderness on the podatus

of “tua” (marked by a tenete,

or as we should say tenuto,

in the manuscripts) and the

great strength and solidity of

the final phrase “Hodie huic

domui salus a Deo facta est”

(This day salvation has come to

this house), a succession of

long notes in the manuscripts.

Interpretation

The abbey of Fontgombault was

founded in Berry, on the banks

of the Creuse, by Pierre de

l’Etoile in 1091. Much damaged

during the religious wars of the

sixteenth century, it was

magnificently restored during

the seventeenth, only to fall

largely into ruin during the

eighteenth. Restored by a

churchman of great faith during

the nineteenth century it was

used by Trappists until 1904,

when it became a seminary. It

was only in 1948 that

Benedictines of the French

Congregation restored the abbey

to its original use. The group

of monks which in that year came

from Solesmes naturally brought

with them the style and method

of interpretation elaborated by

the then choirmaster of

Solesmes, Dom Gajard. These had

been tested for many years and

they remain today the principles

governing the interpretation of

Gregorian chant at Fontgombault.

Their chief object is to

emphasise the flexibility and

purely musical character of the

melodic line and the freedom of

rhythm. These are the essential

qualities in the development of

sung prayer, which is the

primary object of Gregorian

chant.

The Mass texts used are those of

the Vatican version in use at

the abbey (Graduale

sacrosanctae Romanae Ecclesiae,

1908 edition); the Office texts

are taken from the Antiphonale

monasticum (1935 edition),

the Liber Responsorialis

juxta ritum monasticum

(1895 edition) and the Processionale

monasticum (1893 edition).

The recording was made in the

abbey church at Fontgombault and

the singers are the members of

the community.

Dom

G. Duchêne

Translator:

Martin Cooper

(1) Centonised

- this was a recognised

practise, consisting of

devising a passage out of

disparate

fragments of Gregorian

melody, and the art lay in

forming a convincing unity

from a mosaic of

melodic phrases each of

which was removed from its

normal context.

|

|

|