|

|

1 LP -

2533 284 - (p) 1975

|

|

| 4 CD's -

435 032-2 - (c) 1993 |

|

| THE TRADITION OF

THE GREGORIAN CHANT - (IV) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DUOMO

DI MILANO - Canti Ambrosiani |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CANTUS

MISSAE |

|

|

49' 41" |

|

| -

Ingressa: Respice in me |

viri

|

1' 34" |

|

A1 |

| -

Psalmellus: Pacifice loquebantur |

viri

|

3' 44" |

|

A2 |

| -

Alleluia: Magi venerunt |

viri et pueri |

6' 34" |

|

A3 |

| -

Ante Evangelium: In Bethlehem Judae |

pueri |

1' 01" |

|

A4 |

| -

Post Evangelium: Coenae tuae |

pueri

|

1' 36" |

|

A5 |

| -

Ante Evangelium: Laudate dominum |

pueri

|

1' 14" |

|

A6 |

| -

Post Evangelium: Domine, domine deus |

viri |

1' 22" |

|

A7 |

| -

Offertorium: Ubi sunt nun dii |

viri |

2' 48" |

|

A8 |

| -

Confractorium: Ille homo |

viri |

1' 17" |

|

A9 |

| -

Transitorium: Gaude et laetare |

viri

et pueri

|

2' 24" |

|

A10 |

| -

Transitorium: Te laudamus |

viri

et pueri |

1' 59" |

|

A11 |

| CANTUS

OFFICII |

|

|

|

|

| -

Hymnus: Splendor paternae gloriae |

viri et pueri |

3' 51" |

|

B1 |

| -

Hymnus: Agnes beatae virginis |

viri et pueri |

3' 30" |

|

B2 |

| -

Hymnus: Apostolorum passio |

viri et pueri |

2' 40" |

|

B3 |

| -

Antiphona: Omnes patriarchae |

pueri |

1' 17" |

|

B4 |

| -

Responsorium: Tenebrae factae sunt |

viri |

3' 45" |

|

B5 |

| -

Antiphona: Rorate caeli |

viri et pueri |

1' 37" |

|

B6 |

| -

Antiphona: In exitu Israel |

viri et pueri |

1' 16" |

|

B7 |

| -

Antiphona duplex: Venite omnis

creatura |

viri et pueri |

1' 53" |

|

B8 |

| -

Psallenda: Pax in caelo |

viri et pueri |

1' 26" |

|

B9 |

| -

Psallenda: Videntes stellam magi |

viri et pueri |

1' 37" |

|

B10 |

|

|

|

|

Sources:

1. Antiphonale Missarum iuxta

ritum Mediolanensis Ecclesiae,

Paris/Tournai/Rom, 1935 (Desclée

& Socii)

2. Vesperale iuxta ritum

Mediolanensis Ecclesiae,

Paris/Tournai/Rom, 1939 (Desclée

& Socii)

Die Ausgaben wurden für diese

Aufnahme nach den Quellen kritisch

revidiert und ergänzt von Ernesto

Moneta Caglio. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CAPPELLA MUSICALE

DEL DUOMO DI MILANO |

| Monsignore Luciano

Migliavacca, Direttore |

| Luigi Benedetti

(voci maschili) |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Chiesa

di S. Ambrogio, Milano (Italia) -

22/25 ottobre 1974 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Production |

|

Dr.

Andreas Holschneider |

|

|

Recording

supervision |

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

ARCHIV

- 2533 284 - (1 LP - durata 49'

41") - (p) 1975 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

ARCHIV

- 435 032-2 - (4 CD's - durata 78'

14"; 73' 13"; 71' 18" & 73'

54" - [CD4 11-30]) - (c) 1993 -

ADD

|

|

|

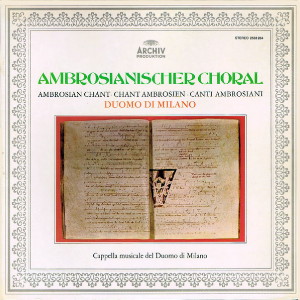

Cover |

|

Ms.

London, British Museum,

Antiphonarium Ambrosianum, Codex

Add. 34 209 (12. Jh.). ff. 8v - 9

Reproduced by permission of the

British Library Board |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The Tradition of

the Gregorian Chant (IV)

Duomo di

Milano - Canti Ambrosiani

Ambrosian chant is better

understood if one bears in mind

the fact that throughout the

Christian West, until about 1000

A.D., many different religious

rites were in use, but that they

gradually all gave place to the

increasingly authoritative Roman

liturgy - with the sole

exception of the liturgy

employed at Milan. This has

remained almost unaltered, with

its own plainsong melodies, from

its origins in the 4th century

right through to the present

day, a span of almost sixteen

centuries. Why at Milan?, one is

bound to ask.

By the end of the 4th century

Christianity had triumphed over

paganism as the new State

religion, despite violent

disputes with sects holding

heretical views, in particular

the Arians. At that time

Mediolanum, as Milan was then

called, together with the

seaport of Aquileia (which today

is a mere inland village owing

to the silting up of its shores

over the centuries, but which

still possesses extremely

impressive remains of its former

glory), was the most important

Imperial capital city in the

western half of the mighty

Imperium Romanum Christianum. A

government official in Milan who

was also greatly gifted as a

writer, poet and orator,

Aurelius Ambrosius (339-397) was

chosen by the people as their

Bishop in 374 A. D. I-Ie was

responsible to no small degree

for the leading position which

Milan came to occupy among

cities as “Roma secunda”. The

authority of this powerful

personality led to the

adaptation of the terme

“Ambrosian” for the Milanese

liturgy and its plainsong

melodies since the 9th century.

Formerly they were used almost

everywhere in northern Italy,

and in parts of southern Germany

(Augsburg, Salzburg, Prague

etc.), but today the Ambrosian

liturgy is restricted to the

city of Milan and its

surroundings, and to a few

valleys in the southern Alps.

Until 1898 a special Milanese

form of musical notation was in

use, but in 1935 it was

superseded by the customary

Roman square note system. This

form is used in the edition of

the Ambrosian Mass chants

produced by the Montserrat

Benedictine G. M. Suñol (1935),

although as the facsimile shows,

the authentic Milanese neumes

are easier to read. For this

reason the first new edition of

the complete Milanese chants in

the Monumenta Monodica Medii

Aevi 13/14 (by Bonifazio

Baroffio) returns to the use of

the old notation, and also

corrects various errors in

Suñol’s edition.

Milan’s overriding importance as

seat of the Imperial government

with its worldwide trade links,

effected the liturgy. Outside

influences were accepted more

readily there than, for example,

in Rome, which at that time was

a less important, almost

provincial city. Liturgical

elements from elsewhere came

into use at Milan between the

5th and the 7th century. From

Rome, Milan adopted a number of

Introit chants, which became

known as Ingressae (e. g. No.

1), and certain Graduals now

known as Psalmelli (No. 2). From

the East came some Byzantine

texts, such as “Coenae tuae”,

sung by the Milan Schola as No.

5; this was sung at Byzantium

from the 6th century onwards,

and may go back to an even

earlier Syrian-Palestinian

tradition. Unfortunately,

despite intensive research it

has not yet proved possible to

discover or reconstruct the

original Oriental melodies to

these texts, and the same is

true of other Ambrosian chants

whose words the editor of

Paléographie Musicale 5/6

(Cagin) has shown to be

translations of texts from

Eastern liturgies. Certain

melodic configurations may

possibly have reached Milan from

rites which had originated in

Gaul; I have in mind the typical

formal characteristics of “In

Bethlehem Judae” (No. 4) and of

the two Transitories (Nos. 10

and 11) sung during the

reception of the Communion. Here

the melody consists of more or

less numerous repetitions of a

single melodic line (comparable

to such Gallic pieces as the

“Exultet”; also, to quote a late

example, the earliest French

crusaders’ hymn of 1147). To sum

up: Milan was receptive to the

good and beautiful from whatever

source, while Rome deliberately

excluded many outside

influences, for example

restricting the texts used to

those from the Psalms. This gave

the Milanese liturgy as a whole

a more colourful character, its

plainsong providing contrast to

the more uniformly sober Roman

form. Seen in another light, the

contrast was between the

inorganic compilation of

variegated material at Milan,

and the strictly constructed

Roman edifice.

The important thing is that the

chants imported from elsewhere

were creatively transformed in

accordance with the stylistic

characteristics of Ambrosian

plainsong, “Ambrosified” so to

speak. This brings us to the key

question: What is the

distinguishing characteristic of

the Ambrosian style? Let us for

the moment ignore the wider

liturgical context, the typical

ordering of the chants for the

Mass (Nos. 1-11) and Offices

(Nos. 12-21), on which this

recording is based, and consider

solely the melodic style evident

in the chants as a whole. What

first attracts our attention is

the constant repetition of

innumerable melodic fragments

moving by small intervals; the

Bavarian “Scholasticus” Aribo

termed this method of melodic

progress “spissim” in contrast

to “saltatim”, the use of wider

leaps favoured in northern

lands. (The use of small

intervals was a hallmark not

only of Milanese but also of

early Roman and Beneventan

chants, and with Oriental

melodies Byzantine and Syrian in

particular, so that it is

correct to consider this a

characteristic of vocal music in

Mediterranean lands). The

melodic repetitions are not

always literal, being subjected

to slight modifications or

“Gestalt”- variations, as they

have been called. Consequently

the Milanese chants appear, to a

greater extent than others, to

be permeated with music, as such

motifs are constantly in

evidence. By comparison Roman

plainsong creates an effect of

austerity: the placing of the

individual notes or melodic

figures is subordinated to the

grammatical characteristics of

the text, while Milanese

plainsong flows apparently

unconcernedly across sentences,

verbal phrases and caesuras.

Its range extends from simple

Antiphons like the Advent

“Rorate” (No. 17) and “In exitu”

(No. 18), called syllabic

because in such pieces it is

rare for a syllable to be spread

over more than one note, right

through to the extravagant

melismata of the “melodiae”, in

which up to 200 notes are sung

to a single syllable (No. 3,

more details of which are given

below). Between these two

extremes the great majority of

the chants are in a mixture of

the syllabic and melismatic

styles. Examples of this among

the chants for the Mass given

here are the Ingressa (No. 1),

which fulfils some of the

functions of the Roman Introit,

the two chants intoned between

the lessons “Laudate” (No. 6)

and “Domine, domine deus” (No.

7), the Confractorium “Ille

homo”, the chant to accompany

the breaking of the bread (No.

9). From among the chants for

the Divine Office the Schola

sing the “Venite omnis creatura”

(No. 19), put together from two

Antiphons, the Psallendae Nos.

20 and 21 which serve to frame a

Psalm, and the celebrated

“Tenebrae factae sunt” of Holy

Week (No. 16); the three Hymns

(Nos. 12-14) are referred to

below. They are followed by the

“Omnes patriarchae” (No. 15),

which is preceded liturgically

by the Benedictus of the three

youths in the fiery furnace,

classified as a Hymn. More

richly melismatic in style are

the Psalmellus “Pacifice” (No.

2), the counterpart to the Roman

Gradual, and the Offertory “Ubi

sunt nunc dii” (No. 8), whose

reference to “false” gods

suggests that it dates from a

time when heathenism was still a

force to be reckoned with. At

the other end of the stylistic

spectrum are the melodic

patterns whose melismatic

richness is without parallel:

These are the “melodiae cum

infantibus”, a true Milanese

creation (No. 3). A long

Alleluia - St. Augustine had

warm praise for its chains of

notes which he called “jubilus”

- acts as a refrain framing the

heart of the piece which tells

of the coming of the Three Wise

Men, the “Magi venerunt”. First

it is sung by men’s voices, then

a repeat follows in which boys’

voices take part - this is an

extended version known as

“melodiae primae”; for the third

and last time it is sung by the

boys to conclude the piece in a

yet more radically altered

version, the “melodiae

secundae”. “To present a ‘scheme

of motifs’ is not in accordance

with the style of the melodiae.

It is better to surrender to the

flow of this infinitely

fine-nerved line, and at the

same time to observe how the

same or similar figures

constantly recur. It will also

be observed that lengthy

stretches are repeated, and

finally it becomes apparent that

brief and longer sections are

not put together haphazardly as

seems at first to be the case,

but that a formative will is in

sovereign command of the

endlessly flowing melodies” (B.

Stäblein, “Das Schrifthild der

einstimmigen Musik des

Mittelalters”, Illustrations 21

a and b, P. 132). Franchino

Gaffori (died 1522), who

directed the Cathedral music in

Milan for 38 years and after

whom the present Schola is

named, gave a masterly

description of the evolution and

fine flow of the melodic line

when he referred to a

“continuato et perenni

transitu”, a species of endless

melody.

In addition to the “melodiae cum

infantibus” Milan created

another new class of

composition, which - unlike the

“melodiae” which remained unique

to Milan - soon came into use

throughout the whole of the

Latin Church: the Hymn (Nos.

12-14). Its origin is known:

when their Arian foes were

holding the Bishop and his

faithful followers prisoner in

Porziana Basilica for several

days and nights in an attempt to

compel their submission, Ambrose

kept his people from succumbing

to weariness by teaching them

hymns whose words he had

written, and which they then

sang. The basic form (8

four-line verses, sung

antiphonally by men and women)

and the style of writing, with

profound ideas expressed in

words which all could easily

understand, were soon taken up

by all churches and called

simply Ambrosiani. These hymns

had a striking effect on the

masses in Milan: they were sung

so enthusiastically by the

populace that the Arian foes

described them as magical songs

(in-cantationes) with which the

Bishop had turned the people’s

heads - an accusation which gave

Ambrose cause for pride. All

three hymns sung here, the

well-known “Splendor paternae

gloriae” (Monumenta Monodica

Medii Aevi 1, Melody 3), “Agnes

beatae virginis” (ditto, 24) and

“Apostolorum

passio” (12), are given at their

first appearance in the sources

(12th century) in the authentic

and best Ambrosian tradition,

including the addition of the

customary melismata.

Caption to the illustration

on the title page:

One of the earliest manuscripts

of Ambrosian chant, dating from

the 12th-13th century: British

Museum, London, Add. 34209

(Facsimile and transcription in

Paléographie Musicale 5 and 6)

fol. 8v/9 (the page numbers 16

and 17 pasted on refer to the

Paléographie Musicale edition).

The lines (partly coloured)

which are marked with pitch

indications (c, f, b, a) along

with the “Custodes” which

indicate the melodic

continuation at the end of each

line, facilitate an easy reading

of the notation - an ability

which can be acquired very

quickly with the aid of a good

introduction to the subject.

These are chants for the Office

of the 3rd and 4th Sundays in

Advent; finally, below on the

right, the Responsorium “Veni

domine” (with Initial) and the

two verses “Deus in adiutorium”

and “Confundantur”.

Bruno

Stäblein

Translator:

John Coombs

····················

Si avrà per il corale ambrosiano

una comprensione migliore se si

pensa che nei paesi occidentali

cristiani esistevano fino alla

fine del millennio una quantità

di riti, che nel corso dei

tempi, dovevano cedere di fronte

alla liturgia romana, la quale

si estendeva sempre più potente

- con l’unica eccezione di

Milano che riuscì a mantenere la

propria liturgia, con le sue

proprie melodie, dagli inizi del

quarto secolo fino al giorno

d’oggi, per quasi sedici secoli.

Perché proprio Milano? ci si

clomanderà.

Nei tempi decisivi della fine

del IV secolo, dopo lo

scioglimento del paganesimo

attraverso la già strapotente

nuova religione di stato

cristiana e dopo le violente

dispute con le sette,

specialmente con gli ariani,

Mediolanum - così si chiamava

allora Milano - insieme alla

città di porto Aquileia (oggi

per l’alzamento d’arena divenuta

niente più che un villaggio

dell’interno, però con imponenti

resti dello splendore passato)

era la capitale imperiale più

importante della metà

occidentale dell’enorme Imperium

Romanum Christianum. Uno dei

funzionari del governo qui

residenti era Aurelius Ambrosius

(339-397), molto qualificato

anche come scrittore, poeta e

retore, che la popolazione aveva

eletto vescovo nel 374. Era

proprio lui la persona a cui

Milano doveva la sua posizione

dominante come "Roma secunda".

L’autorità di questa personalità

energica ha condotto al fatto

che dal 9° secolo in poi la

liturgia milanese e il suo

tesoro melodico furono chiamati

"amhrosiani". Mentre prima la

loro area di diffusione si

estendeva in quasi tutta

l’Italia settentrionale fino a

parti della Germania meridionale

(Augusta, Salisburgo, Praga),

oggi il rito ambrosiano si

limita alla città di Milano e ai

suoi dintorni, come pure ad

alcune valli dell’orlo alpino

meridionale. Anche la scrittura

musicale milanese in uso fino al

1898 fu sostituita nel 1935

dalla scrittura quadrata

tipicamente romana: così nella

nuova edizione dei Canti

Ambrosiani per Messa (1935)

curata dal Benedettino di

Monserrat G. M. Suñol, benché la

scrittura originaria dei neumi

milanesi, come il facsimile

mostra, sia di lettura più

facile. Perciò anche la prima

nuova edizione del completo

repertorio milanese in

"Monumenta Monodica Medii Aevi

13/14" (curata da Bonifazio

Baroffio) riprenderà l’antica

scrittura e allo stesso tempo

correggerà gli altri difetti

dell’edizione di Suñol.

Lo straordinario significato di

Milano come sede del governo

imperiale con relazioni

commerciali mondiali ebbe i suoi

effetti anche sulla liturgia,

nella quale ci si mostrò più

aperti agli influssi stranieri

di quanto, per esempio, ci si

mostrasse nella Roma di allora,

modesta e quasi provinciale.

Infatti si possono dimostrare

nel IV e nel V secolo importi

dalle liturgie straniere. Milano

ha preso da Roma una gran

quantità di Canti d’Introito,

che presero il nome "Ingressae"

(per es. nr. 1), anche alcuni

"Graduali" che ora si chiamano

"Psalmelli" (nr. 2). Da fonti

orientali provengono alcuni

testi bizantini, come per

esempio "Coenae tuae" (nr. 5)

eseguito dalla Schola Milanese,

cantato a Bisanzio a partire dal

VI secolo e che possibilmente

risale all’ancora più antica

tradizione siro-palestinese.

Purtroppo, nonostante gli sforzi

piu intensi, fino ad oggi non si

sono potute né trovare né

ricostruire le corrispondenti

melodie orientali originali, e

ciò vale anche per gli altri

canti ambrosiani che secondo

l’accurato ed esperto studioso

di Paléographie Musicale 5/6

(Cagin) sono traduzioni di testi

della liturgia orientale. Da

alcune forme simili al "Lied"

possiamo supporre che siano

forse penetrati a Milano

dall’ambito dei riti in uso in

Gallia, per esempio le forme

così tipiche del "In Bethlehem

Judae" (nr. 4) e i due

Transitori (nr. 10 e 11), che si

cantano al momento della

Comunione. Qui la melodia

consiste in ripetizioni più o

meno numerose di una singola

riga di melodia (confrontabile

tra l'altro con l’"Exultet"

sorto in Gallia, e per citare un

esempio più tardo, col più

antico canto crociato francese

dell’anno 1147). Per concludere:

Milano è stata aperta al bello e

al buono dove lo trovava, mentre

Roma si tenne volutamente chiusa

ad alcuni influssi stranieri e,

per esempio, per quello che

riguarda i testi, si limitò ai

Salmi. Da ciò l’impressione

colorita della liturgia milanese

e dei suoi tipi di melodia in

contrasto a quella romana,

sobria, quasi monocolore,

oppure, se si vuol vedere la

cosa sotto un altro punto di

vista: lo stile inorganico,

aperto a tutti gli influssi di

Milano, di fronte alla severa

costruzione di Roma, chiusa in

sé.

Importante è ora il fatto che i

canti importati sono stati

trasformati in maniera creativa,

secondo le particolarità

stilistiche delle melodie

ambrosiane, così per dire sono

stati "ambrosianeggiati". Così

arriviamo alla questione

centrale: Che cos’è lo stile

ambrosiano? Qui non vogliamo

occuparci delle particolarità

liturgiche, dell’ordinamento

tipico dei canti per Messa (nr.

1-11) e dell’Uffizio (nr.

12-21), come sono presentati in

questa scelta, ma ci limitiamo

allo stile melodico diffuso in

tutti i canti. Ciò che colpisce

subito l’occhio oppure

l’orecchio è la continua

ripetizione di quelle

innumerevoli piccole unità

melodiche che si muovono in

piccoli passi: "spissim" viene

chiamato questo genere di

progredire melodico dallo

scolastico bavarese Aribo,

contrapposto a "saltatim" il

modo di procedere più a salti,

preferito dai popoli nordici (la

tecnica spissim è patrimonio

comune di Milano, della musica

vecchio-romana, di quella di

Benevento e anche delle melodie

orientali, soprattutto di quella

bizantina e siriaca, così che, a

ragione, si parla di uno stile

canoro mediterraneo). Qui si

tratta non solo di ripetizioni

consequentemente immutate, ma

anche di leggere trasformazioni,

di variazioni di forma - così si

sono chiamate - in modo che i

canti milanesi appaiono più

degli altri incorporati nella

musica, perché tali "motivi"

sono incastrati dappertutto. In

confronto a questi la melodia

romana è piuttosto parca: ordina

la conduttura in note singole,

oppure la melodia consistente in

gruppi plastici e afferrabili è

subordinata alle particolarità

grammaticali del testo, mentre

la melodica milanese inonda

senza di distinzione, frasi,

periodi, cesure.

Il suo campo si estende dalle

semplici Antifone, come il

"Rorate" dell’Avvento (nr. 17)

oppure "In exitu" (nr. 18), nei

quali cade solo raramente più di

una nota su una sillaba (Perciò

chiamata sillabica), giù per

tutta la scala fino agli

esorbitanti melismi della

"melodiae", in cui su una

sillaba si cantano più di 200

toni (nr. 3, vedi sotto). Tra

questi due estremi c’è la grande

quantità dei pezzi di stile

misto, melismatico-sillabico. Di

quelli qui presentati per la

Messa sono gli "Ingressae" (nr.

1) che hanno ripreso alcune

funzioni dell’Introito romano, i

due canti tra le Letture

"Laudate" (nr. 6) e "Domine,

domine deus" (n. 7) il

Confractorium "Ille homo", canto

di accompagnamento al momento

della rottura del pane (nr. 9).

Dei pezzi dell’Ora canonica la

Schola canta il "Venite omnis

creatura" (nr. 19) composto da

due antifone, i due "Psallendae"

che fungono da cornice per un

salmo (nr. 20 e 21) e il celebre

"Tenebrae factae sunt" della

Settimana Santa (nr. 16); ai tre

canti (nr. 12-14 di cui parliamo

sotto) segue l’"Omnes

patriarchae" (nr. 15), che

nell’ordine liturgico è

preceduto dal Benedictus dei tre

adolescenti nella fornace di

fuoco ardente, denominato

Hymnus. Tendono più allo stile

melismatico: il Psalmellus

"Pacifice" (nr. 2), pezzo

corrispondente al Graduale

romano e l’Offertorio "Ubi sunt

nunc dii" (nr. 8) dei quali, per

il riferimento ai "falsi" dei si

suppone una data di composizione

in un tempo in cui il paganesimo

era ancora in certo modo

virulento. Alla fine della scala

ci sono poi composizioni di

ricchezza melismatica senza

uguale: sono le "melodiae cum

infantibus" vera e propria

creazione milanese (nr. 3). Un

lungo Alleluia - già

Sant’Agostino ha trovato parole

di lode per la catena di note da

lui chiamata Jubilus - racchiude

come un ritornello il vero e

proprio centro, l’annuncio della

venuta dei Re Magi, il "Magi

venerunt": la prima volta è

cantato da voci maschili, segue

poi una ripetizione a cui

partecipano i ragazzi (le voci

bianche) e precisamente in una

stesura chiamata "melodiae

primae"; la terza ed ultima

Volta cantano i ragazzi (le voci

bianche) la "melodiae secundae"

come finale, in una stesura

molto pi# elaborata. "Non

sarebbe adeguato allo stile

delle "melodiae" tentare di fare

uno schema dei motivi. È meglio

abbandonarsi allo scorrere di

questa linea infinitamente

sottile e osservare come si

presentano sempre forme eguali o

simili; si osserverà poi che

pezzi più lunghi si ripetono e

infine che le parti piccole e

grandi non sono allineate senza

regola - come potrebbe sembrare

in un primo momento - ma che c’è

una volontà che sta al di sopra

e guida sicura questo infinito

scorrere" (vedi B. Stäblein: Das

Schriftbild der einstimmigen

Musik des Mittelalters,

illustrazione 21a e b, pag.

132). Franchino Gaffori (+

1522), che diresse per trentotto

anni la musica del Duomo e di

cui l’odierna Scuola corale

porta il nome, caratterizza in

maniera magistrale lo

svolgimento e lo scorrere della

linea melodica, quando parla di

"continuato et perenni

transitu", dunque una specie di

melodia infinita.

Accanto alle "melodiae cum

infantibus" Milano ha creato un

secondo genere nuovo che però -

al contrario delle "melodiae"

rimaste milanesi - è divenuto

patrimonio comune di tutta la

chiesa in lingua latina: l’Inno,

Hymnus (nr. 12-14). L’origine ne

è nota: quando i nemici ariani

tennero rinchiuso il vescovo e i

suoi fedeli per molti giorni e

per molte notti nella Basilica

Porziana per costringerli a

cedere, Ambrogio, per evitare il

pericolo della stanchezza, fecc

studiare e cantare gli inni da

lui scritti. La loro forma

esteriore (otto strofe di

quattro versi ciascuna, cantate

alternativamente da voci

maschili e da voci femminili) e

il loro contenuto, esprimente

pensieri profondi in una lingua

facilmente comprensibile, furono

ripresi in breve da tutte le

chiese e chiamati semplicemente

ambrosiani. Il loro effetto

sulle masse fu immediato già a

Milano: i nemici ariani

parlarono di questi inni cantati

dal popolo con entusiasmo, come

di canti magici

(in-cantationes), con i quali il

vescovo voleva incantare il

popolo, un rimprovero di cui

Ambrogio era addirittura fiero.

Tutti e tre gli inni qui

cantati, il celebrc "Splendor

paternae gloriae" (Monumenta

Monodica Medii Aevi 1, Melodia

3), "Agnes beatae virginis"

(vedi sopra 24) e "Apostolorum

passio" (nr. 12) uscirono nel

loro primo apparire nelle fonti

(XII secolo) nella vera e

migliore tradizione ambrosiana,

con i soliti diffusi melismi.

Nota sull'illustrazione del

frontespizio:

Una delle più antiche scritture

di melodie ambrosiane del XII e

XIII secolo: Londra, Britisches

Museum, Add. 34209 (Facsimile e

trasposizione in Paléographie

Musicale 5 e 6), fol. 8 v/9 (i

numeri delle pagine incollati

sopra 16 e 17 si riferiscono

all’edizione della Paléographic

Musicale). Le linee in parte

colorate, contrassegnate con le

lettere chiavi (c, f, b, a), e

le "custodi" che indicano la

continuazione alla fine di ogni

riga di melodia, rendono

possibile l’agevole lettura -

presupponendo un'opportuna guida

- è una cosa che si può imparare

facilmcnte. I canti sono quelli

dell’Officium della III e IV

Domenica d’Avvento; per ultimo a

destra, sotto, il Responsorio

"Veni Domine" (con iniziale) e i

due versi "Deus in adiutorium" e

il "Confundantur".

Bruno Stäblein

Translator:

Maria Grazia

Kölling-Bambini

|

|

|