|

|

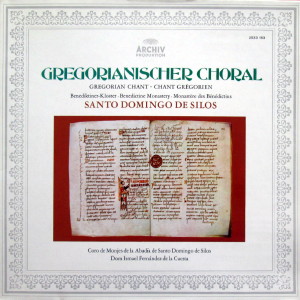

1 LP -

2533 163 - (p) 1974

|

|

| 4 CD's -

435 032-2 - (c) 1993 |

|

| THE TRADITION OF

THE GREGORIAN CHANT - (III) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SANTO

DOMINGO DE SILOS - Benedictine

Monastery

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ANCIENT

SPANISH CHANTS |

|

|

50' 14" |

|

| -

Prologendum: Dominus regnavit |

Ps.

92 (93), 1 |

2' 01" |

|

A1

|

| -

Tractus: Vide, Domine, et considera |

Lamentationes

Ieremiase; Thren. 1. 11 c. 9 c

(Feria III. post Dominicam IV. in

Quadragesima) |

0' 41" |

|

A2

|

| -

Lauda (post Evangelium): Laudate

Dominum, quoniam bonus est psalmus |

Ps.

146 (147), 1. 7 (Feria III. post

"Carnes tollendas") |

0' 53" |

|

A3 |

| -

Preces: Ecclesiam sanctiam

catholicam |

ex

Missa Sancti Iacobi |

1' 02" |

|

A4 |

| -

Nomina offertorium: Per

misericordiam tuam, Deus noster |

ex

Missa Sancti Iacobi |

3' 57" |

|

A5 |

| -

Antiphon: Pacem meam do vobis |

Jo.

14, 27; 13, 34 |

2' 09" |

|

A6 |

| -

Illatio: Introibo ad altare Dei mei |

Ps.

42 (43), 4 (In Festo Sancti Iacobi) |

5' 00" |

|

A7 |

| -

Sanctus |

Jes.

6, 3 |

0' 45" |

|

A8 |

| -

Post Sanctus: Vere sanctus, vere

benedictus |

ex

Missa Sancti Iacobi |

1' 39" |

|

A9 |

| -

Credo |

|

3' 40" |

|

A10 |

| -

Pater noster |

|

1' 28" |

|

A11 |

| -

Ad confractionem panis: Gustate et

videte |

Ps.

33 (34), 9 (8). 2 (1). 23 |

1' 58" |

|

A12 |

| -

Kyrie I |

|

2' 10" |

|

B1 |

| -

Kyrie II |

|

2' 41" |

|

B2 |

| -

Kyrie III |

|

1' 21" |

|

B3 |

| -

Gloria |

|

2' 59" |

|

B4 |

| -

Sacrificium: Offerte Domino |

ex

Missa Feria III. post "Carnes

tollendas" (per totam Quadragesimam) |

1' 37" |

|

B5 |

| -

Sanctus |

|

1' 30" |

|

B6 |

| -

Agnus I |

|

2' 30" |

|

B7 |

| -

Agnus II |

|

1' 15" |

|

B8 |

| -

Antiphon (Lauda): Statuit Dominus |

In

festo S. Mercii Evangelistae |

2' 47" |

|

B9 |

| -

Lamentatio Ieremiae Prophetae:

Aleph. Ego vir videns |

Feria

VI. in Parasceve |

5' 00" |

|

B10 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sources:

Kyriale Hispanicum, ed. G. Prado.

Paris/Tournai/Rom 1934 (Desclée

& Socii)

Cantus Lamentationum pro ultimo

triduo Hebdomadae majoris juxta

Hispanos Codices, ed. G. Prado.

Paris/Tournai/Rom 1934 (Desclée

& Socii)

C. Rojo u G. Prado: El canto

mozárabe, Estudio histórico...,

Barcelona 1929 (Diputación

Provincial de Barcelona)

Missale mixtum secundum regulam

beati Isidori (1500), ed. J.-P.

Migne, Patrologia Latina 85 |

|

|

|

| CORO DE MONJES DE

LA ABADIA DE SANTO DOMINGO DE

SILOS |

| Dom Ismael

Fernández de la Cuersta, Leitung |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Abadía

De Santo Domingo de Silos, Burgos

(Spagna) - 7/12 ottobre 1968 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Production |

|

Harald

Baudis |

|

|

Recording

supervision |

|

Harald

Baudis |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

ARCHIV

- 2533 163 - (1 LP - durata 50'

14") - (p) 1974 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

ARCHIV

- 435 032-2 - (4 CD's - durata 78'

14"; 73' 13"; 71' 18" & 73'

54" - [CD3 18-29; CD4 1-10]) - (c)

1993 - ADD

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Ms.

London, British Museum, Add. 30

845 (10. Jh.), fol. 144'/45. 36,5

cm x 26,4 cm.

Altspanische Liturgie: Officium

in diem Sancti [Ae]miliani ad

Vesperas.

(Benediktinerkloster San Millán de

la Cogolla, Altkastilien)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The Tradition of

the Gregorian Chant (III)

Santo Domingo

de Silos - Ancient Spanish

Chants from Ordinarium and

Proprium missae

Before the final acceptance of

the Roman Gregorian form as the

sole liturgy of the entire

Church about the eleventh

century, numerous liturgies were

in use in various parts of the

Latin West, each of them

influenced by the ethnic

characteristics of a particular

race and its social structure:

the ancient Gallican liturgy as

a rite of the State religion of

Merovingian France, the

Irish-Celtic rite of the

numerous monasteries in the

Emerald Isle, that of Milan -

for centuries the most important

of Italian cities -, the court

ceremonial of the southern

Italian dukedoms, the two rites

of the Roman liturgy, and

finally that of the Iberian

Peninsula, which is especially

interesting on account of its

colourful nature and the

distinctive stamp given to it by

the national character.

This liturgy attained its

highest fulfilment during the

7th century in what was then the

kingdom of the Visigoths

(Western Goths) which had Toledo

as its capital, both as a

political and religious centre.

The renowned polyhistor Isidore

of Seville (died 639) was less

concerned with the evolution of

this liturgy than the three

great princes of the Church at

Toledo and poet-musicians, the

highborn Visigoth Eugene III and

his successors Ildefons and

Julian. Soon afterwards (711)

the Visigothic kingdom was

destroyed by the Arabs, but the

Moorish domination of large

areas of Spain, which lasted for

seven centuries, brought about

no decisive changes in matters

of religious observance and

ritual. In general Christians

were not greatly hindered in the

practice of their religion. They

were even known as Arabs or

Mozarabs, i.e. false Arabs, and

their Visigothic ritual as

Mozarabic.

The situation changed only when,

after about the beginning of the

11th century, with the gradual

reconquest of the Peninsula, the

ancient Visigothic-Mozarabic

liturgy and its chants, which

had remained untouched under the

Moorish regime, were gradually

replaced by the liturgy of the

Roman Papacy. We must therefore

distinguish between two

liturgics: the ancient Spanish

liturgy, known as Mozarabic, of

the Visigoths (record side 1),

and the liturgy of the Roman

Papacy which from about 1050

onward gradually came into use

throughout Spain (record side

2).

We possess numerous documents of

the former, the genuine ancient

Spanish liturgy and its chants.

One example is shown in the

cover illustration, taken from a

10th-century manuscript from the

Benedictine monastery of San

Millán de la Cogolla in Old

Castile (now in London, British

Museum, Add. 30845); in the

left-hand margin a typical

melody to the second syllable of

(all-)le(-luia)

winds its way upwards - there

are perhaps 175 notes -, an

example of ancient Spanish

delight in melody. In the next

column there begin the prayers

and hymns for the feast of the

monastery’s patron saint, a

stylized portrait of whom is

shown, the OFFICIUM IN

DIEM/SANCTI [AE]MILIANI (the

Spanish San Millán) AD VESPERAS;

after the introductory chant the

sono (the vernacular form

of sonus) begins in the

penultimate line, and several

antiphons follow on the

right-hand side. The text is in

the ancient Visigothic script,

and the musical notation is in

the form of neumes, which

indicate only the direction

taken by the melodic line, not -

a very regrettable fact for us

today, as we do not know the

melodies of which this notation

was intended merely as a

reminder - the exact intervals.

Unfortunately the ancient

Spanish neumes were not

transferred to notation on

lines, enabling us to read the

melodies precisely, as occurred

throughout the rest of Western

Europe about the year 1050. Thus

the whole melodic treasury of

ancient Spain remains a closed

book, one of the most

regrettable losses in the whole

of musical history. Not all is

lost, however. Archbishop

Ximenes of Toledo, “one of the

greatest national personalities

of Spain” (died 1517) preserved

what had survived through

word-of-mouth tradition, which

had been passed down with

incomparable fidelity right

through the middle ages. These

survivals were documented in two

ways: in 1500 Ximenes had the

melodic formulae for the Mass

which were sung by the priest or

in alternation with him

published (most readily

accessible in Volume 85 of

Migne’s Patrologia Latina), and

he had the actual melodies

written out in three extensive

volumes known as Cantorales,

choirbooks which are preserved

in the Capilla Mozarabica of

Toledo Cathedral. A number of

these melodies (23) were

published by the two

Benedictines from Silos, Casiano

Rojo and Germán Prado, in their

monograph which is still a

principal source of information

today.

While at least a large number of

the melodies contained in the

printed volume of 1500 may be

accepted on stylistic grounds as

being of genuinely ancient

Spanish origin, this cannot

always be assumed in the case of

chants given in the Cantorales.

It has been shown that none of

these melodies correspond to any

of the chants indicated by means

of neumes in ancient manuscripts

(although the texts are almost

identical); nevertheless it must

be said that they are full of

Mozarabic “feeling”, and that

they fit into none of the known

stylistic categories of

plainsong in existence around

1500, so that they may well be

regarded as neo-Mozarabic

melodies. Even if they are not

wholly authentic, at least some

of them may be. (There is still

scope for further research into

this subject).

These Mozarabic and

neo-Mozarabic melodies occupy

the first record side. Two of

them also appear on the second

side (Nos. 5 and 9), which is

devoted to the Mass according to

the Roman rite, predominant in

Spain from the end of the 11th

century onwards. With the coming

of the Roman Mass its principal

sections and their settings - Kyrie,

Gloria, Sanctus

and Agnus - began to

occur in large numbers in

Spanish books. Much of this

material came from neighbouring

southern France, whose system of

musical notation was employed to

an ever-increasing extent in the

Iberian Peninsula, soon becoming

the only one in use.

The twelve chants on side 1 of

this record represent various

selected portions of an ancient

Spanish Mass, as it may have

been visualized at Toledo around

1500. (1) The Mass begins with

the Prolegendum (also

known as the Praelegendum

or Officium); at its

centre a soloist sings a section

of psalmody (Induit dominus...),

whose individual verses are

introduced and concluded by the

choir in the manner of a

refrain; here and in other

similar responsorial

neo-Mozarabic chants the soloist

and choir sing the same melody,

a practice which would be

unthinkable in Roman Gregorian

chant. (2) The ancient Spanish Tractus,

with its free construction and

its F tonality (like that of the

preceding Prolegendum),

has only its name in common with

the Roman Tractus (the piece

here recorded is only the

beginning). (3) The lesson of

the Gospel was followed in the

ancient Spanish Mass by a

sometimes very extensive chant

known as Laudes (or Lauda);

the neo-Mozarabic melodies

preserved in the Cantorales of

Ximenes, including the one

recorded here, are considerably

shorter. - More probably

genuinely ancient Spanish are

the two following prayers

declaimed by the priest: (4) the

monks of Silos offer only a

short section from one of the Preces,

which were so greatly loved that

they were even copied into the

books of the ancient Gallican

Church beyond the Pyrenees; (5)

to the same melodic formula the

deacon sings the “Nomina

offerentium”, a long

enumeration and invocation of

saints, in spiritual union with

whom those present participate

in the Sacrifice

of the Mass. (6) The melody of

the antiphon Pacem meam,

sung in alternation, was at

least conceived in the archaic

spirit of ancient Spanish

plainsong. (7) Undoubtedly of

genuine ancient Spanish origin,

as is proved not only by its

length but also by its archaic

formulation, is the Illatio,

the Spanish counterpart to the

(much more concise) Roman

Preface. (8) As in the Roman

form the Spanish Illatio

leads into the Sanctus;

(9) while in Rome the

continuation is prayed silently,

in Spain it is sung to the Illatio

melody. (10) To a single note,

varied slightly only at the ends

of principal sections, all

present in the church sing the

Creed, a particularly solemn

moment in an actual service.

(11) To a formula of great

antiquity, which also survives

in the Roman liturgy (e.g. in Gloria

XV and in the 4th psalm

tone) the priest sings the

individual supplications of the

Pater noster, to each of

which the congregation here

respond with Amen, an

impressive and original manner

of presentation not known to

have existed anywhere else. (12)

The singing of Psalm 33

(Anglican Psalm 34) at the

Communion has come down to us

from the dawn of Christianity,

on account of the verse “O

taste, and see, how gracious the

Lord is”; again, it may be said

of the melody given in the

Cantorales that its

neo-Mozarabic character is

spiritually akin to that of

ancient Spanish forms.

The first of the three Kyrie

melodies at the beginning of the

Roman Mass (2nd record side,

1-3) reveals to the attentive

listener an entirely different

style, marked especially by wide

interval leaps foreign to

ancient Spanish chants. From the

9th/10th century onward

musicians in Western countries

from England to Sicily produced

many hundreds of Kyrie melodies,

a considerable number of which

found their way to Spain

following the adoption there of

the Roman rite. The three

examples recorded here, taken

from a manuscript which

originated at San Millán, are

typical of a large proportion of

all Kyrie melodies in that the

second of the three textually

identical supplications is sung

at a lower pitch than the

others; the fine balance thus

established is emphasized by

alternation between solo singer

and choir. (4) A manuscript from

the Benedictine monastery of San

Juan de la Peña on the southern

slopes of the Pyrenees (at

present in the Huesca Cathedral

Library) is the source of the

simple Gloria, centred

upon a single note. (5) The

beautiful Sacrificium

(corresponding to the Roman Offertorium),

taken from one of the

neo-Mozarabic Cantorales,

creates the atmosphere of the

ancient Spanish chants, partly

owing to the fourfold repetition

of the notes F E D at Offerte

domino (and later at Gloria

et honor). (6) The Sanctus

is sung to a melody found in

many parts of Europe, including

Northern France and Sicily. (7)

The first Agnus,

probably French in its origins,

is marked by the fact that each

of its three supplications

descends to a slightly lower

pitch. (8) The second, very

straightforward Agnus

has come down to us only in the

manuscript at Huesca mentioned

above (4), so it is likely to be

a relatively late Spanish

composition. (9) The beautiful

neo-Mozarabic piece entitled Laudes,

to the words Statuit dominus,

although it has not yet been

discovered in the earliest

sources of melodies for the

Visigothic/Mozarabic rite, is

marked by stylistic features

which suggest that it may well

be a genuine ancient Spanish

piece. (10) The origin of the

melody to which the third lesson

of the evening service on Good

Friday was chanted is uncertain;

each of its three sections,

consisting of three verses from

the Lamentations of Jeremiah, is

introduced by one of the Hebrew

letters Aleph, Beth, Ghimel (A,

B, C), also set to music, all

nine passages being sung to the

same powerfully expressive

melody.

The Abbey of Santo Domingo in

the little village of Silos,

with its famous Romanesque

cloisters, lying in isolation in

the mountains a little less than

halfway along the road from

Burgos to enchanting Soria (with

the ruins of Numantia nearby),

is one of the oldest among the

Benedictine monastic

establishments still standing in

Spain. The tradition that it was

founded during the Visigothic

era (end of the 6th century) has

been confirmed by archaeological

discoveries. In its heyday under

the great Abbot Domingo

(Dominicus, 1041-73), to whom it

owes its name, the services were

celebrated and sung according to

the ancient Spanish rite, as is

proved by the substantial number

of manuscripts which have

survived from that time (now in

London, Madrid, Paris, and at

Silos itself). The library at

Silos also contains much

important documentation of the

period following the adoption of

the Roman rite.

Bruno

Stäblein

|

|

|