|

|

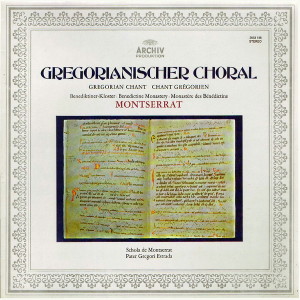

1 LP -

2533 158 - (p) 1974

|

|

| 4 CD's -

435 032-2 - (c) 1993 |

|

| THE TRADITION OF

THE GREGORIAN CHANT - (II) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MONTSERRAT

- Benedictine Monastery

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| RESPONSORIA

AD MATUTINUM IN NATIVITATE DOMINI

IUXTA RITUM MONASTICUM |

|

|

44' 00" |

|

| -

Responsorium I - Hodie nobis

caelorum rex |

Tonus

V |

6' 29" |

|

A1 |

| -

Responsorium II - Hodie nobis de

caelo pax |

Tonus

VIII |

2' 31" |

|

A2 |

| -

Responsorium III - Quem vidistis

pastores |

Tonus

IV |

2' 42" |

|

A3 |

| -

Responsorium IV - Descendit de

caelis |

Tonus

I |

4' 11" |

|

A4 |

| -

Responsorium V - O magnum mysterium |

Tonus

III |

3' 29" |

|

A5 |

| -

Responsorium VI - Beata dei genitrix |

Tonus

VII |

2' 20" |

|

A6 |

| -

Responsorium VII - Sancta et

immaculata virginitas |

Tonus

II |

2' 29" |

|

B1 |

| -

Responsorium VIII - Angelus ad

pastores ait |

Tonus

VII |

3' 29" |

|

B2 |

| -

Responsorium IX - Ecce agnus dei |

Tonus

VII |

3' 57" |

|

B3 |

| -

Responsorium X - Beata viscera |

Tonus

VII |

3' 50" |

|

B4 |

| -

Responsorium XI - In principio erat

verbum |

Tonus

VII |

3' 00" |

|

B5 |

| -

Responsorium XII - Verbum caro

factum est |

Tonus

VIII |

5' 01" |

|

B6 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Source:

Liber Responsorialis, Tournai

(Desclée) |

|

|

|

|

| SCHOLA DES

KLOSTERS MONTSERRAT |

| Pater Gregori

Estrada, Leitung |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Klosterkirche

Montserrat (Spagna) - 14/17 marzo

1973 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Production |

|

Dr.

Andreas Holschneider |

|

|

Recording

supervision |

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

ARCHIV

- 2533 158 - (1 LP - durata 44'

00") - (p) 1974 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

ARCHIV

- 435 032-2 - (4 CD's - durata 78'

14"; 73' 13"; 71' 18" & 73'

54" - [CD1 1-12]) - (c) 1993 - ADD

|

|

|

Cover |

|

MS 72

Bibliothek Montserrat, 12. Jh.,

pag. 26/27; 24,2 cm x 14,7 cm. R.

O magnum misterium etc.

(Aquitanisch-katalanische

Notation)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

The Tradition of

the Gregorian Chant (II)

Montserrat -

The Responsoria of Matins at

Christmas

The offices of the canonical

hours, sung at appointed times

throughout the day and night in

Benedictine communities, begin

at midnight with matins, at once

a highpoint of the entire cycle.

It is so not only on account of

the admirable construction of

this office and its - by

comparison with the Mass -

greater textual variety, but

also by virtue of its music; its

principal chants, the twelve

responsoria, form a particularly

impressive group within the

immense corpus of several

thousand plainsong melodies. If

these chants are to be fully

appreciated two points should be

borne in mind. Firstly, as in

the Mass the responsorial chants

regularly follow a lesson - they

are “concert pieces”, during

which the liturgical action

ceases and all present,

including the celebrant, listen

to the singing. Secondly, as its

name suggests, the responsorium

is an “answering” song. It is

centred upon the presentation of

a psalm or, as here, a freely

written text, its verses being

sung by one or more soloists to

one of the eight modal melodies

known as psalm tones, while the

choir reply with a longer

response in the nature of a

refrain. Every listener will at

once appreciate the fine effect

of the sequence, which is

clearly evident in the shaping

of its melodies: choral

responsorium - solo verse -

repetition of the choral

responsorium (although since the

beginning of written records in

the 9th century only its second

half has been repeated). There

is a third factor to be

considered: those present at

matins are aware of all the

responsoria of a festival as

parts of a larger organism,

whose structure is destroyed if

one or more sections are sung in

isolation. It is more in keeping

with the intended effect to

present in their entirety the

twelve responsorial chants for a

single festival, in this case

Christmas. (The absence of the

lesson which precedes each piece

in the liturgical context is

less important.) The texts of

the responsoria, most of which

are free prose passages of great

lyrical beauty and profundity of

ideas, throw light on the

mystery of Christmas from ever

new aspects: redemption through

the Incarnation, the shepherds,

even the ox and ass (animalia)

at the crib, the angels, the

Virgin Mother Mary, John the

Baptist who foretells the coming

of the Lamb of God, and finally

the beginning of St. John’s

Gospel telling of the Logos, the

Word become flesh - every

possible element of the story is

drawn upon so that the joy of

the festival can be savoured in

every way.

Fundamental to an understanding

of the plainsong melodies, which

are some thirteen centuries old

- recent research dates them

during the second half of the

7th century - is an appreciation

of their intimate connection

with the words. The Roman

melodies are not intended to

impart feelings so much as to

bring out the meaning of the

words, so that they will be as

understandable as possible to

the listeners. Anyone who

follows the words printed here

will be able to hear how Roman

musicians made the form of the

text both visible and audible,

because at a single vertical

stroke the rest in the melody is

shorter than at the double

stroke which occurs when the

conclusion of a particular idea

marks the end of a passage. The

function of final phrases is

emphasized by melismata, the

increased musical elaboration of

particular syllables,

represented here by slanting

print. Psalmody, i. e. the verse

melody sung by the soloist, is

always in two sections, simpler

at its centre and more richly

ornamented towards its close.

This definition of plainsong as

a means of achieving “heightened

declamation of the words” only

appears to limit its scope. It

is in fact a thing of musical

beauty such as can scarcely be

described in words. The fact

that plainsong combines these

two characteristics, faithful

service to the words and the

apparently unhindered unfolding

of beautiful melody in a manner

which may truly be described as

classical, makes it one of the

really great musical phenomena

of all times.

A few indications may make it

easier to appreciate some of the

telling effects contained in the

music. It will be noticed that

in the 1st responsorium the

first and last passages (at

“dignatus est” and to an even

greater extent at “apparuit”)

sink gracefully down from a high

level to the fundamental note.

The same striking effect occurs

in the 2nd responsorium at

“descendit” and “sunt caeli”. In

contrast to the animated melodic

line of these first two pieces,

the third, a dialogue with the

shepherds, is more tranquil.

“Descendit de caelis”, the 4th

responsorium, which follows,

concludes the first group of

four chants, the first of the

three nocturns - the principal

sections of matins. This is also

the reason why the last

responsorium of each nocturn has

a second verse, namely the

doxology “Gloria patri...”, a

last reminder of its early

version with several verses,

which has not come down to us. A

strongly expressive “O!” begins

the 5th responsorium, whose

melody is embellished with

numerous melismata emphasizing

its crucial words. In No. 6,

“Beata dei genitrix”, we again

admire the peaceful conclusion

of the two main sections. The

shorter text of No. 7, “Sancta

et immaculata”, is matched by a

less expansive and less

ornamented melody. By contrast

No. 8, “Angelus ad pastores”,

which follows, is again richer

in its musical setting; after

its rapid opening phrase the

ange1’s discourse reaches its

climax at “annuntio vobis”, then

again becoming more placid (as

in so many other instances) at

“gaudium magnum” which follows.

(The same effect occurs at “omni

populo”, “dominus” and “civitate

David”.) The first responsorium

of the third nocturn, No. 9,

“Ecce agnus dei”, a very

extensive piece, includes three

exclamations of “Ecce!” (a word

translated as “behold!”, but

this lacks the depth of meaning

of the Latin expression). The

third “Ecce!”, set to almost

thirty notes, rises to a very

high pitch, and with the “de quo

dicebam vobis” forms the climax

of the impressive, impassioned

declaration of John the Baptist.

In responsorium No. 10, “Beata

viscera”, the crucial words “Qui

hodie pro salute mundi de

virgine nasci dignatus est”, the

idea at the very heart of the

festival of Christmas, are

presented most vividly to the

listener by means of the

high-lying and richly

embellished melody. The opening

words of St. John’s Gospel are

divided between the last two

responsoria: the animated “In

principio” and the rather more

tranquil “Verbum caro”, in which

we encounter on three occasions

the already familiar and

beautiful effect of the melody

seeming to sway down to the

fundamental note (“in nobis”,

“eius” and “veritatis”); this

last responsorium is unusual in

that its versicle does not

adhere to the traditional

pattern, here of the 8th psalm

tone as used for the 2nd

responsorium; the fact that it

is, unusually, in three

sections, and its jagged,

restless line, show this new

piece of psalmody to be a later

composition.

The Benedictine monastery of

Montserrat, founded soon after

1000 A. D., which lies high in

the mountains to the west of

Barcelona, can look back on a

long and glorious musical

heritage, unequalled anywhere

else in Spain. The singing of

the present-day Escolanía

(Schola) is distinguished by its

refreshingly lively manner of

presentation, with great

rhythmical elasticity and

freedom. One can imagine that

the melodies were sung in this

manner, or something like it, in

Mediterranean countries at the

time of their composition.

The twelve responsoria are

included in the Liber

Responsorialis published by the

Benedictines of Solesmes, 1st

edition, page 56 et seq. In some

cases the monks of Montserrat

sing from better manuscript

versions, which were unknown or

had not yet found favour at

Solesmes nearly eighty years ago.

Bruno

Stäblein

|

|

|