|

|

8 LP's

- 6768 016 - (c) 1978

|

|

| 3 LP's -

6747 173 - (p) 1975 |

|

| 2 LP -

6700 116 - (p) 1977 |

|

| 1 LP -

9500 556 - (p) 1978 |

|

| 1 LP -

835 300 - (p) 1965 |

|

| 1 LP -

835 301 - (p) 1965 |

|

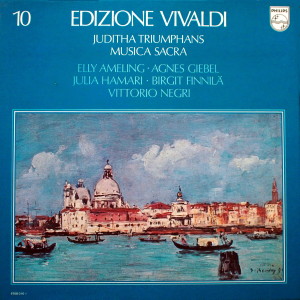

| EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing

1 - (6747 173)

|

|

49' 52" |

|

| Juditha

triumphans - Sacrum Militare

Oratorium (Cavaliere Giacomo

Cassetti) |

|

|

|

| -

Pars prior - Nr. 1-10 |

23'

37"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Pars prior - Nr. 11-19 |

26' 15" |

|

|

Long Playing

2 - (6747 173)

|

|

50' 54" |

|

| -

Pars prior - Nr. 20-27 |

19' 15" |

|

|

| -

Pars altera - Nr. 28-30a |

7' 32" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Pars altera - Nr. 30b-37 |

24' 07" |

|

|

Long Playing

3 - (6747 173)

|

|

51' 55" |

|

| -

Pars altera - Nr. 37-46 |

27' 52" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Pars altera - Nr.

47-55 |

18' 06" |

|

|

Alternative

versions:

|

|

|

|

| -

Aria (Vagaus)

"Matrona inimica" |

3' 47" |

|

|

| -

Aria (Vagaus, Coro)

"O servi volate" |

2' 10" |

|

|

Long Playing

4 - (6700 116)

|

|

47' 20" |

|

| Geistliche

Musik für Doppelchor und

Doppelorchester |

|

|

|

| - Introduzione

al Dixit G-dur

für, Sopran,

Orchester und

continuo, RV/R. 636 |

25' 38" |

|

|

|

| - Dixt

Dominus (Ps.

109, Vulgata) D-dur

für, Solisten (Zwei

Soprane, Alt, Tenor,

Baß), zwei Chöre,

zwei Orchester und

continuos, RV/R. 594 - inizio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Dixt

Dominus - fine |

11' 02" |

|

|

| - Kyrie

a 8 g-moll fur zwei

Chore, zwei

Orchester und

continuos, RV/R. 587 |

10' 40" |

|

|

| Long Playing

5 - (6700 116) |

|

46' 44" |

|

| - Beatus

vir (Ps. 111,

Vulgata) a 8 G-dur,

für Solisten (2

Soprane, Alt, Tenor,

Baß), zwei Chöre,

zwei Orcheter und

continuos, RV/R. 597

- inizio |

23' 15" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Beatus

vir - fine |

6' 28" |

|

|

| - Lauda

Jerusalem (Ps.

147, Vulgata)

e-moll, für zwei

Soprane, 2 Chöre,

zwei Orchester und

continuos, RV/R. 609 |

7' 57" |

|

|

| - Domine

ad adiuvandum me

(Ps. 69,2, Vulgata)

a 8 G-dur, für

Sopran, 2 Chöre,

zwei Orchester und

continuos, RV/R. 593 |

9' 04" |

|

|

| Long Playing

6 - (9500 556) |

|

48' 08" |

|

Motetti

a canto solo con stromenti

|

|

|

|

| - In

furore, RV/R.

626 |

12' 26" |

|

|

| - Nulla

in mundo pax,

RV/R. 630 |

12' 07" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Canta

in prato,

RV/R. 623 |

8' 06" |

|

|

| - O

qui coeli,

RV/R. 631 |

13' 29" |

|

|

| Long Playing

7 - (835 300) |

|

49' 45" |

|

| Vivaldi

in San Marco I |

|

|

|

- Gloria

D-dur, für Sopran,

Alt, Chor und

Orchester, RV/R. 589

- inizio

|

24' 41" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Gloria

- fine |

6' 13" |

|

|

| - Salve

Regina c-moll,

für Alt, ywei

Flöten,

Doppelstreichorchester

und Continuo, RV/R.

616 |

18' 51" |

|

|

| Long Playing

8 - (835 301) |

|

39' 42" |

|

| Vivaldi

in San Marco II |

|

|

|

| - Magnificat

g-moll, für Sopran,

Alt, Chor und

Orchester, RV/R. 610 |

21' 33" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Te

Deum D-dur,

RV/R. App. 38 |

18' 09" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

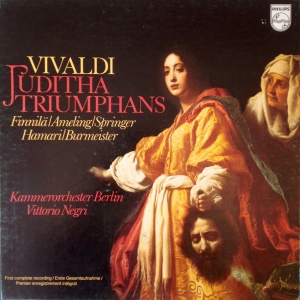

Juditha

Triumphans (6747 173)

|

Geistliche

Musik (6700 116)

|

|

| Birgit Finnilä,

Juditha (Alt) |

Margaret Marshall,

Sopran |

|

| Ingeborg Springer,

Abra (Mezzosopran) |

Ann Murray, Mezzosopran |

|

| Julia Hamari,

Holofernes (Mezzosopran) |

Anne Collins,

Alt |

|

| Elly Ameling,

Vaguas (Sopran) |

Anthony Rolfe

Johnson, Tenor |

|

| Annelies

Bourmeister, Ozias (Alt) |

Robert Holl,

Baß |

|

| RUNDFUNK-SOLISTENVEREINIGUNG

BERLIN / Dietrich Knothe, Einstudierung |

JOHN ALLDIS CHOIR |

|

| KAMMERORCHESTER

BERLIN / Vittorio Negri, Leitung |

Jeffrez Tate &

Alastair Ross, Orgel |

|

| - Helmut Pietsch, Konzertmeister |

ENGLISH CHAMBER

ORCHESTRA / Vittorio Negri, Leitung |

|

| - Peter Seydel, Viola

d'amore |

|

|

| - Roland Zimmer, Theorbe |

|

|

| - Tamara Kropat, Theorbe |

Motetti

(9500 556) |

|

| - Franz Just, Theorbe |

Elly Ameling,

Sopran |

|

| - André Pippel, Theorbe |

ENGLISH CHAMBER

ORCHESTRA / Vittorio Negri, Leitung |

|

| - Gerald Schleicher,

Salmoé |

|

|

| - Erhard Fietz, Mandoline |

|

|

| - Hans-Werner

Wätzig, Oboe |

Vivaldi

in San Marco I & II (835 300, 835

301) |

|

| - Franz Witecki, Trompete

I |

Agnes Giebel,

Sopran |

|

| - Heinz Gursch, Trompete

II |

Marga Höffgen,

Alt |

|

| - Walter Heinz

Bermstein, Orgel |

CHOR UND

ORCHESTER DES TEATRO LA FENICE, VENEDIG |

|

| - Hartmut Friedrich,

Violoncello |

Corrado Mirandola, Chordirigent |

|

| - Wilhelm Neumann, Violone |

Vittorio Negri,

Dirigent |

|

| - Jeffrey Tate, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Studio

Christuskirche, Berlin (Germania)

- maggio 1974 - (Juditha

triumphans)

Wembley Town Hall,

London (United Kingdom) -

novembre 1996 - (Geistliche

Musik)

All Hallows, Gospel Oak, London

(United Kingdom) - gennaio 1978

- (Motetti)

San

Marco, Venezia (Italia) -

ottobre 1964 - (Vivaldi in

San Marco I)

San Marco, Venezia (Italia)

- ottobre 1964 - (Vivaldi in

San Marco II)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 6747 173 - (3 LP's) - durata 49'

52" | 50' 54" | 51' 55" - (p) 1975

- Analogico - (Juditha triumphans)

Philips - 6700 116 - (2 LP's) -

durata 47' 20" | 46' 44" - (p)

1977 - Analogico - (Geistliche

Musik)

Philips - 9500 556 -

(1 LP) - durata 48' 08" - (p)

1978 - Analogico - (Motetti)

Philips - 835 300

- (1 LP) - durata 49' 45" -

(p) 1965 - Analogico -

(Vivaldi in San Marco I)

Philips - 835

301 - (1 LP) - durata

39' 42" - (p) 1965 -

Analogico - (Vivaldi in

San Marco II) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JUDITHA

TRIUMPHANS

The present recording

(based on Vivaldi’s

manuscript in possession

of the National Library

of Turin) contains the

complete music of

Vivaldi’s "Juditha

triumphans,"

including the two

alternative arias for

Nos. 5 and 21

which are included here

after the final chorus

at the end of Side 6.

The performers have

followed Vivaldi’s

musical indications even

where they differ

slightly from the order

of the text as in the

choruses Nos. 27 and 57.

Vittorio

Negri

As a composer of

instrumental music Antonio

Vivaldi needs little

introduction, for most of

his 600-odd concertos and

sonatas have been

published in modern

editions and a

representative selection

recorded. Increasingly the

attention of scholars and

performers is being drawn

to his vocal output -

operas, Cantatas, and

sacred music. For a long

time the existence of many

of these works was

unsuspected; only the

fortunate discovery in the

1920’s

of the Turin manuscripts,

several volumes of which

are devoted to Vivaldi’s

sacred and secular vocal

works, brought them to

light. Even then, their

revival was no

straightforward matter,

for the general

undervaluing of Italian

eighteenth-century vocal

music (in comparison with

that of the preceding two

centuries), the suspension

of much musical activity

during the Second World

War and, paradoxically,

Vivaldi’s very renown as

an instrumental composer

all acted as obstacles.

Although the second

Vivaldi “renaissance,”

concerned with his vocal

music, is now well under

way, as yet only the

Gloria in D has attained

the popularity of his

best-known concertos. The

oratorio “Juditha

triumphans,” a work of

somewhat different

character as it is

stylistically closer to

Vivaldi’s operas than to

the more austere

liturgical tradition with

which the Gloria maintains

strong connexions,

deserves to gain fresh

converts, for it shows the

composer at the peak of

his inventiveness.

Vivaldi is known to have

written three oratorios on

the subjects of Moses

(1714), Judith (1716), and

the Adoration of the Magi

(1722), the first two

having Latin texts and the

last a vernacular text.

Although employed at the

Ospedale della Pietà

(one of four Venetian

orphanages in which girls

received expert musical

tuition) as a violin

teacher from 1703, he

frequently deputised for

the choir master Francesco

Gasparini after the latter

went on sick leave in

1713. One of the choir

master’s tasks was to

provide music for the

frequent concerts or

services with music open

to the public held in the

Pietà’s

chapel. Oratorio was a

favourite form, for it

lent a moral purpose to

musical enjoyment,

simultaneously gratifying

the Pietà’s

pious benefactors and the

less reverent members of

the cosmopolitan audience.

Oratorio librettos - that

for “Juditha triumphans”

is by one Giacomo Cassetti

- retold biblical stories

in their own fashion,

deleting and adding

details with some freedom,

albeit with more respect

for scriptural authority

than most opera librettos

had for historical or

mythological accuracy!

The story of Judith from

the Apocrypha was a

popular oratorio subject,

perhaps because the two

central characters could

be so easily identified

with stock operatic types

- Judith herself with the

virtuous yet shrewd

heroine, and Holofernes

with the blustering tyrant

tamed by the power of

love. Cassetti severely

prunes the story by making

Ozias a high priest

instead of a governor of

Bethulia (and assigning to

him something of the

function of Joakim, the

High Priest of Jerusalem)

and by altogether omitting

Achior, the Ammonite

leader. The background to

Judith’s visit to the

Assyrian camp is provided

sketchily. In

compensation, Judith’s

maid Abra (an invented

name) and Holofernes’s

servant Bagoas (Vagaus)

assume more important

roles, becoming confidants

instead of mere

auxiliaries.

The lines beginning “Hic

decreto aeterno Veneti

maris Urbem” sung by Ozias

before the final chorus

contain an interesting

topical reference. In 1714

Venice had entered into

her sixth war with the

Turks. By equating Venice

with Judith and Turkish

might with Holofernes, Cassetti

turns the oratorio into a

prayer for victory.

Victory, alas, was not to

be, for although the

Treaty of Passarowitz

(1718) consolidated

Venetian possessions in

Dalmatia it acknowledged

the loss of virtually the

whole Peloponnese, gained

from Turkey 19 years

earlier.

At the original

performance Vivaldi’s five

vocal soloists were quite

naturally all inmates of

the Pietà.

(A female Holofernes,

Ozias, and Vagaus would

not have surprised

audiences already

accustomed to the singing

of male operatic roles by

women.) When revising the

score, possibly for a

revival, Vivaldi composed

completely new settings of

two of Vagaus’s arias,

designating them for a

“Sig.ra Barbara,” and

indicated by means of cues

the insertion of further

arias for Vagaus and Ozias

of which the music is

lost.

A four-part chorus of

mixed voices represents

Assyrian warriors and

Bethulian maidens

impartially; the tenors

and basses were possibly

recruited for the occasion

from St. Mark’s, or they

may have been drawn from

the Pieta’s teachers.

Although it includes no

instruments not found in

his concertos, the

orchestra must be one of

the largest and most

varied in composition

Vivaldi ever assembled for

a single performance.

Discounting continuo

instruments, it comprises

two trumpets with timpani,

two flauti

(modern flutes are used

here), two oboes (one as

soloist), two clarens

(either clarinets or, as

here, trumpets, the

interpretation is in

dispute), salmoé

(an obsolete woodwind

instrument whose exact

nature is still disputed),

viola d’amore, a consort

of five

viole all’inglese

(obsolete cousins of the

violin family possessing

sympathetic strings like

the viola d’amore which is

used here with three

violas, cello, and

violone), mandolin, four

theorboes (in two parts)

and solo organ, besides

the usual orchestral

strings. The number of

players is likely to have

been considerably smaller

than the number of

instruments, however, as

the same player would

double on several

instruments. From the fact

that flutes, oboes, and clarens

never play together, for

example, one may deduce

that the same pair of

players served for all

three instruments.

All Vivaldi’s choruses

save the first, a da Capo

movement, are in binary

form with instrumental ritornelli.

Except for “Vivat in

pace,” the arias follow

the da capo

pattern. Their uniformity

of construction is offset

by enormous variety of

instrumentation, key,

tempo, metre, and general

style, all these factors

contributing to the

particular affetto

(mood) of the aria and

hence to the

characterisation. The

association of instruments

or tone colours with

individual characters is

less systematic than one

is accustomed to in later

music, but its beginnings

can clearly be seen in the

reservation of the softer

and sweeter colours -

those of the salmoé

and the viola d’amore -

for Judith’s

arias. There is variety in

the recitatives too; both

Judith and Ozias have accompagnato

recitatives, and the

recitative during which Judith

beheads Holofernes

contains effective

instrumental

interjections.

The many corrections in

Vivaldi’s autograph score

(“O servi, volate” began

life as a plain continuo

aria!)

attest to the care and

imagination he brought to

the writing of “Juditha

triumphans.” Like Verdi’s

Requiem, and for similar

reasons, it deserves to be

rated as its composer’s

best opera.”

Michael

Talbot

MUSIC FOR TWO CHOIRS

AND TWO ORCHESTRAS

Since the priesthood

offered security,

education, and the

possibility of advancement

for the humble-born, it

was quite natural that

Antonio Vivaldi`s parents

had their eldest son

tonsured at the age of 15;

but either because of the

ailment (possibly asthma)

which troubled him from

birth, or his total

involvement with music, he

ceased to say Mass soon

after his ordination in

March 1703 - a lapse which

was to earn the

displeasure of the Papal

legate of Ferrara 35 years

later, when he forbade the

composer entry into that

city to direct the opera.

Vivaldi`s musical

training, centred on the

study of the violin, had a

distinctly secular bias,

so that when, in September

1703, he joined the staff

of the Ospedale della Pietà,

one of Venice`s four

"conservatoires" for

girls, his post was that

of violin master; the

composition and direction

of sacred vocal music

remained the province of

the Pietà`s

choirmaster, Francesco

Gasparini. This versatile

musician, who was one of

Venice`s most prolific and

successful composers of

opera and wrote an

important treatise on

keyboard accompaniment,

was doubtless often absent

from his duty. When King

Frederik IV

of Denmark and Norway

attended a service in the

Pietà`s

chapel in December 1708,

it was observed that the

Credo and Agnus Dei were

directed by a deputy - who

may well have been

Vivaldi.

The opportunity to compose

sacred vocal works for the

Pietà

came to him almost by

accident. In

April 1713 Gasparini

obtained sick leave and

permission to leave Venice

for a period of six

months, provided that he

continued to supply new

works for the chapel. Not

only did Gasparini

apparently fail to carry

out this task, but he

settled permanently in

Rome, where he held a

number of important posts.

His interim replacement,

Pietro Dall`Oglio, was no

composer, so Vivaldi had

to step into the breach.

The Pietà`s

maestro di coro

was required, according to

a memorandum of 1710, to

compose a minimum of two

Mass and Vespers settings

annually (one for Easter

and the other for the

feast of the Visitation of

the Blessed Virgin, to

whom the institution was

dedicated), as well as at

least two motets every

month, plus whatever

occasional compositions

might be required for

funerals, the offices

of Holy Week, etc..

Our composer matched up to

his new task so well that

on June 2, 1715 the

governors voted him a

special emolument of 50

ducats (his annual salary

was 60 ducats!)

in respect of his

provision of "a complete

Mass, a Vespers, an

oratorio [presumably the

lost ‘Moyses

Deus Pharaonis`], over 30

motets,

and others works." He

probably continued to

supply further works of

the same kind until the

appointment of Carlo

Pietro Grua as choirmaster

in February 1719.

Thereafter, his

contributions presumably

fell, as a rule, in the

interregna between the

death or departure of one

maestro di coro

and the appointment of

another; such periods lay

between March and May

1726, and September 1737

and August 1739.

As his reputation as a

composer of sacred vocal

music grew, Vivaldi

received commissions from

outside the Pietà.

It

is known, for instance,

that a lost Te Deum by him

was sung at the wedding of

Louis XV and the Polish

princess Maria Leszczyńska

in September 1725. Works

preserved in libraries

situated in present-day

Poland and Czechoslovakia

hint at commissions from

Saxony or the Empire. A

recently-discovered

inventory drawn up by the

Bohemian composer Jan

Dismas Zelenka, who must

have met Vivaldi during

his sojourn in Venice in

1716, establishes that the

latter`s Magnilicat

belonged to the Dresden

repertory.

There is also internal

evidence to suggest that

some important scores were

intended for performance

elsewhere than the Pietà.

These include the present

Beatus vir and Dixit

Dominus, both of which

allow the bass voice an

independent role,

unusually for Vivaldi`s

sacred choral works. The

identity of the tenor and

bass singers in works

composed for the Pietà

has aroused speculation.

One hynothesis

has it that male members

of the staff were drafted

into the choir -

improbable in the rigidly

stratified world of the

Pietà,

where rubbing shoulders

with one`s pupils would

surely have been

considered undignified.

Another hypothesis

proposes that choristers

were borrowed from local

churches. This is doubly

unlikely: first, because

they would have been

needed by their own choirs

on the same occasions in

the Church year; second,

because the Pietà`s

account books mention no

such arrangements. One

must therefore conclude,

if only provisionally,

that the Pietà`s

girls supplied these low

voices themselves. A list

of entrants to the coro

(this Italian word

denotes, in

eighteenth-century usage,

any large performing body,

whether made up of voices,

instruments, or both

combined) dated 1707

includes one "bass" and

three "tenors" in a

context where confusion

with instruments is

impossible. Female tenors

were not unheard of, even

as operatic singers, but

one must assume (barring

freaks of nature) that the

"basses" doubled the

instrumental bass line an

octave higher in the

manner of violins or

violas playing all'unisono

with

the cellos - incidentally,

a device of which Vivaldi

was exceptionally fond. If

this assumption is

correct, it follows that,

where there is no

instrumental bass to be

doubled by the vocal bass,

the work could not have

been performed

satisfactorily at the Pietà.

The bulk of Vivaldi`s

extant sacred vocal music

is found among the

manuscripts, largely

autograph, of the Foà

and Giordano collections

acquired by the National

Library., Turin,

in the 1920`s. Interest in

- and performance of - the

vocal works (which include

numerous operas and cantatas)

has lagged considerably

behind that of the

instrumental works, so

that up to now only a

handful - the Magnificat,

the Gloria (RV 589), and

perhaps the Stabat Mater -

have penetrated the

general repertoire. The

sacred compositions,

excluding purely

instrumental works, can be

conveniently divided into

works with liturgical and

non-liturgical (i.e.

freely-invented) texts. Into

the hrst category come five

Mass movements - and a

complete Mass (RV 586)

preserved in Warsaw - 15

Vespers psalms, nine

hymns, and a Magnificat

existing in several

versions. The second

comprises 12 motets and

eight introduzioni

(these are all works for

solo voice performed in

lieu of antiphons or

introits), plus the

oratorio “Juditha

triumphans.” This summary

excludes several works in

the Turin volumes which

were not composed by

Vivaldi, although they

seem to have once belonged

to his personal

collection.

It

is highly likely that the

extant compositions

include several designed

to form part of the same

Mass or Vespers cycle.

Although Francesco Caffi,

the nineteenth-century

historian, wrote of a

"Mass for voices and

instruments which was

repeatedly performed by

those young girls on every

great feast," no settings

by Vivaldi of the Sanctus

and Agnus Dei (discounting

those in the Mass RV 586)

have survived. It

appears, however, from

bibliographical evidence

(paper type and layout of

the score) that the less

well known of the two

Glorias (RV 588) belongs

with the Credo, RV 591.

The relationship of the

psalms and hymns is if

anything less clear. Piero

Damilano has made a

valiant attempt to

identify two cycles of

live psalms appropriate

for Vespers on the two

feasts named in the

description of the duties

of the maestro di coro,

but the reality is

obviously far more

complex. What we possess

is the fragmentary remains

of more than two such

cycles, whose original

state of completeness is

equally problematic. In

short, we know very little

about how the individual

compositions were intended

to fit

together, and any surmises

we make must be very

tentative.

The works can be

divided in two further

ways: first,

into compositions for solo

voice, for choir, and for

choir with soloists (all

with an orchestra of

strings and continuo, and

sometimes additional

instruments); second, into

"short" settings in a

single movement and "long"

settings in several

contrasted movements. The

forms

employed are what one

would expect for the

composer and period. Non-liturgical

movements for a soloist

are generally shaped as

recitatives or da capo

arias on the operatic

pattern (though the

"alleluias" concluding the

motets are

through-composed, with

strong hints of the

concerto). Liturgical

movements, the rare fugal

example excepted,

generally resemble the

outer section of a da

capo

aria, with twn principal vocal

sections framed and separated

by ritornelli; a

few accompanied

recitatives and ariosi

are also found. The

choruses in “Juditha

triumphans,”

representative of the

non-liturgical type, are

brief and dance-like as in

Vivaldi`s operas. Those in

liturgical works may be

through-composed (if

short) or fugal; the more

extended movements,

however, draw on the basic

plan of the concerto, with

its alternation between ritornello

sections, whose material

is restated in various

keys, and episodes. Where

both choir and soloists

participate in the same

movement, as in “Lauda

Jerusalem," the pattern is

more complex: the

orchestra alone has a ritornello

function, and the soloists

(with light orchestral

accompaniment) an episodic

function; but the choir

may appear in either role.

Writing for two choirs

separated spatially to

produce an antiphonal

effect originated during

the sixteenth century in

St. Mark`s, Venice - a

natural outcome of the

basilica’s possession of

two principal organs

housed in lofts some

distance apart. The

polychoral style rapidly

became a favourite means

of deploying large forces

on grand occasions, and

was practised all over

Europe, so that by the

eighteenth century one can

hardly regard it still as

characteristically

Venetian. The two (or

more) cori are

usually treated, concertato

fashion, as

opposing blocs in music of

the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries, as

represented by the

Gabrielis and Schütz.

Eighteenth-century

composers, for whom the

technique of concertato

was obsolete, tended

either to handle the

ensembles in a facile

responsorial manner,

letting one coro

take over from the other

at appropriate points

(thus the single-choir

version, RV 610, of

Vivaldi`s Magniticat could

be converted to a

double-choir work, RV 610a,

by the addition of a few

cues to the score), or to

ignore the antiphonal

element altogether and

merely take advantage of

the greater number of

available parts, as in the

final

movement of the present

Dixit Dominus.

Some writers may have

assumed too lightly that

Vivaldi`s several

compositions in due

cori were written

for St. Mark`s.

At any rate, one of them,

“Lauda Jerusalem," must

have been performed at the

Pietà,

as the four solo sopranos

- two in each coro

- are named in the

autograph score as

Margarita, Giulietta,

Fortunata, and Chiaretta.

The same girls sang in "Il

coro delle muse," a work

performed at the Pietà

on March 21, 1740

(together with

instrumental music by

Vivaldi) in honour of the

visiting Prince of Saxony.

In

an anonymous poem ofthe

late 1730`s on the subject

of the Pietà`s

female musicians,

Fortunata is described as

"young," Giulietta as "an

adolescent," and Chiaretta

as "a

girl," so "Lauda

Jerusalem" must date from

around the same time. It

should be noted that in

1723 smaller choir-stalls

were added on either side

of the main choir-stalls

in the Pietà`s

chapel, perhaps with such

works in mind.

The inclusion in this

recording of the Introduzione

al Dixit

“Canta in prato,” for solo

soprano, strings, and

continuo, is justified

by the possibility that it

was intended to precede

the present Dixit. The

keys of the two works (G

major and D major) are not

identical, as they are in

the case of the Gloria (RV

588) and its introduzione,

but they are at least

congruent. It

is amusing to see the

intrusion of Arcadian

imagery -the nightingale

(Philomela) as songster -

into a sacred work.

Listeners familiar with

Vivaldi`s Concertos "La

primavera"

(Spring) and "Il

cardellino" (The

Goldfinch) will recognise

the warbling of the

violins in the opening

aria.

The opening chorus of the

Dixit Dominus (RV 594)

reminds one through its

brilliant trumpet and oboe

writing - indeed, through

the very motives from

which it is formed - of

the better-known Gloria

(RV 589). The second

movements are also alike

in tonality (B minor) and

mood; unlike the "Et in

terra pax," however, the

“Donec ponam" makes use of

quasi-fugal imitation. Of

the remaining eight

movements of the Dixit one

may single out for mention

the "Lombardic" rhythms on

the violins in No. 4

("Tecum principium"); the

severe fugue with regular

countersubjects on the

words beginning "Tu es

sacerdos” in No. 5

("Jurabit Dominus"): the

energetic and tightly-knit

interplay of tenor and

bass soloists, in

illustration of the words

“confregit in die irae

suae reges” (He hath

broken kings in the day of

His wrath), in No. 6

("Dominus a dextris

tuis"); the rippling

triplets depicting the

brook in No. 8 ("De

torrente"); the

massiveness and floridity

of the concluding fugue on

“Sicut erat in principio.”

The subject of the last

movement, in long, even

notes like a cantus

firmus, could

be mistaken for a fragment

of plainsong; in fact, it

reproduces the shape of a

motive much used as a

ground bass, especially in

chaconnes, in Vivaldi`s

day. The motive appears

with this function in at

least three concertos (RV

107, 114, and 583), one

aria (from

“L”incoronazione di

Dario"), and one chorus

(from "Giustino") by

Vivaldi; it also underpins

the first

eight bars of J.S. Bach`s

“Goldberg” Variations and

is employed as a fugue

subject in the last

movement of the sonata in

François

Couperin`s sonata-suite

"La françoise."

Both “Kyrie eleison”

movements of the powerful

Kyrie RV 587 (the hrst

much condensed and the

second minus its

introduction) were

appropriated, in a

paraphrase for strings,

for Vivaldi`s "Concerto madrigalesco,"

RV 129 (which borrows

another movement from the

Magnilicat!).

To complicate matters, the

Magnilicat shares, as does

in part the "Et incarnatus

est" of the Credo RV 591,

the boldly chromatic

opening sequence of

chords. Clearly, this was

a passage of which Vivaldi

was fond. The second

"Kyrie eleison," in which

the two cori

remain in unison, is a

particularly good example

of a vocal fugue with non

-obbligato

instrumental doubling.

An interesting feature of

Vivaldi`s "long" setting

(there is also a

one-movement setting, RV

598) of the Beatus vir is

the use as a refrain,

repeated live times

between movements, of a five-bar

strain sung twice

(successively to the first

and second lines of text)

extracted from the opening

movement. The nine

movements are particularly

well contrasted: “Potens

in terra" (No. 2) creates

unusual sonorities through

being a "double" unison

setting; “Exortum est in

tenebris" achieves a fine

climax by combining

towards its end the two

principal ("exortum" and "misericors")

motives; "Jucundus

homo" offers a rare

example in Vivaldi`s music

of a solo organ part; "In

memoria aeterna," a tender

terzetto, reveals

his flair (little

suspected by those brought

up on old histories of

music) for imitative and

fugal writing; "Peccator

videbit" is an imaginative

and ingenious threefold

alternation of a Largo

and a Presto

section. The "Gloria Patri"

opens with a varied

restatement of material

from the opening movement,

as does the corresponding

section of the Dixit (and

of the Magnificat).

Vivaldi`s intention is to

lend a punning

significance to the

following words: “Sicut

erat in principio” (Thus

it was in the beginning).

Here he is a little

subtler than Bach, who in

his Magnificat

does not begin the

reference back until he

arrives at the very words

“sicut erat.”

At the climax of Vivaldi`s

concluding fugue each

voice in turn (the cori

are in unison) intones the

doxology on a monotone in

pseudo-plainsong fashion.

"Lauda Jerusalem" is a

"short" setting, conceived

as a single concerto-like

movement. The soprano

solos in each choir are

marked in the score to be

sung by two female

soloists (see above) in

unison, but in modern

performance they can be

taken most satisfactorily

by a single voice. The two

solo parts respond to one

another, but are never

heard simultaneously. This

concept of a duet as a

dialogue rather than an

ensemble is often

encountered in late

Baroque Italian

music (Pergolesi`s "Stabat

Mater," for example), and

is one of several features

betraying the late date of

this work.

Though its text is

extracted from Psalm 69, "Domine

ad adiuvandum me" is in

fact the response to the

versicle "Deus in

adiutorium intende" with

which the celebrant opens

Vespers. Vivaldi`s

three-movement setting is

as perfect a work of its

kind as he ever produced.

The

brilliant opening movement

captures the urgency

expressed by the word

"festina" (hasten). In the

"Gloria Patri" the solo

soprano gracefully threads

her way through a

closely-knit dialogue

between the two

orchestras, both without

continuo. The final

movement is an impressive

introduction and fugue unified

by its continuous quaver

bass.

Michael

Talbot

MOTETS A CANTO SOLO CON

STROMENTI

The word “motet” has been

used for several quite

different kinds of vocal

composition during its 700

years of existence.

Originally, a motet (the

term is a diminutive of

the French word “mot”) was

a vocal composition based

on a Gregorian cantus

firmus,

in which each of the two

or more added parts had

its own text, sometimes a

vernacular or secular

text. By the fifteenth

century the classical

definition of a motet was

established: a polyphonic

setting without cantus

firmus

of a scriptural text.

During the Baroque period

two somewhat different

interpretations of the

word arose in France and

Italy. To the French of

the grand siècle

a motet could be almost

any kind of sacred vocal

composition. The Italians

reserved the term for a

setting of a

non-liturgical text

performed by a solo singer

with an orchestral

accompaniment. Quantz

(1752) defines the genre

in these words: “Nowadays,

the Italians give the name

‘motet’ to a sacred solo

cantata in Latin, which

consists of two arias and

two recitatives, finishing

with a Halleluia, and

which is commonly sung by

one of the best singers

during Mass, after the

Credo.”

The solo motet is just one

example of the trend

towards solismo in

Italian music of the early

eighteenth century. It is

the sacred counterpart of

the solo cantata with

instrumental

accompaniment, which it

closely resembles in the

layout of text and music;

the solo motet and cantata

are likewise the vocal

counterparts of the solo

concerto and sonata.

Composers favoured a

brilliant, florid style,

as observed in Mozart’s

“Exultate, jubilate” (K.

165), a late example of

the genre. To describe

such a piece as a

“concerto for voice” would

not be inapt - especially

in a case such as

Vivaldi’s, where the

omission of an

introductory recitative

produces (discounting the

Alleluia, a sort of coda)

the same fast-slow-fast

configuration found in the

concerto proper.

One place where the

singing of motets was an

established practise was

the Ospedale della Pietà

in Venice. Its maestro

di coro was

required, according to an

ordinance of 1710, to

compose at least two

motets each month. It is

not known who had the task

of supplying the texts,

which are written in a

somewhat insecure Latin

heavily influenced by

vernacular poetry both in

language and imagery.

From 1703 to 1709 and

again from 1711 to 1716

Vivaldi served the Pietà as

a violin master. It is

unlikely that he would

have embarked on sacred

vocal composition, had not

the then maestro di

coro, Francesco

Gasparini, suddenly

departed in 1713, leaving

a vacancy which was not

satisfactorily filled

until 1719. Vivaldi

stepped into the breach.

The governors of the Pietà

were well pleased with his

efforts, voting him a

special emolument in 1715

in respect of “a complete

Mass, a Vespers, an

oratorio, over 30 motets

and other compositions.”

Before long, Vivaldi won a

continent-wide reputation

for his sacred vocal

music. Works like the

present motets justify

Mattheson’s opinion of

Vivaldi as a composer with

an exceptional

understanding, for a

non-singer, of effective

vocal writing.

Michael

Talbot

VIVALDI IN SAN MARCO I

& II

When the people of

eleventh-century Venice

found themselves with a

large sum of money at

their disposal, a

chronicle of the time

tells us, the choice fell

between waging a war, or

building a new cathedral.

The Venetians decided to

build the church, and so

the present Cathedral of

St. Mark’s was begun in

1063. It was the third

church of St. Mark’s on

the site. The first, begun

in 829, was partially

destroyed by fire during a

citizens’ revolt the

following century, and the

reconstructed building

lasted less than 90 years.

The first steps to build a

church of St. Mark’s had

been taken to house the

remains of the evangelist,

smuggled out of

Alexandria. The saint had

been immediately adopted

as Protector of Venice, a

symbol of independence and

liberty for Venice in

opposition to the patron

imposed by Ravenna. This

explains why the cathedral

gradually became the

centre of the religious

and political life of the

city. The doges were

elected there: emperors

and popes met there, and

the Venetians would gather

there in the joyful

moments of victory and in

the sad hour of defeat.

Music had always played an

important part in the

city’s religious and

ceremonial political life,

so it was natural that the

focal point of Venice’s

musical development should

be St. Mark’s. From the

“Cappella”, the body of

singers and musicians

attached to the church,

there began in the

sixteenth century the

creative impulse that was

to spread throughout the

city and later carry the

fame of Venetian musicians

throughout Europe. To such

composers as Adrian

Willaert, Andrea and

Giovanni Gabrieli, Claudio

Monteverdi, and many

others must go the credit

for the extraordinary

development and

exceptionally high

standards reached by music

in Venice when Antonio

Vivaldi was born there in

1678. His father was a

well-known violinist in

the “Cappella”, and

Vivaldi, perhaps

influenced by the

Cathedral’s impressive

services and music,

eventually dedicated his

life to religion as a

priest, and to music. The

sacred texts were

certainly known to him,

but it is clear from the

way he clothed them with

music that we are dealing

with no mere superficial

knowledge, but with a

feeling for them that

could only have come

through a deep and

sincere, though perhaps

ingenuous, love for them.

All the works on Discs 7 - 8

were recorded in

St. Mark’s itself.

The

Gloria in D, RV

589, for soloists, chorus

and orchestra opens with a

short festive orchestral

introduction which

precedes and prepares for

the joyful shout from the

chorus, “Gloria, Gloria.”

The serene and happy mood

of the whole of this first

section contrasts with the

calm almost sorrowful

nature of the second in

which the chorus sings the

prayer “Et in terra pax

hominibus bonae

voluntatis” with great

depth of feeling. The

third section “Laudamus

te,” is a brilliant duet;

the soprano and contralto

soloists take it in turns

and join together in

singing the praises of

God.

The fourth section is

linked without a break to

the fifth since the next

does not permit any

interruption. In No. 4, Adagio,

the chorus makes a

crescendo on the words

“Gratias agimus tibi"

which flows over into the

strongly enunciated

“propter magnam gloriam

tuam” of the fifth

section, marked Allegro.

The following section, No.

6, “Domine Deus Rex,” is

for soprano soloist, oboe

obbligato and continuo.

This section consists of a

beautiful melody in the

rhythm of a Siciliana

which passes from the

instrument to the voice

and after a dialogue

between the two is brought

to a conclusion by the

oboe. The chorus returns

in No. 7. After eight bars

of introduction by the

orchestra alone which set

the rhythm (dotted

crotchet) of the whole

section, the contraltos

sing a strongly rhythmical

theme, which is at once

repeated by the sopranos.

After a more melodic

central part, first the

tenors, then the basses

take up the theme first

given out by the

contraltos and lead the

choral part of the section

to a conclusion that is

almost dramatic in

character. The orchestra

rounds off this section by

repeating the first eight

bars.

No. 8 is a moving

invocation made by the

contralto soloist and

chorus. It concludes with

the expression of hope

“miserere nobis.” This is

one of the most moving

parts of the Gloria. No. 9

for the chorus who, as in

the preceding section,

address the “Lamb of God

who taketh away the sins

of the world" and ask

“suscipe deprecationem

nostram” with an

insistence and in a

crescendo that make it

seem as if they wished to

turn the request into a

demand. No. 10 is a most

beautiful aria for

contralto. The

introduction and the close

of this section, which is

full of life and vitality,

are given to the orchestra

alone. With No. 11,

“Quoniam Tu solus,” we

return to the same mood

and thematic material of

the opening section,

though here it is

differently treated. The

Gloria ends with No. 12, a

fugue which is begun by

the chorus and continuo

with the orchestra soon

joining in. Later in the

section the orchestra is

given some brief solo

passages. In spite of the

use of contrapuntal

material this section is

richly expressive and

succeeds in communicating

deep feelings of faith,

certainty, and joy.

While the Gloria is one of

the better-known pieces of

Vivaldi’s church music, it

is difficult to understand

why the Salve regina

RV 616 has been so

neglected, because, apart

from the considerable

problems set by its

performance, it contains

orchestral writing of

great refinement and is

conceived as a tender and

affectionate homage to the

Mother of Jesus. It is for

contralto solo and two

string orchestras. In the

first and last section of

the work, the first

orchestra also includes

two flutes and in the

third an obbligato flute.

The first section, Andante,

has an orchestral

introduction which is

developed at some length.

The contralto’s part

alternates melodic and

florid passages and is not

free from what vein of

melancholy which is often

present in some of the

slow movements in

Vivaldi’s instrumental

music.

The second section is an Allegro

in which the two

orchestras answer one

another and blend, both

when playing alone and

when accompanying the

soloist, to produce

wonderful effects of

sonority. The second

orchestra is silent in the

Larghetto which forms the

third section. This is

begun by the obbligato

flute, accompanied by the

violins and violas of the

first orchestra. The flute

returns after the first

phrase of the contralto

and after carrying on a

dialogue with the voice

brings the section to a

close. A clever expressive

effect is obtained in this

section by the crotchet

pause which interrupts the

word “suspiramus” after

the first syllable and

makes it particularly

realistic. In No. 4,

marked Allegro ma poco,

a deeply moving melody is

given out first by the two

orchestras playing in

unison, then by the voice.

No. 5, Andante molto,

is a continuous

interweaving of the two

orchestras. The solo part

is very expressive.

In the last section, Andante,

the voice is given a very

moving melodic line, but

whereas the mood of the

previous section is tender

and affectionate, in this,

as in the opening section,

there returns that

suggestion of melancholy,

so typical of Vivaldi,

which is not sufficiently

strong to be called

sadness but which is

enough just to cloud the

serenity of the music.

Vivaldi composed two

versions of the Magnificat

in G minor (RV 610/611).

The second differs from

the first in that some of

the sections were

completely rewritten. For

this recordingl have kept

the “Sicut locutus

est” section of the first

version since I find it

more interesting than that

of the second, but

otherwise, for the rest of

the work, I have used the

definitely superior second

version.

The short opening chorus

is a magnificent example

of the use of harmony as a

means of expression. This

is followed by three

arias, the first two

(sections 2 and 3 of the

work) are for solo soprano

and the last (section 4)

for contralto solo. The

music of these three

sections keeps close to

the text in a remarkable

manner. Section 2, Allegro,

with its florid style, its

many trills and

appoggiaturas, is an

expression of exultancy.

No. 3, Andante molto,

which has an insistent

triplet figure running

throughout the movement,

sometimes passing from the

orchestra to the voice,

conveys deeply felt

emotion. The extremely

elegant Andante

which follows gives

utterance to the Virgin’s

joy and gratitude for the

predilection shown her by

God. The expressive

ascending appoggiaturas (B

natural to C) in the 34th

bar in the first violins

is a noteworthy feature of

this section.

The solo parts demonstrate

the high level of vocal

technique of the period.

The orchestral writing is

never limited to mere

accompaniment for the

voice but prepares the

mood of the piece,

intervenes and takes part

in the dialogue, and

brings it to a close. No.

5, Andante molto,

is for the chorus. After

four introductory bars

from the orchestra in

which a short theme is

given out first by one

section of the orchestra

and imitated by the others

in turn, the chorus takes

up the same musical idea,

treating it at times in

the same imitative way and

at others singing

homorhythmically. In this

section too the unusual

harmony has an important

expressive function.

No. 6, Presto and

No. 7, Allegro,

are both choral numbers.

The first is energetic and

powerful, as the text

requires; the second, in

which the chorus and

orchestra are in unison

practically throughout the

movement, is impetuous and

forceful. No. 8, Allegro,

the last solo aria of the

Magnificat, though

requiring virtuoso

technique from the

contralto soloist, is

still deeply moving, No. 9

is a brief chorus divided

into three parts: Largo

- Allegro - Adagio.

The first and the third

are homorhythmic while in

the Allegro the

themes pass from one

section of the choir to

another in a imitative

manner. No. 10, Allegro

ma poco, uses two

oboes and a bassoon, the

only time this combination

appears. The choir in this

section, consists of

sopranos, contraltos, and

basses, without the

tenors. This part of the

work makes one realise the

influence exerted by

Italian composers on

Handel. The finale is also

a chorus and like No. 9 is

divided into three parts.

The first, Largo,

and the second, Andante,

are short whereas the

third, Allegro, is

a fugato movement

developed at some length.

A part of the thematic

material heard at the

beginning of the work

returns in the Largo.

The Andante is a

short chorale in which the

noble melody is given to

the sopranos. In the Allegro

the theme is strongly

enunciated by the tenors

beneath a counter-subject

from the contraltos and it

is later taken up by all

the voices in a lively

contrapuntal construction.

The movement comes to rest

in the long notes of the

final cadence and brings

the Magnificat to its

grandiose conclusion.

We do not know if the Te

Deum, RV App. 38, is

the one performed in

Venice in September 1727

during the festivities

organised by the French

Ambassador there. The

“Mercure de France”

reported that “about eight

o’clock there took place a

very fine concert which

lasted about two hours;

the music and the Te Deum

were by the famous

composer Vivaldi.”

Certainly this is the only

Te Deum in the collection

of Vivaldi manuscripts in

the Biblioteca Nazionale

in Turin, though this is

incomplete and probably in

the hand of a copyist. I

have carefully revised and

completed the manuscript

keeping as faithfully as

possible to the spirit of

the work.

The work opens vigorously

with the basses

alternating whith two

trumpets playing over

cellos, double-basses, and

continuo. When the basses

have stated that all

heavenly beings praise

God, the whole chorus

intervenes to sing three

times the word “Sanctus.”

No. 2, "Tu

Rex gloriae," is a

beautiful aria for soprano

solo and continuo with an

oboe occasionally

answering the voice; it is

joined without a break to

the next section, No. 3

“Judex crederis.” This is

a short but powerful

chorus accompanied by the

whole orchestra, with the

first trumpet dominating

in some points to produce

an effect of prodigious

vitality. No. 4, “Te

ergo,” is for the chorus

accompanied by continuo

alone. The interval of a

minor second returns often

in the long opening phrase

of the sopranos. It is

characteristic of the

whole section and gives it

a mood of sorrowing

insistence which finds

peace only at the finish,

two bars before the attacca

of No. 5, “Aeterna fac,”

in which the key changes

suddenly from D minor to D

major. The basses in this

section are divided into

two and are accompanied by

the lower strings and the

organ. No. 6, “Et

laudamus,” is a long

section in which the

soprano and contralto

soloists, accompanied by

the continuo, answer one

another at every new

phrase of the text, with

brief interventions from

the two oboes. No. 6 is

linked to the last

section. “In Te Domine,”

without a break. In this

section the chorus and

orchestra, which also has

two solo episodes,

interweave and develop

their themes in an austere

fugato style until the

climax of the “non

confundar in aeternum” is

reached.

Though very different in

character the Magnificat

and the Te Deum are

equally successful

examples of Vivaldi’s

church music and testify

to its sincerity and depth

of feeling.

Vittorio

Negri

|

|