|

|

5 LP's

- 6768 015 - (c) 1978

|

|

| 1 LP -

6500 707 - (p) 1974 |

|

| 1 LP -

6500 820 - (p) 1974 |

|

| 1 LP -

9500 044 - (p) 1976 |

|

| 1 LP -

9500 299 - (p) 1977 |

|

| 1 LP -

6500 919 - (p) 1975 |

|

| EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing

1 - (6500 707)

|

|

52' 27" |

|

| Flute Concertos |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto G-dur für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 436 (P. 140) |

10' 53"

|

|

|

| -

Concerto D-dur für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 427 (P. 203) |

10' 37" |

|

|

-

Concerto a-moll für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 440 (P. 80) - inizio

(Allegro non troppo)

|

4' 07" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 440 (P. 80) - fine

(Larghetto · Allegro) |

6' 41" |

|

|

-

Concerto g-moll für Flöte, Fagott,

Streicher und Continuo "La notte",

RV/R. 439 (P. 342) - op. 10/2

|

10' 24" |

|

|

| -

Concerto D-dur für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 429 (P. 205) |

9' 45" |

|

|

Long Playing

2 - (6500 820)

|

|

47' 14" |

|

| Flute

Concertos |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto c-moll für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 441 (P. 440) |

12' 56" |

|

|

| -

Concerto G-dur für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 438 (P. 118) |

10' 57" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto F-dur für Flöte, Oboe,

Fagott, Streicher und Continuo "La

tempesta di mare", RV/R. 433 (P.

261) |

7' 04" |

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll für Flöte, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 108 (P. 77) |

7' 58" |

|

|

| -

Concerto C-dur für zwei Flöten,

Streicher und Continuo, RV/R. 533

(P. 76) |

8' 19" |

|

|

Long Playing

3 - (9500 044)

|

|

47' 02" |

|

| 4

Oboe Concertos |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll für Oboe, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R. 463 |

9' 35" |

|

|

| -

Concerto C-dur für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 447

(P. 41) |

14' 47" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto g-moll für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 460 |

11' 46" |

|

|

| -

Concerto C-dur für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 450

(P. 50) |

10' 54" |

|

|

Long Playing

4 - (9500 299)

|

|

47' 34" |

|

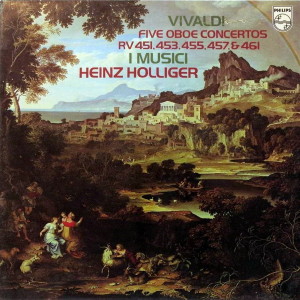

| Five

Oboe Concertos |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto C-dur für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 451

(P. 44) |

9' 04" |

|

|

| -

Concerto F-dur für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 457 |

11' 02" |

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 461

(P. 42) - inizio

(Allegro non molto) |

3' 47" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 461

(P. 42) - fine

(Larghetto · Allegro) |

6' 07" |

|

|

| -

Concerto D-dur für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 453

(P. 187) |

8' 38" |

|

|

| -

Concerto F-dur für

Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo, RV/R. 455

(P. 306) |

8' 56" |

|

|

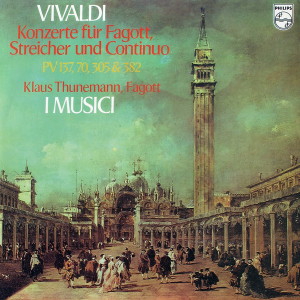

| Long Playing

5 - (6500 919) |

|

44' 42" |

|

| Konzerte

für Fagott, Streicher und Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto e-moll für

Fagott, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R.

484 (P. 137) |

11' 48" |

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll für

Fagott, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R.

498 (P. 70) |

11' 13" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto F-dur für

Fagott, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R.

489 (P. 305) |

10' 45" |

|

|

| -

Concerto B-dur für

Fagott, Streicher

und Continuo, RV/R.

502 (P. 382) |

10' 56" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

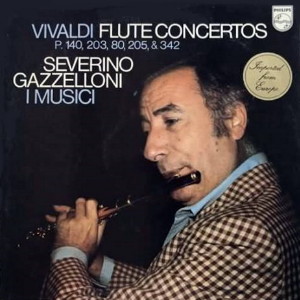

Flute Concertos

(6500 707)

|

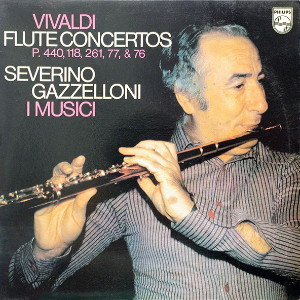

Flute

Concertos (6500 820)

|

4 Oboe

Concertos (9500 044)

|

|

| Severino

Gazzelloni, Flöte |

Severino

Gazzelloni, Flöte |

Heinz Holliger, Oboe |

|

| Jiri Staviček,

Fagott (439) |

Marja Steinberg,

2 Flöte (533) |

I MUSICI |

|

| I MUSICI |

Bernard Schenkel,

Oboe (433) |

|

|

|

Jiri Staviček,

Fagott (433) |

|

|

|

I MUSICI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Five

Oboe Concertos (9500 299)

|

Konzerte

für Fagott (6500 919) |

|

|

| Heinz Holliger,

Oboe |

Klaus Thunemann,

Fagott |

|

|

| I MUSICI |

I MUSICI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

La

Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) - luglio

1973 (Flute Concertos [6500 707])

La Chaux-de-Fonds

(Svizzera) - settembre 1973

(Flute Concertos [6500 820])

La

Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) -

luglio 1975 (4 Oboe Concertos)

La

Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) -

settembre 1976 (Five Oboe

Concertos)

La

Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera)

- settembre 1974 (Konzerte

für Fagott)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 6500 707 - (1 LP) - durata 52'

27" - (p) 1974 - Analogico -

(Flute Concertos [6500 707])

Philips - 6500 280 - (1 LP) -

durata 47' 14" - (p) 1974 -

Analogico - (Flute Concertos [6500

820])

Philips - 9500 044 -

(1 LP) - durata 47' 02" - (p)

1976 - Analogico - (4 Oboe

Concertos)

Philips - 9500 299

- (1 LP) - durata 47' 34" -

(p) 1977 - Analogico - (Five

Oboe Concertos)

Philips - 6500

919 - (1 LP) - durata

44' 42" - (p) 1975 -

Analogico - (Konzerte

für Fagott)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FLUTE

CONCERTOS

The great musical

revolutions have tended to

occur every three hundred

years. The major figures

in these revolutions have

seen themselves as

innovators and have

expressly set as their

goal the creation of a

wholly new and different

type of music. In a

treatise which appeared in

France in 1320 and was

entitled “Ars nova,” this

latter term is assigned to

that refined music which,

in its perfect combination

of multi-part composition

and lyric poetry, raised

music for the first time

to the level of a free,

autonomous art. Soon after

1600 the Florentine

composer Giulio Caccini

gave the title “Nuove

Musiche” to his volume of

solo vocal music with

keyboard or lute

accompaniment. Thus the

Baroque era was introduced

by a new lyrical art as

well as by the new

dramatic art of opera. And

finally, immediately after

the First World War, there

came to the fore in

Central Europe that

progressive form of

composition which

signalled the imminent

demise of late

Romanticism, with its

dissolution of tonality;

this was expressly

proclaimed as “New Music.”

The revolutionaries are

followed by the great

masters who put their

creative stamp upon what

has been delivered into

their hands by the

“inventors” and theorists

of “New Music.” Antonio

Vivaldi was a child of

such an inventive century

(the seventeenth);

in his works, stamped with

the seal of creative

greatness and

craftsmanlike mastery,

lies the grandiose

confirmation and

justification of all the

foregoing revolutionary

tumult, which had

completely changed the

face of music as it had

been known up to that

time. In the century

before Vivaldi, music had

still derived its strength

from an indissoluble union

between singer and player,

a marriage which could not

have been broken without

losses being sustained.

Vivaldi was the first

composer to bring about an

indisputable emancipation

of pure instrumental

music, creating a music

which only follows its own

laws and even claims

superiority to vocal

music. The former thus

attains a new and central

musical status. This was a

decisive move on Vivaldi’s

part, a move of greatest

consequence and it

received its triumphant

justification in the works

of Bach, Handel, and the

Viennese Classicists. It

was only in the

instrumental works of

Vivaldi that the last

echoes of so-called

Renaissance music finally

died away; a new musical

age had superseded the

last. All aspects of

Vivaldi’s instrumental

music also symbolise and

provide striking evidence

of the social changes of

the age. Seldom has a

whole family of

instruments been as

thoroughly eclipsed as

when Vivaldi replaced the

instruments of Renaissance

music with his own

fully-fledged Baroque

grouping. In place of a

body of sound made up of a

series of homogeneous

sound-groups, which

symbolised community, the

Baroque substituted a

grouping in which a gulf

between “ruling” and

“serving” instruments

became all too apparent.

Thus the era of musical

absolutism was ushered in.

The mass of mere

accompanying instruments

was subordinated to an

élite of instrumental

soloists.

Many instruments used in

Renaissance music now

disappeared. There were,

however, a few which

succeeded in keeping up

with and surviving the

development in solo

virtuosity. Others, which

till that point had led a

peripheral existence in

musical art, emerged from

their anonymity and set

themselves at the head of

the triumphant procession

of Baroque music. The

violin, thanks to its

high-soaring capacity, its

penetrating tone, and its

potential for virtuoso

display, assumed its now

unquestioned leading role.

For this instrument alone

Vivaldi wrote 250 solo

concertos, not least

because he himself was an

excellent violinist.

Among the brass and

woodwind it was a hitherto

little-known instrument,

the flute, which, since it

shared similar virtues to

that of the violin,

suddenly came to the fore

as a popular and admired

solo instrument. Vivaldi

wrote for the flute,

including besides duets,

11 complete concertos,

which resemble in their

architectonic structure

the three-movement violin

concertos. With regard to

their characteristic

features, however -

including the conscious

attempt to paint “sound

pictures,” - they were

wholly tailored for this

expressive instrument.

Among the flute concertos,

there is an unmistakable

“programme” work in the G minor

Concerto, “La notte,”

which by the introduction

of a bassoon and a solo

violin mysteriously evokes

the night. The climax of

this great work is an

interpolated movement, “Il

sonno” (Sleep) which, with

its restlessness, suggests

to the listener the

visions of a dream-like

state of consciousness.

In earlier epochs of

Western music, there was

no symphonic programme

music, as for example of

the kind Franz Liszt and

Richard Strauss composed,

but there existed

“pictorial” compositions.

Among roughly 450

instrumental concertos by

Vivaldi, there are no

small number, a good two

dozen in fact, whose

titles point to some

“pictorial” intention or

to that of depicting a

particular milieu. Among

them there are concertos

which, like the cycle “The

Four Seasons,” already

became famous during the

composer’s lifetime and

which, in today’s Vivaldi

renaissance, have aspired

to universal fame. Apart

from “La notte” the F

major Concerto entitled

“La tempesta di mare”

(Storm at Sea) also

belongs to these

“pictorial” works. This

piece, apart from the

occasional interpolation

of brass instruments and a

short Largo, has an

orchestral character.

Especially in the first

movement, you feel you can

hear and see the waves of

the storm-tossed sea

rising, falling, and

breaking. And even in the

Largo the unisono

of the storm breaks in

upon the peaceful episode

between the two

tempestuous movements.

Karl

Grebe

OBOE

CONCERTOS

On August 12, 1703 the

Governors of the Pio

Ospedale della Pietà,

decided to appoint

teachers of violin and

oboe on the recommendation

of the musical director.

Later that autumn Vivaldi,

newly ordained

as a priest, joined the

staff, on which he served

in various capacities

connected with the

teaching of the violin and

the direction of the

orchestra for the best

part of 40 years (with

several long breaks). Four

years later Ludwig Erdmann

was appointed as the long

overdue oboe teacher. He

stayed, however, for only

two years at the most,

departing to serve the

Grand Duke of Tuscany, and

the post fell vacant. In

June

1713 lgnazio Siber became

oboe master, but he left

in 1715 and had to be

replaced by Onofrio

Penati, a veteran of the

St. Mark’s orchestra.

Penati’s employment ceased

in 1722; possibly through

death or infirmity, and

thereafter the post was

left unfilled.

Vivaldi may well have

written his oboe concertos

(20 for one oboe, three

for two oboes, one for

oboe and bassoon, and two

for oboe and violin - not

to speak of the

instrument’s frequent

appearance in ensemble

concertos) for any of

these three men or their

best pupils. Some of the

concertos were undoubtedly

used - though not

necessarily originally

written - to fulfil

commissions from outside

the Pietà.

Because very few of

Vivaldi’s compositions can

be accurately dated, it

would be hazardous to

claim that his oboe

concertos were the first

to be written. It

is likely that the

Germans, who became

familiar with the oboe as

a vehicle of virtuosity

earlier than the Italians,

were in the field before

him. The earliest

published oboe concertos

by an Italian were the

eight in Tomaso Albinoni’s

“Concerti

a cinque,” Op. 7, which

came out in 1715. Very

soon, examples by other

Venetians such as

Alessandro Marcello and

Vivaldi himself also

appeared.

Because the oboe had not

yet fully established

itself in Italy, home of

the voice and the violin,

the style of writing for

it was often patently

modelled on a pre-existing

one: Albinoni tended to

treat the solo oboe rather

like a vocal soloist,

emphasising its cantabile

qualities; Vivaldi, as one

might expect from Europe’s

foremost violin virtuoso,

was inclined to treat it

very much like a stringed

instrument, stretching to

the utmost its capacity to

execute rapid, arpeggiated

passage-work and sometimes

leaving the player little

opportunity to draw

breath.

The forms used in

Vivaldi’s oboe concertos

do not differ from the

ones he established at the

outset of his career in

his violin concertos. The

typical form of his outer

movements is characterised

by the alternation of a

ritornello, or refrain,

scored for the full

ensemble, and various

episodes, in which the

soloist comes into

prominence. Ritornellos

are further distinguished

by relative stability of

key and a common fund of

thematic ideas, episodes

by their propensity to

modulate and the free

derivation (or invention)

of their musical material.

The Concerto in A minor,

RV 463 originated as the

bassoon concerto RV 500.

In its new guise it

retains the tutti

sections note for note,

substituting fresh solo

portions. The opening Allegro

is interesting for the way

in which it introduces ritornello

ideas into the episodes as

a background to the

soloist, a feature more

commonly found in Bach.

The finale brings a

surprise, as it does not

return to A minor but

stays in C major, the key

of the second movement.

Mistake or no, Vivaldi did

not attempt to correct it

when rescoring the work -

and with good reason, for

this finale is a strong

movement with more than a

hint of fugue.

The Concerto in C, RV 447

exists in two other

versions, one for bassoon

(RV 470) and the other

also for oboe (RV 448),

which have different

finales. The opening Allegro

non molto

exemplifies Vivaldi’s

“violinistic” treatment of

the oboe. Note also the

particularly wide

fluctuations in harmonic

rhythm (the rate of chord

change). The Larghetto

presents a cantilena

over a typically Vivaldian

accompaniment of pulsating

chords on the upper

strings; it is introduced

by a sombre ritornello,

whose last chords round

off the movement. The

finale is one of Vivaldi’s

fairly rare variation

movements, frankly

”concertante” in style.

RV 460 was published as

No. 6 of Vivaldi’s Op. 11

in 1729. It must have lain

on the composer’s shelf

for some while, as an

adaptation of it for

violin appeared as his Op.

9 No. 3 (RV 334, Ricordi

127) in 1727! G minor is

for Vivaldi a stormy key;

the feeling of

restlessness is enhanced

in the first movement by

the unusual chord (a

second inversion of the

subdominant chord) on

which the ritornello

opens. The second movement

resembles that of the

famous concerto in A minor

for two violins, Op. 3 No.

8, in being built over a

modulating ground-bass.

RV 450 is another bassoon

concerto arranged for oboe

by the composer. In the

opening Allegro molto

note the variety and

number of musical ideas.

The Larghetto, in

A minor, is conceived as a

very florid cantabile

outpouring for the oboe,

interrupted from time to

time by a short, unison

motto on the strings; the

first violin adds a few

long-breathed phrases.

Snatches of canon between

the two violins against a

buzz of repeated notes on

the viola set the tone for

the finale, a

light-hearted whirl.

The Concerto in C, RV 451

is written in a simple,

appealing style. The

ritornellos of its outer

movements both exploit one

device of which Vivaldi,

anticipating Schubert, was

especially fond: the

juxtaposition of major and

minor versions of the same

key. In

the slow movement the

ritornello is reduced to a

simple frame around an

extended solo portion.

RV 457. is an adaptation

by the composer of his

Bassoon Concerto RV 485,

whose style shows it to be

a late work. In

the first two movements

the ritornellos and, for

the most part, the

accompaniment to the solo

episodes have been taken

over as they stand, but

the finale has been

thoroughly reworked. Note

in the finale the

“masculine” opening and

the “feminine” riposte

(where the bass drops out)

- a foretaste of the

Classical style.

The first movement of RV

461 is unusual for Vivaldi

in the high degree of

thematic integration it

evinces. Much of the

melodic writing, and even

more of the accompaniment,

in the solo episodes can

be traced back to

ritornello material. The

slow movement has a simple

framing ritornello as in

RV 451. “Lombard” rhythms,

in which a long main note

is preceded by two very

short notes beginning on

the beat, are prominent in

the finale.

In RV 453 the ritornello

of the first movement

begins (disregarding a

quaver upbeat) with an

anapaestic rhythm very

frequent in Vivaldi’s

music but rare in that of

his contemporaries, and

which suggests Slavonic

folk-music. The D minor

slow movement is scored,

like that of a solo

sonata, for oboe and

continuo alone. A rhythmic

subtlety reminiscent of

the last movement of

Mozart’s Oboe Quartet

occurs in the finale:

although the metre is 12/8

alla

giga, the beats are

sometimes divided into

four instead of three in

the solo part.

The surviving manuscript

of RV 455 is non-autograph

but bears the autograph

inscription “per Sassonia”

(for Saxony, i.e. the

Dresden Court). An unusual

feature of the ritornello

of the opening movement is

the obbligato

part of the soloist, who

usually merely has to

double the first violin.

The accompaniment in all

three movements is

unusually lean, making

ample use of unisons,

while the solo writing is

lively and extrovert.

Michael

Talbot

BASSOON

CONCERTOS

Composers have been

ungenerous to the bassoon

as a solo instrument in

concertos. Mozart’s early

concerto in B flat (K.

191) is probably the only

bassoon concerto included

in the standard

repertoire. But if one

composer could make amends

for all it would be

Vivaldi. Peter Ryom lists

39 solo concertos for

bassoon - almost as many

as Vivaldi’s concertos for

all other woodwind

instruments combined! As

37 of them (the remaining

two being incomplete) have

been made available to

modern players in

Ricordi’s collected

edition we almost have an

embarras de richesse

(The Ricordi numbers of

the Concertos recorded

here are, in order of

appearance, 71, 28, 266,

and 270.)

All Vivaldi’s bassoon

concertos survive in

autograph manuscripts

contained in the volumes

of the great Foà

and Giordano collections

now housed in the

Biblioteca Nazionale,

Turin. It is believed that

these volumes are the main

repository of works

written by Vivaldi for the

Pio Ospedale della Pietà

during his long years of

service there as a violin

teacher and leader of the

orchestra (the Pietà

was an orphanage for girls

which, like three other

similar institutions in

Venice, also served as a

musical academy). Vivaldi

must have had a talented

bassoon-player

among his colleagues or

their pupils to have

endowed this instrument so

richly. The autograph

score of the Concerto in B

flat (RV 502) carries a

superscription (later

deleted) designating the

work for a certain

Giuseppe Biancardi, who is

known to have been a

member of the Venetian

instrumentalists' guild.

Another concerto (RV 496)

bears the name of Count

Morzin, the patron to whom

Vivaldi dedicated his Op.

8.

The two-keyed bassoon for

which Vivaldi wrote these

works was substantially

the same as the modern

instrument, save that its

lowest note was C instead

of B flat. His treatment

of the instrument - now

broad and lyrical, now

perkily virtuosic with

wide leaps and rapid scale

passages - owes much to

the style of his writing

for solo cello, rather as

his solo parts for flute,

recorder, and oboe

constantly recall the

violin. Nevertheless,

Vivaldi was alert to the

special needs of his

wind-players (such as

frequent opportunities to

draw breath) and skilfully

turned them to musical

advantage, as in the

“stutters” during the

second movement of RV 498.

Almost as a matter of

course Vivaldi directs his

soloists to play together

with the corresponding

orchestral part during tutti

sections, which means that

the bassoon doubles the

cellos. There was a sound

practical reason for this:

one could ill afford to

dispense with the services

of the ablest players

during the most weighty

passages! Another almost

universal practice was the

lightening of the texture

during solo episodes. At

its most economical the

accompaniment would

consist of cello and

continuo alone or (a

Vivaldian speciality) a

single line on upper

strings - unison violins,

sometimes reinforced by

violas. When

the solo instrument -

bassoon or cello - lies in

a low register the solo

instrument - bassoon or

cello - lies in a low

register one often has the

curious experience of

hearing what is

recognisably a bass line above

an obvious melody line! On

other occasions the

accompaniment may consist

of several strands and

command interest in its

own right, either through

its interplay with the

soloist or its recall of

material from the tutti

sections. Walter Kolneder

observes that the motivic

interest of the

accompaniment is

particularly marked in the

woodwind concertos and

suggests that the contrast

between wind and string

timbre encouraged the

composer to write

elaborate accompaniments

without fear of swamping

the principal instrument.

Since the same feature is

found in the cello

concertos, however,

perhaps it would be

equally correct in the

case of the bassoon

to explain it by the

contrast of register.

The form of the fast outer

movements conforms to the

usual Vivaldian pattern. A

lengthy ritornello

consisting of a number of

complementary thematic

ideas opens the movement.

It

is restated, often in

abridged or modified form,

three or four times. The

last statement is

naturally in the home key,

while intermediate

statements are normally in

different keys. Solo

episodes intervening

between the ritornellos

effect the necessary

modulations. To allow the

soloist the chance of

repeating his opening

“motto” (often a

paraphrase of a ritornello

idea) in its original key

at the head of the final

episode, the ritornello

coming immediately before

is often given out in the

home key or diverted to it

in mid-course. The final

episode frequently ends

with a brief quasi-cadenza

over a pedal point.

A simplified version of

this logical and flexible

plan is commonly employed

in the slow movements.

Sometimes all that remains

of a ritornello is a short

introduction-cum-conclusion,

as in RV 502. The slow

movement of RV 489 even

dispenses with this,

becoming almost

indistinguishable from a

sonata movement.

In these bassoon

concertos, which must be

products of his full

maturity, Vivaldi

sometimes approaches the

new galant idiom of Galuppi

and Pergolesi; one may

instance the ritornellos

in RV 489. But many

features remain uniquely

Vivaldian, such as the

rocking syncopations in

the first movement of RV

502 and the stark unisons

in the slow movement of RV

484. In the final

analysis, the most

original quality of this

music is its utter

spontaneity - its ability

to lead the listener along

unexpected paths at the

risk of occasionally

disappointing him, but

more often revealing some

rare delight.

Michael

Talbot

|

|