|

|

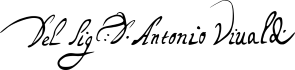

4 LP's

- 6768 013 - (c) 1978

|

|

| 2 LP's -

6747 100 - (p) 1973 |

|

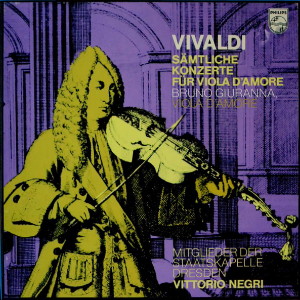

| 1 LP -

6500 242 - (p) 1971 |

|

| 1 LP -

9500 144 - (p) 1976 |

|

| EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing

1 - (6747 100)

|

|

53' 01" |

|

| Concerti für

Viola d'amore, Streicher und

Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto A-dur, RV/R. 396 (P. 233) |

11'

58"

|

|

|

| -

Concerto d-moll, RV/R. 395 (P. 287) |

15' 35" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto d-moll, RV/R. 394 (P. 288) |

14' 42" |

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll, RV/R. 397 (P. 37) |

10' 46" |

|

|

Long Playing

2 - (6747 100)

|

|

43' 50" |

|

| -

Concerto D-dur, RV/R. 392 (P. 166) |

11' 12" |

|

|

| -

Concerto d-moll für Viola d'amore,

Laute und Streicher, RV/R. 540 (P.

266) |

11' 22" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto F-dur für Viola d'amore,

zwei Oboen, Fagott, zwei Hörner und

Continuo, RV/R. 97 (P. 286) |

11' 21" |

|

|

| -

Concerto d-moll, RV/R. 393 (P. 289) |

9' 55" |

|

|

Long Playing

3 - (6500 242)

|

|

42' 37" |

|

| Concerti

con molti stromenti |

|

|

|

-

Concerto g-moll "per l'Orchestra di

Dresda", RV/R. 577 (P. 383)

|

9' 47" |

|

|

-

Concerto C-dur "per

la Solennità di San

Lorenzo", RV/R. 556

(P. 84)

|

11' 57" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Concerto g-moll "per

S.A.R. di Sassonia",

RV/R. 576 (P. 359)

|

10' 53" |

|

|

-

Concerto C-dur "con

molti stromenti",

RV/R. 558 (P. 16)

|

10' 00" |

|

|

Long Playing

4 - (9500 144)

|

|

43' 02" |

|

| Concerti

für Violoncello, Streicher und

Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto G-dur,

RV/R. 414 (P. 118) |

11' 26" |

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll,

RV/R. 418 (P. 35) |

10' 08" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto g-moll,

RV/R. 417 (P. 369) |

9' 38" |

|

|

| -

Concerto a-moll,

RV/R. 420 (F. III

No. 21) |

11' 50" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Concerti für Viola d'amore

(6747 100)

|

Concerti

con molti stromenti (6500 242)

|

Concerti für Violoncello (9500

144)

|

|

| Bruno Giuranna,

Viola d'amore |

Reinhardt

Ulbricht, Solovioline (577,556) |

Christine

Walevska, Violoncello |

|

| Roland Zimmer,

Laute |

Arndt Schöne,

Flöte |

NIEDERLÄNDISCHS

KAMMERORCHESTER |

|

| Kurt Mahn, Manfred

Krause, Oboe |

Wilfried Gärtner,

Flöte |

Kurt

Redel, Dirigent |

|

| Günther Angerhöfer,

Barockfagott |

Kurt Mahn, Oboe

(577,566,576) |

|

|

| Peter Damm,

Siegfried Gizyki, Naturhorn |

Bernhard Mühlbach,

Oboe (577,566,576) |

|

|

| Mitglieder der

STAATSKAPELLE DRESDEN |

Wolfgang

Liebscher, Fagott (577,566,576) |

|

|

| Christiane

Jaccottet, Cembalo |

Peter Mirring,

Violine (556,576) |

|

|

| Gerhard Pluskwik, Violoncello |

Joachim Bischof,

Violoncello (556) |

|

|

| Bernd Haubold, Violone |

Rudolf Haas,

Clarino (556) |

|

|

| Vittorio Negri,

Dirigent |

Bernd Hengst,

Clarino (556) |

|

|

|

Roland Zimmer,

Theorbe (558) |

|

|

|

Franz Just, Theorbe

(558) |

|

|

|

Erhard &

Elisabeth Fietz, Mandoline (558) |

|

|

|

Manfed Weise,

Hans Tuppak, Salmò (558) |

|

|

|

Alfred Schindler,

Violino in tromba marina (558) |

|

|

|

Joachim Zindler,

Violino in tromba marina (558) |

|

|

|

Friedrich Franke,

Violino in tromba marina (558) |

|

|

|

Artur Meyer,

Violino in tromba marina (558) |

|

|

|

Mitglieder der

STAATSKAPELLE DRESDEN |

|

|

|

Hans Otto, Cembalo |

|

|

|

Christoph Albrecht,

Orgel |

|

|

|

Vittorio Negri,

Dirigent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Studio

Lukaskirche, Dresden (Germania) -

novembre/dicembre 1972 (Concerti

für Viola d'amore)

Studio Lukaskirche,

Dresden (Germania) - 1970

(Concerti per molti stromenti)

(Luogo e data non riscontrabili) -

(Concerti für Violoncello)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 6747 100 - (2 LP's) - durata 53'

01" | 43' 50" - (p) 1973 -

Analogico - (Concerti für Viola

d'amore)

Philips - 6500 242 - (1 LP) -

durata 42' 37" - (p) 1971 -

Analogico - (Concerti per molti

stromenti)

Philips - 9500 144 -

(1 LP) - durata 43' 02" - (p)

1976 - Analogico - (Concerti für

Violoncello)

|

|

|

Note |

|

Koproduktion

mit WEB Deutsche Schallplatten

Berlin, DDR/R.D.A. (LP's 1,2,3)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONCERTOS

FOR VIOLA D'AMORE

The viola d’amore has

occupied a restricted but

exclusive position in

musical history and

practice. Compared with

other string instruments

there have been relatively

few examples of the

instrument - and even

those differed from one

another. It has never

appeared collectively or

in large numbers like the

violin, viola, cello, or

double-bass. Neither its

construction nor its tone

has ever been suitable for

orchestral use; from the

first its aristocratic

character was recognised

and it was regarded as

distinctly a connoisseur’s

instrument, to be used in

solo roles and chamber

music. The Italian name

now normally used for the

instrument known in France

as “viole d’amour” and in

Germany as “Liebesgeige”

could lead to the

erroneous supposition that

it was invented by Italian

instrument-makers. The

viola d’amore, however,

was developed in England,

the classical home of the

viol, where it was at

first provisionally called

the “violet.’

In the ”Syntagma Musicum”

of 1619 Michael

Praetorius, describing the

"viola

bastarda," connects it

with the English "violet,"

and the viola d’amore may

in fact be seen as a cross

between instruments from

quite different areas of

musical culture.

Around 1600 English

merchants of the then

recently formed East India

Company, travelling in the

Far East and especially in

India, discovered

previously unknown plucked

and bowed instruments

which, in addition to the

strings which sounded when

actively set in motion in

the normal way by the

fingers or with a bow,

also had metal strings

tuned to the same pitch

which vibrated with the

other strings purely

through resonance. The

delicate silvery sound

produced by the passive

vibration of these

“sympathetic” strings had

a mysterious and ethereal

effect and so impressed

the travellers that they

brought instruments of

this type back to England

with them. There

instrument-makers set

about applying this new

and interesting principle

of aliquot strings (as

they are now called) to

the string instruments

current at that time, the

viols. Violins, which had

reached England from

Northern Italy, were also

equipped with these

aliquot strings, but it

was the viola da braccia,

in the alto register,

which was found to be most

suitable; from this

instrument the viola

d’amore may well have

developed, reaching a more

or less definitive form

from the eighteenth

century onwards. There

followed a whole series of

similar attempts, among

which only the baryton, a

bass instrument popular

with amateurs in Southern

Germany, attained more

than historical

importance, because Joseph

Haydn wrote a considerable

number of agreeable

compositions at Esterháza

for the instrument, which

had sympathetic strings

which could also be

plucked by

the thumb of the left

hand.

When viols thus acquired

metal resonating strings,

sometimes even

outnumbering the actual

bowed or plucked strings,

players and

instrument-makers were

soon tempted to depart

from the traditional

tuning in thirds and

fourths which had been so

apt for the performance of

the linear polyphonic

melodies and was still

cultivated in the English

consort music of the early

seventeenth century. The

coming of the Baroque era

brought an increasing

awareness of the

importance of the triad so

that musicians wished to

tune six active and six

sympathetic strings in

pure major or minor

chords, producing an

acoustic system enhanced

by the hypnotic tonal

effect of the sympathetic

strings. The viola

d’amore, tuned in pure

triads, opened up a whole

new technique. The use of

many strings at once and

of broken-chord

figurations provided

virtuoso effects

extensively used by

Antonio Vivaldi in eight

concertos in which the

viola d’amore is featured.

The physical possibilities

of the instrument, tuned

to the common chord of the

key of the composition in

each case, are most

successfully exploited in

these Baroque instrumental

works.

Unlike his violin

concertos, Vivaldi’s

concertos for solo viola

d’amore are subject to

limitations of key which

naturally stem from the

fact that the strings had

no fixed pitch and had to

be tuned to whichever key

was in use - which, with

twelve strings, was a

tedious business. In six

of these eight concertos,

in A major or minor, D

major or minor, or,

exceptionally, in F,

Vivaldi himself precisely

indicated the required

tuning of the strings. Scordatura

was the term used for the

retuning of a string

instrument contrary to the

norm accepted for

instruments like the

violin and its deeper

relatives, the viola and

cello. It was a fairly

common procedure in

Baroque music.

Vivaldi’s purely solo

concertos for viola

d’amore, four-part string

orchestra, and continuo

are all in three

movements; between the

vibrant outer movements

the central movements are

mainly marked Largo

and their song-like

melodies are left

exclusively to the solo

instrument. In these

middle movements the viola

d’amore is accompanied

either by a fully

written-out continuo part,

an unharmonised line for

violin and viola, or a

homophonic body of strings

scored in four parts; only

in the A minor Concerto

(RV 397) does this string

orchestra also perform an

introductory role and only

in the Largo of

the D major Concerto (RV

392) is the pure solo

framed by independent

string parts in a

polyphonic style. The

central movements are

dominated by “horizontal”

improvisation - pure

melodic expression. Only

the double-stopping in the

Andante of the A

major Concerto (RV 396)

shows Vivaldi making

limited use of the tonal

possibilities of a

six-stringed instrument

tuned to a common chord.

These possibilities are,

however, fully exploited

in many of the Allegro

movements, in which

Vivaldi uses arpeggio

figurations and chords

formed by playing several

strings at once.

This capacity for

astounding nuances of

timbre in an instrument

with a relatively small

tone is in keeping with

the concerto-grosso

structure underlying all

the outer movements of the

six purely solo concertos.

Tutti and solo

sections are carefully

proportioned and follow

each other in strict

architectural balance. The

laws of proportion govern

the alternating tutti

and solo passages in

respect of length, tonal

weight, scoring, and

thematic material.

In

the A minor Concerto (RV

397) the tutti

material bears a

monumental stamp and is

reduced to a formula of

extreme brevity, while the

solo section introduces

motives giving the solo

instrument free rein for

virtuoso development.

Although the solo writing

poses extremely intricate

problems for the viola

d’amore player, this work

shows particularly clearly

the composer’s intention

of allowing ”beginners”

who can play only the

simplest chords to

participate in the tutti

passages of a musically

worthwhile piece. One may

assume that his aims were

educational. Vivaldi, who

taught music in a girls’

orphanage in Venice,

evidently wanted to let

all his pupils, whether

new or advanced, take part

in the concerts which made

Venice so attractive to

the “tourists” of that

era. Famed for their

excellence, these concerts

were the platform for the

sensationally new form of

the Baroque instrumental

concerto. Vivaldi, the

leading violinist-composer

of his generation, may

also have played the virtuoso

solo viola d'amore

parts.

The outer movements of

the A major Concerto (RV

396) resemble those of

many violin concertos in

that the viola d'amore

makes no use of its

ability to sound on

several strings at once.

This concerto could be

played on a violin

instead, a fact

confirmed by Vivaldi's

omission of any

instructions concerning

scordatura when

he wrote this

composition out. This

interchangeability of

the concerto instrument

was typical of Baroque

music and applies also

to the D minor Concerto

(RV 394), which also

lacks any indication of

scordatura in its

heading. In

the last movement,

however, we find

double-stopping and

arpeggio figuration

which suit the chordal

tuning of the viola

d’amore better than the

violin tuned in fifths.

In the D minor Concerto

(RV 395), even if one

ignores the

characteristic tone

colour of the viola

d’amore,

interchangeability is

questionable in view of

the use in some passages

of playing techniques

exclusive to the viola

d’amore. These include

arpeggio figuration,

some striking leaps, and

the use of

double-stopping to

harmonise a continuo

part consisting only of

accompanying violins.

The same characteristic

impulse distinguished

the D minor Concerto (RV

393) even more clearly,

especially in the last

movement, where a 24-bar

pedal in the basses

gives the viola d’amore

complete freedom for a

virtuoso display of its

tonal attributes. In

the D major Concerto (RV

392) the solo instrument

not only supports the

opening tutti

with complete chords but

employs double-stopping

to interrupt the

orchestral introduction

with elegant echo

effects; the extended

solo sections present a

veritable frenzy of

figuration typical of

the instruments virtuoso

capabilities. In the

final movement the viola

d’amore reinforces the tutti

with double-stopping,

and the brilliant tonal

effect of this technique

also contributes to the

unusual fascination of

the solo passages. The

gravely beautiful A

minor Concerto (RV 397)

is particularly

appealing for its broad

melodic spans, magical

passages of

double-stopping, and,

especially in the

finale, arpeggio

figurations accessible

only to a virtuoso.

An intimate atmosphere

pervades the D minor

double concerto for

viola d’amore and lute;

the presence of the lute

precludes full-blown tutti

laid out on a large

scale and this piece is

therefore a chamber

concerto framing the

enchanting conversations

of solo instruments

concerned only with

intimacy of sound. The

heart of the composition

is the Cantabile

in which, apart from a

few soft bass notes, the

orchestra is silent. The

F major Concerto (RV 97)

is more like a sinfonia

concertante than a solo

concerto, as six solo

instruments vie with

each other above a

shared continuo part,

there being no string tutti

at all. In

this four-movement piece

the viola d’amore,

contending with two

oboes, two horns, and a

bassoon as equal

partners, sometimes

employs double-stopping

to fill out or replace

the continuo. In

the Largo the

work’s many voices are

reduced to a trio of

viola d’amore, oboe, and

bassoon; a dancing

vitality lends

fascination to the

finale. Altogether

Vivaldi’s eight widely

varied viola d’amore

concertos constitute a

whole world of music in

themselves.

Karl

Grebe

“CONCERTI

CON MOLTI STROMENTI”

The bombardment of

Dresden in 1945, stands

among the most heinous

of politically

“justified” war crimes.

Photographs taken in

1936, show that the

gardens, promenades, and

beautiful buildings on

both sides of the Elbe,

looked not merely as

they were known to

Richard Strauss but as

they were to many

previous holders of his

conductorship. The Saxon

State Opera and

Orchestra of his time

had previously been the

Royal Opera and

Orchestra, and its

conductor the Court Kapellmeister.

Wagner, Weber, Hasse,

and Schütz all

held the office of Kapellmeister

at Dresden, and Bach

sought and obtained the

title of Court Composer

and directed music

welcoming the Elector’s

visit to Leipzig, where

he was employed.

Dresden’s musical repute

has always been great -

and still is; but during

the first half of the

eighteenth century,

Saxony was a foremost

claimant among the

German States for

pre-eminence in church,

theatre, and orchestral

music.

Music linked Dresden

with Venice, one of the

few cities which

rivalled its

architectural beauty.

Schütz,

“the father of German

music,” for instance,

studied in Venice with

Giovanni Gabrieli. Most

German court orchestras

were increased late in

the seventeenth century

(after Schütz’s

death) in envy and

admiration of the French

court. The first

orchestral repertory was

of French suites or

“ouvertures,”

and at first many French

musicians were imported.

The enlarged Dresden

orchestra was trained by

the violinist Volumier;

when he died in 1728

Pisendel took over the

orchestra, accompanied

his master to Venice,

and, partly through his

discipleship of Vivaldi,

brought the Elector’s

players to their summit

of fame with the rise of

the second orchestral

repertory - concertos,

first imported from Italy

and then imitated and

excelled by Germans.

The Venetian

three-movement concerto

which conquered the

German court orchestras

after 1712 was the

parent of the classical

solo concerto. It

differed radically from

Corelli’s suite-like concerto

grosso, its

ancestor being the aria,

a concerto for voice and

orchestra. The

replacement of solo

voices by instruments

naturally arose in

Venice, that city which

had first opened public

opera theatres. Quantz,

one of many Germans who

studied and adapted the

Venetian style, wrote a

“recipe” for a concerto

mentioning two operatic

features: (1) “A

splendid opening

ritornello” comprising

contrasted ideas with

which to punctuate the

solo sections; the whole

ritornello will not

recur until the finish

unless it is also used

(as in an aria) at the

end of the exposition.

(2) “An affecting adagio.”

Quantz uses adagio

to represent all slow

middle movements. Even

if short and not

actually tragic the adagio

must be “as touching as

though it had words.”

Who composed the

prototype? Possibly

Albinoni, but Vivaldi

was the artist most

responsible for its

popularity outside

Italy. His 12 concertos

of 1712, “L’Estro

armonico," Op. 3 were

often reprinted and his

many further

publications gradually

came to include wind

instruments, solo and ripieno.

Italy was regarded as

training the finest

violinists but the

northern European

orchestras were proud of

their wind players.

Fulfilling commissions

under pressure, often

when in poor health,

Vivaldi sometimes

rearranged concertos

originally scored for

string ensemble not

merely for an orchestra

including wind

instruments but for solo

or “group” wind

instruments.

Most

of the Dresden works,

however, do happen to

include a solo violin

part for Pisendel whom

Vivaldi regarded as a

friend and fellow

composer, not simply as

his violin pupil. Six

concertos in the Dresden

Library are inscribed

“Fatto per il Signor

Pisendel.” Not all

Vivaldi’s music for

Dresden is located

there. After his death a

hoard of orchestral

parts was amassed by

Count Durazzo, a patron

of the ducal orchestra

at Turin. Durazzo’s

treasure was discovered

in our own century and

ultimately bought for

the Turin Library by the

banker Foà.

Three concertos in these

recordings were for the

Saxon players, one of

them (RV 576) being in

the Turin collection.

Interest in the Concerto

in G minor (RV 557) lies

in its interplay of

groups and textures

which must have been

arresting long before

the advent of the

neo-Classical symphony;

even at that time the

solo violin part may not

have been thought

technically exacting but

it still demands fine

artistry. It was

evidently intended to

rest during the short

slow movement, which

calls for oboe or

violin solo with a bass

marked for "solo"

bassoon. The many marked

changes of instruments

participating in the basso

continuo shows

that the composer was

concerned with colour

and an orchestra whose

members were all worth

the opportunity of

distinction within a

contrast of sonorities.

Not knowing when the

Concerto in C, RV 556

was commissioned we may

imagine it to have been

used on the feast of St.

Lawrence in the church

of that name. What

remains of its façade

suggests that it was

planned on a large scale

and probably boasted

fine music from its

scuola; but in fact it

was never completed, and

possibly Vivaldi’s music

honoured not only its

patronal festival but

the dedication of some

part of the church or

its appointments. The

“symphonic” slow

introduction and the

sumptuous scoring

suggests ceremonial

magnificence, and the

key is one of the two

commonly used for

trumpets in Italy

during the period.

The concerto was

evidently played by the

Saxon orchestra, for the

MS parts are at Dresden

and include "2 clar"

which may be interpreted

as claren

(two-key clarinets) or

as clarini

(trumpets). Franz

Giegling decides for

trumpets in the outer

movements, with

appropriate effect in a

festal work; in the

middle movement,

however, Vivaldi

requires a “clar” to

join in the bass. It is

worth noting that this

movement is not a

pathetic adagio

but that, despite its

minor key and the

indication cantabile,

it maintains the

ceremonial dignity of

the whole work.

In

the Concerto in G minor,

RV 576, a dedication to

the King of Saxony is to

be found on the Turin

MS, which has parts for

two flutes. The Dresden

copies call the work Concerto

à

10 obbligati and

include parts for two

horns but not for

flutes. Except in the

slow movement, where

only the violin solo is

eloquently lyrical and

the rest purely

accompanimental, the

leading oboe is also a

prominent soloist,

sometimes making a duo-concertante

texture with the violin.

Yet this is a “group”

rather than a solo

concerto, and we may

apply to it the comments

written about the other

G minor for Dresden.

Here again Vivaldi’s

concern for contrast

extends even to the

bass.

The list of instruments

for the Concerto in C,

RV 588 poses problems: "Concerto

con due flauti, due

tiorbe, due mandolini,

due salmò,

due violini in tromba

marina." A strong

harpsichord can

discharge the same

percussive functions as

a bass theorbo or

archlute, and easily

perform the exposed

decorative figures.

There are only few

exposed passages - i.e.

not doubling other

instruments - for the

two mandolins; but their

exact doubling of the

violins in the middle

movement has an unusual

effect not easily

produced by substitutes.

Vittorio Negri uses

basset horns for the

mysterious salmò,

which seem to have been

obsolescent reed

instruments, a

supposition borne out by

a stop of the same

designation on Italian

organs which engages

reed pipes of gentler

tone than a fagotto

stop. The interpretation

of violini in tromba

marina may allow

alternatives but the

words mean ”violins to

sound like the tromba

marina,” a late medieval

novelty with a single

string stretched over a

tapering body six feet

long. The hand lightly

touched the string

without stopping it, and

the bow played near the

point of touch to

produce only harmonics.

Possibly Vivaldi used

two of these instruments

in this concerto, but

one cannot but call the

possibility very remote!

Arthur

Hutchings

CONCERTOS

FOR CELLO

Vivaldi’s cello

concertos were almost

certainly the first of

their kind to be

written. True, the cello

appears as a solo

instrument in certain

sonatas and sinfonias of

the Bologna school in

the late seventeenth

century, these works

being the stylistic

antecedents of the

concerto. One also sees

independent cello parts

(generally elaborations

of the continuo part) in

concertos written around

1700 by such composers

as Albinoni and Torelli.

But Vivaldi seems to

have been the first

composer to place the obbligato

cello on the same

footing as the soloist

in a violin concerto and

to exploit its lyrical

potential as well as its

capacity for agile

passage-work.

It is uncertain whether

Vivaldi played the cello

himself. He was

appointed violin master

at the Ospedale della

Pietà in the

autumn of 1703. This

post very probably

entailed the teaching of

other instruments

belonging to the violin

family. From the Pietà's

records we know that

from 1704 Vivaldi was

also responsible for

teaching the viola

all’inglese (or “English

violet”), an obsolete

family of instruments

similar to the viola

d’amore, which included

a bass instrument

equivalent to the cello.

By the end of the

decade he was certainly

writing cello concertos.

One of the works on this

record (RV 420) is among

the compositions by

Vivaldi copied in Venice

during the winter of

1708-9 by the young

German musician Franz

Horneck, who was in the

service of a brother of

Count Rudolf Franz Erwin

von Schönborn,

a keen cellist. Perhaps

the Count commissioned

the works from Vivaldi,

who, we must remember,

had not yet had any

concertos published (Op.

3, “L’Estro armonico,”

came out in 1711). Some

points of style identify

RV 420 as an early work:

the derivation of the

entire musical material

from a few stereotypes, the

pulsating rhythms, and the

uniformly simple

accompaniment (on continuo

alone) to the soloist.

Most of Vivaldi’s 27

concertos for a single

cello seem, by virtue of

their style, to belong to

a somewhat later period.

During his sojourn at

Mantua (1718-20) Vivaldi

must have come across a

gifted cellist, for his

opera “Tito Manlio” (1719)

contains

an aria with an intricate

cello obbligato

which hints at possible

concertos. In

the following year the

Pietà,

with which Vivaldi still

retained links, appointed

as cello master the

Reverend Antonio Vandini.

Vandini was a celebrated

virtuoso whom Charles

Burney heard on his visit

to Padua in 1770. Burney

makes the interesting

observation that Vandini

held the bow “in the

oldfashioned way with the

hand under it” - that is,

in the manner of the bass

viol (to which some

double-bass players still

adhere today).

Vandini did not stay long

at the Pietà:

he was succeeded in 1722

by the Reverend Bernardo

Aliprandi, whose contract

was renewed annually until

1728. It

is highly likely that

Vivaldi wrote several

concertos for Vandini,

Aliprandi, and their

pupils, among which could

be RV 418, and the

possibly slightly earlier

RV 417. The first two

works offer a great

contrast in style to RV

420: Their material is

much more diversified,

particularly in regard to

rhythm and the rate of

harmonic movement, and the

accompaniment to the

soloist is less uniform.

Vivaldi often has recourse

to the bassetto, a “high”

bass part played on upper

strings an octave above

the normal pitch,

sometimes even momentarily

crossing over the solo

part. This device, which

earned ”a certain master

in ltaly" (clearly

Vivaldi) a reprimand from

C. P. E. Bach in his

treatise on keyboard

instruments, was

increasingly used by

Vivaldi in his later years

as an alternative to

continuo accompaniment. In

the slow movement of RV

414 the bass line is split

up into half-bar fragments

taken alternately by

continuo and upper strings

- an imaginative

variation. Once or twice

in RV 414 and 418 he uses

the full orchestra to

provide a rich harmonic

background to the soloist.

A relatively late date for

RV 414 is also suggested

by the existence of this

work in a version for

flute (RV 438). It

is impossible to establish

from an examination of the

two concertos which

version was composed

first, even discounting

the very real possibility

that both are independent

reworkings of a lost

concerto. Nevertheless, it

is unlikely that many

years separate the two

versions.. It is fairly

certain that Vivaldi’s

interest in the flute

dates from the late 1720's,

as the first flute obbligato

in his surviving operas

appears in “Orlando

furioso” (1727), and the

Pietà

appointed its first flute

master in 1728.

The slow movement, for

cello and continuo alone,

of RV 417, may well have

been composed originally

for a lost cello sonata,

since similar movements in

Vivaldi’s violin concertos

often turn out to have

been borrowed from violin

sonatas.

What makes the cello such

an interesting solo

instrument in Vivaldi’s

hands is the fact that it

is really two instruments

(tenor and bass) in one.

Alternation between the

two registers gives the

impression sometimes of

dialogue, at other times

of polyphony. None of

Vivaldi’s other solo parts

(except, possibly, those

for bassoon) are as

eloquent as these: it is

as if deep instruments

evoked his deepest

feelings.

Michael

Talbot

|

|