|

|

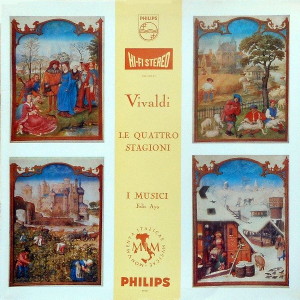

5 LP's

- 6768 011 - (c) 1978

|

|

| 2 LP's -

6700 100 - (p) 1976 |

|

| 1 LP -

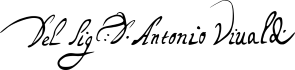

835 030 - (p) 1959 |

|

| 1 LP -

835 109 - (p) 1962 |

|

| 1 LP -

835 110 - (p) 1962 |

|

| EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

51' 53" |

|

12 Concerti für

Violine oder Oboe, Streicher und

Continuo op. 7

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 1 B-dur für Oboe, RV/R.

465 (P. 331) |

6' 35"

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 2 C-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 188 (P. 5) |

9' 13" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 3 g-moll für Violine,

RV/R. 326 (P. 332) |

8' 12" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 4 a-moll für Violine,

RV/R. 354 (P. 6) |

10' 02" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 5 F-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 285a (P. 255) |

9' 35" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 6 B-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 374 (P. 333) |

8' 16" |

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

52' 40" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 7 B-dur für Oboe, RV/R.

464 (P. 334) |

6' 45" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 8 G-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 299 (P. 102) |

7' 38" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 9 B-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 373 (P. 335) |

11' 26" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 10 F-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 294a (P. 256) |

8' 46" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 11 D-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 208a (P. 151) |

10' 50" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 12 D-dur für Violine,

RV/R. 214 (P. 152) |

7' 15" |

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

43' 58" |

|

12

Concerti für Violine, Streicher

und Continuo op. 8 "Il Cimento

dell'armonia e dell'inventione"

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 1 F-dur "La primavera",

RV/R. 269 (P. 241) |

11' 21" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 2

g-moll "L'estate",

RV/R. 315 (P. 336) |

10' 34" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 3 F-dur

"L'autunno", RV/R.

293 (P. 257) |

12' 22" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 4

f-moll "L'inverno",

RV/R. 297 (P. 442) |

9' 41" |

|

|

| Long Playing

4 |

|

37' 33" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 5

Es-dur "La tempesta

di mare", RV/R. 253

(P. 415) |

9' 12" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 6 C-dur

"Il piacere", RV/R.

180 (P. 7) |

9' 38" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 7 d-moll,

RV/R. 242 (P. 258) |

8' 21" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 8 g-moll,

RV/R. 332 (P. 337) |

10' 22" |

|

|

| Long Playing

5 |

|

41' 44" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 9 d-moll,

RV/R. 236 (P. 259) |

8' 23" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 10

B-dur "La caccia",

RV/R. 362 (P. 338) |

9' 36" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 11

D-dur, RV/R. 210 (P.

153) |

13' 24" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 12

C-dur, RV/R. 178 (P.

8) |

10' 21" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Concerti op. 7 |

Concerti op. 8

"Il Cimento dell'armonia e

dell'inventione"

|

|

| Salvatore Accardo,

Violine |

Felix Ayo, Violine |

|

| Heinz Holliger,

Oboe |

I MUSICI |

|

| I MUSICI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

La

Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) - luglio

1975 (op. 7)

Vienna (Austria) - aprile 1959

(op. 8, 1-4)

Roma (Italia) - settembre 1961

(op. 8, 5-12)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 6700 100 - (2 LP's) - durata 51'

53" | 52' 40" - (p) 1976 -

Analogico - (op. 7)

Philips - 835 030 - (1 LP) -

durata 43' 58" - (p) 1959 -

Analogico - (op. 8, 1-4)

Philips - 835 109 - (1

LP) - durata 37' 33" - (p) 1962

- Analogico - (op. 8, 5-8)

Philips - 835 110 - (1

LP) - durata 41' 44" - (p) 1962

- Analogico - (op. 8, 9-12)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leaving

aside a dozen concertos

published individually, in

all probability without

the composer’s authority,

during his lifetime and

shortly after, Vivaldi had

nine sets of concertos

engraved in Amsterdam

between 1711 and 1730.

These collections can be

divided into two groups.

The first group comprises

four sets (Op. 3, 4, 8,

and 9) dedicated to some

“person of quality” and

prefaced by a letter of

dedication. All of them

contain 12 works and have

a fanciful collective

title such as “L’Estro

armonico” or “Il Cimento

dell’armonia e

dell’invenzione.” It

is probable that Vivaldi

paid for their engraving

out of his own pocket and

trusted to the generosity

of the dedicatee for a

defrayal of his expenses.

The second group comprises

five sets (Op. 6, 7, 10,

11, and 12) with no

dedication. Except for Op.

7 they contain a mere six

works and have prosaic

titles such as “Concerti a

cinque stromenti“

(Concertos in five

instrumental parts), the

title of both Op. 6 and

Op. 7. One assumes that

the initiative for their

publication came from

Amsterdam and that the

publisher bore all the

costs, including the

composer’s payment.

Indeed, the imprint of Op.

10-12 informs us that

publication was undertaken

at the expense of Michel

Charles Le Cene, head of

the renowned Amsterdam

firm. While Op. 6 and 7,

published around 1716-17

under the name of Jeanne

Roger, Le Cène’s

predecessor, are not

explicit on this point,

they seem to conform to

the same pattern. Vivaldi

eventually found this

“commissioned” type of

publication

unsatisfactory; in 1733 he

confided to an English

visitor that he had

decided not to send any

more compositions to

Amsterdam, since published

works diminished the

market for his more

profitable trade in

manuscripts!

The distinction between

collections with and

without a dedication would

be of little consequence

if it did not explain, at

least in part, some

important musical

differences between the

works in each category.

Because the dedicated

collections were intended

to appeal to the taste of

the dedicatee as much as

to that of the general

public, they tend to

possess a consistent,

well-defined character.

Thus the works in "La

Stravaganza." Op. 4 (c.

1714), which is dedicated

to Vivaldi’s pupil Vettor

Dolfin, a Venetian noble,

are particularly

adventurous in harmony (a

quality much prized by the

Venetians), while “La

Cetra,“ Op. 9 (1727),

dedicated to Emperor

Charles VI,

cultivates an unusually

lyrical species of

virtuosity. By comparison

the works in the

undedicated sets are

disparate in character and

uneven in quality.

Vivaldi’s publisher, and

no doubt the composer

himself, knew that the

enthusiastic amateurs of

north-west Europe, who

would form a large part of

the market, would not

exercise the

connoisseurship of a

Venetian patrician or an

Austrian monarch, but

would respond favourably

to a more catholic

selection of works, from

which obvious aesthetic or

technical difficulties

were excluded.

CONCERTOS, OP. 7

Perhaps it was the

publisher who suggested to

Vivaldi that each of the

two libri

(volumes) making up Op. 7

should be headed by an

oboe concerto. In

1715 the firm of Roger had

brought out a very popular

collection of concerti

a cinque by another

Venetian, Tomaso Albinoni

(1671-1751), which

contained several oboe

concertos, at that time a

novelty in the published

repertoire. The two oboe

concertos Vivaldi included

in his own Op. 7 conform

to some extent to the

rather old-fashioned

Albinonian conception of a

concerto “with” rather

than “for” oboe, where the

wind instrument’s role is

often more one of

partnership than

dominance. Most of

Vivaldi’s oboe concertos

published subsequently, as

well as the many which

remained in manuscript,

are more straightforwardly

soloistic in character -

more akin to violin

concertos, in fact. So

perhaps these two

concertos are among

Vivaldi's earliest for

that instrument, which had

been taught since 1707 to

the girls of the Ospedale

della Pietà,

the charitable institution

with which he was closely

associated for much of his

life.

The 10 violin concertos of

Op. 7 all employ

ritornello form in their

first movements: a tutti

ritornello (or refrain)

appears at intervals in

various keys, the bridging

passages (commonly called

episodes) being given over

to the soloist. The second

movements display more

variety. Five (Nos. 3, 7,

8, 10, and 11) are in a

simple unitary

(throughcomposed) form.

Two (Nos. 4 and 9) feature

in addition a running

dialogue between soloist

and tutti, while a

further two (Nos. 1 and

12) are in a rudimentary

ritornello form. Binary

form is used in No. 2 and

also, with varied repeats,

in No. 6. The fifth

concerto has a tripartite

central movement recalling

earlier examples by

Torelli and Albinoni. The

accompaniment in solo

passages is even more

diverse. Where single-line

accompaniments are

preferred, there is a

choice between the full

string ensemble with

continuo, each instrument

playing in the appropriate

octave (No.

10), upper strings alone

(Nos. 7, 8, and 12), and

simple continuo (Nos. 1,

2, 4, 5, and 9). The slow

movement of No. 2 was

possibly borrowed from a

lost violin sonata, since

binary movements of this

type in Vivaldi’s

concertos often turn out

to be transplanted sonata

movements! An

accompaniment of two

strands (first and second

violins) is used in No.

11, and one of three

strands in No. 3 (unison

violins, viola, and bass)

and No.

6 (upper strings). The

finales are similar in

form to the first

movements, with two very

interesting exceptions.

The third concerto ends

with what may have

originated as a binary giga

in a violin sonata, for in

this movement the second

violins and violas merely

provide a harmonic

filling, while the first

violins contribute even

less, being content to

reinforce the solo

instrument on the first

note of each beat. The

ninth concerto has a

movement headed Alla

breve, an indication

that four beats are heard

in the time of a breve

rather than the more usual

semibreve. Composers of

Vivaldi’s time often

reverted to this outdated

manner of notation - as

Bach was to do in the

“Gratias agimus tibi” of

his Mass in B minor, and

Handel in the chorus “And

with his stripes” in “Messiah”

- when they wrote a

movement in an austere

contrapuntal style. But

for the presence of two

solo episodes in deference

to the concerto medium,

Vivaldi’s Alla breve

is a typical specimen. It

is, to be sure, rather

impersonal and seems to be

indebted to the music of

Bolognese composers such

as Torelli and the young

G. M. Alberti (1685-1751),

one of Vivaldi's first

Italian emulators.

Alberti’s concertos

contain several finales of

this kind, and the

comparison gains in

pertinence from the fact,

coincidental or not, that

the opening motive of the

first movement of

Vivaldi’s work is

strikingly similar to that

of the first concerto,

also in B flat, of

Alberti’s Op. 1 (1713).

The Danish scholar Peter

Ryom (from whose catalogue

of Vivaldi’s works the

numbers prefaced by “RV”

are taken) has pointed out

that four of the present

concertos (Nos. 5, 10, 11,

and 12) exist in

alternative, presumably

earlier manuscript

versions in which at least

one movement is entirely

different. Vivaldi may

indeed, as Ryom surmises,

have revised these works

on the occasion of their

publication; or what we

know as the "published"

version may have been

based on one of several

versions already in

circulation. Whatever the

chronology and function of

these alterations, we can

be sure of one thing:

Vivaldi regarded none of

the versions as a

“definitive” one to which

no further modifications

could be made. For him, as

for most of his

contemporaries, every

finished work was at the

same time potential raw

material for a future

work. How could composers

have thought and acted

otherwise when to

refurbish an old work

under the guise of a new

one was often the only way

to keep it in the

repertoire.

It

is ironic that Vivaldi

should have praised the

firm of Roger for the

accuracy of their

engraving in the preface

to his Op. 3, for they

served him badly in Op. 7.

Most of the errors are

easily spotted and

rectified (some of them

crept in when the engraver

momentarily forgot that he

had to work from right to

left on the plate to

produce a line of symbols

to be read from left to

right on the paper!) but

a few remain enigmatic.

The quality of the music,

too, sometimes falls below

the sustained level of

excellence found in Op.

3 and, especially, Op. 4.

But there is enough fine

music in the set (one

might single out the slow

movement of the third

concerto and the entire

fourth concerto) to

justify a much better

acquaintance with it.

Michael

Talbot

CONCERTOS,

OP. 8

The date of composition of

Op. 8 is not certain:

Vivaldi never dated any of

his manuscripts nor did

his publishers add a date.

In

the dedicatory letter,

which was written in 1725,

Vivaldi apologises for the

fact that Count Wenceslas

of Morzin has been

familiar with “The Four

Seasons,” the title given

to the first four

concertos of the 12, for

some time already.

Probably Op. 8 contained

concertos that were

written for different

occasions and at different

times, but all have in

common a high degree of

imagination and harmonic

skill, and in fact Vivaldi

gave this work the title

“ll Cimento dell’armonia e

dell’invenzione” (The Test

of Harmony and Invention).

The first edition appeared

in Amsterdam and was

published by Michel

Charles Le Cène

about 1725. The text of

the present recording is

based on this edition and

on that published a few

years later by Le

Clerc-Boivin in Paris,

which contains a small

number of variants.

These concertos are scored

for violin solo, first and

second violins, violas,

cellos, and continuo, and

consist of three

movements, flanked by two

quick movements. They are

true violin concertos: the

soloist is given the

opportunity in the

sections between the tutti

to display a brilliant

technique that is typical

of Vivaldi.

Each of the four concertos

of “The Four Seasons” is

preceded by a “key”

sonnet; the poet is

unknown but the poems

could easily have been

written by Vivaldi

himself. Each sonnet bears

a letter at the side of

each episode which is

repeated at the point in

the score representing the

same episode. Moreover

Vivaldi gave “a clear

explanation of all the

things represented in them

(the Seasons)” (as he

wrote to Count Morzin in

the dedication of Op. 8),

that is he added

explanatory notes to

clarify these concertos.

These works, remarkable

for the precision of the

descriptive detail, are

among the first examples

of socalled programme

music and have remained

among the greatest for the

high quality of the

musical invention, the

perfection of form, and

the delicacy of the

writing.

Of the next four

concertos, Nos. 5-8, of

Op. 8 only two bear a

title; No. 5 “La tempesta

di mare” (Storm at Sea)

and No.

6 “ll piacere” (Pleasure).

There is another concerto

by Vivaldi called “La

tempesta di mare.” This is

Concerto No, 1 in F of Op.

10, which contains six

concertos for transverse

flute, strings, and

continuo. It is

interesting to compare how

Vivaldi has treated the

same subject in these two

different works.

This is not the only point

of contact between

Vivaldi’s Op. 8 and his

Op. 10: the second

movement of Concerto l\lo.

7 of Op. 8, a Largo

in C minor, appears, in

the same key, as the

second movement of

Concerto No. 6 of Op. 10.

The fifth concerto

of Op. 8, “La tempesta di

mare,” is in E flat. The

first movement begins with

successive entries of the

first and second violins,

violas, and lower strings.

Pauseless semiquaver

figures convey very

effectively the impression

of stormy waters and the

virtuoso episodes of the

solo violin seem intended

to evoke squalls of wind.

The slow movement, a

dialogue in a rather

subdued tone between the

solo violin and the other

strings, seems like a lull

in the storm caused by the

dropping of the wind. The

respite does not last,

however. The heavily

accented notes and the

rapid descending scale

passages of the final Presto

soon recall the tempest.

The sixth concerto in C,

called "Il

piacere,” has the only

title among those given to

the concertos of Op. 8

with no descriptive

intention. The “Pleasure”

is not that of the senses

- though one cannot fail

to be struck by the great

beauty of the

orchestration - but of an

acquired state of

well-being, of serenity.

The first Allegro

flows very freely.

The episodes for the solo

violin, one of which, set

in the upper limits of the

instrument's range, is

technically very

difficult, are of the same

character. The Largo

begins with a descending

chromatic theme two bars

long announced

homophonically by all the

strings except the solo

violin. When the latter

enters with a very cantabile

melody (the indication on

the score is Vivaldi’s

own), the rest of the

orchestra accompanies it

playing in the same

rhythmic homophonic style

as the opening of the

movement. Other examples

of this method of

accompanying a solo in a

slow movement can be found

in Vivaldi and also in the

works of Albinoni and

Bonporti. The effect is of

the whole orchestra

participating in the

melody of the solo voice.

The last movement is a

strongly rhythmic Allegro.

Its theme is characterised

by widely spaced intervals

which compel the strings

to miss a string. This

leap is also found in some

of the solo episodes.

The first movement of the

seventh concerto in D

minor is very cantabile

in character. The

accompaniment to the solo

episodes is provided

sometimes by the continuo,

sometimes by the rest of

the strings holding

chords, and sometimes by

the first violins and

continuo. This subtlety

has the effect of

increasing the variety and

interest of the solo

passages. The Largo

(as already stated, this

movement appears again as

the rniddle movement of

Concerto No. 6 of Op. 10)

consists of a simple,

almost vocal, melody

entrusted to the solo

violin and supported by a

constantly moving

accompaniment of quavers

from the rest of the

strings. The last movement

has a very brilliant theme

with a constant rhythm

which returns in every tutti

passage. In

this movement the solo

violin makes frequent use

of double-stopping.

The character of the very

expressive movement which

opens the eighth concerto

in C minor is underlined

by the use of numerous

appoggiaturas. The Largo

which follows is of

outstanding beauty.

It begins with strings and

solo violin playing

together but soon the

soloist takes leave of the

orchestra and to the

accompaniment of the

continuo alone elaborates

a noble melody through

various modulations. When,

however, the original key

(B flat) is reached again,

the rest of the orchestra

joins in to finish the

movement. The final Allegro,

with its rhythmic vitality

and the brilliance of the

solo passages, forms a

fitting conclusion to the

deep spirituality of the

second movement.

On the solo part of

Concertos Nos. 9 and 12

are written the following

words: “This concerto can

also be played on the

oboe", in these two works

Vivaldi avoids his usual

style of writing for a

violin concerto so that

the music keeps within the

range and technical

possibilities of both oboe

and violin. It

is probable that this was

a concession to prevailing

taste, for at that time

the oboe was a very

popular instrument in

Venice. Vivaldi himself

wrote several concertos

for the oboe and he used

it together with other

wind instruments in

various concertos.

The first movement of the

ninth concerto in D minor

is characterised by a

syncopated figure in the

violins which is repeated

in every tutti and

which sometimes appears in

the solo episodes. The

descending chromatic

passages with which the

violins close nearly all

the tutti are very

effective. In the second

movement, for the first

time in “Il

Cimento,” the first and

second violins and violas

are silent, the sweet and

noble melody being

entrusted to the solo

violin accompanied only by

the continuo. The third

movement begins with a

remarkably brilliant

harmonic stroke: a chord

of the third and sixth on

the tonic which at once

resolves into an inversion

of the dominant and delays

for a brief instant the

affirmation of the

tonality. Here again

Vivaldi repeats the same

material, either in the

major or the minor, in

each tutti. This

common device gives the

quick movements their

sense of unity and

coherence, which is yet

further heightened by the

solo episodes, in which

thematic material is

cleverly mixed with

imaginative and virtuoso

passages.

The tenth concerto, in B

flat, is entitled “La

caccia” (The Hunt). This

is the only one in the

last group of four

concertos in Op. 8 to bear

a title. It is interesting

to note how the same

subject gives rise to the

same state of mind in the

composer. This is

especially true of the

first movement which at

once brings to mind the

other famous “Hunt” of Op.

8, viz. the third movement

of Concerto No. 3, “Autumn.”

As in the preceding

concerto the slow movement

is entrusted to the solo

violin and continuo alone.

Often the last solo

episode of the Allegro

movements gives a hint of

what the final cadence

will be, without,

nevertheless, departing

from the strict rhythmic

flow of the movement.

The first and last

movements of the eleventh

concerto in D are in fugal

style, a form not often

used by Vivaldi. In the

first movement the solo

violin, which in this

concerto has a

particularly important

role, weaves intricate

patterns as the rest of

the orchestra develops the

thematic material. In the

deeply felt Largo the solo

violin is accompanied by

the strings without the

continuo.

As in Concerto No. 9, the

solo part of the Concerto

No. 12

in C can be played either

on the oboe or on the

violin. Whereas the first

movement has a vigorous

tunefulness and the last

is richly sonorous

throughout with no

relaxation of the rhythm,

the slow movement, in C

minor, is pervaded by a

touch of melancholy which

can always be found in

Vivaldi’s work.

Vittorio

Negri

|

|