|

|

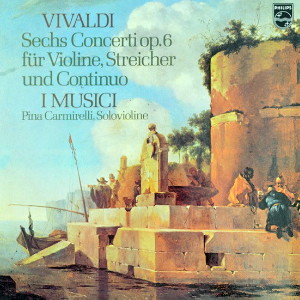

4 LP's

- 6768 010 - (c) 1978

|

|

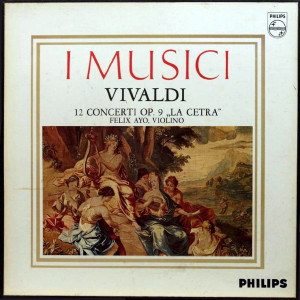

| 1 LP -

9500 438 - (p) 1978 |

|

| 3 LP's -

835 289/291 - (p) 1965 |

|

| EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

50' 01" |

|

6 Concerti für

Violine, Streicher und Continuo

op. 6

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 1 g-moll, RV/R. 327 (P.

329) |

10' 51"

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 2 Es-dur, RV/R. 259 (P.

414) |

8' 45" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 3 g-moll, RV/R. 318 (P.

330) |

7' 57" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 4 D-dur, RV/R. 216 (P.

150) |

6' 21" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 5 e-moll, RV/R. 280 (P.

101) |

7' 07" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 6 d-moll, RV/R. 239 (P.

254) |

9' 00" |

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

42' 44" |

|

| 12

Concerti für Violine, Streicher

und Continuo (Orgel) op. 9 "La

Cetra" |

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 1 C-dur, RV/R. 181a (P.

9) |

9' 40" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 2 A-dur, RV/R. 345 (P.

214) |

10' 20" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 3 g-moll, RV/R. 334 (P.

339) |

10' 39" |

|

|

| - Concerto

Nr. 4 E-dur, RV/R. 263a (P.

242) |

12' 05" |

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

41' 39" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 5 a-moll, RV/R. 358 (P.

10) |

9' 06" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 6 A-dur

(mit umgestimmter

Solovioline), RV/R.

348 (P. 215) |

13' 20" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 7 B-dur,

RV/R. 359 (P. 340) |

9' 02" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 8

d-moll, RV/R. 238

(P. 260) |

10' 11" |

|

|

| Long Playing

4 |

|

44' 14" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 9 B-dur

mit zwei obligaten

Violinen, RV/R. 530

(P. 341) |

9' 56" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 10 G-dur,

RV/R. 300 (P. 103) |

9' 55" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 11

c-moll, RV/R. 198a

(P. 154) |

10' 36" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 12

h-moll (mit

umgestimmter

Solovioline) B-dur,

RV/R. 391 (P. 154) |

13' 47" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Concerti op. 6 |

Concerti op. 9

"La Cetra"

|

|

| Pina Carmirelli,

Solovioline |

Felix Ayo, Solovioline |

|

| I MUSICI |

I MUSICI |

|

|

Anna Maria Cotogni, 2

Violine (Nr. 9) |

|

|

Anna Maria Cotogni, 2

Violine (Nr. 9) |

|

|

Maria Teresa

Garatti, Orgel (continuo) |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

La

Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) - giugno

1977 (op. 6)

La Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) -

maggio 1964 (op. 9, 1-4, 11)

La Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) -

giugno 1964 (op. 9, 5,6,7-9)

La Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) -

settembre 1964 (op. 8, 10,12) |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 9500 438 - (1 LP) - durata 50'

01" - (p) 1978 - Analogico - (op.

6)

Philips - 835 289/291 - (3 LP's) -

durata 42' 44" | 41' 39" | 44' 14"

- (p) 1965 - Analogico - (op. 9)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6

CONCERTOS, OP. 6

In 1716-17 the Amsterdam

publisher Estienne Roger

brought out three

collections of

instrumental music by

Vivaldi, using the imprint

of his daughter and

heirdesignate Jeanne.

These comprised a set of

six sonatas, Op. 5, and

two sets of concertos, one

(Op. 6) containing six and

the other (Op. 7) 12

works. The initiative for

their publication almost

certainly came from Roger,

for had the project

originated with the

composer, he would surely

have provided dedications

for them, as he had done

in Op. 3 and Op. 4 and was

to do again in Op. 8 and

Op. 9. The fact is that in

the wake of the enormous,

continent-wide success of

Vivaldi’s first two

collections of concertos

there was an insatiable

demand for his music which

Roger would naturally be

eager to satisfy.

Although Vivaldi’s

reputation had been

founded on instrumental

music, his field of

activity had suddenly

widened in the mid-1710’s

to embrace both sacred

vocal music and opera. The

abrupt departure from the

Pietà (the

Venetian

orphanage-cum-conservatoire

where he held the

positions of violin master

and orchestral director)

of its choirmaster

Francesco Casparini meant

that from 1713 until

perhaps as late as

1717-18, when Vivaldi took

up residence in Mantua, he

was required to compose

music for the chapel (his

great oratorio “Juditha

triumphans” dates from

1716). Concurrently, he

was kept busy at the

Sant’Angelo opera house as

impresario and resident

composer-arranger. During

these years, therefore,

instrumental composition

must have been pushed

somewhat into the

background.

Although the 6

concerti a cinque

stromenti, Op. 6,

pose no problems of

authenticity, unlike some

of their Op. 7

counterparts, the

uncommonly numerous errors

in Roger’s published parts

are not all easy to

correct. It

is interesting that the

figuring of the organo

part (organo is a generic

term for keyboard continuo

instruments, embracing the

harpsichord as well as the

organ) faithfully

expresses the intervals

between the upper string

parts and the bass - even

when a bass note is

clearly wrong; this

suggests that Vivaldi

himself was not

responsible for the

figuring and makes one

wonder whether Roger

acquired the manuscript of

the concertos at second

hand.

Op. 6 is the first

collection to present the

Vivaldi concerto

consistently in its

“classic” form, the

earlier published

collections, Op. 3 and Op.

4, being rather

heterogeneous in style and

often betraying the

influence of Corelli,

Torelli, and Albinoni. All

the Op. 6 works adopt the

three-movement

(fast-slow-fast) cycle; a

single violin suffices as

the solo instrument, and ritornello

form is employed in all

the outer movements except

the finale of No. 3, a

binary movement. Some

variety is offered by the

slow movements, three of

which (in Nos. 1, 2, and

6) are scored for solo

violin and continuo alone

in the manner of a violin

sonata, while the

remainder feature chordal

patterns on the orchestral

strings connected by short

passages of solo writing.

Each work contains points

of special interest. The

opening movement of Concerto

Mo.

1 in G

minor is noteworthy

for its fierce upbeat

patterns, variously

consisting of a single

semiquaver, a run of three

semiquavers, or a grand

sweep of several notes,

and the many fragmentary

statements of its ritornello

material.

The framing ritornello,

for continuo alone, of its

siciliana-like second

movement recalls that of

an aria in a solo Cantata.

The key of Concerto No.

2 in E flat is one

especially remarked upon

by Charles de Brosses, a

French traveller who

visited Venice in 1739,

for being popular in Italy

while virtually unused in

France; Vivaldi was

certainly fond of this key

and chose it for 13 of his

extant solo violin

concertos. Transposed to C

major, the first movement

served as the basis of the

second movement in the

third of the ”Op. 13” (”Il

pastor fido”) sonatas,

which, although published

under Vivaldi’s name in

Paris in 1737, are his

music only insofar as

certain movements borrow

material, freely adapted,

from his concertos.

The opening movement of Concerto

No.

3 in G

minor closely

resembles the finale of

the well-known Op. 3 No. 6

both in its turns of

phrase and in the fact

that the orchestral

violins remain united in a

single part. In

the finale even the

principal (i.e. solo)

violin plays in unison

with its fellows.

Concerto No.

4 in D features in

its opening movement note

raddoppiate (rapid

repeated notes); in music

of the period these are

particularly common in the

keys of C and D major (as

here and in the opening

movement of Bach’s Fifth

“Brandenburg” Concerto),

since they are the keys of

the natural trumpet, in

association with whose

repertoire the device

first achieved popularity

in the late seventeenth

century.

The best of the Op. 6 set

is undoubtedly Concerto

No. 5 in E minor,

the outer movements of

which resourcefully employ

chromatic harmony

(particularly so-called

“Neapolitan” harmony

produced by lowering the

second degree of the

scale). The second solo

episode in the opening

movement displays a

characteristically

Vivaldian trick; the

superimposition of

triplets in the solo part

on duplets in the

accompaniment.

The last work, Concerto

No. 6 in D minor is

notable for some bold

harmony verging on the

bizarre. Its finale

features jagged dotted

rhythms - a style

described elsewhere by the

composer as "alla francese"

(in the French manner).

Michael

Talbot

12 CONCERTOS, OP. 9 “LA

CETRA”

Antonio Vivaldi’s Op. 9

appeared in five

part-books in the lists of

the Amsterdam publisher

Michel Charles Le Cene in

1728. The title page

reads; “La CETRA /

Concerti / Consacrati /

Alla / Sacra / Cesarea,

Cattolica Real Maestà

/ Di / Carlo VI /

lmperadore / e Terzo Re

delle Spagne / di

Bohemia di Ungaria Ec.

Ec. Ec. / Da D. Antonio

Vivaldi / Musico di Violino,

Maestro del

Pio Ospitale / Della

Città

di

Venetia et Maestro di

Capella, / di Camera di

S.A.S.

M.Sig.r Principe /

Filippo Langravio

d’Hassia Darmistaht /

Opera Nona.” The

title “La Cetra” means

approximately ”Lyre” and

its meaning, applied to

the concertos, is

picturesque rather than a

precise description, of

course. The opus consists

of 12 concertos for

strings and continuo.

Eleven of the concertos

have a solo violin part

and for two of these the

violin is scordatura,

i.e. tuned otherwise than

normal, while one, in the

manner of the concerto

grosso, employs two solo

violins. For the most part

therefore we are dealing

with violin concertos,

which in their form and

with regard to the

concertante treatment, are

already considerably

richer than the earlier

pieces of Op. 4. The slow

central movements in

particular give the solo

violin ample scope for cantabile

and richly ornamented

playing, and in general

these solo parts offer

difficulties which were to

be equalled only a

generation later in the

works of Giuseppe Tartini.

The first and last

movements of the Concerto

No.

1 in C rely mainly

on effects of sonority and

rhythmic drive. The

introductory tutti

is comparatively broadly

set up, and its

characteristic parts are

cleverly used several

times as linking elements.

The solo violin indulges

in a rich variety of

figures although the

motives of the ritornello

are, on the whole,

preserved. The C minor Largo

is a cantabile,

sarabande-like movement,

devoted entirely to the

solo instrument and

employing only cello and

organ for the

accompaniment. The final Allegro

in 3/8 measure resembles a

gigue, with the solo voice

executing some supple

arabesques between tuttis

which are notable for

their elaborateness and

their habit of oscillating

between forte and

piano dynamics.

The Concerto No. 2 in

A starts off with a

12-bar theme of “Venetian”

character stated in

unison. There is great

variety in the

accompaniment given to the

solo part: high register

strings - violins and

violas - working unisono

alternate with cello

voices. These two styles

of accompaniment, higly

different in effect, are

introduced according to

the register of the solo

voice, violins and violas

backing it during

high-register passages,

cellos in low-register or

“echo” (piano)

passages. In

the Largo, too,

the accompaniment is

unusual. A dark tone is

achieved by omitting the

violins altogether in the

tuttis, while in the solo

passages, cello and organ

provide the accompaniment.

The last movement is

vivacious and dance-like.

Its

flexibility and

transparency originate in

the three-part string

writing of the tuttis. In

the solos the violin’s

accompaniment is each time

only one voice, either the

high strings in unison or

the cello.

In

the Concerto No. 3 in

G

minor the 16-bar ritornello

of the first movement is

divided into two parts.

The first part offers a

tightly worked motive,

full of suspended notes,

the second a predominantly

vocal motive on a simple

chord foundation which all

the violins play together.

A variation of this motive

is now taken up by the

solo violin and prolonged

in passage-work and

decoration. The Largo

belongs entirely to the

solo violin. It

begins with a melancholy

theme, accompanied by the

higher strings in an ostinato

quaver motive - cellos,

double bass, and organ are

silent in this movement -

and the solo voice then

launches into some

athletic excursions. The

third movement is a

virtuoso showpiece, with

large areas consecrated to

some dazzling solo

fireworks. The solo violin

is supported by one cello

only, so that the contrast

between solo and tutti

parts is particularly

striking.

The Concerto No.

4 in E is

exceptionally translucent.

Twothirds of the first

movement are given to the

solo violin, with

accompaniment from the

higher strings. This

assures an eerily floating

effect, a certain

weightlessness that

matches the cantilena

and figurations of the

solo instrument to

perfection. In

the Largo the ostinato-style

ritornello is

executed by violas,

cellos, and double-bass

(without the organ), while

the accompaniment to the

solo part is played by

violas only. In this

movement, too, the solo

violin goes entirely cantabile.

The last movement is

luminous and energetic.

Transparency in the ritornelli

is achieved by much two

and three-part writing,

careful regard for

sonorities, and other

devices; and in one of

them, the relative minor

is strongly established.

The solo violin revels in

many rhythmic and

figurative variations

sometimes capricious,

sometimes cantabile,

but preserves throughout a

light touch.

The Concerto No. 5 in

A minor is the-only

one in this series to

diverge slightly from the

usual straightforward

three-movement scheme. A

five-bar Adagio

introduction is placed

before the first movement,

a storming Presto,

and a solo-dominated Largo

follows immediately after

the Presto. The

final movement is an Allegro

in 4/4 that, from its

character, could equally

well figure as a first

movement. In

this last movement a

perfect equilibrium is

maintained between the

solo and tutti parts, but

in the earlier Presto

the solo instrument is

given decided

pre-eminence. As is usual

in concertos of this

period, the solo

instrument effects the

modulations to

neighbouring tonalities

and these are consolidated

each time by the balancing

ritornello. The

first bars of the Largo

are interesting: they form

a harmonic cadenza which

is ornamented by the solo

violin and this episode

really stands in place of

the usual introductory ritornello.

It is followed by the cantilena

of the solo violin,

accompanied in unison and

piano by the higher

strings.

In the Concerto No. 6

in A the principal

violin is employed with scordatura.

By Vivaldi’s time, scordatura

had become a favourite

means either of extending

the compass of a stringed

instrument or of

permitting it to play

unusual chords, arpeggios,

double, triple, and

quadruple stoppings or

figurations with open

strings according to the

chosen tonality. In this

concerto the tuning

prescribed is a - e' -

a'

- e" for the solo violin,

the other violins being

tuned normally. For the

solo violin this implies a

one-tone transposition for

all tones played on the

two lower strings.

Formally, the first

movement is characterised

by the broadly-framed

introductory ritornello;

but the solo part is here

shaped with greater

caprice and virtuosity

than in the other

concertos. The violin’s

new compass is utilised to

its full in passage-work

and ornamentation, but the

motivic base is well

preserved meanwhile, the

more so as it is properly

represented in the

accompaniment. The ensuing

Largo is similarly

formed. The French

overture rhythm of the

first tutti is

maintained during almost

the entire movement. The

final movement in light,

pastoral vein is in 12/8,

with a suppression of the

virtuoso element in favour

of a long, very intimately

conceived solo episode in

the relative minor.

In the Concerto No.

7 in B flat

the first and last

movements are

conventionally styled. The

first movement passes

through effective

modulations, particularly

in the solo episodes,

while the third movement

is distinguished by its

clever work in the

accompanying motives. Both

movements feature in

common a tight

contrapuntal interweaving

of ostinato

motives. The Largo

is fashioned in an

original way; the

rhythmically uniform, cantabile

line of the solo violin is

accompanied by a regular

quaver movement, shared by

violins and violas.

The Concerto No. 8 in

D minor is opened by

a beautifully textured

motive shared by high and

low strings. The same

concern for sonorities

characterises the

figurations of the solo

violin, which presents us

with triads, thirds, and

rich passage-work, a

concern pursued in the Largo

where the accompaniment to

the solo voice is

particularly fine. This

gracefully devised

movement is, like the

first and last movements,

in D minor. The finale

opens very decidedly, and

solemnly. The ritornello,

brought back five times,

though not always in full,

is kept in three parts and

is thus very transparent.

The figurated solo violin

part plays mostly over a

simple bass accompaniment.

With its two obbligato

violins the Concerto No.

9 in B flat

is a true concerto

grosso.

Here too, the transparency

and flexibility of

three-part writing is

maintained over long

stretches. The trio-like

element is heard at best

in the solo passages,

where the two solo violins

are allowed alternate

access to the motives,

supported by a cello that

forms a sparse bass line.

The first Allegro

is well balanced in the

proportions allotted the

solo and tutti parts. In

the ritornello

the final motive, repeated

in the manner of an echo,

is extremely attractive.

The second movement, Largo

e spiccato, is a

model of its kind. A

rather large ritornello,

given in full at the

beginning of the movement

and brought back in

briefer form to mark the

modulatory points,

supports spiccato

chords that, in

particularly resonant

concert-rooms and played

with a large orchestra,

achieve splendid effect.

The final Allegro

is gigue-like and moves

flexibly through phrases

of well-balanced tension

and relaxation.

In

the sonorous first

movement of the Concerto

No.

70 in G

the semiquaver passages in

the cellos contrast with

the broken triads of the

violins. A four-bar trio

group, kept piano,

provides an attractive

inner contrast within the

broadly framed

introductory ritornello.

Two rather large solo

passages, one on the

tonic, the other on the

dominant, allow arpeggios

to the principal voice

over pedal bass-notes,

while the rest of the

strings share in an octave

motive of quaver value.

The middle movement, Largo

cantabile,

is a sort of serenade. The

simple, well-rounded cantilena

of the solo violin arises

over the continuous

pizzicato accompaniment of

the violins and violas,

lower strings and organ

being omitted. In

the third movement the

most varied thematic

fragments are welded into

a convincing whole. A

dotted opening motive is

followed by a cantabile

insertion. This same event

is repeated in the

dominant. Then comes a

sharp sequence to be

followed again by a cantabile

section which prepares for

the entrance of the solo

violin. The solo part

takes up motives of the ritornello

and develops them further,

and through them finds

opportunity for virtuoso

stunts and rich

modulation.

The first and last

movement of the Concerto

No. 11

in C minor are

worked in tight four-part

writing. In

both, all devices -

tonality, lightly-sketched

fugal treatment, scalwork

- are traceable

manifestations of the

Baroque “science of

composition” based on

treatment of the "affection."

The Adagio starts

with a ritornello

of quaver chords, in which

two chords played forte

are followed by two piano.

In the middle of the

movement the solo voice is

allowed expressive play. In

the third movement the

characteristic turn of the

Neapolitan sixth chord,

can be recognised in the

introductory and final ritornelli.

The four lengthy solo

passages are dramatically

related: each develops its

predecessor in point of

intensity of argument and

expansion of the material.

The Concerto No. 12

in B minor again

demands (like No. 6) scordatura

for the solo violin. This

time the tuning is b - d' -

a'

- d", in keeping with the

B minor tonality. In the

two quick movements the

solo part is given rich

virtuoso material. Apart

from the customary figures

and accompaniment there

is, in the first movement,

a rather long solo passage

with unusual further

parts: second violins and

violas execute the quaver

accompaniment and the

first violins play the

principal melody while the

solo violin adds virtuoso

arpeggios. The Largo

subsists entirely on

motives played in unison.

The whole orchestra takes

part in the tutti and for

the accompaniment of the

solo violin only the high

strings are used. The solo

violin offers

double-stoppings and an

ornamented cantilena.

The last movement is

lucidly transparent.

Three-part writing,

chordal quaver

accompaniment by the

higher strings in the solo

passages, and rhythmically

taut motives are

especially favoured. Here,

as in the first movement,

certain unusual effects of

violin technique appear,

of the kind Tartini was to

exploit later.

Franz

Giegling

|

|