|

|

5 LP's

- 6768 009 - (c) 1978

|

|

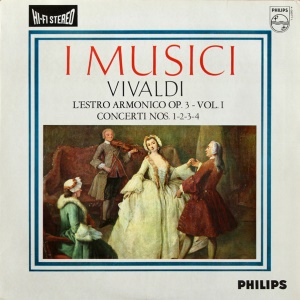

| 1 LP -

835 162 - (p) 1963 |

|

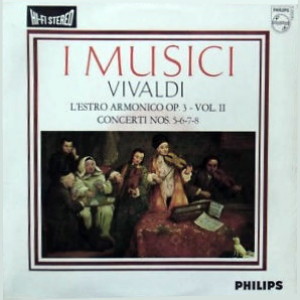

| 1 LP -

835 162 - (p) 1963 |

|

| 1 LP -

835 163 - (p) 1963 |

|

| 1 LP -

835 209 - (p) 1963 |

|

| 1 LP -

835 210 - (p) 1963 |

|

EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

35' 32" |

|

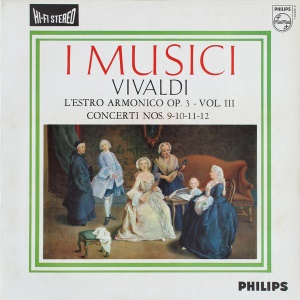

12 Concerti op. 3

für eine, zwei oder vier Violinen,

Streciher und Continuo "L'Estro

armonico"

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 1 D-dur mit vier

oggligaten Violinen, RV/R. 549 (P.

146) |

8' 49"

|

|

|

-

Concerto Nr. 2 g-moll mit zwei

obligaten Violinen und obligatem

Violoncello, RV/R. 578 (P. 326)

|

11' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 3 G-dur mit obligaer

Violine, RV/R. 310 (P. 96) |

7' 09" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 4 e-moll mit vier

obligaten Violinen, RV/R. 550 (P.

97) |

8' 20" |

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

40' 24" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 5 A-dur mit zwei

obligaten Violinen, RV/R. 519 (P.

212) |

8' 11" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 6 a-moll mit obligater

Violine, RV/R. 356 (P. 1) |

8' 40" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 7 F-dur mit vier

obligaten Violinen und obligatem

Violoncello, RV/R. 567 (P. 249) |

11' 42" |

|

|

| - Concerto

Nr. 8 a-moll mit zwei

obligaten Violinen, RV/R.

522 (P. 2) |

11' 51" |

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

41' 18" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 9 h-moll mit obligater

Violine, RV/R. 230 (P. 147) |

8' 22" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 10 h-moll mit vier

obligaten Violinen und obligatem

Violoncello, RV/R. 580 (P. 148) |

10' 28" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Concerto

Nr. 11 d-moll mit zwei

obligaten Violinen und

obligatem Violoncello, RV/R.

565 (P. 250)

|

11' 24"

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 12 E-dur

mit obligater

Violine, RV/R. 265

(P. 240) |

11' 04" |

|

|

| Long Playing

4 |

|

53' 20" |

|

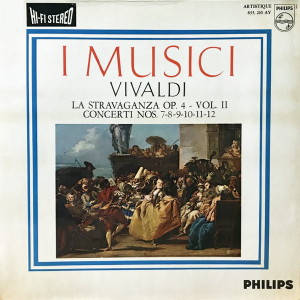

12

Concerti op. 4 für Violine,

Streicher und Contibuo (Orgel) "La

Stravaganza"

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 1 B-dur,

RV/R. 383a (P. 327) |

8' 54" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 2

e-moll, RV/R. 279

(P. 98) |

10' 38" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 3

G-dur, RV/R. 301 (P.

99) |

9' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 4

a-moll, RV/R. 357

(P. 3) |

9' 20" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 5 A-dur,

RV/R. 347 (P. 213) |

10' 20" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 6

g-moll, RV/R. 316a

(P. 328) |

9' 58" |

|

|

| Long Playing

5 |

|

52' 17" |

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 7 C-dur

mit zwei Violinen

und obligatem

Violoncello, RV/R. 185

(P. 4) |

9' 04" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 8 d-moll

(Continuo: Cembalo),

RV/R. 249 (P. 253) |

7' 31" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 9 F-dur,

RV/R. 284 (P. 251) |

8' 17" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 10

c-moll, RV/R. 196

(P. 413) |

8' 50" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 11

D-dur, RV/R. 204 (P.

100) |

7' 15" |

|

|

| -

Concerto Nr. 12

G-dur, RV/R. 298 (P.

100) |

11' 20" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Op.

3 "L'Estro armonico"

|

Op.

4 "La Stravaganza" |

|

Roberto Michelucci, Violine

(Nr. 1-12)

|

Felix Ayo, Violine

(Nr. 1-12)

|

|

Walter Gallozzi, Violine

(Nr. 1,4,7,10)

|

Walter Gallozzi,

Violine (Nr. 7) |

|

| Anna Maria

Cotogni, Violine (Nr.

1,4,7,8,10,11) |

Enzo Altobelli,

obligates Violoncello |

|

| Luciano Vicari,

Violine (Nr. 1,4,7,10) |

I MUSICI |

|

| Italo

Colandrea, Violine (Nr.

2,5) |

Maria Teresa

Garatti, Orgel und Cembalo |

|

| Enzo

Altobelli, Violoncello

(Nr. 2,7,10,11) |

|

|

| I MUSICI |

|

|

| Maria Teresa

Garatti, Cembalo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

La

Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) -

settembre 1962 (op. 3, nr.

1,3,4,6,7,9,10,12)

Schweningen (Olanda) - giugno 1962

(op. 3, nr. 2,5,8,11)

La Chaux-de-Fonds (Svizzera) -

luglio 1963 (op. 4)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 835 162 - (1 LP) - durata 35'

32" - (p) 1963 - Analogico - (op.

3, vol. 1/3)

Philips - 835 163 - (1 LP) -

durata 40' 24" - (p) 1963 -

Analogico - (op. 3, vol. 2/3)

Philips - 835 164 - (1 LP) -

durata 41' 18" - (p) 1963 -

Analogico - (op. 3, vol. 3/3)

Philips - 835 209 - (1 LP) -

durata 53' 20" - (p) 1963 -

Analogico - (op. 4, vol. 1/2

Philips - 835 210 - (1 LP) -

durata 52' 17" - (p) 1963 -

Analogico - (op. 4, vol. 2/2)

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"L'ESTRO

ARMONICO,"

OP. 3

Vivaldi’s

Op. 3 was published about

1712 by Estienne Roger of

Amsterdam, and bears the

title ”L’Estro

armonico” (approximately

translated: "Harmonic

inspiration"). There are

12 concertos in the opus,

which was the first of his

concerto collections to be

published. The individual

concertos can be

classified according to

setting: four are written

for solo violin, four for

two violins, and four for

four violins, all with the

accompaniment of strings

and harpsichord. The

majority have three

movements; sometimes a

slow introduction is added

as in the second concerto,

or the piece is opened by

an animated “Perfidia” as

in the eleventh concerto.

The sequence of the

movements in the fourth

concerto,

slow-quick-slow-quick, is

reminiscent of the church

sonata. For the rest,

Vivaldi prefers the North

Italian concerto type,

primarily established by

Giuseppe Torelli, and

characterised by the

differentiation of

thematic material between

solo and tutti

parts. These concertos are

therefore not constructed

as, for example, those of

Pasquini and Corelli, on

the principle of an

identical content for soli

and tutti, but

develop from varied

thematic material which is

suited to the different

abilities of soloists and

ripienists. Thus the tutti

ritornelli are

usually built on broad,

weighty themes, while the

solo parts have virtuoso

passages and richly

embellished fioriture.

Six of these concertos

were later arranged for

organ or clavier by J.

S. Bach: No. 3 (transposed

to F major), No. 7, No.

8, No.

10 for four claviers and

transposed to A minor, No.

11,

and No. 12, transposed to

C major.

A comparative examination

of these concertos in Op.

3 compels one to marvel at

the richness and diversity

of Vivaldi’s invention,

his sense of form and

sonority, and at his

command of instrumental

writing. They reveal

Vivaldi the great

craftsman, and also the

tireless experimenter. In

this respect the title

”L’Estro armonico” for Op.

3 is entirely appropriate.

The first concerto in D is

for four violins obbligati

and one solo cello. The

opening movement already

makes it clear that

Vivaldi is not slavishly

copying an adopted form,

but freely and ingeniously

modifying the formal

principle. First and

second solo violins begin

with an imitative theme,

which does not appear

again in this form; its

quaver figure is later

taken over for the most

part by the tutti,

while the solo violins and

cello retain the

semiquaver figure. In

the middle movement a

descending theme in octave

unison forms the thrice

repeated ritornello,

while the solo

violins play figurations

over an accompaniment from

the violas. The work ends

with a lively, extended

movement in 9/8 time. Here

for once soli and

tutti have

identical thematic

material, which in the

long solo sections

is freely extended in

figurations and passage

work.

The second concerto in C

minor for two violins and

cello obbligati is

prefaced by a slow

introduction, which by its

mood and solemnity,

suggests that the piece

was written for the

church. The tutti

theme of the subsequent Allegro

is based on a semiquaver

run, spanning the octave,

which becomes increasingly

agitated. The solo violin

passages also have running

semiquaver figures, which

are contrasted with the tutti

motive. In the Larghetto,

chords in dotted rhythm,

now loud, now soft, form

the ritornello. In

between times, a cantilena,

also in dotted rhythm, is

interposed in the tutti,

and echoed by the solo

instruments. The final Allegro

is in 12/8 time, and in

the manner of a gigue. A

brief chromatically

ascending motive offers

some surprising harmony.

In the third work, a solo

concerto in G, the solo

violin takes on special

prominence in the second

and third movement. After

a bar by bar exchange

between solo and

tutti, the cantilena

becomes more and more

extended in the middle

movement. In the last

movement the lengthy solo

passages are accompanied

by the higher strings - a

device also used by Mozart

- or by tutti

chords. Along with the

requisite modulation to B

minor, the first movement

is a particularly fine

example of the standard

concerto form.

Unlike the others, the

fourth concerto in E minor

for four violins has four

movements. A dotted motive

melodically differentiated

between soli and tutti,

gives unity to the first Andante.

In the following Allegro,

the solo violins usually

play singly or at most in

pairs. The mellow

atmosphere of the opening

movement is here relieved

by an opulent virtuosity.

A brief Adagio -

only a few bars long -

provides a breathing space

before the brisk attack of

the closing Allegro,

with its continuous

animated impetus. The

simplest harmonic

relationships, constant

interplay of soli

and tutti and the

transparent quality of the

writing lend the movement

the elegance and polish

which we always admire

afresh in Vivaldi.

In

the fifth concerto in A

for two violins obbligati,

the bold unison opening,

extending over nine bars,

bears the true Venetian

stamp: Benedetto Marcello

once said that a unison

played majestically and

with fire by massed

strings

is always

effective. This unison

beginning appears as a ritornello

three times in the course

of the first movement. In

between come finely

chiselled solo

passages for the violins,

sometimes without bass

support, sometimes

accompanied by delicate

quaver chords. The middle

movement is entirely

reserved for the first solo

violin, which soars above

soft quaver chords from

the upper strings,

initially in a flowing cantabile,

later developing into

light fioriture.

The closing Allegro

alternates frequently

between solo and tutti

passages. Triad figures

predominate in the tutti

motive, while the solo

violins make much use of

trills and scales.

Through republications,

the sixth concerto in A

minor for violin was one

of the earliest of

Vivaldi’s concertos to

become well known. This

early popularity is as

much due to the striking

first and last movements,

as to the beautifully

shaped Largo.

The seventh concerto in F

for four violins and cello

obbligati

opens with a broad Andante

in which the solo instruments

are given ample

opportunity for display,

singly, or two or three

together, in the manner of

a trio sonata or sonata a

quattro. A lively,

decidedly virtuoso Allegro

follows, framed by two Adagio

sections. This

triptych form is in

keeping with the

North-Italian concerto

form as divised by

Giuseppe Torelli. ln the

final Allegro, in

3/4 time, solo and

tutti passages are

for the most part allotted

identical motives, a rare

practice with Vivaldi.

The eighth concerto in A

minor for two violins is

at once notable for

spaciousness of treatment.

As in the classical

concerto, the principal

motives are introduced in

the first tutti.

The two solo

violins shape and develop

this material with great

ingenuity. In the middle

movement, the unison ritornello

of the opening

returns as a basso

ostinato during the

solo section,adevice later

used by J.

S. Bach in the middle

movement of his E major

violin concerto. The last

movement shows the same

breadth of treatment as

the first. The solo

passages are extended by

rich and sequenced

figurations, and usually

set contrapuntally against

interesting

counter-voices.

The ninth concerto in D

for violin obbligato

is more of a virtuoso

work. The

characteristically

clear-cut, somewhat robust

opening theme of the first

movement develops into a

continuous animated flow,

both in the solo

and in the tutti,

until a pedal point

several bars long calls a

halt, and

leads into the closing ritornello.

The Larghetto is

also in D, and allows the

solo violin to

display itself above a

quaver accompaniment from

the upper strings. The

closing Allegro is

even more a virtuoso

piece. The violins begin

portentously with a wind

passage, a fanfare as it

were, heralding the entry

of the tutti in

rapid semiquavers. The solo

part abounds in the most

varied figurations and

passes into

demisemiquavers.

The tenth concerto in B

minor for four violins and

cello obbligati

has become known and loved

in J.

S. Bach's

transcription for four

claviers. The less

well-known original has a

more gentle, gracious

atmosphere. The dense

texture, as much as seven

voices in counterpoint,

calls to mind the

orchestral sonatas and

concertos of Vivaldi’s

contemporary Albinoni. In

the first and last

movement the solo violins

are variously combined

with the solo

cello. Each solo

instrument is entrusted

with particular tasks.

There is a wealth of

contrast between solo

and tutti

sections, as the dense

polyphony of the tutti

is often relieved by solo

passages above pure

continuo. In

the Larghetto,

Vivaldi achieves very

notable effects in the

violin arpeggios, since he

calls for four different

methods of articulation.

The eleventh concerto in D

minor for two violins and

cello obbligati opens with

a so-called ”Perfidia”:

the two solo

violins imitate each other

in triad figures, and the

solo cello answers

them with figurations

above throbbing quavers.

Three bars of adagio

lead to the succeeding fugato,

with the entry of the solo

instruments; this

dissolves into an

interlude passage and,

over a lengthy pedal point

on the dominant, leads to

the conclusion. In

the second movement, a few

tutti bars frame a

somewhat pastoral cantilena

in the solo

violins, above pianissimo

chords in the violins

and violas. In

the finale, the solo

violins maintain a

vigorous pace, outbidding

each other in motives, and

contrasted by a

chromatically descending

motive in the solo

cello. The movement has a

number of solo

passages, mostly allotted

to the first violin.

Like No. 6, the twelfth

concerto in E for violin obbligato

became known comparatively

early through

republications. The accent

here is on sonorities. In

the first and last

movements triad figures

predominate, both in the

concisely worked tutti

ritornelli,

and in the virtuoso solo

passages. The

delicate, transparent

accompaniment gives the

slow movement a

particularly light and

unencumbered effect.

"LA

STRAVAGANZA," OP.

4

The 12 concertos of Op. 4

bear the collective title

“La Stravaganza" (meaning

approximately "Flight

of fancy") and were

published in the usual

form of partbooks by

Estienne Roger of

Amsterdam about 1715. The

instrumentation is the

same for all 12 concertos:

one solo violin,

two ripieno

violins, viola, and basso

continuo. Except for No.

7, which has four

movements, the concertos

are all in three

movements, and the

sequence for each, Allegro

- Largo - Allegro,

is the usual one in the

Italian concerto. The

occasional use of a

four-movement sequence is

a reminder of the descent

of this form from the sonata

da chiesa.

In

this connexion, it should

be remembered that the

concerto form had its

origin in the sumptuous

musical usage of the late

seventeenth-century Church

of Upper Italy. The Mass

was not only musical, with

solo inserts and choral

sections for one or more

choirs, but instrumental

pieces were also

interpolated between the

separate parts of the

Mass: violin concertos,

concertos for oboes and -

by an old tradition - for

trumpets, strings, and

organ. From the Church,

these newly-devised forms

made their way into the

courts of princes, and

into the seminaries,

colleges, and academies,

which, nurtured by a

growing demand for music,

brought into fashion the

public concert.

Vivaldi was well placed to

bring the instrumental

forms to their first

maturity. He freed the

originally schematic and

equally spaced exchange of

ritornello and solo

of all rigidity and

convention and made from

it a formal structure in

which solo

and tutti develop

organically. The 12

concertos of Op. 4 form a

collection which uses all

the resources open to the

composer of violin

concertos at this time. Of

particular significance is

the shape given to the solo

violin part. Vivaldi

sometimes allows it to

begin with the principal

subject, and freely

develop, sometimes he

invents in addition an

independent contrasting

theme, or else allows the

violin to indulge wholly

in figuration. The forms

of the accompaniment are

also very varied. The most

simple is the

accompaniment by basso

continuo, either by cello

alone or cello and organ

(harpsichord may be

substituted).

As frequently happens in

Vivaldi's

music, accompaniment is

also provided by the upper

strings, or by the two

violins alone or together

with the viola, in either

case without bass. This

form of accompaniment

lasted right up to the

time of Mozart’s

violin concertos. Finally

there is the accompaniment

by the full ensemble,

either in simple chords or

in counter-themes.

As with Op. 3 (“L’Estro

armonico”), several

movements from Op. 4 were

later given fresh

treatment by J.

S. Bach. He transposed the

first movement of the

first concerto of Op. 4 to

G

major, and arranged it for

a keyboard instrument. In

addition he made keyboard

transcriptions of the

first two movements of the

G

minor concerto No. 6,

richly embellishing the Largo.

The first concerto in B

flat opens with a

close-textured tutti

ritornello in the

manner of Albinoni. The

four solo

entries with intervening ritornelli,

place the first violin

well in the forefront, but

bring in another violin

and a cello to second and

accompany (a formal link

with the trio sonata). The

slow middle movement, Largo,

belongs entirely to the solo

violin, the strings under

the direction “sempre

piano” confining

themselves to a simple

quaver accompaniment. The

last movement stresses tutti

passages. A richly

modulating section of over

100 bars takes up the

greater part while the

violin solo,

which is only half as

long, is based wholly on

figurations. A 10 bar ritornello

rounds the work off.

The second concerto is in

E minor, and also has

three movements. With the

exception of sizable ritornelli

at the start of the first

and last movements, it

offers most of its chances

to the solo

violin - from the simple

rhythmic variation of a

motive, to the virtuoso

embroidery of the

principal theme. The ways

in which the solo

instrument is accompanied

are interesting and

varied: simple quaver

figures in the upper

strings basso continuo

alone, the tutti

with simple piano chords,

or with related quaver

figures. This kind of

treatment really

summarises the stylistic

habits of the age, at

least in the matter of

accompaniment.

The first movement of the

third concerto in G is

motivistically almost

wholly built on common

chord figures. The solo

violin also launches into

the main subject in

figurations derived from

the common chord.

The second movement, a Largo

in B minor, 12/8 time,

offers strong contrast in

its warm, intimate

content, which is explored

mainly by the violin,

accompanied by the upper

strings. The work ends in

virtuoso style with a

gigue-like Allegro

assai.

The fourth concerto in A

minor, a serious and

weighty piece, has a

recurrent unison ritornello

which gives the first

movement a majestic

solemnity.

In the following Grave,

the solo

violin sings over dotted

rhythms in the upper

strings, and the closing Allegro

gives the violin ample

opportunity for display

with four sizable solo

sections. The final ritornello's

unisono effects hark

back to the first

movement.

In

the fifth concerto in A

the solo violin is

assigned extended

passages, sometimes of

considerable technical

difficulty. With the

exception of the first,

the tutti ritornelli

are kept shorter. In

the slow middle movement,

which has no ritornello,

the solo part is

particularly rich and

free.

The sixth concerto in G

minor is a work of more

conventional cut. Ritornelli

and solo

sections alternate fairly

regularly. In

the first movement, the solo

violin takes up the

principal motive of the ritornello,

and extends it in

figurations. The last two

solo

entries are interesting in

that two more solo

violins and viola, or the

cello, play

counter-motives to the

principal violin. The

middle movement, a Largo

in D minor, belongs mainly

to the solo

violin, whose part is

simple and song-like. In

the last movement, the solo

instrument again has a

very rich entry, and its

part is notable for some

rapid virtuoso triplet

figures.

The

seventh concerto in C is

the only four-movement

piece in the opus. The

sequence Largo -

Allegro

- Largo - Allegro,

and the construction of

the solo sections,

scored almost entirely

as trios between two

violins and cello,

underline the concerto’s

descent from the sonata

da chiesa. The

initial Largo

begins in ceremonious

style, with the broken

chord of C major. The

freely fugal Allegro

also attracts the lower

strings into the

semiquaver motion. In

the second Largo,

two violins share the cantilena

in turn, while the

remaining strings carry

the richly modulating

quaver accompaniment.

The work closes with a

sparkling Allegro

in 3/8 time, gigue-like

in manner, as is

frequently the case, and

oscillating rapidly

between soli

and tutti.

The eighth concerto in D

minor which has a

harpsichord instead of

an organ as continuo is

opened by the solo

violin accompanied by

cello. It executes an

oddly jagged motive,

which predominates also

in later solo

entries, and somewhat

influences the tutti

motive. In the second

movement, which follows

the first without pause,

the harpsichord is

allowed effective solo

arpeggios. The

work ends with a

spirited, abundantly

modulating Allegro,

with extensive solo

passages.

The ninth concerto in F

is another work of

rather ecclesiastical

solemnity. Interesting

in the first movement is

the way the semiquaver

impulse passes

continually between the

upper and lower voices,

The solo

sections are nearly all

a tre that is,

for two violins and

cello. In the middle

movement, the dotted

rhythms of the tutti

predominate, with

soloistic inserts for

the violin. The tutti

sections of the last

movement are again very

closely textured, and

the solo

violin, accompanied by

the cello provides apt

contrast.

In

the tenth concerto in C

minor, the tutti

ritornelli

of the first and last

movements are composed

almost entirely in three

voices, the two violins

playing mostly in

unison. The dotted

rhythm at the start of

the first movement is

French in flavour, with

the principal motive

taken up by the solo

violin, and extended

into agile figurations.

The Adagio which

follows without pause,

gives the soloist a

simple, but very

sensitive cantilena,

framed by two tutti

sections. The principal

feature of the closing Allegro

is the rapid exchange

between solo

and tutti,

enhanced by brief,

interpolated unison

passages, and by the

spirited solo

violin part.

The eleventh concerto in

D begins with a

“Perfidia” between two solo

violins without bass.

The tutti

ritornello, a

fine, ringing chord

motive, remains in

unison in the first

movement. The second

movement, a Largo

in B minor is shared by

the solo

violin and solo

cello, the latter

playing almost

uninterruptedly in

semiquavers. The closing

movement is blithe and

sparkling. The tutti

sections take care of

the themes and

modulations, while the solo

violin accompanied by

one cello provides the

contrast in tone and

playing technique.

The twelfth and last

concerto is in G. In

the first movement soli

and tutti

are interwoven, both

contributing in equal

measure to the formal

development. In

the Largo, the solo

violin, accompanied most

of the time by the

entire strings, has a

richly embellished part

framed by two tutti

ritornelli. The

last movement belongs

mainly to the solo

violin, with brief

interruptions from the tutti.

The violin part is amply

provided with

figurations, and also

with cantilene.

In

this closing movement,

Vivaldi once again draws

on all the devices of

instrumental

compositions known to

his time.

Franz

Giegling

|

|