|

|

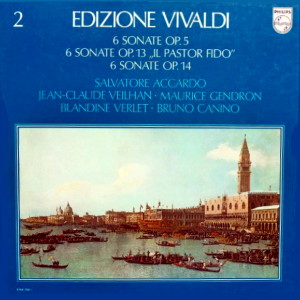

3 LP's

- 6768 750 - (c) 1978

|

|

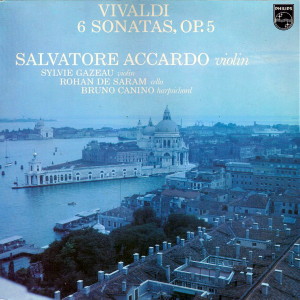

| 1 LP -

9500 396 - (p) 1977 |

|

| 1 LP -

6504 009 - (p) 1970 |

|

| 1 LP -

802 818 - (p) 1967 |

|

| EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

56' 40" |

|

| 6 Sonaten op. 5 |

|

|

|

-

Nr. 1 F-dur, RV 18

- für Violine und Continuo

|

9'

49"

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 2 A-dur, RV 30 - für Violine und Continuo |

7' 47" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 3 B-dur, RV 33 - für Violine und Continuo |

9' 46" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 4 h-moll, RV 35 - für Violine und Continuo |

10' 03" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 5 B-dur, RV 76 - für zwei Violinen und

Continuo |

9' 49" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 6 g-moll, RV 72 - für zwei Violinen und

Continuo |

9' 26" |

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

52' 00" |

|

| 6 Sonaten für

Blockflöte, mit Cembalo und

Violoncello op. 13 "Il Pastor

Fido" |

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 4 C-dur, RV

59 |

8' 15" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 6 g-moll, RV

58 |

7' 11" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 5 C-dur, RV 55 |

10' 30" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 2 C-dur, RV 56 |

7' 45" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 3 G-dur, RV 57 |

8' 45" |

|

|

| - Nr. 1 C-dur,

RV 54 |

9' 34" |

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

57' 12" |

|

| 6

Sonaten für Violoncello

und Continuo op. 14 |

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 1 B-dur, RV 47 |

6' 50" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 2 F-dur, RV 41 |

10' 55" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 3

a-moll, RV 43 |

10' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 4 B-dur,

RV 45 |

10' 12" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 5

e-moll, RV 40 |

9' 25" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 6

B-dur, RV 46 |

9' 40" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sonaten op. 5 |

Sonaten op. 13

"Il Pastor Fido"

|

Sonaten op. 14 |

|

| Salvatore Accardo,

Violine |

Jean-Claude Veilhan, Blockflöte |

Maurice Gendron, Violoncello |

|

Sykvie Gazeau,

Violine (5 & 6)

|

Blandine Verlet, Cembalo

(Ruckers) |

Marijke Smit Sibinga, Cembalo |

|

| Bruno

Canino, Cembalo |

Jean Lamy, Violoncello |

Hans Lang, Violoncello

(Continuo)

|

|

| Rohan

de Saram, Violoncello |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Amsterdam

(Olanda) - aprile 1977 (op. 5)

Parigi (Francia) - giugno 1970

(op. 13)

Het Wapen Van Eindhoven (Olanda) -

gennaio 1967 (op. 14) |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 9500 396 - (1 LP) - durata 54'

40" - (p) 1977 - Analogico - (op.

5)

Philips - 6504 009 - (1 LP) -

durata 52' 00" - (p) 1970 -

Analogico - (op. 13)

Philips - 802 818 - (1 LP) -

durata 57' 12" - (p) 1967 -

Analogico - (op. 14) |

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SIX

SONATAS, OP. 5

In

1716-17 the Amsterdam

publisher Estienne Roger

brought out three

collections of

instrumental music by

Vivaldi, using the imprint

of his daughter and

heir-designate Jeanne.

These comprised a set of

six sonatas, Op. 5, and

two sets of concertos, one

(Op. 6) containing six and

the other (Op. 7) 12

works. The initiative for

their publication almost

certainly came from Roger,

for had the project

originated with the

composer, he would surely

have provided dedications

for them, as he had done

in Op. 3 and Op. 4 and was

to do again in Op. 8 and

Op. 9. The fact is that in

the wake of the enormous,

continent-wide success of

Vivaldi’s first two

collections of concertos

there was an insatiable

demand for his music which

Roger would naturally be

eager to satisfy.

Although Vivaldi’s

reputation had been

founded on instrumental

music, his field of

activity had suddenly

widened in the mid-1710's

to embrace both sacred

vocal music and opera. The

abrupt departure from the

Pietà (the

Venetian

orphanage-cum-conservatoire

where he held the

positions of violin master

and orchestral director)

of its choirmaster

Francesco Casparini meant

that from 1713 until

perhaps as late as

1717-18, when Vivaldi took

up residence in Mantua, he

was required to compose

music for the chapel (his

great oratorio "Juditha

triumphans"

dates from 1716).

Concurrently, he was kept

busy at the Sant’Angelo

opera house as impresario

and resident

composer-arranger. During

these years, therefore,

instrumental composition

must have been pushed

somewhat into the

background.

Op. 5 contains four

sonatas for violin and basso

(the catch-all term for

cello, keyboard continuo,

or both combined) followed

by two for a pair of

violins with basso

continuo (here

clearly keyboard continuo,

optionally reinforced by

cello). Mixed instrumental

specifications of this

kind are common in

seventeenth-century

collections, rarer in the

more commercially minded

eighteenth century. In

the contemporary

collection most comparable

in this respect with

Vivaldi’s Op. 5, a group

of eight “solo” sonatas

and six trio sonatas

brought out in Paris by

the Italian émigré Michele

Mascitti as his Op. 4

(1711), the second violin

part in the trios is,

significantly, ad libitum.

The proportion of solo to

trio sonatas in both

collections illustrates

the change in the relative

popularity of the two

settings that occurred

soon after 1700.

All six works in Vivaldi’s

Op. 5 are styled as

chamber sonatas; that is,

they comprise two or three

dance movements introduced

by a Preludio.

With one exception the

dances belong to the five

favoured types: Allemanda

(in moderate to quick

quadruple time), Corrente

(in quick triple time), Sarabanda

(in slightly quicker

triple time), Giga

(in quick compound time -

here, rather unusually,

9/8), and Gavotta

(in very quick duple

time). Slower tempos are

found in the preludes,

which have all but shed

their ancestral connexion

with the opening movement

of the church sonata and

possess a truly dance-like

lilt. The Air-Menuet (was

this title Vivaldi’s?)

closing the last sonata

attests to the huge vogue

for the minuet in the

early eighteenth century.

Vivaldi’s close

contemporary Francesco

Antonio Bonporti had one

hundred of them published

in Venice c. 1710, while

Telemann’s quaintly worded

“Sept fois sept et un

menuet” came out in

Hamburg in 1728. All the

movements in Op. 5 are

cast in binary form,

repeats being prescribed

for both sections. The

greater length of the

second section allows for

modulatory digressions and

sometimes a reprise of the

opening idea.

It is interesting to

compare the solo sonatas

in Op. 5 with their

predecessors of Op. 2

(1709), especially as

Roger designated Op. 5 the

“second part” (parte

seconda) of Op. 2 and

accordingly numbered the

works from 13 to 18.

Although the bass in the

earlier set is named for

harpsichord, its

liveliness and high level

of thematic interaction

with the violin brings the

works very close to the

idiom of the sonatas for

violin and cello (without

continuo) which flourished

in Italy

around the turn of the

century. In Op. 5 the bass

is generally less

ambitious, but one finds

traces of its earlier

manner in the Gavotta

of the second sonata and

the Allemanda of

the fourth. The shape of

things to come is revealed

in the Gavotta

of the third sonata,

however, here the bass

provides a mere strut for

the violin, often

following it in parallel

motion as if to emphasise

its dependence. The style

of the new sonatas is

airier, less intense.

Playfulness is suggested

by the sometimes almost

inane repetition for bars

on end of simple figures.

The trios make an even

greater contrast with

their predecessors of Op.

1 (1705). The former

parity between the violins

is only occasionally

observed (most noticeably,

perhaps, in the Allemanda

of the last sonata); more

typical are passages where

the first violin holds

sway. The second violin

could even be omitted, a

la Mascitti, from the Preludio

of the same sonata without

serious damage. Vivaldi

does not disguise a strong

whiff of the concerto

style. In

several places one could

well imagine one is

hearing one of his chamber

concertos, several of

which are scored for a

trio combination. Looking

at the matter positively,

we might even say that in

these delightful sonatas

Vivaldi is, for the first

time in the sonata genre,

well and truly himself.

Michael

Talbot

SIX SONATAS, OP. 13 "IL

PASTOR FIDO"

We know very little about

the six sonatas for

bagpipe, lyre, flute,

oboe, or violin, and basso

continuo, which under the

title "Il

Pastor Fido" constitute

the Op. 13 of Antonio

Vivaldi. A copy of the

score is preserved in the

Arles Library and another

is to be found in the

Bavarian State Library in

Munich. A third is

reported to be in the

Arsenal Library in Paris.

This version, without

title or signature, is

integrated in a collection

of various pieces for

bagpipe.

The instrumentation of

these works and the fact

that "Il

Pastor Fido" was

published not in Italy but

in France (by Widow Boivin

in 1737) leads one to

think that they could be

arrangements of Vivaldi

compositions by a French

musician. In this

connexion there comes to

mind Chédeville

the Younger,

who showed particular

interest in the works of

Vivaldi.

In

1739 Chédeville

applied for a royal

licence "to adapt.

transpose, and arrange in

a simple manner suitable

for execution by bagpipe,

lyre, or flute" a

number of Italian works by

Vivaldi, including "The

Four Seasons". Finally

he indicated in his

dedication to the Marquis

de Collande

that he wished to adapt

the pieces to the "rustic

tone or the bagpipe" (M.

Pincherle). The bagpipe at

that time in France was

very much in fashion, but

in Italy

it was rarely plaved.

Finally, several movements

of "Il

Pastor Fido"

are taken from different

works by Vivaldi. For

example, the Allegro

assai of the second

sonata is borrowed from an

oboe concerto, the Allegro

ma non presto of the

fourth sonata is from a

violin concerto, and the

sixth sonata's Allegro

ma non presto is

from one of the concertos

of "La Stravaganza"

(similarly transcribed

by J.

S. Bach and arranged for

solo harpsichord). In view

of Vivaldi’s musical

fecundity, it seems odd

that he himself should

have rearranged his

earlier works for other

instruments instead of

writing new compositions.

One thing is sure; the

musical text of these

sonatas is by Vivaldi and

although we cannot prove

that the title "Il Pastor

Fido"

comes from the Venetian

master, it does,

nevertheless, suit this

music extraordinarily

well. Except for the

serious G

minor of the sixth sonata,

we find here a simple,

friendly, rustic form of

expression, which suits

perfectly the bucolic

character of the recorder,

the instrument we have

chosen for this reason

from those proposed in the

preface to the work.

Pains have been taken in

the performance to revive

the rules and usage of the

period (unequal

note values, articulation

pauses, grace notes, etc.)

and, as far as

ornamentation is

concerned, to find a

synthesis of the elegant

style of the French and

the inventiveness of the Italians.

The

Instruments

The recorder, the

harpsichord, and the cello

are all instruments of the

period. They are tuned to

the pitch customary in the

eighteenth century, a

half-tone lower than

normal today. Although the

sound is less brilliant,

it gains in warmth and

timbre.

The recorder, kindly lent

by Mme G.

Thibault-Chambure, of the

Conservatory of the

Instrument Museum, Paris,

is by Christian Schlegel

(Basel, early eighteenth

century). Its unequal

temperament gives it a

very individual sound.

The harpsichord, in which

all the elements are still

authentic, is a large

Ruckers of 1627,

“overhauled” in 1753 and

now the property of C.

Mercier-Ythier. (The

”overhaul” of a

harpsichord was a special

operation common in the

eighteenth century whereby

the sound spectrum of the

keyboard - particularly in

the lower octaves - was

enlarged. This

necessitated enlargement

of the case and changes in

the interior of the

instrument. In

the “overhaul” of this

Ruckers at that period a

lute stop was added to the

upper 8’.)

The maker of the cello was

Jacques

Boquay, who signed this

instrument in 1719. At

that period in France the

cello was beginning to

supplant the bass viol or

viola da gamba, which in

Italy had already

practically disappeared.

The writing of the bass

part and the indication

”violoncello” in the score

of “ll Pastor Fido” leave

no doubt about its use for

the continuo of this work.

This is further confirmed

by the concertante role of

the cello with the

recorder in the Pastorale

of the fourth sonata.

The organ, originally

intended for the Pastorale

of the fourth sonata, is a

positive instrument

constructed by D. Guiraud

and J.

Leguy on the model of

Italian instruments of the

eighteenth century. The

register used here is the

eight-foot bourdon.

J.C. Veilhan

Translation:

David Laird

SIX

SONATAS, OP. 14

About 1740 a publication

appeared bearing the title

“VI Sonates Violoncelle

Solo col Basso da

d'Antonio Vivaldi Musico

di Violino e Musico

de’Concerti del Pio

Ospidale [sic]

della Pietà

di Venezia gravé

par Mlle Michelon, Paris”.

There was no opus number

to the music. Around the

same time several

publishers in Paris

applied for licences to

publish an Op.14 by

Antonio Vivaldi, and in

December 1740 an

announcement appeared in

the “Mercure de France” to

the effect that six

sonatas for cello solo by

Vivaldi had been

published. It is therefore

assumed that the six

sonatas are Vivaldi's Op.

14. Although they were

published in Paris, they

were perhaps written for a

gifted cellist in

Vivaldi’s orchestra at the

Seminario musicale

dell’Ospedale della Pietà.

The primary function of a

viola da gamba or cello

player in the seventeenth

century and the early

eighteenth century was

that of playing the bass

line of all kinds of

music, which was doubled

by the left hand of the

harpsichord player, who

filled in chords over the

bass. In

this way the two players

accompanied solo

instruments, groups of

instruments, and provided

a support for all

orchestral and vocal

music. This unit of

harpsichord and bass

string instrument was the

”basso continuo.”

The cello was first used

to strengthen the bass

part, particularly in the

accompanying of vocal

music, and in orchestral

music, where the powerful

violins drowned the tone

of the gambas. However, in

Italy (where the violin

had been in common use

since the first half of

the seventeenth century,

and for which solo sonatas

were being written in the

second half of the

century) it was found that

the reedy quality of the

gamba provided

insufficient support in

continuo accompaniment,

and that the more powerful

cello balanced better with

the violin. The cello was,

in any case, a member of

the same family of

instruments as the violin,

whereas the viola da gamba

belonged to the older viol

family.

The emergence of the cello

as a solo instrument and

the appearance

of a solo literature for

the instrument was due to

cello virtuosos such as

Franceschini, Gabrielli,

Bononcini, and the famous

Caldara of Venice, who

made composers aware of

the potentials of this new

and powerful instrument.

While the basso continuo

parts of a great deal of

Corelli’s music are

probably for gamba, he is

said to have used the

cello in solo work, for

example in the concertino

section of his concerti

grossi. By Vivaldi’s time

the cello in Italy

had more or less replaced

the gamba in all fields,

and in his concertos he

writes some important solo

passages for it, e.g. in

the Concerto Op. 3 No. 11

the concertino cello takes

just as large a part as

the two concertino violins

in the rapid figurations

and scale passages.

Vivaldi”s interest in the

instrument led him to

write 27 concertos for

solo cello.

These sonatas fall into

the sonata da chiesa

(church sonata) category,

all consisting of four

movements which are

alternately slow and fast.

The sonata da chiesa

and sonata da camera

are usually

distinguishable by the

fact that in the latter

the dance movements are

named as such. Vivaldi,

however, did not make much

distinction between the

two types. Significantly,

the two fast movements of

the sixth sonata have

dance titles - after the Preludio

comes an Allemande,

and after the Largo,

a Corrente. All

other sonatas have fast

movements of similar

character to those of the

sixth sonata, which could

therefore equally well

bear the same titles;

further, the third

movement of the fifth

sonata could be called a Siciliano

rather than simply Largo.

The slow movements in

general exploit the

lyrical sustained sound of

the cello, while the

faster movements

demonstrate its agility

and powers of

articulation. The total

range of the sonatas is

small, the highest note

being A, an octave above

the A string, while the

lowest notes of the

instruments are only

touched upon and are not

tonally exploited in any

way. In

the faster movements

Vivaldi requires the

player to make rapid

string crossings in

executing wide-ranging

leaps -

for example in the second

movements of all the

sonatas and in particular

in that of the third

sonata in A minor.

Although there are several

performing editions of Op.

14 available at present,

the performers on this

recording preferred to use

an eighteenth-century

manuscript of the sonatas.

An edited edition of a

Baroque sonata does not

simply give the editor’s

suggestions about the

performances, but always

includes a realisation of

the bass line for the

keyboard i.e. all the

notes necessary for the

performance of the piece

are present. This has

arisen solely because the

practice of realising the

accompaniment from a bass

line fell into disuse

towards the end of the

eighteenth century. Since

the present revival of

Baroque music, keyboard

players have begun to

practise the art again.

To realise an

eighteenth-century bass

line in the twentieth

century not only requires

a thorough grounding in

keyboard harmony; it also

requires a deep sympathy

with the style of the

Baroque era and a vast

knowledge of the music of

that time in order to make

the turns of phrase and

ornamental figurations

sound authentic. In

the realisation of a

figured bass keyboard

players and editors have

two alternatives. They can

either realise the bass

line in such a way - as in

Luigi Dallapiccola’s

edition of Vivaldi’s

cello sonatas - that a

modern version is made of

an eighteenth-century

piece or, as in this

recording, they can

perform the basso continuo

as authentically as

possible by using a

thorough knowledge of

Baroque musical practice.

|

|