|

|

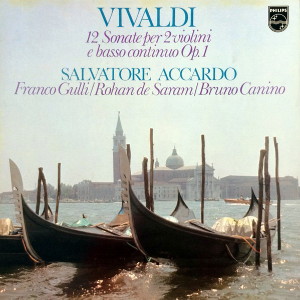

5 LP's

- 6768 007 - (c) 1978

|

|

| 2 LP's -

6747 443 - (p) 1977 |

|

| 3 LP's -

6769 016 - (p) 1978 |

|

| EDIZIONE

VIVALDI - Vol. 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Antonio

Vivaldi (1678-1741) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Long Playing

1 |

|

48' 13" |

|

| 12 Sonaten op. 1

fŁr 2 Violinen und Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 1 g-moll, RV/R. 73 (P.S. 1/1) |

8' 05"

|

|

|

-

Nr. 2 e-moll, RV/R. 67 (P.S. 1/2)

|

8' 39" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 3 C-dur, RV/R. 61 (P.S. 1/3) |

7' 12" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 4 E-dur, RV/R.

66 (P.S. 1/4) |

9' 37" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 5 F-dur, RV/R. 69 (P.S. 1/5) |

6' 41" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 6 D-dur, RV/R. 62 (P.S. 1/6) |

7' 59" |

|

|

Long Playing

2

|

|

48' 09" |

|

| -

Nr. 7 Es-dur, RV/R. 65 (P.S. 1/7) |

9' 44" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 8 d-moll, RV/R. 64 (P.S. 1/8) |

12' 22" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 9 A-dur, RV/R. 75 (P.S. 1/9) |

7' 33" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 10 B-dur, RV/R. 78 (P.S. 1/10) |

7' 46" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 11 h-moll, RV/R.

79 (P.S. 1/11) |

9' 49" |

|

|

| - Nr. 12

d-moll, RV/R. 63 (P.S. 1/12)

"La Follia" |

11' 12" |

|

|

| Long Playing

3 |

|

50' 55" |

|

| 12

Sonaten op. 2 fŁr Violine und

Continuo |

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 1 g-moll, RV/R. 27 (P.S. 2/1) |

12' 34" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 2 A-dur, RV/R. 31 (P.S. 2/2) |

7' 46" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| - Nr. 3

d-moll, RV/R. 14 (P.S. 2/3)

|

15'

22"

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 4 F-dur, RV/R.

20 (P.S. 2/4) |

15' 13" |

|

|

| Long Playing

4 |

|

36' 51" |

|

| -

Nr. 5 h-moll, RV/R.

36 (P.S. 2/5) |

8' 42" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 6 C-dur, RV/R. 1

(P.S. 2/6) |

11' 15" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 7 c-moll, RV/R.

8 (P.S. 2/7) |

8' 57" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 8 G-dur, RV/R.

23 (P.S. 2/8) |

7' 57" |

|

|

| Long Playing

5 |

|

47' 04" |

|

| -

Nr. 9 e-moll, RV/R.

16 (P.S. 2/9) |

14' 17" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 10 f-moll, RV/R.

21 (P.S. 2/10) |

8' 56" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| -

Nr. 11 D-dur, RV/R.

9 (P.S. 2/11) |

10' 39" |

|

|

| -

Nr. 12 a-moll, RV/R.

32 (P.S. 2/12) |

13' 12" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Salvatore Accardo, Violine |

|

Franco Gulli, Violine

(op. 1)

|

|

| Bruno Canino,

Cembalo |

|

| Rohan de Saram,

Violoncello |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Amsterdam

(Olanda) - gennaio 1977 (op. 1)

Amsterdam (Olanda) - novembre 1977

(op. 2)

|

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Producer / Engineer |

|

- |

|

|

Prima Edizione

originale LP |

|

Philips

- 6747 443 - (2 LP's) - durata 47'

13" | 48' 09" - (p) 1977 -

Analogico

Philips - 6769 016 - (3 LP's) -

durata 50' 55" | 36' 51" | 47' 04"

- (p) 1978 - Analogico

|

|

|

Note |

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SONATAS,

OP. 1

In

the late seventeenth and

early eighteenth centuries

the trio sonata enjoyed in

Italy

a status comparable with

that of the string quartet

in Austria during the late

eighteenth century: it was

a genre which ambitious

young composers often

chose for their first

published opus, and like

the string quartet, whose

originator and guiding

spirit was Haydn,

it possessed universally

recognised models in the

four collections which

Arcangelo Corelli

(1653-1713) brought out

between 1681 and 1694.

Corelli consolidated the

division of the sonata

into two types

corresponding to two

functions. The sonata

da chiesa, or church

sonata, was performed,

like much instrumental

music besides, in church

services and consisted of

a cycle of "abstract"

movements, i. e. movements

characterised solely by a

tempo marking. The sonata

da

camera, or chamber

sonata, was music for the

ballrooms of the nobility,

consisting in the main of

dance movements. The

distinction between these

two sub-types, far from

absolute in Corelliís own

music, tended to weaken as

the new century

progressed. As the growth

of music-publishing in

northern Europe attested,

sonatas increasingly

served purely recreational

purposes, so that the

church-chamber antithesis

became one of style rather

than function, hence more

susceptible to blurring.

The earliest known edition

of the 12 "Suonate

da camera a tre," Op.

1, by Antonio Vivaldi is

that of 1705 by the

Venetian printer Giuseppe

Sala, of which only the

first violin part has

survived. It

is possible that this

edition is a reprint of a

lost earlier edition (of

1703?) by Sala; Vivaldiís

clerical status (he was

ordained in March

1703) is acknowledged on

the title-page but,

unaccountably, not his

post of violin master at

the Ospedale della Pietŗ,

which he had held since

September 1703. It

is also puzzling that the

coat-of-arms of the

dedicatee, the Venetian

nobleman Annibale Gambara,

does not make an

appearance, usual in a

Sala first edition, on the

title-page; instead, Sala

has there his own

typographical emblem -

which one associates with

reprints published at his

own expense.

Vivaldiís conventionally

obsequious dedication

contains an attack on

unnamed critics, who, he

says, "are wont in these

times of flaunt their

insolence." It

was almost customary

among composers to

complain in their first

opus of hostile criticism

(the more abjectly to

fling themselves at their

patronís feet!),

but in Vivaldiís case one

catches a hint of the

paranoia which he was to

reveal so blatantly in his

letters to the Marquis

Guido Bentivoglio 30 years

later.

Like most trio sonatas of

the chamber variety, the

present works are for two

violins and a bass part

designated quite

explicitly on the

title-page for violone

(a common term for

continuo cello) or

harpsichord. Ostensibly,

therefore, the cello and

harpsichord are

alternative, not

complementary,

instruments. Whereas in

churches organs were

always available to join

the stringed bass

instrument and amplify the

texture with continuo

harmonies, harpsichords

would not always have been

to hand for the

performance of chamber

sonatas, particularly in

an outdoor setting; this,

and the light, more

homophonic style of dance

movements, may account for

the convention of

providing a single

partbook for the bass. It

should be pointed out,

nevertheless, that some

contemporary sources

possess duplicate bass

parts, suggesting that,

where resources permitted,

performers were glad to

have both a cello and a

harpsichord.

Vivaldiís sonatas follow

the traditional da

camera plan. An

abstract opening movement,

generally modelled on the

slow introductory movement

of the sonata da

chiesa and entitled

"Preludio",

introduces a series of two

or three dance movements

in binary form chosen from

the standard types:

Allemanda, Corrente,

Sarabanda, Giga, and

Gavotta. The Allemanda is

a moderately quick dance

in common time, the

Corrente and Sarabanda

quickish dances (with

slightly differing

rhythmic stylisation) in

triple time, the Giga an

energetic dance (made

slightly grotesque by its

wide leaps) in compound

time, and the Gavotta a

brief, very quick dance in

duple or quadruple time. In

the Sonatas Nos. 1, 3, 6,

8, and 9 Vivaldi,

following Corellian

precedent, inserts short

abstract movements in slow

tempo for the sake of

variety.

The Op.1sonatas are the

only works by Vivaldi so

far known to merit the

description "immature."

This comes out, first, in

his over-addiction to

certain Corellian formulas

(which he may, of course,

have picked up at second

hand) and, second, in the

lack of control in some of

his experimentation. The

opening of the Preludioto

the first sonata,where the

violins leapfrog over one

another, is purest

Corelli, as is the

composite opening movement

of the fourth sonata. The

fifth sonata is greatly

indebted in melody and

harmony to Corelliís

Violin Sonata, op. 5, No.

10

(1700).

The last sonata is a

special case. Sonatas

conceived as a single,

long variation movement,

like the chaconnes in

Corelliís Op. 2 and

Purcellís "Sonatas in Four

Parts," were a recognised,

if rare, form of chamber

sonata. The last sonata of

Corelliís Op. 5, a set of

variations on a 16-bar

theme in chaconne rhythm,

reputedly of Spanish

origin, known as "La

follia"

(Madness), spawned a host

of direct imitations,

including follie

by T. A. Vitali (Op. 4,

1701), Albicastro (Op. 5,

1703), and Reali (Op. 1,

1709). Vivaldiís

imagination, like that of

Liszt or Ravel, was

stimulated by the demands

of virtuosity (inherent in

a variation movement,

where little changes apart

from the figuration),

making this sonata one of

the best in the set and

worthy to stand beside its

model.

An example of Vivaldiís

striving for originality

at its least successful is

the chromatic Preludio of

the third sonata. Some of

the effects strike home:

the ostinato

figuration of the

Capriccio in Sonata No. 1;

the lyrical triplets in

the Allemanda of Sonata

No. 7; the unaccompanied

bass at the start of the

unusually extended Gavotta

in Sonata No. 10; the

opening on first violin

alone (with a "fade-out"!)

of the

Giga in Sonata No. 11, and

the written-out varied

reprises in the following

Gavotta.

Vivaldi left eight extant

sonatas for two violins

and bass besides those

comprising Op. 1, none

exactly comparable. The

two chamber sonatas in Op.

5 (1716) are heavily

influenced by the style of

the "solo"

sonata (in whose company

they appear), while four

works preserved in Turin

manuscripts are really

violin duos with optional

bass. The remaining works

consist of a probably

unauthentic church sonata

in Wiesentheid

and a sonata of mixed

church-chamber type in

Lund. Vivaldiís Op. 1,

therefore, offers unique

evidence of his schooling

in, and contribution to,

one of the main genres of

his youth and early

manhood.

SONATAS, OP. 2

On December 20, 1708 the

Venetians learned that the

young

king Frederik IV of

Denmark and Norway who had

much enjoyed an earlier

visit in 1693 when still

crown prince, intended to

renew his acquaintance

with their city and sample

the delights of its

carnival. This was to be

no official state visit,

as Frederik did not wish

to be distracted by regal

cares; where protocol

demanded a rank, he was to

be known merely as Count

of Oldenburg, one of his

minor titles. Feverish

preparations were made to

receive the visitor; four

nobles agreed to act as

hosts and the savant

Scipione Maffei

was engaged as the Kingís

guide.

Frederik made his entry on

Saturday December 29, and

paid his first visit to

the opera the same

evening. Next morning he

attended Mass in the

chapel of the Pietŗ.

The service included a

Credo and an Agnus Dei

with instrumental

accompaniment as well as

instrumental music.

Francesco Casparini, the

Pietŗís

musical director, was

absent (perhaps he was

supervising rehearsals of

a new opera, "Engelberta,"

of which he was joint

composer); his place at

the rostrum was taken by

an unidentified "maestro."

It

is very possible that this

deputy was none other than

Vivaldi. At any rate he

can hardly have failed to

take part in the

performance and make

himself known to the king.

This chance encounter soon

bore fruit.

Already in late 1708 the

printer Antonio Bortoli

had announced the

impending publication of a

collection of violin

sonatas, Op. 2, by

Vivaldi, in a catalogue

brought out together with

the libretto of Caldaraís

opera "Sofonisba."

Vivaldi seized this golden

opportunity to dedicate

the works to Frederik.

Perhaps he was in time

to present a copy of

his new publication to

Frederik before the king

departed from Venice, on

March 6,1709.

If

Vivaldiís Op. 1 can be

regarded as an almost

mandatory act of homage to

his elder contemporary

Corelli, Op. 2 shows equal

deference to the Roman

master, modelling itself,

like countless

contemporary collections,

on Corelliís Op. 5. More

precisely, the second half

of the Corelli opus, which

contains six chamber

sonatas (the first half

consists of church

sonatas), is the

starting-point. The

Italian sonata da

camera differs from

the keyboard suite in that

the order of the dances is

flexible. In

Vivaldiís Op. 2, for

instance, the giga is the

concluding dance in the

second, third, fifth,

sixth, and tenth sonatas,

but becomes the opening

dance in the first and

eighth sonatas. However,

the gavotta, the

briefest and lightest of

the dances, never occupies

other than last position.

In

some of his sonatas

Vivaldi substitutes on "abstract"

movement for a dance

movement. The second,

third, and twelfth have

short through-composed grave,

or adagio

movements akin in style to

the internal slow movement

of a church sonata; while

the fast movements

variously entitled capriccio

(Nos.9 and12) and fantasia

(No.11) stretch the

technique of the

performers almost in the

spirit of the emerging

solo concerto.The Preludio

a capriccio of the

second sonata opens like

the very first sonata of

Corelliís Op. 5, adagio

sections alternating with

arpeggiated cadenzas over

pedal points, but rather

surprisingly continues as

a through-composed presto.

The bass part in Op. 2

(the title page gives the

harpsichord as the

accompanying instrument)

is more active than in any

of Vivaldiís later

collections of solo

sonatas. Sometimes it has

virtuosic "divisions"

- elaborations in short

note-values of a simple

harmonic foundation, as in

the closing section of the

Preludio

a capriccio

just cited. Often,

however, the bass shares

the principal thematic

material in imitative

fashion with the violin,

so that the two parts have

a high degree of

interdependence. Already

in Op. 5, published as a

sequel to Op. 2, the bass

is less adventurous; in

the 12 "Manchester"

sonatas, a manuscript set

dating from no earlier

than c. 1725, it has

become a mere rhythmic -

scarcely even harmonic - prop.

One has to go back to Op.

2, rooted in an older

tradition, to find good

examples in Vivaldiís

music of contrapuntal

writing in two parts.

Whereas the Op. 1 trio

sonatas have moments of

gaucheness due to

inexperience, the Op. 2

sonatas are fully mature

in regard to compositional

technique. Stylistically

they are less mature as,

on one hand, they are

greatly indebted to

Corelli for their rhythmic

stylisation and the cast

of their themes and, on

the other, they contain

relatively few of the

Vivaldian idiosyncrasies

richly in evidence from

Op. 3 (1711) onwards. A

much-cited example of such

indebtedness is the Allemanda

of the fourth sonata,

which begins with the same

melodic and harmonic

outline as the Gavotta

in Corelli's

tenth sonata (other

variants of the same idea

appear in the F major

works in Vivaldiís Op. 1

and Op. 3). Because of

this close adherence to

Corellian norms the

sonatas of Vivaldi's

Op. 2 bear a strong

likeness to numerous

contemporary works

for the same medium,

including Handelís Op. 1

and Albinonrs Op. 6. No

other works by Vivaldi are

closer to the mainstream

of Italian

instrumental music.

It

remains to single out a

few movements for special

mention. The

recitative-like Adagio

of the second sonata, a

mere eight bars in length,

opens and closes in the

relative minor key (unlike

the church sonata, the

chamber sonata rarely has

a movement in a foreign

key). Invertible

counterpoint is charmingly

displayed in the Preludio

of the fourth sonata. The

Corrente of the

same work was included in

the anthology "Medulla

musicae"

published in London c.

1727, where it was

mistakenly attributed to

Michele Mascitti (c.

1664-1760). (English

musicians must have been

very familiar with

Vivaldiís Op. 2 through

the pirated edition by

Roger of Amsterdam as well

as a native edition by

Walsh.) The broad sweep of

the violin and bass lines

and some unusually

wide-ranging modulation

lend memorability to the Preludio

of the ninth sonata, whose

Capriccio generates

great excitement with its

quick-fire imitations. The

bubbling Capriccio

of the twelfth sonata

shows the closeness of

Vivaldi the composer to

Vivaldi the performer and

points in the direction of

"LíEstro

armonico."

Michael

Talbot

|

|