|

|

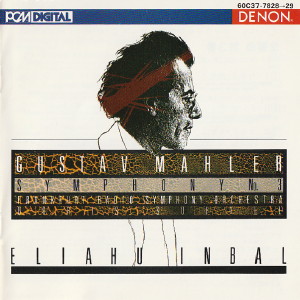

2 CD's

- 60C37-7828-29 - (p) 1986.2

|

|

| GUSTAV MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony No. 3 |

|

|

98' 22" |

|

Compact Disc 1 -

60C37-7828

|

|

|

32' 32"

|

|

| I. Kräftig,

Entschieden |

[IN:DEX

1-8] |

32' 32" |

|

|

Compact Disc 2 -

60C37-7829

|

|

|

65' 50"

|

|

| II.

Tempo di Menuetto. Sehr mäßig |

[IN:DEX

1-6] |

9' 57" |

|

|

| III. Comodo.

Scherzando. Ohne hast |

[IN:DEX

1-7] |

18' 06" |

|

|

| IV.

Sehr langsam. Misterioso. Durchaus

PPP |

[IN:DEX

1-2] |

9' 34" |

|

|

| V.

Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck |

|

4' 03" |

|

|

| VI.

Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden |

[IN:DEX

1-6] |

23' 57" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Doris

Soffel, alto |

|

| Limburger

Domsingknaben / Christoph

Denoix, Conductor |

|

| Women's Chorus of

Frankfurter Kantorei / Wolfgang Schäfer, Conductor |

|

| Frankfurt Radio

Symphony Orchestra |

|

| Eliahu

INBAL |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo e

data di registrazione |

|

Alte Oper,

Frankfurt (Germania) - 18/19

aprile 1985 |

|

|

Registrazione: live /

studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Recording Direction |

|

Yoshiharu

Kawaguchi (DENON / Nippon

Columbia), Clemens Müller

(Hessischer Rndfunk) |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Peter

Willemoës (DENON / Nippon

Columbia), Detlev Kittler

(Hessischer Rundfunk) |

|

|

Mixing Engineer |

|

Norio Okada

(DENON / Nippon Columbia) |

|

|

Technology |

|

Yukio

Takahashi (DENON / Nippon

Columbia) |

|

|

Editing |

|

Hideki

Kukizaki |

|

|

Edition |

|

Universal

Edition AG, Wien |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Denon |

60C37-7628-29 | (2 CD's) | durata

32' 32" - 65' 50" | (p) 1986.2 |

DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Special

Thanks to: Brüel & Kjær.

Co-production with Hessischer

Rundfunk.

|

|

|

|

|

"But I have

written to you that I am

writing on a very large

work. Don`t you understand

that this requires my whole

being and how deeply one is

inflicted with it so often,

so that I seem dead to the

outside world at times."

Gustav Mahler wrote this in

a letter to Anna von

Mildenburg, who lived in

Steinbach am Attersee, the

place where Mahler composed

his third symphony during

the holidays of the Hamburg

theatre between 1893 and

1896. On a meadow sited

between the guest house and

the banks of the sea he had

put up a "Composing-lodge"

with enough room for a

table, chair, sofa and a

piano from Vienna. In the

greatest possible seclusion

he worked there and

disturbing him in his work

meant the threatening of a

death-sentence. The

isolation Mahler required

for his work did not only

cover the outside world.

Bruno Walter, who visited

the composer in 1896 and had

already talked about the

word before he heard in a

performance, explained that

inspiration and the process

of composing did not conform

with Mahler's task of

conducting. In order to he

able to compose, Mahler had

to separate himself from the

outside world and even

persons and matters that

were close to him otherwise.

In his letter to

Madam von Mildenburg he also

says "The creator of such a

work has to bear terrible

labour-pains and before all

this has its correct order

in one’s head, a long period

of seclusion, detraction.

repose and even death for

the outside world has to be

lived through."

Before noon Mahler worked in

his composing-lodge. In the

afternoon he would often

stroll on the meadow or make

long walks into the

mountains and keep himself

busy with musical thoughts

all the time. During a walk

with the composer, Bruno

Walter expressed his

amazement about the

impressive scenery of the

mountains, but Mahler

replied that it would not be

necessary for Walter to look

at it any longer, because he

said to have already

composed every little bit of

the scenery. His statements

become more concrete in the

letters to Anna von

Mildenburg: "My symphony is

going to be something no one

has ever composed before me!

Every part of nature gets

its own voice and tells so

secret things that one could

hardly guess it, even in a

dream. I tell you, sometimes

even I feel so incomfortable

about some passages and it

seems to me that anybody but

me has written this work."

Mahler finds absolute

satisfaction in his

passionate love to nature,

not only because of its

beauty, but also because of

its miraculous and strange

appearance. Alma Mahler

reports on a significant

experience from later years:

"When Mahler was in Mainegg

in the summer, he once came

out of hiss composing-lodge,

bathed in perspiration and

unable to utter a word. When

he finally pulled himself

together and cried: The

heat! The silence! The

panical fear! Horror has

taken possession of him.

This feeling of Pan's

frightful eyes gave him new

horrors and everytime this

happened, he stopped working

and came out of the

seclusion into our house to

find himself in the warmness

of close human beings that

were around him. Only then

was he able to resume his

work." One can hardly follow

this sensitive and close

relationship to nature, but

it is nevertheless the

background for Mahler's

third symphony.

"I find it quite strange

that people talking about

nature only make mention of

flowers, birds and fresh

air. Nobody however seems to

know Pan, the god Dionysos",

he once said to a critic and

went on: "It is all those

nice and horrible

phenomenons that nature is

able to show and I wanted to

put these things in a kind

of evolutionary development

in my work."

Still being in the stage of

composing, Mahler developped

titles and annotations to

every movement. Those title

sketches, as he called them,

are handed down to us in

different versions and they

show the conceptional

development of the symphony.

After having finished the

work with the composition of

the first movement, Mahler,

however, extracted the

seventh movement called “The

heavenly life". This

movement later became the

prime-cell of the fourth

symphony and forms the final

movement.

In their last revision those

title sketches have the

following form:

Section I

l) Pan

awakes. The summer marches

in.(Pan's procession)

Section

II

2) What the

flowers of the meadow tell

me

3) What the

animals in the forest tell

me

4) What man

tells me

5) What the

angels tell me

6) What love

tells me

Slogan:

“Father, see my wounds and

let no I being be lost!"

Later those

title sketches became

victims of Mahler’s red ink,

as well as the programmes of

his first two symphonies. In

a time of an open conflict

between fighters for

absolute music and followers

of programmatic music Mahler

finally had to decide

against any programme, for

the danger of being mistaken

for a programme-musician was

too great. About the first,

however, he wrote: "Summer

marches in and it sings and

sounds. And between that we

have the contrast of a

lifeless, dull nature and a

new world coming to life."

And about the second

movement, which is the basis

for the largely scaled

gradation of the second

section, Mahler says: "This

is the most light-hearted I

have ever written. It is so

light-hearted as only

flowers can be. This music

sounds like flowers bending

in the wind very lightly.

But this cheerfulness

changes into a very serious

atmosphere; like a stormwind

it sweeps over the meadow

and shakes the flowers and

blossoms that whimper on

their stem as if to beg for

redemption into a higher

realm." As he already did in

the second, Mahler refers to

the collection of old German

songs "The boy's magical

horn" by Achim von Arnim and

Clemens von Brentano in his

third symphony, too. The

third movement “What the

animals in the forest tell

me" has its origin in the

vocalization of the poem

"Discharge in summer" that

is about a cuckoo that fell

to death. The trio of the

Scherzando is made up from

the famous “Posthorn

episode", a summer-idyll

that is painted in beautiful

Cantilenes and mild sounds

of the horns.

Probably as a reminiscence

to the romantic poem "The

Postillon" by Nikolaus Lenau

Mahler had originally used

the same name for this part

of the symphony. The fourth

movement "What man tells me"

is based on Friedrich

Nietzsche's "Also sprach

Zarathustra", the thoughts

and ideas of whom have awoke

strong interest among

musicians: At about the same

time Richard Strauss tried

to transform this

philosophical treatise into

a symphonic poem. Mahler,

however, was not familiar

with the usual form of

vocalisation. His excerpts

from Nietzsche`s text do not

really contain the basical

ideas of the "Zarathustra",

but reflect more or less his

own pantheistic ideology, in

which man is permanently

inflicted with nature. Being

performed by a "mysterious"

alto-solo, the deeply

philosophical character of

the text contrasts

strikingly to the

realistically depicted

paintings of the first three

movements; Mahler

intentionally wanted these

three movements to be

understood as humoresques.

According to Mahler only the

short fourth and the

monumental final movement

are meant very seriously.

Also the joyful-naive and

angel-like atmosphere of the

final movement with its

sound of bells and the

"Bim-Bam" of the boys' choir

are formed as a contrast to

that. Again the text is

taken from the collection of

"The boys magical horn",

which served as a source of

inspiation for his

symphonies again and again.

Its basical statement is the

assertion: "Have you not

followed the Ten

Commandments, fall down on

your knees. You must love

your only god for all time

and you will receive the

heavenly joy! The heavenly

joy is a sacred thing, a joy

that has no end." A naive

and believing parable on

god's love and goodness.

"In the Adagio, the final

movement, everything is

resolved into tranquility

and being" said Mahler; and

indeed, this Finale of half

an hour radiates an

unbelievable tranquility and

depth. In it, the highly

pantheistic view of life is

concretized to the highest

possible level; to Mahler it

meant the quintessencw of

his philosophy of life. In

his title sketches Mahler

has named it "What love

tells me". An explanation to

this can be found in a

letter to Anna von

Mildenburg, who interpreted

this love as more "worldly".

There he wrote: "But love in

this symphony is quite

different from your idea of

love. The slogan to this

movement reads: Father, see

my wounds! Let no being be

lost!

Do you understand now, what

I meant by this? It is to

signify the top and the

highest level from which our

world can be seen. One could

also call this movement What

God tells me, but only

in the sense that god can he

won by love only. And thus

my work forms a musical poem

that depicts all stages of

the evolution in a

step-by-step gradation. It

begins

with lifeless nature and

culminates in the love of

god."

|

|

|