|

|

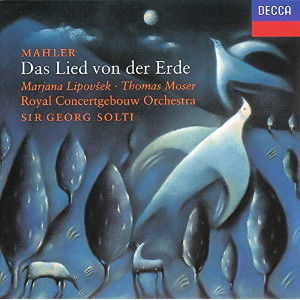

1 CD -

440 314-2 - (p) 1994

|

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Das

Lied von der Erde |

|

62' 58" |

|

| - 1. Das Trinklied

vom Jammer der Erde |

8' 11" |

|

|

| - 2. Der Einsame im

Herbst |

9' 43" |

|

|

| -

3. Von der Jugend |

3' 00" |

|

|

| -

4. Von der Schönheit |

6' 49" |

|

|

| -

5. Der Trunkene im Frühling |

4' 23" |

|

|

| -

6. Der Abschied |

30' 20" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Marjana

Lipovšek, mezzo-soprano

|

|

| Thomas Moser,

tenor |

|

| Royal

Concertgebouw Orchestra

|

|

| Georg SOLTI |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Grotezaal,

Concertgebouw, Amsterdam (Olanda)

- dicembre 1992 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live |

|

|

Producer |

|

Michael

Haas |

|

|

Engineers |

|

James

Lock, Colin Moorfoot |

|

|

Tape editor |

|

Sally

Drew |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Decca

| 440 314-2 | (1 CD) | durata 62'

58" | (p) 1994 | DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

The

Decca Record Company Limited,

London

|

|

|

|

|

Each of

Mahler’s symphonies

represents a stage in his

life; together they form a

kind of spiritual

autobiography. The young,

romantic hero of the First

Symphony, feverishly

endorsing life, is made to

confront the larger issues

of death and resurrection in

the Second. The end of that

work is a declaration of

faith in the Christian God,

and the Third and Fourth

Symphonies go on to present

a pantheistic vision of the

chain of creation. In the

Third this culminates in the

love of God; in the Fourth,

the innocence of the child.

The middle-period

symphonies, Nos. 5-7,

present the battle of life

in more purely human terms.

Love is no longer idealised

but focused on an

individual: his wife, Alma.

The Fifth and Seventh

Symphonies end triumphantly;

the Sixth, after a

tremendous struggle, ends in

stark tragedy: it is a work

full of premonitions of

death. Mahler sought to

overcome his doubts in a

massive reaffirmation of

religious belief: the Eighth

Symphony. Here, too, Alma

has a supreme place, as

Goethe's Eternal Feminine

who leads man towards God.

The end of the Eighth unites

secular and religious themes

in an unprecedented

splendour of orchestral

sound.

Das Lied von der Erde

(The Song of the Earth),

which Mahler called a

symphony, though he did not

include it in his canon,

inhabits an entirely

different world. In the

summer of 1907 all his

forebodings came to pass. He

was told that the condition

of his heart was such that

he probably had only a few

more years to live. At the

same time his elder daughter

Maria died, and he was

forced to resign from the

directorship of the Vienna

opera. In a letter to the

conductor Bruno Walter he

wrote: 'At a single fell

stroke I have lost any calm

and peace of mind I ever

achieved. I stand vis-à-vis

de rien, and now, at the end

of my life, I have to begin

to learn to walk and stand.'

Beginning again forced

Mahler to turn inward: Das

Lied von der Erde and

the Ninth Symphony are the

most introspective of all

his works. The Chinese poems

he found in Hans Bethge's

volume Die chinesische

Flöte (The Chinese

Flute), which was then

greatly in vogue, expressed

what he felt, both in their

pessimism (more extravagant

in Bethge's versions than in

the Chinese originals) and

in their poignant insights

into the transient beauty of

nature and human life.

Characteristically, Mahler

in places altered Bethge's

texts (as he did with

virtually all the texts he

set). In particular, the

final, consoling lines of

'Der Abschied', which speak

of the earth renewing itself

in spring, are entirely his.

Bethge's poems were not

direct translations from the

Chinese but largely derived

from earlier German versions

by Hans Hellmann, which were

themselves based on French

versions by Judith Gautier

(Wagner's last mistress) and

Hervey-Saint-Denys. In two

cases - 'Der Einsame im

Herbst' and 'Von der Jugend'

- no Chinese originals can

be traced, and it is

probable that they are

pieces of chinoiserie by

Gautier herself. The other

four poems have acquired a

veneer of late-Romantic

embellishment which makes

them quite remote from their

sources. Similarly with

Mahler's musical language:

the pentatonicisms of

movements three to five are

merely an exotic element in

what is a quintessentially

late-Romantic score.

Mahler's predicament - for

he now felt he was writing

on the brink of death -

gives the music of Das

Lied von der Erde a

new clarity and urgency, and

its emotional pitch is at

times almost unbearably

intense.

The A minor of the first

movement, the 'Trinklied',

recalls the Sixth Symphony

and looks forward to the

Rondo Burleske of the Ninth.

Mahler reserved A minor for

his darkest statements. The

falling refrain of the

'Trinklied' - 'Dunkel ist

das Leben, ist der Tod' - is

also closely related to a

phrase in the first movement

of the Sixth. But instead of

a battling march we have a

frenetic, one-in-a-bar waltz

which sweeps all before it.

Only in the central

orchestral interlude does

the grim mood soften: a

trumpet rises ecstatically

to a high C, and the tenor

sings of the eternal blue of

the sky. The recapitulation,

at 'Seht dort hinab!',

restores A minor with a

vengeance, Mahler making

telling use of the basic

sonata structure to

emphasise the inescapability

of his main key. The final A

minor thud is like a coffin

slammed shut.

Whereas the emotional scale

of the 'Trinklied' is

frighteningly large, 'Der

Einsame im Herbst', the slow

movement, is intimate and

restrained. The

chamber-music textures are

close to the middle songs of

the Kindertotenlieder.

Only once, at ‘Sonne der

Liebe', does the

mezzo-soprano's voice rise

up in passion. The next

three movements are short,

contrasting scherzos, the

first two delicate genre

pictures like willow-pattern

plates, though 'Von der

Schönheit' has a rowdy

middle section depicting a

party of young horsemen. The

boisterousness of this music

is carried over into the

next movement, ‘Der Trunkene

im Frühling', which ends

with the most desperately

exuberant passage of the

work, in A major, rounding

off what may be seen as the

first part of the symphony.

The last movement, 'Der

Abschied', is nearly as long

as the other five together,

and is one of the greatest

movements Mahler ever wrote.

It is in C minor, the key of

the huge opening funeral

march of the Second

Symphony, and the two poems

Mahler set are separated by

another funeral march,

gravely eloquent. In the

long C major coda -

infinitely long, as one

imagines (and hopes) that

the mezzo-soprano's 'ewig's’

will never cease - the

endless yearning of Das

Lied von der Erde

finds some haven of rest,

not in a Liebestod

but in a surrendering of

self to the healing power of

the natural world. Nature,

at least, was for Mahler a

never-failing source of

comfort.

© David

Matthews

|

|