GEORG

SOLTI & THE CHICAGO

SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

Fifteen years

were destined to separate

Georg Solti’s debut as a

guest leader of the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra - at

summer concerts of the

Ravinia Festival - and his

first Orchestra hall

appearance, downtown, as

music director in the autumn

of 1969 The first encounter,

however, in 1954, was

instantaneously productive

of a mutual respect and

rapport that deepened with

each subsequent interim

meeting. No matter who was

resident conductor in

Chicago, or what traditions

variously prevailed whenever

Solti would return as a

guest, the orchestra each

time became his ally-as such

the mirror of a singular

aesthetic temperament in our

time. The precision that

Solti has always demanded in

musical performance (as an

essential for musical

expression) has been his to

command in whatever

capacity, under whatever

circumstances, at whatever

time.

With his

appointment as music

director, thereby continuing

an artistic heritage

hand-fashioned by Artur

Rodzinski (1947-48) and

Fritz Reiner (1953-63), the

alliance of conductor and

orchestra has produced a

synchronous artistry without

parallel in Chicago’s

musical history. By no means

is this said to

underestimate the

achievements of Solti’s

predecessors, without the

finest of them he would not

now have the superlative

assembly at his summons. But

none before him in memory -

and some before him

possessed awesome powers -

could quite persuade the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

to give so eloquently of

themselves at the same time

as they sustained such a

high level of discipline.

Early on this interaction of

a great conductor and a

great orchestra surpassed

such essentially irrelevant

concerns as love for one

another.

Respect and

rapport are the rudiments of

Georg Solti’s astounding

achievement to date in

Chicago, as documented on

these discs for the first

(but surely not for the

last) time. To some persons,

as the years lengthened into

a decade, and beyond, it may

have seemed that the

eventual union of Georg

Solti and the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra was not

meant to be. But to others

of us, the long wait served

instead to whet the appetite

further for what promised,

on each visit, to be an

artistic inevitability - and

has indeed proved to be,

altogether beyond

expectations.

notes by

DERYCK COOKE

Mahler’s whole

life-work as a symphonist

can be described as a search

for an identity - which is

no doubt why his music makes

such a strong appeal to us

today, and especially to the

young.

Symphonic

music before Mahler was

written by composers who

felt themselves part of a

stable environment - men

able to take for granted the

basic assumptions of their

society, if only to rebel

against them. Even Mozart,

who had to struggle so

desperately against the

musical conditions of

eighteenth-century Austria,

did at least have this

immovable wall to beat his

head against in vain. But in

Mahler we find the first

symphonist who represents

that typical modern figure,

the man who is uprooted and

out of his element. As an

Austrian Jew born in

Bohemia, he was technically

a member of the Germanic

civilisation, but he often

used to say, according to

his wife’s memoir of him: ‘I

am three times homeless, as

a native of Bohemia in

Austria, as an Austrian

amongst Germans, and as a

Jew throughout all the

world: everywhere an

intruder, never welcomed’.

In

consequence, there was

nothing stable for him in

any of his environments, and

his work became an

unremitting quest to

discover some stable

attitude with which to

identify himself. This

involved a good deal of

chopping and changing, even

in his everyday life, as

another quotation from his

wife’s memoir shows: ‘It was

... out of the question for

me to say “But Gustav, you

said the very opposite

yesterday” (as he often

did), because he reserved

for himself the privilege of

inconsequence. This

characteristic of his was

often a great shock to me. I

could never be sure what he

thought and felt’. No doubt

Mahler himself couldn’t

always be sure himself,

either.

It is this

which explains that strange

and often-criticised element

of theatricality in Mahler’s

music. Frequently, when he

expresses a certain state of

mind, it is not out of

permanent conviction, but

out of an unconscious need

to identify himself

with that state of mind, to

believe in it passionately

for the moment, in the hope

that it may prove a valuable

one to cling to, and remain

an abiding acquisition; yet

there is always his acute

intellect, unable not to

look on from outside, and

weigh up the situation, and

consider whether the state

of mind is in fact as

valuable and fruitful as it

seems. He struggled with

this situation for long:

only from The Song of

the Earth onwards,

when he was faced with

certain premature death, did

he begin to find his way out

of it, in resigned

reconciliation with the

inescapable transience of

human life. Before that

work, each spiritual world

that he built up over a

period, and embodied in a

symphony, afterwards

vanished, as if it had never

been: each new symphony till

then was a fresh start, a

start from scratch. As Bruno

Walter said: ‘No spiritual

experience, however hardly

won, was ever his secure

possession’.

Aaron Copland

- who admires Mahler’s music

- has taken a more critical

view. ‘The difference

between Beethoven and

Mahler’, he says, ‘is the

difference between watching

a great man walk down the

street and watching a great

actor act the part of a

great man walking down the

street’. It is easy to see

what Gopland is driving at -

the manifest element of

impersonation in much of

Mahler’s music - but he does

not go deep enough to

explain why this should be.

There is nothing superficial

or insincere about Mahler,

but only an underlying

psychological instability.

The real difference between

Beethoven and him is that

between watching a great man

walk down a street in which

he feels himself secure, and

is therefore perfectly at

ease with his greatness, and

watching a great man walk

down a street in which he

feels himself totally

insecure, and is therefore

obliged to act out his

greatness, self-consciously

and defiantly - because he

is scarcely able to credit

it in his heart of hearts,

uncertain whether the street

will not suddenly cease to

be a reassuring background

and become hostile territory

in which he will be an

outcast.

Mahler had to

walk down so many streets,

and felt at home in none of

them; and this is the

fundamental origin of the

almost disruptive contrasts

in his music. With each new

symphony - and sometimes

with each new movement

inside a symphony - we are

taken into a different

world. In each case there is

a passionate, even desperate

identification with a

certain attitude - but only,

in the last resort, for what

it is worth, suddenly the

scene changes, and another

attitude is being identified

with - but again only for

what it is worth. In the

first four symphonies we

find Mahler striving to

identify hirnself with four

different kinds of idealism:

The power of the will

against fate in the first,

the Christian belief in

resurrection in the second,

a dionysiac pantheism based

on Nietzsche in the third,

the indestructibility of

innocence in the fourth.

Into all these symphonies

the youthful lyricism of

Mahler’s early songs enters,

either in instrumental

arrangements or else

actually sung by voices -

the voices of children, or

of adults possessed of a

childlike, trusting faith.

None of these

idealistic worlds proved a

haven to rest in, and the

Fifth Symphony, completed in

1902 at the age of

forty-two, brought a more

than usually determined

wiping of the slate. It

marks the beginning of

Mahler’s full maturity,

being the first of a trilogy

of ‘realistic', purely

instrumental symphonies -

Nos. 5, 6 and 7 - which

occupied him during his

middle period. Gone are the

programmes, the voices, the

songs, and the movements

based on songs, and the

delicate or warm harmonic

sonorities which formerly

brought relief from pain

have been largely replaced

by a new type of naked

contrapuntal texture,

already foreshadowed in

parts of the Fourth

Symphony, but now given a

hard edge by the starkest

possible use of the woodwind

and brass.

In the Fifth Symphony,

although it has no actual

programme, there are two

manifest and utterly opposed

attitudes which are set side

by side, with so little

reconciliation between them

as to threaten the work with

disunity. The Symphony might

almost be described as

schizophrenic, in that the

most tragic and the most

joyful worlds of feeling are

separated off from one

another, and only bound

together by Mahler’s

unmistakable musical

personality, and his

extraordinary command of

large-scale symphonic

construction and

unification.

The first of

the work’s three parts

consists of the two opening

movements: linked

emotionally and

thematically, they explore

to the full the tragic view

of life, and give only a

late and fleeting glimpse of

the opposite view - that of

triumphant life-affirmation.

The first movement is a

black funeral march in C

sharp minor, beginning with

a hollow trumpet fanfare in

the minor mode, which is to

strike in at various focal

points as a kind of iron

refrain. Curiously enough,

this beginning stems from a

passage in the Fourth

Symphony, as though Mahler

wanted to preserve at least

a thread of continuity

between his new ‘realistic’

world and the world of naive

innocence he had just left

behind. The minor-mode

trumpet fanfare had already

appeared at the one really

bitter juncture of the

Fourth - the nightmarish

collapse of the development

section of its first

movement - and at the same

pitch of C sharp minor, far

removed from the movement’s

main tonality of G major:

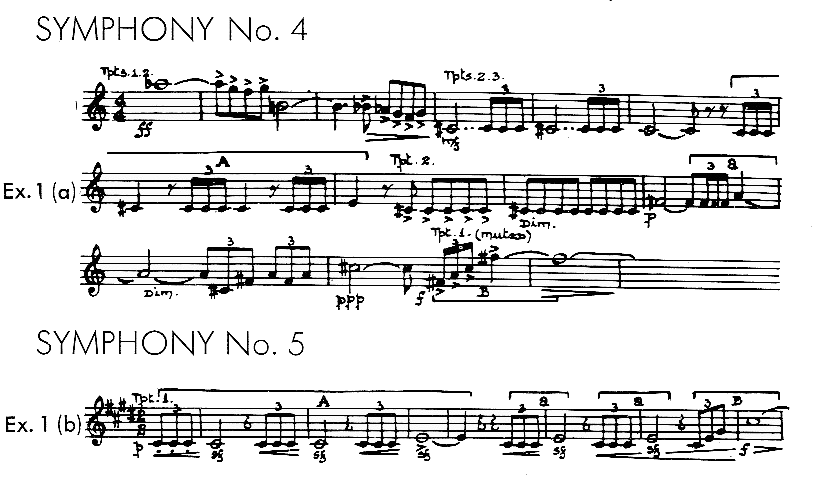

The opening

movement of the Fifth

alternates its main slow

funeral-march music with

ferocious outbursts of

grievous protest in a faster

tempo; and the first of

these starts with a

three-note phrase

(marked which is

to be the chief means of

unifying the two opening

movements:

The phrase

becomes pervasive, and

towards the end of the

movement it appears in a new

accompanying form, in the

key of A minor which is to

be that of the second

movement:

And this form

of the phrase also pervades

the opening allegm material

of the second movement,

eventually acting as the

starting point-point of its

main theme:

The A minor second movement

is frenetic, and it reverses

the situation of the first:

the ferocious mood of

protest is basic, and there

are slower sections which

are related to the

funeral-march music of the

first movement - not only in

mood, but in some of the

actual thematic material. It

is, however, the phrase X

which is the chief unifying

factor, and at four separate

points it turns to the major

mode which is to dominate

the remaining three

movements of the Symphony.

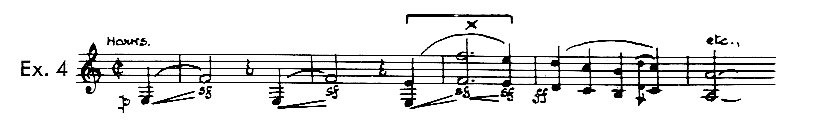

The first time (Ex. 5a), it

introduces one of the

reminiscences of the first

movement, bringing back the

consoling secondary idea of

the funeral-march music; a

little later (Ex. 5b), it

introduces a cheerful

popular-type march-tune of

deliberate, sarcastic

triviality, a little later

still (Ex. 5c), it flashes

through the prevailing

darkness a vivid blaze of

light which is immediately

eclipsed; and finally, a

good deal later (Ex. 5d), it

brings the climax of the

movement - a noble

chorale-like passage in the

actual key of D

major in which the Symphony

will settle from the third

movement onwards.

It will be noticed that,

from 5b onwards, figure X

rises higher all the time: F

and E flat in 5b, F sharp

and E natural; followed by G

sharp and F sharp in 5c; and

finally, reaching a peak in

D major, A and G in 5d. And

this last passage culminates

in a chorale-like theme,

which looks out across the

rest of the Symphony to the

finale, of which it is to be

the final climax:

For the time

being, however, this too is

eclipsed, and the movement

eventually dies away

shadowily in A minor, the

despairing last word being

with its main theme, based

on the figure X:

So ends the

tragic first part of the

Symphony. The second part

consists of the third

movement only - the big

Scherzo - and the moment it

begins, the schizophrenic

character of the work

emerges. It completely

contradicts the nihilistic

mood and minor tonality of

practically everything that

has gone before, by

switching to the brilliant

key of D major, and to an

exploration of the joyfully

affirmative view of life,

both of which are to occupy

the rest of the Symphony.

Thus the dark world of Part

I is not gradually dispelled

by a process of spiritual

development: it is abruptly

rejected in favour of a

completely different

attitude. The tragic view of

life is one way of looking

at things, the Symphony

seems to say, and this is

another: the two different

attitudes are always there,

and either or both may be

right - but it is impossible

to reconcile them.

Nevertheless,

since they are being

presented in a work of art -

a symphony - they are

provided with the necessary

musical unification: not

only through the eventual

reappearance of the

chorale-theme of Ex. 6 near

the end of the finale, but

also at the very outset of

this third movement. Part I

of the Symphony, as we have

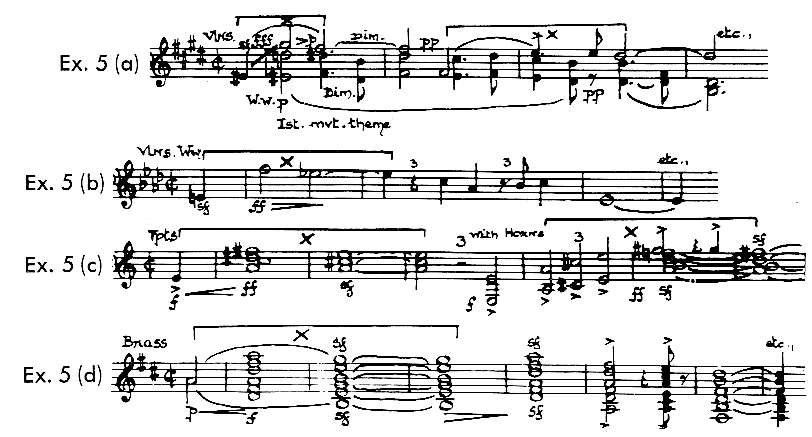

seen, ended with a

despairing reference to the

main theme of the second

movement (Ex. 7), based on

the chief unifying figure,

X; and if we transpose this

reference from A minor to

the new key of D major (Ex.

8a), it stands clearly as

the basis of the joyous

opening horn-theme of the

new movement which is Part 2

(Ex. 8b - see asterisks).

This Scherzo is a

symphonic Ländler,

with an ebullient

obbligato part for the

first horn-player of the

orchestra. Admittedly, the

waltz-like trio-section

brings a mood of

nostalgia; and there is an

awesome climax with horns

echoing and re-echoing

across mountain distances,

which leads to haunting

music full of sadness and

loneliness. But these

passages have nothing

emotionally in common with

the despairing laments of

the first part of the

work; and in any case,

they are subsidiary to the

excited Ländler music,

which returns all the

time, in rondo fashion,

and eventually brings the

movement to a jubilant

ending. The Scherzo is

really a dance of life,

evoking all the bustle of

a vital existence, as

opposed to the

concentration on the

inevitability of death in

the funeral marches and

ferocious protests of Part

I.

The third

and final part of the

Symphony consists of the

last two movements. First

comes the famous Adagietto

for strings and harp only,

which is a quiet haven of

peace in F major between

the strenuous activity of

the D major Scherzo and

the equally strenuous

activity of the D major

Finale. Pervaded with the

familiar romantic mood of

withdrawal from the strain

and tension of life into

the quietude of the inner

self, the Adagietto

has much in common with

Mahler’s great song Ich

bin der welt abhanden

gekommen (I am lost

to the world), which ends

with the words ‘I live

alone, in my own heaven,

in my love, in my

singing’. And this

movement too is related

symphonically to all that

has gone before, by its

use of the chief unifying

figure, X. Its main theme

can be shown to be based

on the figure, but more

striking is the threefold

quotation of it at the

crucial point when the

movement switches suddenly

to the new and ecstatic

key of G flat major:

Out of this

movement’s quiet retreat,

the Finale emerges

immediately - and

magically. A single

horn-note, like a call to

awake, is answered by a

drowsy echo on the

violins, which is in fact

a repetition of their

last, long-drawn, peaceful

note in the Adagietto:

the Symphony is unwilling

to turn from meditation to

action. The note is A, the

third degree of the Adagietto

key of F major; but it now

stands as the dominant

(fifth degree) of D major,

switching the Finale back

to that main key of the

last two parts of the

Symphony. Various

fragments of cheerful

folk-like melody are given

out straight away by

unaccompanied woodwind

instruments and horn,

providing much of the

thematic material of the

movement. The first quick

one on the bassoon was

taken by Mahler from his

satirical Wunderhorn

song Lob des hohen

Verstandes about the

singing-contest in which

the cuckoo beat the

nightingale because the

donkey acted as the judge;

but the second and third,

on clarinet and bassoon

respectively, may sound

even more familiar in the

present context. They are

in fact speeded-up

versions of the two

separate segments of the

big chorale-theme of the

second movement - as

becomes clearer when,

after the horn has

introduced another idea,

the clarinet plays both

segments continuously (cf.

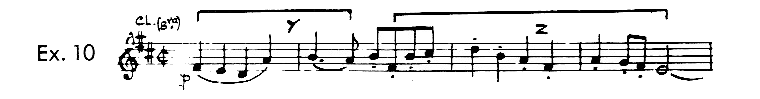

Ex. 6, figures Y and Z):

The last

four notes of this theme

immediately become the

starting-point of the

Finale’s main rondo tune,

given out by horns and

strings: the mood is again

joyful and exuberant, but

this Finale - like that of

Beethoven’s Eroica

- brings the symphony to a

vital culmination which is

concerned, not so much

with the expression of

particular life-attitudes,

as with the composer’s

artistic joy in symphonic

creation, of building up a

large musical structure.

It thus follows naturally

on the Adagietto,

the haven of recuperation

from life’s turmoil; and

this is further emphasised

by the use of an actual theme

from the Adagietto,

at a quicker tempo, as the

Finale’s second subject.

Mahler’s structure is a

huge one, combining sonata

and rondo, and including,

as part of the opening

group of themes, a fugal

exposition on a bustling

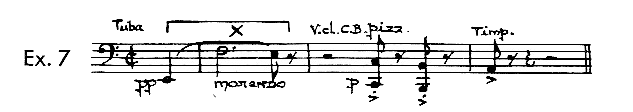

subject. The final climax,

before the Symphony races

away to its cock-a-hoop

conclusion, is a full

restatement of the big

brass chorale introduced

so fleetingly towards the

end of the second movement

(Ex. 7, via Ex. 10).

Ultimately - and

notwithstanding the subtle

unifying power of the

ubiquitous figure X - it

is this explicit

cross-reference between

the most anguished

movement in Part I and the

most joyous movement of

Part 3 which is the main

cross-beam holding

together the dangerously

disparate elements of

total darkness and total

light at either end of the

Symphony.

Mahler’s use

of a phrase from his song

Lob des hohen

Verstandes as a

motive in the Symphony’s

finale, mentioned above,

was the last (and least)

quotation of this kind

that he made. Earlier, he

had drawn on other songs

from the same collection -

the settings of poems from

the German folk-anthology

Des Knaben Wunderhorn

(The Boy’s Magic Horn) -

for whole movements, or

sections of movements, in

his second, third and

fourth symphonies. The

songs on the fourth side

of the present issue, also

from this collection, were

not drawn on for the early

symphonies; though

curiously enough, two of

them were to have faint

repercussions in the Tenth

(much as a phrase from the

last of the Kindertotenlieder,

is hinted at in the finale

of the Sixth). The voice’s

initial yodelling phrase

in Verlorne Müh’ -

in the form it takes at

the opening of the second

verse - is identical with

the initial phrase of the

Ländler-like trio-section

of the Tenth’s first

scherzo; and the sinister

ostinato accompaniment of

Das irdische Leben

has something in common

with the sinister ostinato

accompaniment of the

symphony’s ‘Purgatorio’

movement.

|