|

|

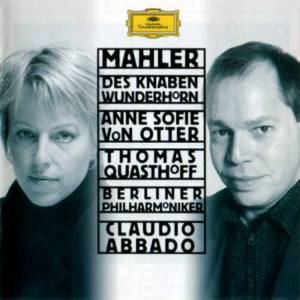

1 CD -

459 646-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

| GUSTAV MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Des

Knaben Wunderhorn |

|

57' 04" |

|

-

1. Revelge **

|

7' 13" |

|

|

-

2. Rheinlegendchen *

|

3' 21" |

|

|

- 3. Trost im

Unglück **

|

2' 22" |

|

|

-

4. Verlorne Müh' *

|

2' 42" |

|

|

- 5. Der

Schildwache Nachtlied **

|

6' 10" |

|

|

-

6. Das irdische Leben *

|

2' 52" |

|

|

-

7. Lied des Verfolgten im Turm **

|

3' 56" |

|

|

-

8. Wer hat dies Liedlein erdacht? *

|

2' 05" |

|

|

-

9. Des Antonius von Padua

Fischpredigt **

|

4' 03" |

|

|

-

10. Lob des hohen Verstandes **

|

2' 32" |

|

|

-

11. Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen

*

|

7' 11" |

|

|

-

12. Der Tamboursg'sell **

|

6' 53" |

|

|

-

13. Urlicht *

|

5' 44" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anne Sofie von Otter,

Mezzosopran *

|

|

Thomas Quasthoff,

Bariton **

|

|

| Berliner

Philharmoniker |

|

| Claudio ABBADO |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Großer

Saal, Philharmonie, Berlin

(Germania) - febbraio 1998 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Produced by |

|

Dr.

Marion Thiem |

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Reinhard

Lagemann |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer)

|

|

Ulrich

Vette |

|

|

Editing |

|

Reinhild

Schmidt, Matthias Schwab |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 459 646-2 - (1 CD) -

durata 57' 04" - (p) 1999 - 4D DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Cover Photo: Mats

Bäcker (von Otter), Susesch

Bayat (Quasthoff) |

|

|

|

|

In the summer

of 1893, while he was seting

the Wunderhorn text

"Rheinlegendchen" to music,

Mahler was asked by his

confidante Natalie

Bauer-Lechner how he

composed. "It happens in a

hundred different ways", he

responded. "Today, for

instance, I had a theme in

mind; I was leafing through

a book and soon came upon

the lines of a charming song

that would fit my rhythm.

[...] It is [...] direct but

whimsically childlike and

tender in a way that you

have never heard before.

Even the orchestration is

sweet and sunny - nothing

but butterfly colours." (We

know that Mahler thought of

his Wunderhorn and

Rückert songs as a kind of

vocal chamber music,

involving orchestral

resources and an acoustic

appropriate to that concept

and its harmony.) "But", he

continued, "in spite of all

its simplicity and folklike

quality, the whole thing is

extremely original,

especially in its

harmonization, so that

people will not know what to

make of it, and will call it

mannered. And yet it is the

most natural thing in the

world; it is simply what the

melody demanded." Three

years later, in the summer

of 1896, Natalie relates,

Mahler composed Lob des

hohen Verstandes:

"'Here', he said to me, 'I

merely had to be careful not

to spoil the poem and to

convey its meaning exactly,

whereas with other poems one

can often add a great deal,

and can deepen and widen the

meaning of the text through

the music'."

The majority of Mahler's

orchestral Wunderhorn

songs were composed between

1892 and 1898 and published

in 1899; two last settings,

Revelge and Tamboursg'sell,

were made in 1899 and 1901

respectively. About the

latter song, Mahler spoke to

Natalie Bauer-Lechner in the

summer of 1901: "[Der

Tamboursg'sell] -

almost as if according to a

pre-established harmony

between notes and words -

came into being as follows.

It occurred to him literally

between one step and the

next - that is, just as he

was walking out of the

dining-room. He sketched it

immediately in the dark

ante-room, and ran with it

to the spring - his

favourite place, which often

gives him aural inspiration.

Here, he had the music

completed very quickly. But

now he saw that it was no

symphonic theme - such as he

had been after - but a song!

And he thought of 'Der

Tamboursg'sell'. He tried to

recall the words; they

seemed made for the melody.

When he in fact compared the

tune and the text up in the

summer-house, not a word was

missing, not a note was

needed. They fitted

perfectly!"

Mahler drew his texts for Des

Knaben Wunderhorn from

that famous anthology of

"old German songs",

collected by Achim von Arnim

and Clemens Brentano and

first published in three

volumes in 1806 and 1808.

The Wunderhorn

collection was, as Dika

Newlin once put it, a

"typical product of the

romantic Zeitgeist,

with its stress on the

semple, artless life of the

'little people' and the

glamour of bygone days". One

reason for the anthology's

popularity was its appeal to

the 19th century's nostalgic

yearning after the lost

innocence of a remote past.

Mahler's approach in his

orchestral settings (he had

already made use of Wunderhorn

poems in two volumes of his

early Lieder und Gesänge

with piano) was, however,

stubbornly independent of

this romantic indulgence. He

eschewed all false

medievalism and

self-conscious "folkiness"

(there are no folk-tune

quotations, references or

"arrangements" in Mahler's Wunderhorn

songs) and simply accepted

the texts at their face

value. He did not adopt a

fairytale, "once upon a

time" approach to the texts,

but relived them as if they

were of the present moment.

The reality - the immediacy

and dramatic or lyrical

truth - og his settings,

their well-nigh

anti-romantic character, is

what lends them their

singular flavour.

It is possible to divide Des

Knaben Wunderhorn,

roughly, into three

contrasted groups: 1. songs

which are marches or

pervaded by military imagery

(fanfares and the like); 2.

songs which are primarely

lyrical in tone (often love

songs); and 3. humorous

songs. (Urlicht,

which was incorporated intho

the Second Symphony, is

mystical and religious in

spirit and thus belongs to a

group on its own.) Into

group one fall Revelge,

Der Tamboursg'sell, Der

Schildwache Nachtlied

and Wo di schönen

Trompeten blasen - and

at once we are aware of the

impracticality of the

grouping. True, all four

songs are rich in references

to the military music with

which Mahler had been

familiar since childhood,

and which he continued to

hear on the streets about

him, but the third and

fourth songs, in which

fanfares and march rhythm

are contrasted with passages

of the tenderest lyricism,

also have a foot in group

two, which comprises Verlorne

Müh', Trost im

Unglück, Das

irdische Leben, Rheinlegendchen

and Lied des Verfolgten

im Turm. Here again

the consistency of the

grouping does not really

stand up to close scrutiny.

How can we accomodate under

one heading the teasing

character of the first song,

the lilting geniality of the

fourth, the plaintiveness of

the third, and the drama and

impetuosity of the second

and fifth? The last, indeed,

is a miniature dramatic

"dialogue", a form that

occurs more than once. And

in the same way, we find in

group three the good humour

of Wer hat dies Liedlein

erdacht? juxtaposed

with the caustic wit of Lob

des hohen Verstandes

(wich Mahler conceived as a

hit at his critics, and

which anticipates a leading

idea in the finale of the

Fifth Symphony) and the

pungent irony of the Fischpredigt

(the basis of the Second

Symphony's scherzo).

Another feature of Mahler's

Wunderhorn setting,

their extraordinary harmonic

invention, is exemplified by

the very last bars of Der

Schildwache Nachtlied,

that ghostly ballad which at

ist very end fades with a

ravishing poignancy into

nothingness, like the

spectre of Hamlet's father

with the coming of dawn.

Mahler accomplishes this

stunning effect by leaving

his song - and his

performers and his audience

- suspended on the

unresolved dominant. It is a

transfixing moment, and a

bold technique to have

deployed in the early 1890s.

The critic and author Ernst

Decsey tried once, in a

conversation with Mahler, to

draw the composer out on

this passage, commenting on

"a remarkable evolution of

the dominant chords that

produced an ever-rising

tension". But Mahler

"refused to take the point":

"Oh, go on! Just accept

things with the simplicity

with which they're

intended." "Simple" it may

be, in the effect it makes;

but it is a simplicity that

strikes deep, of the kind

that only genius has at its

command.

Finally, a word about

Mahler's last two Wunderhorn

settings, Revelge

and Der Tamboursg'sell,

which were published

independently of the rest.

The sheer scale of these

songs speaks for itself, as

does the high profile

allotted the orchestra

alone. Each song inhabits a

unique sound-world, a

consequence of the

orchestra's transformation

into something corresponding

to a military wind band.

Percussion is prominent. In

Revelge, a vocal

march of epic proportions,

the strings themselves are

used as a percussive

resource, while in Der

Tamboursg'sell only

the lower strings -

execlusively cellos and

double basses - are

employed. The intensity of

his music has few parallels,

even elsewhere in Mahler.

These final, late-style Wunderhorn

settings, fertilized by

Mahler the symphonist,

remind us again of one

central truth about his

approach to his texts: that

for Mahler the poems were

not artificial evocations or

revivals of a lost age of

chivalry and German

romanticism but, with the

exception of a few genial,

sunny inspirations, vivid

enactments of reality - of

sorrow, heartbreak, protest,

terror and pain. His Wunderhorn

songs often report a

chilling trith about the

human condition.

Donald

Mitchell

|

|

|