|

|

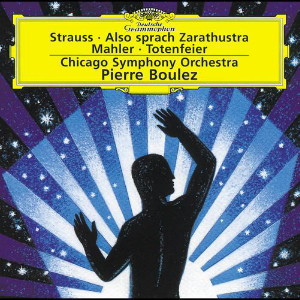

1 CD -

457 649-2 - (p) 1999

|

|

| RICHARD STRAUSS

(1864-1949) |

|

|

| Also

sprach Zarathustra |

33'

26" |

|

| -

Einleitung |

2'

02" |

|

| -

Von den Hinterweltlern |

4'

03" |

|

| -

Von der großen Sehnsucht |

2'

01" |

|

| -

Von den Freuden und Leidenschaften |

1' 47" |

|

| -

Das Grablied |

2' 04" |

|

| -

Von der Wissenschaft |

4' 13" |

|

-

Der Genesende

|

4' 11" |

|

| -

Das Tanzlied |

7' 49" |

|

| -

Nachtwandelerlied |

4' 16" |

|

|

|

|

| GUSTAV MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

| Totenfeier |

28'

56" |

|

-

Maestoso - Höchste Kraft -

Zurückhaltend - Meno mosso - Sehr

mäßig beginnend - Tempo I -

Feierlich und langsam - Immer etwas

langsamer - Allegro

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Chicago

Symphony Orchestra |

|

| Pierre Boulez,

Conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Orchestra

Hall, Chicago (USA) - dicembre

1996 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive Producer |

|

Roger

Wright |

|

|

Recording Producer |

|

Karl-August

Naegler |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Ulrich

Vette |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Jobst

Eberhardt |

|

|

Editing |

|

Dagmar

Birwe |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 457 649-2 - (1 CD) -

durata 58' 45" - (p) 1999 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Cover

Illustration: Pham van Mz, c/o

Margarethe Hubauer

|

|

|

|

|

It

is characteristic of Mahler

that well before completing

the jubilant D major

conclusion of his First

Symphony he had already

launched its polar opposite'

“Totenfeier” ("Funeral

Rite,”

or literally "Death

Celebration”), the grim C

minor movement that would

eventually serve as the

opening of his Second

Symphony, the “Resurrection.”

As so often in his career,

the impulse to compose was

intertwined with personal

experience. "My

music is lived," he

once said, and so it was with

“Totenfeier.” In

January of 1888 Mahler, then

assistant conductor at the Leipzig

opera, had realized his

first public success as a

composer (or, more

precisely, co-composer) by

transforming the sketches

for Carl Maria

von Weber’s

unfinished Die drei

Pintos into a

three-act opera that would

remain in the repertoire for

many years. Immediately

after the Pintos

premiere he began work on

the opening funeral march of

"Totenfeier"

and was seized by one of the

uncanny visions that

periodically gripped him: as

his confidante and

chronicler Natalie

Bauer-Lechner reports, “he

saw himself lying dead upon

a bier under wreaths

and flowers (which were

in his room from the

performance of the Pintos)

until Frau von Weber quickly

removed all the flowers from

him." Marion

von Weber was the wife of

Carl Maria

von Weber's grandson; during

the Pintos

project she and Mahler

fell in love. From vaious

sources we know

that this Werther-like

affair brought enormous

strain to all three parties,

yet it also inspired Mahler

to compose at white-hot

speed.

He probably adopted the

title “Totenfeier” from a

fragmentary dramatic epic by

the 19th-century Polish poet

Adam Mickiewicz,

which appeared in

1887 in a German translation

by Mahler’s

longtime friend and mentor

Siegfried Lipiner (who also

provided a lengthy

introduction). In one

section of the poem the

protagonist, Gustav [!], has

committed suicide after the

marriage of his beloved, Marie,

to another suitor,

Thereafter Gustav's spirit

is condemned to wander

in the vicinity of his

inamorata and becomes, in Lipiner’s

view,

“a Werther sub specie

aeternitatis [under

the aspect of eternity]." Indeed,

in Lipiner’s reading,

Gustav's suicide represents

nothing less than “the Fall

of man and his

punishment.” Thus it seems

hardly coincidental that in

the second half of the

"Totenfeier"’s

development section Mahler

quotes

the "Dies

irae" ("Day

of wrath")

chant, which

was

obligatory in settings of

the Requiem

Mass

prior to Vatican

II. It is

heard shortly

before the movements

shattering dissonant climax,

an unforgettable denouement

based on musical rhetoric

from the third of Mahler’s

Lieder eines fahrenden

Gesellen

(Songs of a Wayfarer),

his earlier cycle on the

theme of unrequited love.

The song is entitled “Ich

hab’ ein glühend

Messer”

(“I

have a burning knife”), and

the text with

its explicitly suicidal

subject is by the composer

himself.

Since their student days,

both Mahler

and Lipiner

had embraced a viewof

tragic art and redemption

derived from the

philosophical writings of

Schopenhauer, Wagner and

Nietzsche, according to

which Promethean defiance

leads toward

self-transcendence

and redemption. So much is

apparent from the lines of

poetry - again the

composer's own -

with which Mahler

at long last concluded his

romantic and idiosyncratic

fresco of Doomsday and

Resurrection in the Second

Symphony's finale, more than

six years after beginning work

on the "Totenfeier"

movement. Although Mahler

apparently never fully

abandoned his original plan

to place "Totenfeier"

at the head of a multi-movement

symphony, during those six

years he campaigned for its

separate performance and

publication (in both cases

unsuccessfully).

The score performed on this

recording is that of his

autograph manuscript dated 10

September 1888 (and partly

revised not long

thereafter), as published in

the Critical Edition of Mahler’s

complete works.

On the whole

it presents the music we

know as the first movement

of the Second Symphony, but

there are some notable

differences. The 1888

version contains two

passages in the first half

of the development section -

of nine bars and twenty bars

duration, respectively -

which Mahler

ultimately cut. (The second

of these contains a curious

allusion, almost surely

ironic, to the subject of Bach’s

"Little" G minor organ

fugue, BWV 578.) In

the process of pruning this

material he tightened the

movement's midpoint, which

involves a false reprise of

the opening fusillade for

strings. Nevertheless, in

different ways, both

versions manifest a

structural and expressive

conflict between two key

centers a semitone apart - E

and E flat - that Mahler

had in mind from the time of

his earliest sketches for

the piece. Indeed, such

halfstep juxtaposition is a

recurring motive throughout

"Totenfeier."

The earlier version also

contains two rather

redundant bars shortly

before the movements high

point that vvere later

deleted to good effect. As

regards instrumentation, the

1888 score calls for triple

winds, four horns, three

each of trumpets and

trombones, tuba, one harp,

one timpanist, and

percussion instruments

(triangle, cymbals, tam-tam,

bass drum), plus the usual

strings. In

the final version Mahler

expanded the forces to

include an extra flutist

(who, like the third

flutist, doubles piccolo),

two E flat clarinets, a

contrabassoon, two more

horns, plus an additional

trumpet, trombone, harp,

timpanist (with more drums),

and a higher-pitched gong.

Yet size is not the only

issue: although Mahler

was already a skilled

orchestrator in 1888, later

he became a much more

incisive one. His final

version of the movement

reveals an almost obsessive

capacity to wrest from the

orchestra precisely the

sound colors he sought.

·····

It was Mahler's "friendly

rival" Richard Strauss who

arranged for the first

public hearing of this music

The occasion was a partial

performance (three

movements) of Mahler’s

Second Symphony by the

Berlin Philharmonic in March

1895. Just before the

conclusion of the

"Totenfeier" movement, the

last of its E-to-E flat

semitone gestures produces a

striking major-to-minor

modal shift in the high

range of the trumpet choir.

Whether intentionally or

subconsciously, Strauss

chose just this motto for

the now-famous

“2001” opening of his own

next orchestral tone poem, Also

sprach Zarathustra

(Thus Spoke Zarathustra),

completed the follovving

year (1896).

The title comes from the

most famous (for some,

infamous) book by Nietzsche,

whose

alter ego Zarathustra

declares that God is dead

and preaches the necessity

of man's self-overcoming in

order to become an Übermensch

(best translated as

“Overman”) - the

self-determining

super-individualist who

climbs above and beyond the

comon herd. Zarathustra also

proclaims Nietzsche's

doctrine of the Eternal

Recurrence: “the

unconditional and infinitely

repeated circular course of

all things,” which

the philosopher also

characterized as "the

eternal hourglass of

existence... turned upside

down again and again, and

you with

it, speck of dust!" First

issued publicly in 1893

(after Nietzsche's mental

collapse in 1889), Also

sprach Zarathustra

had only just been taken up

by European artists and

intellectuals (Mahler, too,

was

intrigued by the book, and

set the poetry of

Zarathustra's midnight song

in his Third Symphony, also

composed in 1896).

The powerful

opening of Strauss's

30-minute tone poem is

generally understood to

represent the brilliant

sunrise marking the dawn of

Zarathustra's mission to

humanity. But in contrast to

some of his more explicitly

narrative tone poems.

Strauss here is not

attempting to set the book

to music: “Freely after

Nietzsche” was

his own

subtitle to the score.

Although he labels eight

sections of the music with

chapter headings from

Nietzsche (which

correlate with

the numbered tracks of this

recording), their sequence

bears no relation to the

books design. Nevertheless,

the composer's stated

intention “to convey in

music an idea of the

evolution of the human race

from its origin, through the

various phases of

development, religious as well

as scientific, up to

Nietzsche's idea of the

Overman" is partially

congruent with

the writer’s

agenda, as is Strauss's

description of the piece as

“symphonic optimism in fin-de-siècle

form, dedicated to the 20th

century.” And he surely

evokes something of the

Eternal Recurrence in the

half-step tonal conflict (cf.

"Totenfeier")

between the key centers of B

and C that returns

throughout the work,

even at its ending: the last

B cadence is quietly

disrupted by uncanny low

Cs in the basses, yielding

an open-endedness

that denies the traditional

tonal frame.

Stephen

E. Hefling

|

|

|