|

|

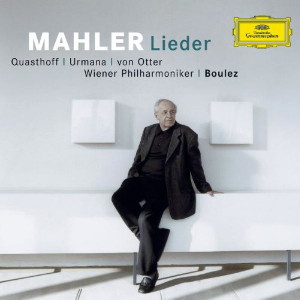

1 CD -

00289 477 5329 - (p) 2004

|

|

| GUSTAV MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

Lieder

eines fahrenden Gesellen

- Text: Gustav Mahler

|

16' 51" |

|

| 1.

Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht |

4' 12" |

|

| 2.

Ging heut morgen übers Feld |

3' 53" |

|

| 3.

Ich hab ein glühend Messer |

3' 09" |

|

| 4.

Die zwei blauen Augen |

5'

37" |

|

|

|

|

| 5

Lieder

- Text: Friedrich Rückert |

19' 36" |

|

| 3.

Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder |

1'

18" |

|

| 2.

Ich atmet einen linden Duft |

2'

37" |

|

| 1.

Liebst du um Schönheit |

2'

45" |

|

| 5.

Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen |

7'

02" |

|

| 4.

Um Mitternacht |

5'

54" |

|

|

|

|

Kindertotenlieder

- Text: Friedrich Rückert

|

24' 41" |

|

| 1.

Nun will die Sonn so hell aufgehn |

5'

44" |

|

| 2.

Nun seh ich wohl, warum so dunkle

Flammen |

4'

51" |

|

3.

Wenn dein Mütterlein

|

4'

57" |

|

| 4.

Oft denk ich, sie sind nur

ausgegangen |

3'

01" |

|

| 5.

In diesem Wetter, in diesem Braus |

6'

08" |

|

|

|

|

| Thomas Quasthoff,

bass-baritone (Gesellen) |

Wiener

Philharmoniker |

|

| Violeta Urmana,

soprano (5 Lieder) |

Pierre Boulez,

Conductor |

|

| Anne Sofie von

Otter, mezzo-soprano

(Kindertotenlieder)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Grosser

Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

(Austria) - giugno 2003 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive Producer |

|

Dr.

Marion Thiem / Ewald Markl |

|

|

Recording Producer |

|

Christian

Gansch |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer)

|

|

Rainer

Maillard |

|

|

Recording Engineer

|

|

Jürgen

Buldrin |

|

|

Editing |

|

Rainer

Maillard |

|

|

Recording

Coordinator |

|

Matthias

Spindler |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 00289 477 5329 - (1

CD) - durata 61' 28" - (p) 2004 -

DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Cover

Photo: © Harald Hoffmann

|

|

|

|

|

MAHLER:

LIEDER

“I have written a cycle

of songs, six of them so

far [...].

They are conceived as if a

travelling journeyman who

has been buffeted by fate

sets forth into the world

and goes wherever his

journey takes him."

This is the earliest mention

of Mahler’s

Lieder eines fahrenden

Gesellen and it comes

from a letter that the

composer wrote to one of his

oldest friends, Friedrich Löhr,

on 1 january 1885. The

ambiguity of Mahler’s

comment has meant that the

genesis of these songs has

been shrouded in obscurity,

not least because of the

lack of focus surrounding

the term “song” at this

time. Does it mean an

already complete setting of

a song text or merely a poem

that Mahler

intended to set to music at

some later date, a setting

that did not necessarily

exist at this time? The

surviving versions of these

songs for voice and piano or

orchestra all date from the

1890s. And yet it seems

fairly certain that the

piano versions of at least

some of these songs - the

exact number cannot be

determined - already existed

as a cycle and were written

at the end of 1884 and more

especially in 1885. But the

texts of only two of these

songs have survived from

this period: Die zwei blauen

Augen and Ich

hab' ein glühend

Messer, dated 15 and

19 December 1884

respectively. Described here

as “I”

and “II”,

they were to become the

fourth and third songs of

the complete set. In his

later letters, Mahler

always referred to the piano

version as a “piano

reduction”,

leading commentators to

assume that it was preceded

by an original version for

orchestra that is no longer

extant. But the term “piano

reduction” could also mean that Mahler

planned an orchestral

version as the definitive

form of the work, a

version that still

had to be written and which,

to judge by the surviving

sources, was not completed

until 1891-93.

Both the piano and

orchestral versions were

finally published after

repeated revisions in 1897.

If this is true, it is

conceivable that the first

song in the published cycle,

Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit

macht, with its

literal borrowings from Des

Knaben Wunderhorn, was

written around 1887, in

other words, after Mahler

had encountered this

Romantic icon of German folk

poetry in Leipzig. This

would render otiose any

further speculations as to

why Mahler

was able to write lines of

poetry mysteriously similar

to those from a source that

he is said not to have known

at this time.

The popularity of the Lieder

eines fahrenden Gesellen

is no doubt based above all

on the fact that they are

clearly part of the rich and

venerable tradition of

German song that includes

Schubert’s Die schöne

Müllerin

and Winterreise.

Like Schubert’s traveller,

who has similarly been "buffeted

by fate", Mahler’s

wayfarer suffers from

unrequited love, finding

himself in an unhappy

situation from which he

seeks in vain to escape.

Indeed, there are not only

textual links between the

cycles, but musical ones as

well: in addition to their

self-contained cyclical

structure, there is also a

walking rhythm, an

incessantly pulsing movement

in which the idea of

searching, with its hope of

fulfilment, is inextricably

bound up with flight as a

reaction to past sufferings.

In turn, the theme of

walking is linked to the

march that underpins all the

songs in the cycle - the

final song of farewell is

sung to the strains of a

funeral march.

It

may be helpful to attempt an

overview of the works that

were written at the same

time as the Rückert

Lieder:

Summer

1899: Revelge

(Wunderhorn)

1899/1900:

Fourth Symphony

(Wunderhorn)

Summer 1901:

Der Tambourg'sell

(Wunderhorn)

/ Four Songs (Rückert)

/ Kindertotenlieder

nos. 1, 3 and 4 (Rückert)

/ Fifth

Symphony, 1st

and 2nd

movements

Summer/autumn

1902:

Fifth

Symphony, 3rd,

4th, 5th

movements / Liebst

du um Schönheit

(Rückert)

1903/4:

Sixt Symphony

Summer 1904:

Kindertotenlieder

nos. 2 and

5

Summer

1904/5:

Seventh

Symphony

It is clear

from this that far from

completing one work before

moving on to the next, Mahler

worked on several at once,

the worlds that they inhabit

interlocking with one

another. The Wunderhorn

world of the last two Wunderhorn

songs and the Fourth

Symphony forms the basis of

an "instrumental

world" comprising the Fifth,

Sixth and Seventh

Symphonies, a world that not

only takes up and refashions

the earlier world (the Sixth

Symphony) but also provides

a transition to the

composer’s later works: Mahler

himself felt that his Ninth

Symphony was “most closely

comparable to the 4th”. And

his lieder seem to be links

that play a significant part

in the transformation of one

world into another. But

whereas the large-scale

settings of the Wunderhorn

poems have symphonic

aspirations, Mahler

turned for his Rückert

songs to an orchestral

language of chamberlike

transparency. Until now,

texts had been important to

him as raw materials imposed

on the music in order to

invest it with meaning, but

in Rückert’s

verse he encountered poetry

which thanks to its own

musicality conveys a sense

of musical meaning. Mahler

was now able to break free

from an illustrative or

psychologically

interpretative relationship

between words and music in

favour of music with a

latent linguistic character

that emerges from the fusion

between both these formative

levels.

In

Mahler’s own words, his Rückert

songs are among his most

personal works. The first, Blicke

mir nicht in die Lieder,

was "so

typical" of him that he

could have “written the words”

himself. In

Ich

atmet’ einen linden Duft

lay "the

muted emotion of happiness

that you feel in the

presence of someone you love

and of whom you are

completely certain without

the need for a single word

to pass between their two

souls" - it was in 1901 that

Mahler

was introduced to Alma

Schindler. And finally Ich

bin der Welt abend

gekommen: “That is my

very own self.”

On the strength of comments

made by his wife Alma,

commentators have repeatedly

claimed that the impetus

behind the Kindertotenlieder

was biographical in

character, namely, Mahler’s

disturbing youthful

experiences of rampant

infant mortality and, above

all, the notion of a link

with the death of his elder

daughter Maria

Anna in 1907, a link that

takes us into the realms of

mystic speculation and

supposes that, driven by

baleful presentiments about

the future, the composer

had, as it were, anticipated

her death and grieved over

it through his art. Such

speculations are baseless

and best avoided, for even

if personal experiences of

the tragic aspects of

existence undoubtedly found

their way into Mahler’s

music, they were all

transformed into an artistic

expression remote from pure

self-representation - for

all that Mahler

demonstrably sought this in

his art, in other words,

however much he aspired to

writing “programme music”.

To describe these five songs

as a cycle is questionable.

Although the individual

pieces contain balladic

elements, they can hardly be

said to tell a “story” - a

tale of children who, sent

out by their mother “in this

weather, in this tumult",

have perished in the storm.

We learn this only in the

final song, which as a

result comes closest to

providing a narrative and

which is cast in a

relatively discursive form -

this final song is almost

twice as long as its

predecessors. Why this

curious imbalance? This

impression is due in fact to

the "circuitous"

language of the final song,

in contrast to which the

four previous songs seem

like scenes of reflection

and painful contemplation on

irrevocable events. There is

also a suggestion here that

time is out of joint: first

we hear songs of grief and

mourning at an event that is

described in full only in

the final song. And this

shift clearly gives the

final song the character of

a finale: not only is it

extended by means of a

relatively lengthy

instrumental introduction

that includes dramatic

accents avoided until now

and a long coda-like final

section that brings the

turbulent scene to a

peaceful conclusion, but the

listener is bound to be

struck above all by its much

more elaborate orchestral

forces, which draw

additionally on piccolo,

contrabassoon, two extra

horns, tam-tam and celesta,

the symphonic impact of

which is in clear contrast

to the chamberlike tone of

the other four songs.

Mathias

Hansen

Translation:

Stewart

Spencer

|

|

|