|

|

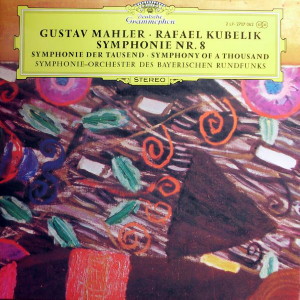

2 LP's

- 2707 062 - (p) 1971

|

|

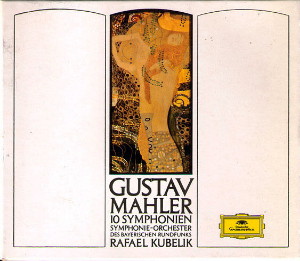

| 10 CD's

- 429 042-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie Nr. 8

Es-dur "Symphonie der Tausend"

|

|

73' 39" |

|

Long Playing 1 -

2530 240

|

|

|

|

| -

Teil I - Hymnus "Veni, creator

spiritus" |

21'

53" |

|

|

| -

Teil II (I) - Schluss-Szene aus

"Faust II" |

20' 39" |

|

|

Long Playing 2 -

2530 241

|

|

|

|

| -

Teil II (II) - Schluss-Szene aus

"Faust II" |

19' 39" |

|

|

| -

Teil II (III) - Schluss-Szene aus

"Faust II" |

11' 28" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Martina

Arroyo, Sopran I (Magna Peccatrix) |

Chöre

des Bayerischen, Norddeutschen und

Westdeutschen Rundfunks /

Josef Schmidhuver, Helmut Franz,

Herbert Schernus, Einstudierung

|

Erna Spoorenberg,

Sopran II (Mater gloriosa)

|

Knaben des

Regensburger Domchors /

Christoph Lickleder, Einstudierung

|

Edith Mathis,

Sopran III (Una poenitentium)

|

Frauenchor des

Münchener Motettenchors / Hans

Eudolf Zöbeley, Einstudierung

|

Julia Hamari,

Alt/Contralto I (Mulier

Samaritana)

|

Eberhard Kraus, Organ

|

Norma Procter,

Alt II (Maria Aegyptiaca)

|

|

Donald Grobe,

Tenor (Doctor Marianus)

|

Symphonie-Orchester

des Bayerischen Rundfunks |

Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau, Bariton

(Pater ecstaticus)

|

Rafael KUBELIK |

Franz Crass,

Bass (Pater profundus)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Kongreß-Saal

des Deutschen Museums, München

(Germania) - giugno 1970

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wilfried

Daenicke

|

|

|

Artistic

Supervision

|

|

Hans

Weber |

|

|

Recording

Engineer

|

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 2707 062 - (2 LP's) -

durata 32' 32" & 31' 07" - (p)

1971 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 429 042-2 - (10

CD's - 9°) - (c) 1989 - ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

Gustav Klimt

"Salome" (Detail)

|

|

|

|

|

Gustav Mahler's

Eighth Symphony is a work in

a class of

its own. It requires an

uncommonly large performing

apparatus - a huge orchestra

and organ, together with

a double mixed-voice choir,

a children’s choir and eight

soloists. In view of the

vast forces which pack the

platform this work has been

called the Symphony of a

Thousand, and the resources

it demands are certainly

more

extensive than those of any

of Mahler's other

symphonies. It is, however,

perhaps the easiest among

them to

understand. It poses

problems, but provides the

solution to them in musical

terms.

Mahler had good reason for

describing this work as a

symphony rather than, say, a

cantata for soli, chorus

and large orchestra. To him

the concept of the symphony

did not signify merely a

musical form which

existed as the product of a

process of development

spread over centuries; he

saw the symphony as being,

both in form and content,

the medium best suited to

the expression of what he

had to say - universal,

allembracing, and aspiring

towards the cosmic. He

considered the symphony an

ideal meeting place for

spiritual forces, and in

this instance he brought

together two

entirely dissimilar texts -

a medieval Latin hymn and

a dramatic scene from the

2nd part of Goethe's

“Faust’ - thus giving

expression to his conviction

that

his music would reveal

unmistakably the existence

of a

spiritual association of

ideas between the two texts.

The starting point of the

composition was the Latin

hymn “Veni, creator

spiritus!” Mahler had shown

from

the Third Symphony onwards

that to him the concept of

spiritual life and of God

was essentially one of love.

Consequently the first verse

of the hymn, with its appeal

to the Creator Spirit, was

followed by the equally

impassioned plea “Infunde

amorem cordibus!" (Pour

love into our hearts!). This

was love in Mahler's lofty

sense of the word - an

awakening power which

governs

and forms all things.

This hymn was originally

planned as the first

movement

of a symphony in which it

was to be followed by two

inner movements (a Scherzo

and an Adagio) and by a

Finale comprising a second

hymn corresponding to

the first, on the subject of

the birth of Eros. For a

long

time Mahler sought a

suitable text, a poem whose

words

corresponded to his ideas.

Once he had finally found

what he believed to be the

answer in Goethe, he had an

experience similar to that

which had given rise to the

Resurrection Chorale in the

Second Symphony: inspiration

came to him like a sudden

shaft of light, and the

essential structure of the

work which his imagination

had visualized was clear

before him. In the hymn love

has been invoked as the

creative and awakening

force;

here in the mystical closing

scene from “Faust” love reigns as the

mediating power which

progressively

raises, purifies, redeems

and transforms mankind. -

For

a real understanding of the

Eighth Symphony one

should not think in terms of

“Faust”, but should regard

its final scene as having

been transplanted from the

original context of the

poetic drama into a

different work

of art, of which it now

forms an organic part.

The starting point of all

Mahler's music was the lied.

The poems in the collection

“Des Knaben Wunderhorn"

provided the spark which

kindled his creative

imagination. The experience

which moved him so deeply

that it determined the

course of his creative work,

and of his life, originated

with the German folk song

and

Christian mysteries stylized

with a childlike simplicity.

Now in the Eighth Symphony,

written at the height of

his artistic powers and of

his career, he turned back

to

the world of ideas from

which he had originally set

out. He no longer pursued

the old ideas in their

naive,

childlike forms, but

fashioned them into mature

and immensely powerful

musical structures - the

Christian element in the

hymn, and that of German

folksong in association with

Goethe, whose artistry in

this anchorites’

scene represents a supreme

level of sublimated folk

poetry.

The use of this lengthy

scene from “Faust”

necessitated

the abandonment of Mahler's

original four-movement

plan. In actual fact,

however, it did survive,

although in

so disguised a form as to be

scarcely recognizable.

The composition of the scene

from “Faust” is based on a

concealed three-section

structure which may be

regarded as an Andante,

Scherzo and Finale. The hymn

corresponds to the

proportions and principles

of a sonata

form movement, with its main

theme and second, lyrical

theme clearly to the fore as

the principal elements

of the exposition. The

development section and

recapitulation are no less

easily recognizable.

If the composition of the

“Faust” scene is indeed a

disguised three-movement

structure, the layout of the

Symphony as a whole falls

into two main parts, as in

the

Third Symphony, where a

massive first part is

balanced by a second part

consisting of several

shorter

movements.

On the other hand the

thematic construction marks

a

definite change. While their

family relationship to

earlier themes is not to be

denied, the themes of the

Eighth

Symphony are calmer, more

direct, less nervous, less

wayward and excited.

Although not based on

folksong,

they often take on many of

the characteristics of folk

music.

The greater part of the

composition took place

during

the happy and productive

year 1906. Mahler worked at

that time in a fever of

creative enthusiasm, and

with the

sense of obeying a higher

command. The instrumentation

and final preparation of the

score were not, however,

completed until after Mahler

had left Vienna in

1907. The first performance

took place in September

1910, conducted by Mahler

himself in Munich.

Heinrich

Kralik

|

|