|

|

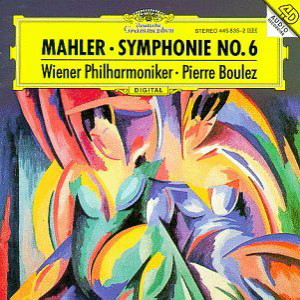

1 CD -

445 835-2 - (p) 1995

|

|

| GUSTAV MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie

No. 6 a-moll

|

79' 22" |

|

-

Allegro energico, ma non troppo

|

23' 06" |

|

| -

Scherzo. Wuchtig |

12' 19" |

|

| -

Andate |

14' 47" |

|

| -

Finale.

Allegro moderato - Allegro

energico |

29'

10" |

|

|

|

|

| Wiener

Philharmoniker |

|

| Pierre Boulez,

Conductor

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Grosser

Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

(Austria) - maggio 1994 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive Producer |

|

Roger

Wright

|

|

|

Associate

Producer |

|

Ewald

Markl |

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Werner

Mayer |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Rainer

Maillard |

|

|

Recording

Engineers |

|

Reinhild

Schmidt / Stephan Flock |

|

|

Editing |

|

Mark

Buecker |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 445 835-2 - (1 CD) -

durata 79' 22" - (p) 1995 - 4D DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Cover:

Alberto Magnelli, Lyric Explosion

no. 7, 1918 (Detail), Firenze,

Galleria d'Arte Moderna di Palazzo

Pitti.

|

|

|

|

|

In Mahler`s

Fifth Symphony, the journey taken by

thc imaginary hero had

seemed relatively

straightforward. leading, as

it does, from the opening

Funeral March to the joyful

Rondo-Finale: a case, quite

clearly, of per aspera

ad astra. In the Sixth

Symphony, by contrast, the

grim determination and

aggression of the opening

movement are merely

emphasized in the final

Allegro moderato which,

nevertheless, ends on a note

of defeat, the bitterness of

which is altogether

unalloyed. Such deleatism

and bitterness are all the

more surprising in that

there was nothing in

Mahler’s life at this time

that appears to justify such

black-hued

pessimism.

Unfortunately, very little

information is available on

the actual composition of

the Sixth Symphony since,

unlike his close friend and

confidante, Natalie Bauer-Lechner,

Alma Mahler was never a

particularly scrupulous

observer of her husband`s

creative life. By dint of

cross-checking, however, it

can be established that Mahler

- newly married and the

father of a little daughter

- arrived at Maiernigg

on 10 June

1903 and set to work without

delay. Alma recalls that he

returned from his Häuschen

(composing hut) one day and

told her that he had tried

to express her in a theme.

“Whether I’ve

succeeded, I don’t know; but

you'll

have to put tip with it."

The theme in question is one

of the few “positive”

gestures in the work: it is

the second subject of the

opening movement, an

ascending and descending

line in the major, energetic

and wilful, over which

Mahler has written the word

"Schwungvoll"

(with vigour) in the full

score. At the end of August,

when he returned to Vienna,

he had already completed the

two middle movements in

short score and had

undoubtedly sketched the

first.

At the beginning of the

following summer (1904),

Alma's

arrival in Maiernigg was

delayed by more than two

weeks since she had still

not recovered from the birth

of her second daughter, Anna

(known as "Gucki").

Throughout the whole of

June, heaven and earth

seemed to conspire to

prevent Mahler from

resuming work on the score.

The weather on the Wörthersee

was appalling during these

long days of solitude and

forced inactivity: the sky

was overcast, with frequent

storms and torrential rain.

The anxious feeling that so

often assailed him, namely,

that the wellspring

of his art had run dry,

continued to obsess him,

while he attempted to "pick

up the pieces of his inner

sell". By early July, the

weather improved, but

suddenly the heat became

unbearable. Incapable

of supporting it a moment

longer, Mahler rewarded

himself for the completion

of his song cycle Kindertotenlieder

and treated himself to a

lightning tour of the

Dolomites until such time as

Alma arrived. And it was

among the ragged peaks of

the Sextener Dolomites that

he finally found the inner

drive and inspiration that

allowed him to finish his

new symphony. By the end of

August, when he was

preparing to return to

Vienna, Mahler was able to

announce the completion of

the Sixth Symphony to his

friends Guido Adler and

Bruno Walter. However brief

the phrases, they were heavy

with evident pride.

To all appearances, the

summer of 1904

was the most peaceful of all

the summers that he spent in

Carinthia. How, then, can we

explain the fact that it was

at precisely this time that

he wrote the most tragic of

all his works? According to

Alma he later recognized in

the three hammer blows of

the final movement a

premonition of the three

blows of fate that were to

fall on him in 1907: the

death of his elder daughter,

the diagnosis of a

potentially dangerous heart

condition and his departure

from Vienna.

In

comparison to that of its

predecessors, the four-movement

form of the Sixth Symphony

might appear to represent a

return to Classical norms.

The Fifda, after all, had

been in five movements, the

Third in six. On closer

inspection, however, it

becomes clear that the new

work surpasses all that Mahler

had previously written in

terms of its boldness and

the dimensions of its final

movement. In May 1906,

during the rehearsals

preceding the world première

at Essen, Mahler had doubts

concerning the order of the

two middle movements.

Initially, the order was

Allegro, Scherzo, Andante

and Finale. It

was, however, at Essen that

Mahler probably allowed

himself to be influenced by

a number of his friends, who

pointed out the striking

similarity between the

opening of the Scherzo and

that of the initial Allegro.

A few months later, in

January 1907,

he decided to revert to the

original order. These

hesitations and changes of

mind on numerous points of

detail and even on a matter

as important as the order of

the movements are confirmed

by Mahler`s

contemporaries. As was so

often the case, Mahler felt,

while writing the Sixth

Symphony, that he was the

instrument of a power

greater than himself. On

this occasion, however, that

power was mysterious, tragic

and implacable, plunging him

into a state of

insurmountable anguish. What

is this power with which Mahler’s

symphonic heroes are forced

to contend and to which they

often succumb, as is the

case at the end ofthe Sixth

Symphony? It

is a struggle that Mahler

himself had to face, as he

made clear in a striking

remark when, following the

final rehearsal, one of his

friends asked him: “But how

can someone who is so good

express so much cruelty and

harshness in his work?” To

which he replied: “They are

the cruelties I’ve suffered

and the pains I’ve felt!”

Every work of art worthy of

the name must satisfy two

contradictory demands: unity

and diversity. In his Sixth

Symphony, Mahler meets both

these requirements by

adopting solutions as

magisterial as they are

novel. Never before had he

taken such pains to create a

network of cyclical

relationships between the

different movements and to

draw on what was in fact a

very limited reservoir of

thematic

cells in order to

produce an infinite number

of themes and motifs. From

the outset Mahler defines

the work’s negative,

pessimistic character with a

harmonic leitmotif which

reverses the traditional

order of modes, prefacing

the minor with a major mode.

This order is repeated on

numerous occasions, almost

always accompanied by

another, rhythmic,

leitmotif.

A model of Classical

balance, the opening Allegro

energico is cast in

first-movement sonata form,

with an exposition involving

the traditional repeat. Here

Mahler takes his definitive

leave of the past, of Des

Knaben Wunderhorn,

which is replaced by a world

that is cruel and almost

wilfully unappealing:

angular, sometimes even

unattractive themes

characterized by wide

intervals, ostinato rhythms

and a tense, strained and

anguished atmosphere. The

hero of the symphony departs

for war to an energetic

march rhythm articulated on

a percussion instrument

borrowed from the world of

military music - the side

drum. A double exposition of

the principal subject is

followed by a transitional

episode on the woodwind, a

bridge passage in long

note-values in the form of a

chorale divested of its

normal contents and imbued,

instead, with a sort of

hollow formalism and bizarre

harmonies. Unlike the songs

of triumph and faith that

play an essential role in

Bruckner`s symphonies, this

is a “negative” chorale and,

as such, one of the

symphony`s most striking

innovations. As Theodor

Adorno has shown, it leads

nowhere and prepares for

nothing - certainly not for the

"Alma" theme, which enters

in a moment as a veritable

intrusion.

This second thematic element

is one of a large family of

ascending (and, hence,

optimistic) motifs that had

earlier produced many of

Mahler`s themes. But it

seems to embody not so much

the reality as the idea that

Mahler had (or wanted to

have) of Alma: it is neither

the charm nor the beauty of

his young wife that he

evokes here but a wilful,

not to say forced, optimism.

A section of the development

deserves particular

attention, the moment of

idyllic calm in which the

woodwind and horn exchange

fragments and variants of

Alma’s theme against a

background of violin

tremolandi. Here for the

first time we hear the sound

of cowbells, a symbol of

contented isolation far

removed from the turmoil of

human existence. The

movement ends in A major,

but it is a tonality that

sounds bombastic rather than

genuinely triumphant, as if

the "hero" wanted to

convince himself that he had

triumphed, without really

believing in his own

victory.

For the Scherzo, marked

“Wuchtig” (weighty), Alma

provided a “key” that could

scarcely be less convincing:

it represented, she claimed,

"the arrliythmic games of

the two little children,

tottering

in zigzags over the

sand” in the garden at Maiernigg. But

in 1903, the date when these

two middle movements were

written, Anna had not yet

been born and Putzi was no

more than eight or nine

months old. One is tempted,

rather, to hear in this

Scherzo a neo-medieval Dance

of Death of the kind

inaugurated by the “Funeral

March in Callot”s Manner” of

the First Symphony. I say

“dance”, but it must be

admitted that this eerie

Scherzo never really dances,

or, rather, it dances with a

limp, since the triple

rhythm is incessantly

contradicted by accents

placed on the weak beat in

each bar. The general

atmosphere is gloomy and

grimacing, a mood to which

the orchestration

contributes with its use of

instruments, such as the piccolo,

E flat clarinet and

xylophone, notable for their

shrill sonorities. With its

changes of time signature,

rhythmic instability and

formal and old-fashioned

counterpoint, the Trio is no

less disquieting. Grotesque

marionettes dressed in fusty

clothes seem to perform an

ungainly dance with an

almost pathetic clumsiness.

It is left to the Andante moderato

to introduce a note of

contrast into the symphony`s

cruel and hostile world.

Indeed, its expansive

lyricism makes it Mahler`s

only authentic symphonic

Andante, with the exception

of that of the Fourth. Its

opening theme, often accused

of “banality” by Mahler`s

contemporaries, was analysed

in detail by Arnold

Schoenberg, who underlined

its asymmetries and ellipses

and, above all, the fact

that it is never restated in

its original form. Melodically

speaking, it still belongs

to the world of the Kindertotenlieder,

but without the atmosphere

of mourning. Two contrastive

episodes follow, the first

on the strings, the second

in the minor on the winds,

but they are soon combined

and even confused. Triplets

that turn back on

themselves, trilling

birdsong and cowbells evoke

the blissful calm of nature

from which Mahler drew the

greater part of his creative

energies.

With the exception of Part II of

the Eighth Symphony, where

the form is prescribed by

the text (the final scene

from Goethe`s Faust).

the Sixth’s epic Finale is

the longest of Mahlers

movements. An immense

musical "novel" whose

elements, as always, are in

a state of perpetual

evolution by virtue of a

principle defined by Adorno

as "the irreversibility

of time", it is structured

around a fourfold repetition

of its slow introduction.

With its opening bars the

blackest of nights envelops

us, a chaos suggestive of

the end of the world.

Fragments of themes shoot up

through the darkness, only

to fall away again. After a

great initial "cry" that

rises to the violins`

highest register before

plunging down to the cellos’

lowest notes,

we hear. in succession, the

symphony’s double leitmotif,

harmonic and rhythmic; an

ascending octave-motif, on

the tuba, recalling the

opening movemcnt’s initial

theme, followed by an

arpeggiated motif borrowed

from the Scherzo and,

finally, an anticipation of

the second theme, which is

the only optimistic element

in this final movement. But

the most striking element in

this introduction is

undoubtedly the episode

marked "schwer" (heavy) on

the winds. another

chorale-like passage but

even more paradoxical and

negative than that of the

opening movement.

The principal theme of the

Allegro moderato is made up

of all the elements that

have been previously

introduced. In the first

reprise of the introduction,

the initial "cry" is

inverted and differently

harmonized, in which form it

introduces the development

section, a section that

defies all attempts at

succinct analysis. Two

hammer blows separate the

main sections of this epic

struggle. In the

recapitulation, which is

considerably foreshortcned,

the order of the two

principal thematic elements

is reversed, the major

preceding the minor as in

the symphony`s principal

leitmotif. A final variant

of the opening "cry",

accompanied in its final

bars by both the major-minor

and the obsessive, rhythmic

leitmotifs, heralds the

final catastrophe. No other

piece of music approaches

this coda for its sense of

devastation and desolation.

A slowed-down version of the

ascending-octave motif is

passed to and fro among the

orchestra’s lowest

instruments in a sort of

sombre threnody

or stricken dirge. The

movement ends with a final

reprise of the octave motif,

this time on the lowest

strings. It is brutally

interrupted by a fortissimo

minor chord (not preceded on

this occasion by the major)

that is underpinned by the

rhythmic leitmotif as it

gradually dies away. All

that remains is despair, the

dark night of the soul and

the sense of defeat summed

up by this haunting rhythm.

Is

there any need to speculate

further on the meaning of an

ending described by Adorno

as "all's

ill that ends ill"? For my

own part, I think that all

human beings pass through

such moments of absolute

despair and that Mahler is

just as much himself here as

he is in the triumphant

tones of the Eighth

Symphony. As a creative

artist he was bound to

explore the dark and

desolate landscapes of the

Sixth before discovering, in

his subsequent works, other

pathways leading to other

horizons. The blackness of

the Sixth Symphony was an

indispensable stage in his

evolution that would lead

him to the radiant optimism

of the Eighth and, later and

entirely naturally, to the "azure

horizons" and luminous

vistas which, at the end of

Das Lied von der Erde,

open on to eternity.

Henry-Louis

de La Grange

|

|

|