|

|

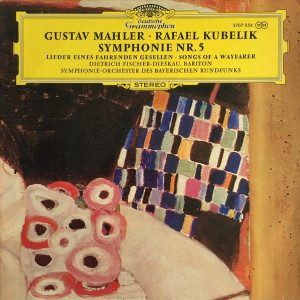

2 LP's

- 2707 056 - (p) 1971

|

|

| 10 CD's

- 429 042-2 - (c) 1989 |

|

| GUSTAV

MAHLER (1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Long Playing 1 -

2530 189

|

|

42' 50" |

|

Symphonie Nr. 5

cis-moll

|

|

66' 03" |

|

| Erster Teil |

|

|

|

| -

1. Trauermarsch. In gemessenem

Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt |

11' 35" |

|

|

| - 2. Stürmisch

bewegt, mit grösster Vehemenz |

13' 52" |

|

|

| Zweiter Teil |

|

|

|

| - 3. Scherzo.

Kräftig, nicht zu schnell |

17' 23" |

|

|

Long Playing 2 -

2530 190

|

|

39' 21" |

|

| Dritter Teil |

|

|

|

-

4. Adagietto. Sehr langsam -

attacca:

|

9' 44" |

|

|

| -

5. Rondo-Finale. Allegro |

13' 29" |

|

|

| Lieder

eines fahrenden Gesellen |

|

16' 08"

|

|

| -

1. Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht |

3' 51" |

|

|

| -

2. Ging heut' morgens übers Feld |

3' 59" |

|

|

| -

3. Ich hab' ein glühend Messer |

3' 10" |

|

|

| -

4. Die zwei blauen Augen |

5' 08" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau, Baritone |

|

| Symphonie-Orchester

des Bayerischen Rundfunks |

|

Rafael KUBELIK

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Herkules-Saal,

München (Germania):

- gennaio 1971 (Symphony)

- dicembre 1968 (Lieder)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Wilfried

Daenicke |

|

|

Recording

Producer

|

|

Hans

Weber (Symphonie), Rainer Brock

(Lieder: 1,2,4), Wolfgang Lohse

(Lieder: 3)

|

|

|

Balance

Engineer

|

|

Heinz

Wildhagen |

|

|

Prima Edizione

LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 2707 056 - (2 LP's) -

durata 42' 50" & 39' 21" - (p)

1971 - Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione

CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 429 042-2 - (10

CD's - 6°) - (c) 1989 - ADD

|

|

|

Note |

|

Illustration:

Gustav Klimt "Salome"

(Ausschnitt) |

|

|

|

|

The beginning

of the composition of his

Fifth Symphony marked the

opening of a new chapter of

Mahler's work in the

symphonic field.

Nevertheless in every

respect - intellectual,

musical, architectonic,

harmonic and textural - new

elements here came to the

forte. These elements are of

great importance to the

Fifth, Sixth and Seventh

Symphonies, which together

form a sub-group within

Mahler's symphonic uvre.

The Fourth was completed in

the summer of 1900, and the

Fifth was composed during

the following two years.

Nothing is known of any

outward experiences or inner

transformations during that

period which could account

for the new mode of

expression. There was,

therefore, no outward

struggle which could have

threatened the composer's

career and shattered his

peace of mind, so the

stylistic change in Mahler's

compositions must have been

entirely inward in its

origins, resulting from a

change of personality.

Mahler's music provides us

with the only indication

that his inner life

underwent a change at that

time. Prior to that the

source of his inspiration

had been a mystical concept

of life and of nature. His

music had been directed, as

it were, towards the

solution of the world's

problems. The mystery of the

giving of life to the

inanimate by spiritual means

had been the subject of his

musical aspirations. Now,

however, that theme was

exhausted. He had pursued it

into the most lofty, purest

spjeres until, freed from

all pathetic and dynamic

elements, it had dissolved

in fairy tales, symbols, and

the simple beliefs of

childhood. The composer now

had to make a new beginning,

to seek out a new way. There

was only one road to take;

it led from the world of

fairy tales into reality,

from dreams to a conscious

confrontation with the

world.

This is what the next trio

of symphonies, the Fifth,

Sixth and Seventh, have to

offer: they are no longer

mystic reveries, but music

directed towards the real

world, instrumental

symphonies which have their

origins in impulses of

absolute music, rather than

works set in motion by

lirical or poetic concepts.

The Fifth Symphony is

unfolded on a very large

scale. The idea of division

into several major sections,

which Mahler introduced in

his Third Symphony, is again

evident here. On this

occasion there are three

such sections, and it can

scarcely be doubted that the

second of these, a grandiose

Scherzo which one might

almost describe as larger

than life size, is the most

important movement of all.

This Scherzo is no dance or

character piece in the older

sense, but an expression of

inflexible strenght and of

an exuberant urge to take

action. It is not emotional

or spiritual experiences

which hold the musical

events of this movement

together; what creates an

arresting effect here might

be described as a vigorous

play of abstract musical

forces.

The two sections which flank

this central Scherzo, each

of them comprising two

movements, are to be

understood in relation to

the Scherzo. The first

section begins with a

Funeral March in C sharp

minor, followed by a warlike

Allegro in A minor. The

heading "Funeral March" is

the only quasi-programmatic

indication in the score. Who

is being carried to the

grave here? Neither a hero

nor a specific personality.

But perhaps the reference is

to part of Mahler's own

past, from which he severed

himself in this solemn and

demonstrative manner. The A

minor Allegro which follows

might then be said to mark

the beginning of a fresh

life, a new phase of

intensified activity which

can produce results only if

every ounce of effort is

expended. The forceful,

often aggressive character

of this music shows clearly

that a grim conflict is to

take place. However, by the

time the tumult subsides,

and the divergent strands of

the orchestral texture come

together in music suggesting

a chorale, the positive

out-come of the conflict is

no longer in doubt.

After the Scherzo, which has

already been described as a

play of musical forces, the

third section of the

Symphony opens with a tender

Adagietto, whose aesthetic

purpose os, perhaps, to

re-introduce feeling and

contemplation after the

previous complete domination

of force and willpower. This

piece is concise in form and

is orchestrated with extreme

delicacy, only harp and

strings being used. It is

almost miraculous that this

Adagietto, with its

delicacy, its modest scale

and tonal restraint, is not

stifled by the colossal

movements surrounding it.

The fifth movement follows

without a break. It may be

said that this movement

exploits in a practical

manner what the Scherzo

presented in abtract; it

makes use of such concrete

musical materials as themes,

figures, and shapes which

are no longer pure spirit

but also have bodily

substance. The gaiety with

which the principal theme is

introduced, after various

other motives have been

tried out and discarded, is

reminiscent of the humour of

Joseph Haydn, and indeed the

principal theme itself has a

somewhat Haydnesque cut.

Only at the beginning is it

marked by simplicity,

however. This movement, full

of exuberant joie de vivre,

becomes a thing of extremely

complex patterns. Never

before had Mahler made use

of contrapuntal technique

with such zeal and mastery.

It is not always easy to

analyze the formal structure

of this Rondo Finale. No

effort is needed, through,

to enjoy the effect created

by this immensely lively

musical expression of joy.

Heinrich

Kralik

|

|