|

|

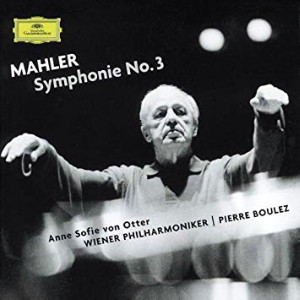

2 CD's

- 474 038-2 - (p) 2002

|

|

| GUSTAV MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

No. 3 |

80'

36" |

|

| Erste Abtleitung |

|

|

| -

Kräftig. Entschieden |

33'

34" |

|

| Zweite

Abtleitung |

|

|

| -

Tempo di Menuetto. Sehr mäßig |

9'

27" |

|

| -

Comodo. Scherzando. Ohne Hast |

16'

38" |

|

|

|

|

| -

Sehr langsam. Misterioso. Durchaus ppp

"O Mensch! Gib acht!" (text:

Friedrich Nietzsche, "Also

sprach Zarathustra") |

9'

17" |

|

| -

Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck

"Bimm bamm! Es sungen drei Engel"

(text: "Des Knaben

Wunderhorn") |

4'

05" |

|

| -

Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden |

22'

22" |

|

|

|

|

Anne Sofie von Otter,

Mezzo-Soprano

|

Frauenchor des

Wiener Singverein / Johannes Prinz,

Chorus Master |

|

|

Wiener Sängerknaben

/ Gerald Wirth, Chorus Master |

|

|

Wiener

Philharmoniker |

|

|

(Werner Hink, violino

solo / Hans Peter Schuh, posthorn

solo / Ian Bousfield, trombone

solo) |

|

|

Pierre Boulez,

Conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Grosser

Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

(Austria) - febbraio 2001 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive Producer |

|

Dr.

Marion Thiem |

|

|

Associate Producer |

|

Ewald

Markl |

|

|

Recording Producer |

|

Christian

Gansch |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer)

|

|

Rainer

Maillard |

|

|

Editing |

|

Rainer

Maillard |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Wolf-Dieter

Karwatky |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 474 038-2 - (2 CD's)

- durata 59' 39" | 35' 44" - (p)

2002 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Cover

Photo: Philippe Gontier

|

|

|

|

|

The composer

who writes "a major work,

literally reflecting the

whole world, is himself only

an instrument being played

by the whole universe". This

oft-quoted phrase could have

been uttered only by Mahler,

and then only in a rare

moment of exaltation such as

that which inspired one of

his most imposing, ambitious

and vast creations, the

Third Symphony.

During the early summer of 1895

he returned to Steinbach on

the Attersee, where he had

composed the Second Symphony

and there wrote the minuet

to which he later gave the

name Blumenstück,

inspired by the

flower-strewn meadow

surrounding the hut. Even at

this early stage he already

had a plan of the whole

work, one of the most

ambitious designs ever

conceived for a symphony.

Starting out from inert

matter - rocks and inanimate

Nature - he could already

glimpse how the vast epic

would proceed, one by one,

through the stages of

evolution: to flowers,

animals and mankind itself

before ascending to

universal love, which he

imagined as a supremely

transcendental force.

This programme passed

through several different

versions, but it must be

stressed that Mahler

finalized it before he

embarked on the score. At no

point did he ever disown it,

even though he later forbade

the publication of any

explanatory text when his

works were performed. The

opening movement was

initially called "The

Arrival of Summer" or "Pan's

Awakening" and, later, "Procession

of Bacchus". It appears that

the initial Allegro

(actually composed the

following year, 1896), was

not yet preceded in his

scheme by the long

introduction in D minor,

music that Mahler was later

to say could have been

subheaded "What

the Mountains Tell Me." The

other movements already bore

their definitive titles:

2. "What

the Flowers of the Meadow

Tell Me"

3. "What

the Animals of the Forest

Tell Me"

4. "What

the Night Tells Me" (later

changed to "What

Mankind Tells Me")

5. "What the Cuckoo Tells

Me" (replaced by "Morgenglocken"

[Morning Bells] and, later,

by "What

the Angels Tell Me")

6. "What

Love Tells Me"

In Mahler's original plan,

there was a seventh,

movement, "What

the Child Tells Me": the

song Das himmlische

Leben, written three

years earlier and

subsequently taken over into

the Fourth Symphony.

After the minuet, the next

four movements were written

during this first summer of

1895. For the opening

movement, which was to be

the longest of the six,

Mahler merely noted down a

few musical sketches,

deferring composition itself

until the following summer.

When he returned to

Steinbach on 11

June 1896

with the intention of

resuming work, it proved, as

always, far more difficult

to reimmerse himself in the

score than he had envisaged,

the transition from his life

as a performing artist to

that of a creative musician

invariably causing him

considerable anguish. Yet in

less than a month, by 11 July

1896.

the first movement was

completed in short score.

For the present, the

introduction was still

conceived as a separate

movement, but it was

gradually assuming a new

significance: no longer

would it depict soulless,

lifeless Nature imprisoned

beneath the winter ice, but

instead the stifling heat of

summer, when "not

a breath stirs, all life is

suspended, and the

sun-drenched air trembles

and vibrates. At intervals

there come the moans [...]

of captive life struggling

for release from the

clutches of lifeless, rigid

Nature". Alive to the "mystery

of Nature",

Mahler believed that music

alone could "capture its

essence". A letter written

at the time finds him both

lucid and elated: "My

symphony will be something

the world has never heard

before.

In it Nature herself

acquires a voice and tells

secrets so profound that

they are perhaps glimpsed

only in dreams!"

In an attempt to justify the

extraordinary length of its

opening movement, Mahler

divided the symphony into

two Abteilungen, or

sections: the first

comprises the initial

Allegro, while the second

includes the remaining five

movements. Originally he had

intended to impose a sense

of thematic unity on all

six, and though this plan

was not finally adopted, he

did use several motifs from

the opening Allegro in the

fourth and sixth movements.

The first performance of the

Third Symphony, in Berlin on

9 March 1897 was

incomplete, comprising only

the second, third and sixth

movements.

The booing nearly drowned

the applause; and the

critics of the German

capital surpassed

themselves, writing of the

“tragicomedy" of a composer

lacking both imagination and

talent, and of a work made

up of "banalities" and “a

thousand reminiscences". But

they were particularly

exasperated by the final

movement, with its

"religious and mystic airs",

and dismissed its main theme

as "a formless tapeworm".

Five years later, however,

in June

1902, the symphony was

performed complete for the

first time at Krefeld in the

Rhineland, and on this

occasion it was the

contemplative power of the

final Adagio that conquered

even the most wilfully

hostile listeners. In

the view of one critic, it

was "the most beautiful slow

movement since Beethoven".

The evenings triumph opened

the doors to a new era in Mahler’s

life and career.

1. Kräftig.

Entschieden

(Powerfully. Decisively).

The first movement of the

Third Symphony is still cast

in the sonata form that had

obsessed Romantic composers

anxious to maintain the

Beethovenian ideal - with

the difference that there

are two expositions instead

of one.

Stated fortissimo on

eight horns in unison, the

initial march-theme serves

as a gateway to the rest of

the work and plays an

essential role throughout

the whole of this opening

movement. It, too, refers to

the past, in this case to

the final movement of

Brahms's First Symphony.

As we have already seen, the

most striking feature of

this opening movement is the

stylistic contrast, not to

say disparity, between the

two main subject groups. The

first subject is music of

darkness and chaos: noble,

powerful and grandiose in

the most Romantic and

traditional sense of the

term.

Embodying motionless,

imprisoned Nature, it takes

its place in the grand

symphonic tradition

established by Beethoven and

continued by Bruckner. The

second subject, evoking the

Bacchic procession, is

distinguished by its

blatantly populist

character; it belongs to the

“lower” world of brass bands

and military music whose

cheerful simplicity, candour

and even naivety for Mahler

invariably concealed a

musical and intellectual

mechanism which shaped and

structured the musical

discourse with conscious,

unrelenting rigour.

2. Tempo di Menuetto.

Sehr mässig

(Very moderate). The

flowers of the meadow at

Steinbach inspired Mahler

to write a minuet whose

tribute to the past has

nothing ironic about it but

which dances with an

exquisite grace. Two

episodes alternate in

symmetrical fashion.

Although they are identical

in tempo, the second seems

faster by virtue of its

shorter note-values.

3. Comodo. Scherzando.

Ohne Hast

(Unhurriedly). Although

binary rather than ternary,

this movement is the

symphony's scherzo. With the

exception of the Trio, all

the thematic material is

borrowed from the song Ablösung

im Sommer (Relief of

the Summer Guard), in which

the spring cuckoo is

replaced by the summer

nightingale. The songs

melodic material is

repeatedly transformed and

developed, with contrast

being provided by one of the

most magical moments in any

of Mahler's

works, namely, the passage

for solo posthorn, which is

played "in

the distance", i.e.,

off-stage. Mahler’s

contemporaries were

scandalized by the alleged "banality"

of this long solo, but it

delights us today as a

moment of unalloyed poetry.

No less notable are the

great wave of impassioned

anguish and "cry

of terror" that ring out

towards the end of the

movement in a powerful brass

fanfare. It is in this way,

Mahler suggests, that the

animals react to mankind's

intrusion upon their world.

4. Sehr langsam

(Very slow). Misterioso. The

role of |Nietzsche's "Drunken

Song" or “Midnight Song”

differs little from that of

Urlicht in the Second

Symphony. In the middle of

the night, at the darkest

and deepest hour, Life makes

Zarathustra feel ashamed of

his anguish and doubts and

bids him meditate between

the twelve strokes of

midnight on the secret of

the worlds, their profound

pain and even more

mysterious joy, and on the

ardour of that joy which,

far from bewailing its

ephemeral fragility, yearns

for eternity. In the course

of this meditation, man

discovers the way of truth

and accedes to a higher form

of existence in the

childlike purity of the

fifth movement and the

mystic contemplation of the

sixth. The form here is very

free, with deliberately

indistinct rhythms and

“weak” harmonic progressions

suggesting night's

immobility. Everything

revolves around contrasts of

timbre and register.

5. Lustig im Tempo und

keck im Ausdruck (Cheerful

in tempo and cheeky in

expression).

The text of "Es

sungen drei Engel" is taken

from Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

For this briefest of the

work's six movements, Mahler

paradoxically calls on its

most elaborate forces, with

double chorus of women and

children in addition to the

female soloist of the

previous movement, and

entrusts a children's choir

with the task of imitating

morning bells. Yet the

radiant luminosity of these

fresh-sounding voices gives

the scene the bright-toned

colours that Mahler desired.

6. Langsam, Ruhevoll.

Empfurnen

(Slow. Calm. Deeply felt). A

glance at the opening pages

of the score of this vast

slow movement might suggest

a simple exercise in

polyphonic writing, but no

listener can remain

insensible to its serenity

and grandeur, to its

powerful assertion of faith,

to its hypnotic

motionlessness that is

mystical and contemplative

rather than meditative. Here

we find Mahler

donning the mantle of the

legitimate heir of the great

Baroque and Classical

traditions, a heritage

recognizable by its subtle

art of variation that

untiringly transforms

thematic elements which,

always familiar, are always

different. As usual, there

are two alternating subject

groups, one in the major,

the other in the minor. But

the rare moments when

anxiety makes itself felt

merely serve to underline

the tranquil certainty of

the movement as a whole.

This apotheosis is

undoubtedly the most

authentically optimistic of

any by a composer so often

described as “morbid” and

obsessed with anguish and

death. All questions find an

answer here, all anguish is

assuaged. With this hymn of

praise to the Creator of the

World, conceived as the

supreme force of Love,

Mahler took the final step

on the road to Eternal Light.

Henry-Louis

de La Grange

|

|

|