|

|

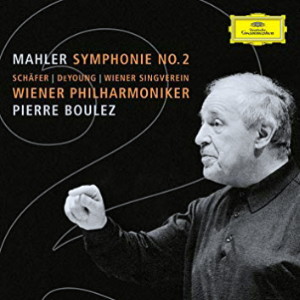

1 CD -

00289 477 6004 - (p) 2006

|

|

| GUSTAV MAHLER

(1860-1911) |

|

|

|

|

|

Symphonie

No. 2 "Auferstehungs-Symphonie"

|

80'

36" |

|

| -

Allegro maestoso. Mit durchaus

ernstem und feierlichem Ausdruck |

20'

55" |

|

| -

Andante moderato. Sehr gemächlich |

9'

17" |

|

| -

In ruhig fliessender Bewegung |

9'

27" |

|

-

"Urlicht" (from Des Knaben

Wunderhorn) Sehr feierlich,

aber schlicht *

|

5' 36" |

|

| -

Im Tempo des Scherzo. Wild

herausfahrend - "Aufesteh'n" (text:

Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock &

Gustav Mahler) |

35' 21" |

|

|

|

|

Christine Schäfer,

Soprano

|

Wiener Singverein

/ Johannes Prinz, Chorus Master |

|

Michelle DeYoung,

Mezzo-Soprano *

|

Rainer Jeuschnig,

Organ |

|

|

Wiener

Philharmoniker |

|

|

Pierre Boulez,

Conductor |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Grosser

Saal, Musikverein, Vienna

(Austria) - maggio/giugno 2005 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Executive Producer |

|

Marion

Thiem |

|

|

Associate Producer |

|

Ewald

Markl |

|

|

Recording Producer |

|

Christian

Gansch |

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer)

|

|

Rainer

Maillard |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Wolf-Dieter

Karwatky |

|

|

Recording

Coordinator |

|

Matthias

Spindler |

|

|

Editing |

|

Rainer

Maillard |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 00289 477 6004 - (1

CD) - durata 80' 36" - (p) 2006 -

DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

Cover

Photo: © Harald Hoffmann

|

|

|

|

|

The ink was

barely dry on the score of

his First Symphony in 1888

when Mahler

began to toy with the idea

of a new large symphonic

work in C minor. The opening

movement was soon completed

and named Todtenfeier

(Funeral Ceremony), but it

then languished among his

papers until 1891, the year

in which he left the

Budapest Opera to become

conductor in Hamburg. There

he attracted the attention

of the great conductor Hans

von Bülow,

well known as a champion of

new music. When Mahler

played him Todtenfeier

on the piano, however Bülow

covered his ears and

groaned: "If what I have

heard is music, I

understand nothing about

music. [...]

Compared with this, Tristan

is a Haydn symphony."

Mahler’s

creative urge survived the

master’s cruel words, but

the Hamburg Opera now

consumed most of his time

and energy, and it was not

until the summer of 1893,

spent near Salzburg, that he

returned to the Symphony in

C minor. He soon completed

the Andante he had sketched

five years earlier.

Immediately afterwards there

occurred one of the

strangest episodes in his

entire creative life:

simultaneously and on

identical musical material,

he composed the song Des

Antonius von Padua

Fischpredigt and the

new symphony's Scherzo. Work

was progressing at a

dizzying speed, but when the

end of the summer came and,

with it, the time for his

return to Hamburg, Mahler

had not yet made any

sketches for a finale,

though he had composed the Wunderhorn-Lied

entitled Urlicht,

which would serve as its

introduction. What he still

lacked was a text for the

powerful choral ending he

had in mind, something

comparable to the finale of

Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.

In February 1894, Bülow

died and Mahler

attended his memorial

service in Hamburg. During

the ceremony he experienced

a revelation when ”the

choir, in the organ-loft,

sang Klopstock's

Resurrection Chorale.

It was like a flash of

lightning, and everything

became plain and clear in my

mind!" The initial sketches

were noted down immediately

on his return home from the

service, and the actual

composition of the finale

was completed within the

space of three weeks the

following summer. Mahler

had added a number of lines

to Klopstock's

ode, not only amplifying the

poet’s ideas but also

altering their message.

As was his custom at this

early stage of his career,

Mahler drew up several,

essentially similar

programmes for the symphony.

In the first movement, the

”hero" is laid in earth

after a long struggle with

"life and destiny". Casting

a backward glance at his

life, he recalls a moment of

happiness (the Andante),

then reflects on the cruel

turmoil of human existence,

in a "spirit of disbelief

and negation" (the Scherzo).

"He despairs of himself and

of God. [...] Utter disgust

for every form of existence

and evolution seizes him in

its iron grip, tormenting

him until he utters a cry of

despair."

A redeeming "Urlicht"

(Primeval Light) then shines

from afar. "Stirring words

of simple faith" in the

fourth movement sound in the

hero's ear, bringing a

glimmer of hope.

Nevertheless, a long

distance still has to be

travelled before the final

apotheosis. The finale

begins with a vision of

terror: "The horror of the

day of days has come upon

us. The earth trembles, the

graves burst open, the dead

arise and march forth in

endless procession. The

great and the small of this

earth, the kings and the

beggars, the just and the

godless, all press forward.

The cry for mercy and

forgiveness sounds fearful

in our ears. The wailing

becomes gradually more

terrible. Our senses desert

us; all consciousness dies

as the Eternal Judge

approaches. The Last Trump

sounds; the trumpets of the

Apocalypse ring out. In the

eerie silence that follows,

we can just barely make out

a distant nightingale, a

last tremulous echo of

earthly life. The gentle

sound of a chorus of saints

and heavenly hosts is then

heard: 'Rise again, yes,

rise again thou wilt!' Then

God in all His glory comes

into sight. A wondrous light

strikes us to the heart. All

is quiet and blissful.

Behold: there is no

judgement, no sinners, no

just men, neither great nor

small. There is no

punishment and no reward. A

feeling of overwhelming love

fills us with blissful

knowledge and illuminates

our earthly life."

Unlike his First Symphony,

which long remained

misunderstood, Mahler’s

Second took only a few years

to establish itself in the

concert hall. Richard

Strauss arranged for a

performance of the first

three movements at a

Philharmonic concert in

Berlin in March 1895, which

Mahler himself conducted,

but the critics afterwards

accused the young composer

of shattering his listeners’

eardrums with his ”noisy and

bombastic pathos” and

”atrocious, tormenting

dissonances". Undeterred, Mahler

organized the first

performance of the complete

work nine months later,

again in Berlin, but this

time including soloists and

chorus. By the end of the

evening he felt reassured by

the audience's enthusiastic

response, but with the next

morning’s newspapers came

renewed and bitter attacks.

Fortunately, the blow was

tempered by the enthusiasm

of such distinguished

admirers as the conductors

Arthur Nikisch and Felix

Weingartner and the composer

Engelbert Humperdinck. The

Munich premiüre,

during the winter of

1900/01, created something

of a stir, and when Mahler

conducted the Second in the

great Basle

Cathedral in 1903, another

performance organized by

Strauss, the work and its

composer were both

ecstatically received.

1. Allegro maestoso.

Mit durchaus ernstem und

feierlichem Ausdruck

[With deeply serious and

solemn expression]. With

this funeral march and the

eloquence of its thematic

material, the power of its

architectural structures,

the emotional thrust of its

inspiration and its

concision of thought, Mahler

assumes for the first time

the full stature of a

symphonist in the great

German tradition. The shadow

of Bruckner hovers over the

opening bars with a long

tremolando and a first

subject on the lower strings

that is 43 bars long. Yet

the composer’s distinctive

voice asserts itself in such

features as the

dominant-tonic melodic

intervals and the

alternation between major

and minor. The structure is

classical, with two main

subject groups, the second

of which, in E major

already hints at the work’s

optimistic conclusion and

the finale’s "Resurrection"

theme. Transposed to C

major, this same subject

also launches the first of

the movement's two

development sections with a

long, lyrical episode. In

the second of these, a new

element enters on six horns,

a solemn chorale related to

the Dies irae that

will later play a crucial

role in the final movement.

2. Andante moderato.

Sehr gemächlich.

Nie eilen [Very

leisurely. Never hurry]. Two

sections alternate in this

idyllic movement, so

different in style,

atmosphere and scale from

the first that Mahler

specified their separation

by a few minutes’ pause. The

first section is a graceful

landler in the major, the

second a triplet theme in

the minor. Mahler

was particularly proud of

the cello countermelody that

accompanies the principal

theme’s second exposition.

3. In ruhig fliessender

Bewegung [With a

gently flowing movement].

The tragic, or at least

pessimistic, conception of

this symphonic Scherzo seems

worlds away from the humour

of the Wunderhorn

song in which St. Anthony

preaches to the fishes, who

understand nothing of his

sermon and look on with a

glazed expression. Yet they

are sister works that use

identical musical material.

Two timpani strokes,

dominant-tonic, unleash the

Scherzo’s "senseless

agitation”, an uninterrupted

and intentionally monotonous

double ostinato in the

treble and bass. The bulk of

the material in the Trio in

C major is likewise borrowed

from the song. At the end of

the movement, the "cry of

despair" alluded to in the

symphony’s programme is

heard in a vast B flat minor

climactic tutti.

4. "Urlicht”. Sehr

feierlich, aber schlicht

(Choralmässig)

[Primeval Light. Very solemn

but simple (In the manner of

a chorale)]. After the

"tormenting” questions of

the opening movement and the

grotesque dance of the

Scherzo, humankind is freed

from uncertainty and doubt.

The Wunderhorn-Lied

brings with it the first ray

of a light that will shine

in glory at the end of the

finale. A solemn chorale,

gently stated on the brass,

affirms the innocent faith

of childhood; later on, an

expanded version of this

same ascending theme will

become the final movement's

”Resurrection" theme.

5. Im

Tempo des Scherzo. Wild

herausfahrend. [At the

same speed as the Scherzo.

In a wild outburst]. The

Scherzo’s "cry of despair"

is recalled, then answered (Sehr

zurückhaltend

[Very

restrained])

by a hesitant statement on

the horns of the emerging

"Resurrection" theme. There

follows a ”voice calling in

the wilderness”, again on

the horns, but this time

off-stage, before the

contours are once again

blurred by a descending

triplet figure that works

its way down through the

orchestra. The wind chorale

then heard against pizzicato

quavers (eighth notes) on

the strings announces some

of the characteristic

intervals of the

"Resurrection" theme, while

at the same time recalling

the Dies irae motif

heard in the opening

movement. But the time for

certainty has not yet come.

A long orchestral recitative

elaborates the theme of

human frailty and the

anxiety of God's creatures

as the much-feared hour

approaches. A reply comes

again in the form of a

chorale to which the lower

brass add a note of

solemnity. The heavens

brighten and the return of

the brass fanfare prepares

for a new statement of the

"Resurrection" theme, now

far more assertive. This

whole series of episodes is

linked together in a way

that follows dramatic,

rather than musical, rules

and constitutes a vast

prelude, almost 200 bars in

length.

An arresting crescendo on

the percussion introduces

the Allegro energico, a vast

symphonic free-for-all based

on most of the themes

already heard. A return of

the "cry of despair"

produces a startling effect

that is one of the earliest

instances of a typically

20th-century

"spatialization" effect:

off-stage brass repeatedly

superimpose fanfare motifs

on an impassioned recitative

that pursues its tireless

course, first in the cellos

and then in the violins. The

gnawing sense of anguish

grows more and more

insistent until the brass

enter with another

triumphant fanfare. Now at

last, in an atmosphere of

mystery and hope, the

radiant ”Resurrection" theme

appears in its glorious

complete form, marking the

beginning of the coda in

which chorus, soloists and

full orchestra come together

in a great cry of

jubilation.

One would search in vain in

this vast finale for the

infallible organization and

formal mastery of parallel

movements in Mahler’s other

symphonies; the form is

free, more dramatic perhaps

than symphonic, yet it is

hard to imagine a more

eloquent or suitable

conclusion for this work.

The Second Symphony’s

apotheosis recalls those

radiant "glories" that can

be seen shining above

Baroque altars in Austrian

churches. It overwhelms and

enthralls us, and puts all

our doubts to rest.

Henry-Louis

de La Grange

|

|

|