|

|

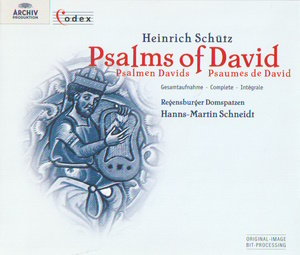

2 CD -

453 179-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

| 50

Jahre (1947-1997) - Codex II Serie - 3/5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Heinrich SCHÜTZ

(1585-1672) |

|

|

|

|

| Psalmen

Davids - für 2 bis 4 Chöre und

Instrumente (1619) |

|

|

130' 17" |

|

-

I. Psalm 110 - "Der Herr sprach zu

meinem Herren"

|

Capella à 5

(instrumental), Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c.

|

3' 17" |

|

1 - 1 |

| -

II. Psalm 2 - "Warum toben die

Heiden" |

Capella I/II à 4

(instrumental), Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

4' 09" |

|

1 - 2 |

-

III. Psalm 6 - "Ach, Herr, straf

mich nicht in deinem Zorn"

|

Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

4' 54" |

|

1 - 3 |

-

IV. Psalm 130 - "Aus der Tiefe ruf

ich, Herr, zu dir"

|

Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

4' 08" |

|

1 - 4 |

-

V. Psalm 122 - "Ich freu mich des,

das mir geredt ist"

|

Capella I/II à 4

(instrumental), Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

3' 40" |

|

1 - 5 |

-

VI. Psalm 8 - "Herr, unser

Herrscher, wie herrlich ist dein

Name"

|

Capella à 5

(instrumental), Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

3' 37" |

|

1 - 6 |

-

VII. Psalm 1 - "Wohl dem, der nicht

wandelt im Rat der Gottlosen"

|

Chorus I/II à 4

(vocal/instrumental), B.c. |

4' 42" |

|

1 - 7 |

-

VIII. Psalm 84 - "Wie lieblich sind

deine Wohnungen, Herr Zebaoth"

|

Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

6' 46" |

|

1 - 8 |

-

IX. Psalm 128 - Wohl dem, der den

Herren fürchtet"

|

Chorus I/II à 4

(vocal/instrumental), B.c. |

4' 36" |

|

1 - 9 |

-

X. Psalm 121 - "Ich hebe meine Augen

auf zu den Bergen"

|

Chorus I à 4

(Soli/Tutti), Chorus II à 4,

B.c. |

6' 45" |

|

1 - 10 |

-

XI. Psalm 136 - "Danket dem Herren,

denn er ist freundlich!"

|

Capella I/II à 4

(instrumental), Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

5' 04" |

|

1 - 11 |

-

XII. Psalm 23 - "Der Herr ist mein

Hirt"

|

Chorus I à 4

(Soli/Tutti), Chorus II à 4,

B.c. |

4' 04" |

|

1 - 12 |

-

XIII. Psalm 111 - "Ich danke dem

Herrn von ganzem Herzen"

|

Capella I/II à 4

(instrumental), Chorus I à 4

(Soli/Tytti), Chorus II à 4

(Soli/Tutti), B.c. |

5' 17" |

|

1 - 13 |

-

XIV. Psalm 98 - "Singet dem Herrn

ein neues Lied"

|

Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

5' 12" |

|

2 - 1 |

-

XV. Psalm 100 (Echo) - "Jauchzet dem

Herren, alle Welt!"

|

Chorus I à 4,

B.c., Chorus

II à 4, B.c. |

4' 03" |

|

2 - 2 |

-

XVI. Psalm 137 - "An den Wassern zu

Babel saßen wir und weineten"

|

Chorus I/II à 4,

B.c. |

4' 41" |

|

2 - 3

|

-

XVII. Psalm 150 - "Alleluja! Lobet

den Herren in seinem Heiligtum"

|

Capella I/II à 4

(instrumental), Chorus I à 4

(Soli/Tutti), Chorus II à 4

(Soli/Tutti), B.c. |

7' 20" |

|

2 - 4

|

-

XVIII. Concert - "Lobe den Herren,

meine Seele"

|

Chorus I à 4

(Soli/Tutti), Chorus II à 4,

B.c. |

4' 44" |

|

2 - 5

|

-

XIX. Motette - "Ist nicht Ephraim

mein teurer Sohn"

|

Chorus I/II à 4

(vocal/instrumental), B.c. |

4' 54" |

|

2 - 6

|

-

XX. Canzone - "Nun lob, mein Seel,

den Herren"

|

Capella I/II à 5

(instrumental), Chorus I à 4

(Soli/Tutti), Chorus II à 4,

B.c.

|

6' 20" |

|

2 - 7

|

-

XXI. Motette - "Die mit Tränen säen"

|

Chorus I/II à 4

(vocal/instrumental), B.c. |

3' 48" |

|

2 - 8

|

| -

XXII. Psalm 115 - "Nicht uns, Herr,

nicht uns" |

Chorus I à 4

(vocal/instrumental), Chorus II

à 4, Chorus III à 4

(vocal/instrumental), B.c. |

5' 10" |

|

2 - 9 |

| -

XXIII. Psalm 128 - "Wohl dem, der

den Herren fürchtet" |

Chorus I/II à 5

(vocal/instrumental), Capella

I/II à 4 (vocal), B.c. |

3' 38" |

|

2 - 10 |

| -

XXIV. Psalm 136 - "Danket dem

Herren, denn er ist freundlich!" |

3 trumpets,

timpani, Capella I à 5 (vocal),

Chorus I à 4 (Soli), Chorus II à

4 (vocal/instrumental), B.c. |

6' 52" |

|

2 - 11 |

| -

XXV. Concert - "Zion spricht: der

Herr hat mich verlassen" |

Capella I/II à 4

(vocal), Chorus I/II à 6

(vocal/instrumental), Basso

continuo |

5' 29" |

|

2 - 12 |

| -

XXVI. Concert - "Jauchzet dem

Herren, alle Welt!" |

Capella à 5

(vocal/instrumental), Chorus I à

5 (v/i), Chorus II à 2 (Soli,

B.c.), Chorus III à 5 (v/i),

B.c. |

7' 07" |

|

2 - 13 |

|

|

|

|

Regensburger

Domspatzen (Chor und Solisten)

Georg Ratzinger, Einstudierung

Instrumentalisten

- Holger

Eichhorn, Zink

-

Spiros Rantos, Richard Motz, Violine

alter Mensur

- Walter Stiftner, Käthe Wagner, Bass-Dulzian

- Eugen M. Dombois, Laute, Theorbe

- Michael Schäffer, Laute, Chitarrone

- Helga Storck, Harfe

- Eberhard Kraus, Hubert Gumz, Mathias

Siedel, General-Bass-Aussetzung

- Georg Ratzinger, Positiv I

- Gerd Kaufmann, Positiv II

Hanns-Martin SCHNEIDT, Musikalische

Leitung

|

Hamburger

Bläserkreis für alte Musik

- Detlef Hagge, Ulrich Brandhoff, Zink,

Natur-Trompete

- Eberhard Fiedler, Alt-Posaune

enger Mensur, Natur-Trompete

- Fritz Brodersen, Alt- und

Tenor-Posaune enger Mensur

- Harald Strutz, Tenor-Posaune

enger Mensur

- Hubert Gumz, Tenor-Posaune enger

Mensur, Serpent

- Walfried Kohlert, Bass.Posaune

enger Mensur

Ulsamer-Collegium

- Elza van der Ven, Diskant- und

Alt-Gambe

- Irmgard Otto, Tenorbass-Gambe

- Vimala Fries, Tenorbass-Gambe

- Josef Ulsamer, Diskant- und

Tenorbass-Gambe

- Laurenzius Strehl, Violone,

Viola bastarda

- Sebastian Kelber, Gerhard Braun, Renaissance-Traverflöte

- Dieter Kirsch, Laute, Theorbe

- Gyula Rácz, Kleine Kessel-Pauken

|

|

|

Edition:

Heinrich Schütz, Sämtliche Werke, ed.

Philipp Spitta, Vol. II & III,

Leipzig 1886/1887 (Breitkopf &

Härtel).

Revision of the score according to the

original print of the part bokks

(1619), in possession of the

Landesbibliothek Kassel: Arthur Simon |

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.

Emmeram, Regensburg (Germany) - 28

giugno / 10 luglio 1971 &

13/18 settembre 1972

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

Archiv

Produktion | 2722 007 | 3 LP | (p)

1972 | ANA | stereo

|

|

|

Edizione

"Codex"

|

|

Archiv

Produktion "Codex" | 453 179-2 |

durata 60' 59" · 69' 18" | LC 0113

| 2 CD | (p) 1996 | ADD | stereo

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Dr.

Andreas Holschneider

|

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Dr.

Gerd Ploebsch

|

|

|

Tonmeister

(Balance Engineer) |

|

Klaus

Hiemann

|

|

|

Cover |

|

King

David playing a harp (detail of

the initial "B", from the Bamberg

Psalter, 13th century)

|

|

|

Note |

|

Original-Image-Bit-Processing

- Added presence and brilliance,

greater spatial definition |

|

|

|

|

|

ORIGINAL

EDITIONS

3 LP - 2722 007 - (p) 1972

|

Treasures

from Archiv Produktion’s

Catalogue

A rare and valuable collection of

documents is the pride of any

library or archive. CODEX, Archiv

Produktion’s new series, presents

rare documents in sound from 50

years of pioneering recording.

These recordings have been

digitally remastered using

original-image bit-processing

technology and can now be

appreciated in all the richness of

their original sound-image. They

range from the serene counterpoint

of a Machaut, the intensely

spiritual polyphony of a Victoria,

to the imposing state-music of a

Handel.

For the artists on Archiv

Produktion recordings, a constant

aim has been to rediscover the

musical pulse of past times and to

recreate the spirit of past ages.

In this sense each performance

here - whether by Pro Musica

Antiqua of Brussels in the 1950s,

the Regensburg Domchor in the

1960s, or Kenneth Gilbert and

Trevor Pinnock in the 1970s - made

a vital contribution to the

revival of Early Music in our

time.

CODEX highlights recordings that

were unique in their day, many of

them first recordings ever of this

rare and remarkable repertoire,

now appearing for the first time on

CD. A special aspect of the

history of performance in our

century can now be revisited, as

great moments from Archiv

Produktion’s recording history are

restored and experienced afresh.

Dr.

Peter Czornyi

Director,

Archiv Produktion

HEINRICH SCHÜTZ'S "PSALMES OF

DAVID" (1639)

Heinrich Schütz’s Psalmen

Davids first appeared in

print in 1619, two years after

their then 32-year-old composer

had taken up his official

appointment as Hofkapellmeister in

Dresden. It is presumably this

volume, described by later editors

as the composer’s op. 2, to which

the now 66-year-old Schütz was

referring when he wrote

retrospectively in 1651: “When I

first returned to Germany from

Italy in 1613, I resolved that for

the next few years I would keep to

myself with the good foundations

that I had now laid in music,

going into hiding with them, as it

were, until I had refined them

somewhat further still and was

then able to distinguish myself

properly by bringing forth a

worthy piece of work.”

Schütz had spent the years between

1609 and 1613 in Venice, studying

with Giovanni Gabrieli. On his

return to Germany, he was expected

to complete his studies in law,

which he had begun in 1608, but

his love of music soon gained the

upper hand, and so his former

protector, the Landgrave Moritz of

Hesse, created the post of second

court organist specially for him

at Kassel. With hindsight, Moritz

must later have come to regret

lending out his protégé for a

baptism at the Dresden court,

since the Elector Johann Georg I

of Saxony thereafter left no stone

unturned in his attempts to lure

the young Schütz to Dresden,

finally persuading “Sagittarius”

(as Schütz was called in Latin

documents of the time) to become

his de facto

Kapellmeister.

Two major events soon offered

Schütz an opportunity to show the

electoral Kapelle in a new and

splendid light: the first, in July

1617, was a state visit by the

Emperor Matthias and his vast

entourage (including the famous

military commander, Albrecht von

Wallenstein), the second the

elaborate celebrations held to

mark the centenary of the

Reformation on 31 October

1617. Two of Schütz’s Psalmen

Davids - settings of Psalms

98 and 100 respectively - are

known to have been performed on

this second occasion.

The entire collection of psalms

must have been printed during the

first half of 1619 at the latest.

Schütz dated his foreword l June,

thereby providing a terminus

ante quem. This was the day

on which he married Magdalena

Wildeck, the daughter of a court

official described in contemporary

documents as responsible for

keeping an account of the

elector’s land-tax and tax on

alcohol. The brilliance of

Schüty's large-scale concerti

per choros recalls similar

pieces by Giovanni Gabrieli and

was well calculated to suggest a

composer who, delighting in life

and his creative gifts, had an

outstanding future ahead of him.

Yet these yea-saying works, with

their rich-toned sonorities, were

in all too stark a contrast with

the subsequent course of events.

Schütz’s wife died after only six

years of marriage; and the

increasing hardships of the Thirty

Years War inevitably led to a

reduction in the Kapelle’s

strength and soon put an end to

lavish music-making.

Schütz sent copies of the 1619

print, together with invitations

to his wedding, to addresses all

over Germany, including with them

dedicatory poems by a number of

his poetically inspired fiiends

that praise in the effusive terms

of Baroque rhetoric a musician who

was compared not so much to

Orpheus (who famously caused the

very stones to dance) as to the

Archangel Raphael, who was

permitted to sing in God’s ear.

We can only speculate on the

extent to which these psalms were

ever performed in church. Although

there were still services of

thanks-giving and celebrations of

peace when festive music was

required, the impending chaos of

war can scarcely have favoured

their regular performance and, to

the extent that musical settings

of psalms were needed at all, the

technically and musically simpler

Becker Psalter was the obvious one

for Schütz’s contemporaries to

fall back on, at least from 1628

onwards. This was a collection of

four-part settings based on the

popular psalm paraphrases of the

Leipzig theologian Cornelius

Becker that soon acquired

literally canonical status at

services at the Dresden court. In

1653, in one of the final petitions

that he wrote in his attempt to

gain an official pension, Schütz

expressed his intention of setting

Luther’s prose psalter “in such a

way that the common people may

easily be able to learn these

melodies and sing with them in

church”. But he never realized

this aim.

Polyphonic settings of the psalms

are first recorded in the 14th

century. It was for these settings

that falsobordone writing

was developed, a style that Schütz

himself occasionally employed (a

particularly impressive example

occurs in his setting of Psalm 84,

where it is used over three whole

verses, beginning with the words:

“Lord God of hosts, hear my

prayer”). It was easier to set a

densely worded text in falsobordone

than in the so-called motet style.

Not until around 1500 do we find

Latin psalm motets, when (to quote

Ludwig Finscher) “the newly

awakened expressive urge on the

part of the composers associated

with Josquin encouraged them to

take an interest in the idea of

personal confession implied by the

words of the psalms”. Thomas

Stoltzer (c.1480/85-1526) was the

first composer to provide musical

settings of Luther’s German

translation of the psalms.

A century or more was to pass

before the Latin psalm motet lost

its hegemony in Protestant Europe

and allowed composers such as

Sethus Calvisius, Michael

Praetorius, Melchior Franck and,

finally, Schütz himself to assert

the rival claims of the German

psalm motet and German vocal

concerto. The years that followed

also witnessed the composition of

some notable psalms by north

German masters of the cantata such

as Tunder, Böhm and Buxtehude and,

above all, by Johann Sebastian

Bach; yet the most striking

development at this time was the

emergence of a hybrid form in

which the complete text of the

individual psalms was interwoven

with popular proverbs, exegetical

observations and hymns.

It is clear from this development

that, in keeping with the spirit

of the age, the psalms were

becoming increasingly divorced

from their liturgical context,

allowing them to assert their

claims to artistic autonomy. As

Hofkapellmeister at the Lutheran

court of Dresden, Schütz was also

responsible for the music

performed during church services,

but, unlike the older Kantors and,

indeed, unlike Bach a century

later, he did not write his psalm

settings simply in order to meet

the terms of his contract.

Schütz’s settings were, in part,

an act of self-expression on the

part of a composer who was now

fully aware of his genius, while

still being designed to be

performed within the context of a

church service, even if they

consciously went far beyond the

traditional framework of the

liturgy. In his accompanying

letter to the town council in

Frankfurt am Main, Schütz drew

explicit attention to the fact

that his work was intended for

spiritual and ecclesiastical use,

and we have no reason to suppose

that he was merely falling back on

the usual pious formulas. Here he

explains: “I have set to music

some of the psalms of the king and

prophet David, in the form in

which they were conceived by him,

and have done so, moreover, out of

special devotion, in honour of

God, just as everyone in his

calling is obliged, first and

foremost, to guide and direct his

fellow men, and, in having them

printed, I commend them to, and

solicit, all of pious heart and

Christians everywhere.”

From the outset, psalms were a

regular part of the Christian

liturgy, including, of course, two

typically Western forms of the

liturgy that developed in the

Middle Ages, namely, the Mass and

Hours. The Lutheran Reformation

consciously retained these forms,

while at the same time simplifying

and abbreviating them. In

consequence, psalms still had a

legitimate place in the main

Lutheran service, where they

featured at least as an Introit or

Communion psalm. At Vespers they

would be performed after the

lngressus. Schütz’s choice of

psalms was dictated, at least in

part, by the Proprium de

tempore, in other words, by

the order of services within the

annual cycle. Psalms 2, 8, 98, 100

and 110 were among those

prescribed for Advent, Christmas

and Epiphany, while the

penitential Psalms 6 and 130,

together with Psalm 137, were

intended for Lent and for days of

repentance. Psalms 111, 23 and 98

were sung on Maundy Thursday and

during Easter Week, while Psalms

100, 103, 136 and 150 and the

sections of the psalm used in the

final Concert could be

performed on anniversaries and

days of thanks-giving.

The fact that Schütz included

other Biblical texts in his Psalmen

Davids and that psalms were

also performed at services in

Dresden after the Gospel reading,

after the sermon and, in the case

of Vespers, after the Magnificat

suggests that, in keeping with the

increasingly discursive style of

oratory of Dresden’s famous court

preachers, music was gradually

breaking free from its strict

liturgical ties. Concertante music

could claim to be an independent

interpreter of the word of God

and, as such, to serve the aims of

the liturgy. This not only

justifies today’s practice of

performing Schütz’s psalms in the

concert hall as works of art in

their own right, it also suggests

the possibility of reintegrating

them into present-day services,

where attempts have already been

made to recombine the traditional

elements that have been displaced

over the years and to place them

in a new functional context.

Friedrich

Kalb (1972)

(Translation:

Stewart Spencer)

|

|

|

|