|

|

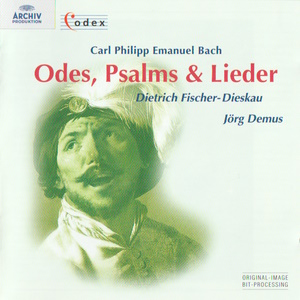

1 CD -

453 168-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

50

Jahre (1947-1997) - Codex I Serie - 7/10

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ODES, PSALMS

& LIEDER

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carl

Philipp Emanuel BACH (1714-1788)

|

Über

die Finsternis kurz vor dem Tod

Jesu, Wq 197 |

|

2' 14" |

1

|

|

Der

Frühling, Wq 197

|

|

1' 44" |

2 |

|

Pröfung

am Abend, Wq 194

|

|

4' 06" |

3 |

|

Morgengesang,

Wq 194

|

|

1' 56"

|

4 |

|

Bitten,

Wq 194

|

|

1' 27" |

5 |

|

Trost

der Erlösung, Wq 194

|

|

1' 39" |

6 |

|

Fantasia

in C minor, Wq 63, 6 ("Probestück")

*

|

|

5' 47" |

7 |

|

Passionslied,

Wq 194

|

|

5' 36" |

8 |

|

Die

Güte Gottes, Wq 194

|

|

2' 03" |

9 |

|

Abendlied,

Wq 194

|

|

2' 12" |

10 |

|

Wieder

den Übermut, Wq 194

|

|

3' 50"

|

11 |

|

Demut,

Wq 194

|

|

2' 19" |

12 |

|

Fantasia

in C major, Wq 61, 6 *

|

|

6' 17" |

13 |

|

Der

19. Psalm, Wq 196

|

|

2' 04" |

14 |

|

Der

130. Psalm, Wq 196 |

|

2' 28" |

15 |

|

Weihnachtslied,

Wq 197

|

|

2' 26" |

16 |

|

Jesus

in Gethsemane, Wq 198

|

|

3' 26" |

17 |

|

Der

Tag des Weltgerichts, Wq 197

|

|

2' 19" |

18 |

|

Der

148. Psalm, Wq 196 |

|

0' 52" |

19 |

|

|

|

|

Dietrich

FISCHER-DIESKAU, baritone

Jörg DEMUS, tangent

piano (Tangentenflügel)

Colin TILNEY, clavichord

*

|

Extracts from the

collections:

- Herrn Professor Gellerts Geistliche

Oden und Lieder mit Melodien, Berlin

1958 (Wq 194)

- Herrn Doctor Cramers übersetzte

Psalmen mit Melodien zum Singen bey

dem Claviere, Leipzig 1774 (Wq 196)

- Herrn Christoph Christian Sturms,

Hauptpastors an der Hauptkirche St.

Petri und Scholarchen in Hamburg,

Geistliche Gesänge mit Melodien zum

Singen bz dem Claviere, Hamburg 1780

(Wq 197) / Zweyte Sammlung, Hamburg

1781 (Wq 198)

- Clavier-Sonaten und freye Fantasien,

nebst einigen Rondos für Fortepiano

für Kenner und Liebhaber, 66.

Sammlung, Hamburg 1786 (Wq 61, 6)

18 Probestücke in 6 Sonaten. Beigabe

zum Versuch über die wahre Art, das

Clavier zu Spielen. Teil 1, Berlin

1753 (Wq 63, 6)

Publishers:

- C.P.E. Bach, 30 geistliche Lieder:

Edition Peters, ed. H. Roth;

- Fantasias: Breitkopf & Härtel,

ed. L. Hoffmann-Erbrecht

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

St.-Michaelis-Heim,

Berlin-Grunewald (Germania) -

20-22 novembre 1969 (Odes)

Studio Hamburg, Hamburg-Rahlstedt

(Germania) - 1-5 dicembre 1975

(Fantasias)

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

-

Archiv Produktion | 2533 058 | 1

LP | (p) 1971 | ANA | (Odes)

- Archiv Produktion | 2533 326 | 1

LP | (p) 1976 | ANA | (Fantasias)

|

|

|

Edizione

"Codex"

|

|

Archiv

Produktion "Codex" | 453 168-2 |

durata 55' 00" | LC 0113 | 1 CD |

(p) 1996 | ADD | stereo

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Rainer

Brock (Odes); Dr. Andreas

Holschneider (Fantasias)

|

|

|

Recording

Producer and Tonmeister |

|

Hans-Peter

Schweigmann (Odes); Heinz

Wildhagen (Fantasias)

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Hendrick

Ter Brugghen "Duo" (detail),

Louvre, Paris

|

|

|

Art Direction

|

|

Fred

Münzmaier

|

|

|

Note |

|

Original-Image-Bit-Processing

- Added presence and brilliance,

greater spatial definition |

|

|

|

|

|

ORIGINAL

EDITIONS

1 LP - 2533 058 - (p) 1971

1 LP - 2533 326 -

(p) 1976

1 LP - 2533 326 -

(p) 1976

|

Treasures

from Archiv Produktion’s

Catalogue

A rare and valuable collection of

documents is the pride of any

library or archive. CODEX, Archiv

Produktion’s new series, presents

rare documents in sound from 50

years of pioneering recording.

These recordings have been

digitally remastered using

original-image bit-processing

technology and can now be

appreciated in all the richness of

their original sound-image. They

range from the serene counterpoint

of a Machaut, the intensely

spiritual polyphony of a Victoria,

to the imposing state-music of a

Handel.

For the artists on Archiv

Produktion recordings, a constant

aim has been to rediscover the

musical pulse of past times and to

recreate the spirit of past ages.

In this sense each performance

here - whether by Pro Musica

Antiqua of Brussels in the 1950s,

the Regensburg Domchor in the

1960s, or Kenneth Gilbert and

Trevor Pinnock in the 1970s - made

a vital contribution to the

revival of Early Music in our

time.

CODEX highlights recordings that

were unique in their day, many of

them first recordings ever of this

rare and remarkable repertoire,

now appearing for the first time on

CD. A special aspect of the

history of performance in our

century can now be revisited, as

great moments from Archiv

Produktion’s recording history are

restored and experienced afresh.

Dr.

Peter Czornyi

Director,

Archiv Produktion

“... He has succeeded in

investing these brief song

settings with a very real

significance”

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s songs

had long since ceased to be part

of the general musical

consciousness when the leading

Swiss composer and teacher, Hans

Georg Nägeli, contributed a

generous assessment of them to the

Allgemeine musikaliscbe Zeitung

in 1811: “As experienced as any

other in the scientific branch of

art and as accomplished in the

artistic branch, while at the same

time incomparably intelligent and

imaginative, he [Carl Philipp

Emanuel Bach] has succeeded in

investing these brief song

settings with a very real

significance that even today’s song

composers would seek in vain to

surpass.” Even as Nägeli was

penning these lines, Franz

Schubert was setting the first of

his 600 lieder, Schiller’s Der

Mädchen Klage.

Nägeli rightly draws attention to

the singularity and originality of

Bach’s songs. The composer’s first

such collection - a setting of

Christian Fürchtegott Gellert’s

anthology of sacred odes and hymns

- appeared in 1758, amid the

depredations of the Seven Years

War. Published under the title Herrn

Professor Gellerts geistliche

Oden und Lieder mit Melodien,

it turned him overnight into one

of Germany’s most highly regarded

song composers. The fact that the

edition was reprinted no fewer

than five times during its

composer’s lifetime is in itself

sufficient to underline the

extraordinary popularity of these

Gellert settings.

Berlin was the centre of the

German art song in the years

around 1750. Agricola, Kirnberger,

Marpurg, Quantz and Carl Philipp

Emanuel himself were only the most

prolific of the many composers who

turned, by preference, to the

poetry of Gellert, Hagedorn,

Gleim, Gräfe, Ramler and Lessing.

The majority of their songs were

secular in character and,

technically speaking, relatively

simple, so that amateur musicians

could easily sing them. The

Gellert songs, by contrast, are

rather more demanding, as is clear

from a review that appeared in the

Allgemeine Deutsche Bibliothek

in 1766: “Nor is there any

mistaking Mr. Bach’s fiery and

imaginative spirit in these odes.

Although they really seem to have

been conceived more in terms of

the keyboard than the voice, a

well-trained and technically

competent singer will none the

less find ample opportunity to

improve his or her execution of

small ornaments, to practise the

accurate rendition of certain

difficult melodic configurations

and, in general, to develop his or

her powers of expression.”

Influenced, as he was, by

Pietistic ideas, Bach wrote these

songs with the specific aim of

being both edifying and

instructive. In Bitten,

the setting of the text is largely

syllabic, with only a few

significant exceptions. The words

“so weit die Wolken gehen” (as far

as the clouds go) are set

melismatically, no doubt in an

attempt to underscore the poetic

image, while the sense of contrast

contained within the strophe as a

whole, notably at the words “Herr,

meine Burg, mein Fels” (Lord, my

fortress, my rock), is reflected

in the detailed musical setting,

with its emphatic repeated notes

underscored by agitated

accompanying figures and firmly

anchored in G major, before the

music abruptly modulates back to

the opening key of E minor at the

words “Vernimm mein Flehn" (Hear

my entreaty) and finally dies away

on a rapt pianissimo.

Almost 50 years later Beethoven

would adopt a totally different

series of compositional solutions

when setting this same poem. But

that he was familiar with Bach’s

version is beyond question, so

striking are the parallels between

individual passages.

Bach‘s close collaboration with

his various poets lasted many

years and continued to bear fruit

during his years in Hamburg. Time

and again, however, it was the

poets of the Göttinger Hain - a

league of student-poets enamoured

of Klopstock’s new and emotional

brand of poetry - to whom the much

older composer returned and who,

in turn, approved of his manner of

setting their poems. Bach not only

wrote many secular songs, some of

which are almost popular in tone,

he also composed numerous sacred

songs. In 1774 he published, at

his own expense, Herrn Doctor

Cramers übersetzte Psalmen mil

Melodien zum Singen bey dem

Claviere (Dr. Cramers Psalms

in Translation, with Melodies to

Sing at the Keyboard), settings of

words by the Kiel professor of

theology, Johann Andreas Cramer.

Bach’s ability to capture the tone

of contemporary Empfindsamkeit

is clear from a whole series of

enthusiastic reviews of these

musical miniatures.

When Christoph Christian Sturm was

appointed preacher at St. Peter’s

in Hamburg in 1777, Bach wrote an

introductory piece to welcome him.

Their collaborative Geistliche

Gesange of 1780 and 1781

were so successful that no fewer

than 224 printed copies of the

first part were ordered in Hamburg

alone. In her authoritative study

of Bach’s songs, Gudrun Busch

offers an admirable assessment of

both collections: “Experimentation

and a conscious desire to be

different are avoided. All this

reflects the contemplative

religiosity of Sturm’s texts. The

most powerful expressivity is

concentrated in the highly

successful Passion hymns, which

provide further evidence of Bachs

distinctive style in terms of

chromaticism, harmonic writing and

declamation.”

At the same time that he was

devoting his creative energies to

songs such as these, with their

profoundly internalized moods,

Bach was also writing highly

virtuoso keyboard music. The

fantasia offered him the

possibility, as he himself said,

to express the changes “from one

affect to another with surprising

speed”. As a “trial effort” he did

this out for the first time in 1753

in the C minor Fantasia included

in his Versusch über die wahre

Art, das Clawier zu spielen

(“Essay on the True Art of Playing

Keyboard Instruments”). Thirty

years later, in his collections

“for connoisseurs and amateurs”,

he returned to the genre. The

expressive contrasts found in the

C major Fantasia from the sixth

collection could hardly be more

extreme and inevitably recall

Reichardt’s description of Bach

as a “serious humorist”.

Hans-Günter

Ottenberg

(Translation:

Stewart Spencer)

The Instruments

The tangent piano (Tangentenflügel)

is a keyboard instrument of the

18th century. Its position within

the history of the keyboard

instruments is between the

clavichord and the fortepiano. The

first types of the Tangentenflügel

produced their sound like the

clavichord, but the shape of the

“tangent” at the rear end of the

keys was different: instead of the

vertical brass blade there was a

jack-shaped wooden pin to strike

the string. While the strings of

the clavichord are set up at right

angles to the keyboard, those of

the Tangentenflügel are

arranged in a line with the

relevant finger-keys and give the

instrument the shape of a grand

piano. This had already been the

shape of the harpsichord, and it

prevailed in the further

development of the keyboard

instruments (from the different

kinds of the hammerklavier to the

grand piano of today). In the

course of the 18th century the

mechanism of the Tangentenflügel

was refined, among others by

Christoph Gottlieb Schröter of

Dresden, but only towards the end

of the century did the instrument

gain some popularity for its “very

strong and sumptuous sound”

(Heinrich Christoph Koch, Musikalisches

Lexikon, Frankfurt-on-Main,

1802, p. 1493). The sound was now

produced by a tangent made of wood

(also later covered with leather)

striking the string by means of an

intermediate lever, a second

wooden pin attached at the rear

end of the key muted the string.

This mechanism was also used by

Franz Jakob Späth and Christoph

Friedrich Schmahl of Regensburg

who made Tangemtenflügel

from about 1751 to 1812. The Tangentenglügel

used in this recording was made by

them in 1793. The instrument was

loaned by the Museum of Musical

Instruments of the State Institute

for Musical Research, Preussischer

Kulturbesitz, Berlin.

The clavichord heard in this

recording was made by Hieronymus

Albrecht Hass, Hamburg, in 1742.

Hass (1721-85) came from a

well-known Hamburg family of

instrument makers who concentrated

almost exclusively on the

production of keyboard instruments

and are known to have maintained a

workshop in Dresden as well as in

Hamburg.

The instrument is an unfretted

clavichord with a compass of five

octaves (F1-f3). From F1-d there

are three unison strings to a

note, from d#-f3 pairs of strings.

In 1953 the instrument was

restored by Hans Lengemann. Then,

in 1975, a complete examination

and restoration was carried out by

Martin Skowroneck of Bremen.

During restoration in 1975 the

strings were replaced completely;

those now used are composed of a

copper alloy.

Archiv Produktion wishes the thank

the Museum für Hamburgische

Geschichte for the loan of this

valuable instrument, and Frau Dr.

Gisela Jaacks for her help and

co-operation.

For technical resasons, the

transfer has been made at a high

level. In order to obtain natural

reproduction corresponding to the

original quiet sound, the volume

should be turned down as low as

possible.

|

|

|

|