|

|

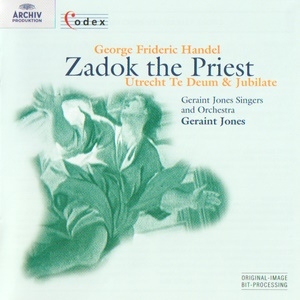

1 CD -

453 167-2 - (p) 1996

|

|

50

Jahre (1947-1997) - Codex I Serie - 6/10

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

George

Fridderic HANDEL (1685-1759)

|

"Utrecht"

Te Deum & Jubilate (HWV

278 & 279)

|

|

|

|

|

-

"We praise thee, O God" - (Chorus)

|

|

4' 30" |

1 |

|

-

"To thee all Angels cry aloud" - (Soli

& Chorus) - "To thee

Cherubin and Seraphin" - (Soli

& Chorus)

|

|

2' 45" |

2 |

|

-

"The glorious company of the

Apostles" - (Soli & Chorus)

- "Thou art the King of Glory" - (Chorus)

|

|

5' 11" |

3 |

|

-

"When thou took'st / When thou hadst

overcome" - (Soli & Chorus)

- "Thou sittest at the night hand of

God" - (Chorus)

|

|

3' 58" |

4 |

|

-

"We believe that thou shalt come" -

(Soli & Chorus)

|

|

3' 09" |

5 |

|

-

"Day by day" - (Chorus) /

"And we worship thy Name" - (Chorus)

|

|

2' 26" |

6 |

|

-

"Vouchsafe, O Lord" - (Soli

& Chorus)

|

|

3' 23" |

7 |

|

-

"O Lord, in thee have I trusted" - (Chorus)

|

|

1' 20" |

8 |

|

(Jubilate) |

|

|

|

|

-

"O be joyful in the Lord" - (Solo

& Chorus)

|

|

2' 10" |

9 |

|

-

"Serve the Lord with gladness" - (Chorus)

|

|

2' 13" |

10 |

|

-

"Be ye sure that the Lord he is God"

- (Duo)

|

|

2' 34" |

11 |

|

-

"O go your way into his gates" - (Chorus)

|

|

2' 49" |

12 |

|

-

"For the Lord is gracious" - (Trio)

|

|

3' 29" |

13 |

|

-

"Glory to be the Father" - (Chorus)

|

|

5' 42" |

14 |

|

Zadok

the Priest (Coronation Anthem

No. 1, HWV 258)

|

|

|

|

|

-

"Zadok the Priest"

|

|

2' 12" |

15 |

|

-

"And all the people rejoic'd"

|

|

0' 51" |

16 |

|

-

"God save the King"

|

|

3' 02" |

17 |

|

|

|

|

Ilse Wolf, soprano

Helen Watts, contralto

Wilfried Brown, Egar Fleet,

tenor I / II

Thomas Hemsley, bass

GERAINT JONES SINGERS AND

ORCHESTRA

- Winifred Robert, violin

- Harold Jackson, Bernard Brown, trumpet

- Geoffrey Gilbert, flute

- Edward Selwyn, Michael Dobson, oboe

- Ronald Waller, Anthony Judd, bassoon

- Ambrose Guntlett, violoncello

- Edward Merrett, double bass

- Alan Harverson, organ

Geraint JONES

|

Instruments:

- Violin: J. B. Guadagnini, 18th

Century

- Trumpets in D: Besson & Co.

London 1) 1950, 2) 1954

- German Flute: Verne Powell, Boston,

USA, 1957

- Oboes: 1) Louis, London, 1935, 2)

Howarth, T. W., London, 1947

- Bassoons: Heckel, Biebrich, 1) 1951,

2) 1939

- Violoncello: Matteo Goffriller,

Venice, 1729

- Double Bass: Gaspar da Salo at

Brescia, c. 1560/70

- Positive Organ: Abraham adcock and

John Pether, c. 1750

Publishers: Ausgabe der deutschen

Händelgesellschaft, Leipzig 1869 (ed.

F. Chrysander)

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Walthamstow

Town, London (Inghilterra) - 30

giugno / 2 luglio 1958

|

|

|

Original

Editions |

|

-

Archiv Produktion | 14 124 APM | 1

LP | (p) 1949 | ANA

|

|

|

Edizione

"Codex"

|

|

Archiv

Produktion "Codex" | 453 167-2 |

durata 51' 58" | LC 0113 | 1 CD |

(p) 1996 | ADD | mono

|

|

|

Executive

Producer |

|

Dr.

Hans Hickmann

|

|

|

Recording

Producer |

|

Dr.

Ursula von Rauchhaupt

|

|

|

Balance

Engineer (Tonmeister) |

|

Harald

Baudis

|

|

|

Cover |

|

Fresco

bz andrea Poyyo, St. Ignayio, Rome

(detail) - © Mauro Pucciarelli,

Rome

|

|

|

Art Direction

|

|

Fred

Münzmaier

|

|

|

Note |

|

Original-Image-Bit-Processing

- Added presence and brilliance,

greater spatial definition |

|

|

|

|

|

ORIGINAL

EDITIONS

1 LP - 14 124 APM - (p) 1959

|

Treasures

from Archiv Produktion’s

Catalogue

A rare and valuable collection of

documents is the pride of any

library or archive. CODEX, Archiv

Produktion’s new series, presents

rare documents in sound from 50

years of pioneering recording.

These recordings have been

digitally remastered using

original-image bit-processing

technology and can now be

appreciated in all the richness of

their original sound-image. They

range from the serene counterpoint

of a Machaut, the intensely

spiritual polyphony of a Victoria,

to the imposing state-music of a

Handel.

For the artists on Archiv

Produktion recordings, a constant

aim has been to rediscover the

musical pulse of past times and to

recreate the spirit of past ages.

In this sense each performance

here - whether by Pro Musica

Antiqua of Brussels in the 1950s,

the Regensburg Domchor in the

1960s, or Kenneth Gilbert and

Trevor Pinnock in the 1970s - made

a vital contribution to the

revival of Early Music in our

time.

CODEX highlights recordings that

were unique in their day, many of

them first recordings ever of this

rare and remarkable repertoire,

now appearing for the first time on

CD. A special aspect of the

history of performance in our

century can now be revisited, as

great moments from Archiv

Produktion’s recording history are

restored and experienced afresh.

Dr.

Peter Czornyi

Director,

Archiv Produktion

HANDEL: "UTRECHT" TE DEUM AND

JUBILATE - ZADOK THE PRIEST

Handel arrived in London in 1710

and pursued a virtually continuous

career there for the rest ofhis

life. Most of his music was

written for the theatre, but he

also composed English church music

to enhance services marking

particular national events. He

became the composer of music for

principal court or national

celebrations, though we have no

reason to doubt that his church

music also expressed religious

sentiments that came naturally to

the composer. He also seems to

have revelled in the grand effects

that could be achieved from the

large (in 18th-century terms)

forces that were gathered for

state occasions in London. In this

respect, the works included on

this recording marked a new

development in English church

music: in them, traditional

English texts for national

religious celebrations received

forceful setting in the version of

the late Baroque musical style

that Handel made especially his

own. This style is apparent in the

Latin psalms that Handel had

composed in Rome in 1707, and

indeed probably had its roots even

earlier in German works that are

now lost: but it was in London,

and in the English language, that

he found the opportunities to

bring the style to its most

developed and vivid form.

The Peace of Utrecht, ending the

European War of the Spanish

Succession, fell at an interesting

period in Handel’s career. From

the English perspective, active

engagement during the first decade

of the 18th century - the period

of the Duke of Marlborough’s

famous victories - had given place

to a political change that

involved withdrawal from the war.

This change of policy from Queen

Anne’s government was looked upon

with disfavour by her allies in

the war, including the Hanoverian

interest. Handel’s ready

participation in the celebrations

of the Peace in 1713 indicated his

commitment to his new-found home

in London, and probably explains

the various anecdotes about the

initial coolness with which the

composer was regarded by the

Elector of Hanover when he came to

succeed as King George I of Great

Britain upon Anne’s death the next

year. Handel composed the

“Utrecht” music early in 1713: his

only previous piece of English

church music had been a short

“verse” anthem for the Chapel

Royal composed towards the end of

1712. He may well have looked at

the published score of Purcell’s D

major Te Deum and Jubilate from

1694, to give him a general idea

of the sort of setting that the

texts might receive in a full

ceremonial layout for soloists,

chorus and orchestra. But Handel’s

version is on a much bigger scale

than Purcell’s, and in a much more

powerful style: it is also a

remarkable achievement for a

composer whose contact with the

English language was still

relatively recent. The state

service in celebration of the

Peace, which eventually took place

in July 1713 at St. Paul’s

Cathedral, was preceded by a

number of public rehearsals, at

which the music appears to have

been well received: one newspaper

report said that it was “much

commended by all that have heard

the same, and are competent judges

therein”. It seems certain that

the “competent judges” had heard

nothing quite like it before: with

the “Utrecht” music Handel set up

a new model for ceremonial English

church music.

The coronation service for King

George II and Queen Caroline in

October 1727 provided the next

occasion on which Handel could

exercise this grand style:

according to one report, he had 40

voices and 160 instruments at his

disposal. It seems that Handel’s

musical contribution to the

coronation service was the result

of a specific invitation or command

from the Royal Family: the leading

Chapel Royal composer, William

Croft, had died a couple of months

before the coronation, and the

King seems to have used his

influence in Handel’s favour, in

preference to the leading London

church musician Maurice Greene,

who eventually filled Croft’s

place at the Chapel Royal. Handel

had not written any music for the

previous coronation, of King

George I in 1714. At that date he

was still a German, though

receiving a British pension

granted by Queen Anne, possibly

largely as a reward after the

“Utrecht” music. By the time of

the coronation in 1727, however,

his situation was different: in

1723 he had received a (largely

honorary) court appointment as

Composer for the Chapel Royal, and

one of King George I’s last acts

in 1727 had been to sign a

parliamentary bill naturalizing

Handel as a British citizen.

According to an anecdote later

recorded by Charles Burney, Handel

was sent the texts of the anthems

for the coronation in 1727 by the

Bishops and responded, “I have

read my bible very well, and shall

choose for myself.” In fact the

coronation liturgy was traditional

even to the texts of the anthems,

and the form of service used in

1727 was very similar to that used

in previous coronations: the words

that Handel set varied only in

minor details from ones that

composers had set in the past. The

scale and style of Handel’s music

in 1727 was entirely new, however,

and nowhere more so than in Zadok

the Priest, the anthem that

traditionally accompanied the

anointing of the King. The

cumulative effect of the

curtainraising orchestral

introduction, the dramatic entry

of the full choir divided in seven

parts, and the concentration of

the subsequent blocks ofmusical

sound for “God save the King”,

must have been thrilling for its

original listeners. It is not

surprising that this anthem has

become a “classic”, used at every

subsequent British coronation.

Handel himself contributed to the

establishment of the anthem’s

popularity by including part of it

in the score of his first theatre

performances of English oratorio

five years after the coronation:

he would probably have been

neither surprised nor displeased

that this has become one ofhis

best-known works.

Donald

Burrow

|

|

|

|