|

|

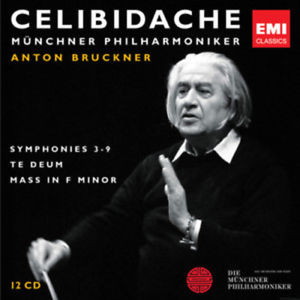

12

CD's - 0 85578 2 - (c) 2011

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

No. 3 in D minor - 1888-89

Version, ed. Nowak

|

|

66' 41" |

CD 1 |

| -

1. Sehr langsam, misterioso |

25' 07" |

|

|

| -

2. Adagio (bewegt) quasi andante |

16' 38" |

|

|

| -

3. Ziemlich schnell |

7' 46" |

|

|

| -

4. Allegro |

15' 04" |

|

|

| -

Applause |

1' 10" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 4 in E flat major "Romantic"

- ed. Haas |

|

79' 11" |

CD 2 |

| -

1. Bewegt, nicht zu schnell |

21' 55" |

|

|

| -

2. Andante quasi allegretto |

17' 35" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo: Bewegt - Trio: Nicht zu

schnell. Jeinesfalls schleppend |

11' 03" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu

schnell |

27' 52" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

No. 5 in B flat major - 1878

Version, ed. Haas

|

|

89' 53" |

|

| -

Applause |

0' 44" |

|

|

| -

1. Adagio - Allegro |

22' 43" |

|

CD 3 |

| -

2. Adagio - Sehr langsam |

24' 14" |

|

CD 3 |

-

3. Scherzo: Molto vivace (Schnell) -

Trio

|

14' 32" |

|

CD 4 |

| -

4. Finale: Adagio - Allegro moderato |

26' 10" |

|

CD 4 |

| -

Applause |

0' 43" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 6 in A major - Original

Version |

|

65' 48" |

CD 5 |

| -

Applause |

0' 51" |

|

|

| -

1. Majestoso |

17' 02" |

|

|

| -

2. Adagio: Sehr feierlich |

22' 01" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo: Nicht schnell - Trio:

Langsam |

8' 18" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu

schnell |

15' 07" |

|

|

| -

Applause |

1' 00" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 7 in E major - ed.

Nowak |

|

81' 27" |

|

| -

Applause |

0' 50" |

|

CD 6 |

| -

1. Allegro moderato |

24' 16" |

|

CD 6 |

| -

2. Adagio: Sehr feierlich und sehr

langsam |

28' 46" |

|

CD 6 |

| -

3. Scherzo: Sehr schnell - Trio:

Etwas langsamer |

11' 35" |

|

CD 7 |

| -

4. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu

schnell |

14' 31" |

|

CD 7 |

| -

Applause |

0' 58" |

|

CD 7 |

|

|

|

|

Te

Deum - 1883/84, ed. Peters

|

|

31' 59" |

CD 7 |

-

Te Deum: Allegro moderato

|

9' 41" |

|

|

-

Te ergo: Moderato

|

3' 33" |

|

|

-

Aetrrna fac: Allegro moderato

|

2' 16" |

|

|

| -

Salvum fac: Moderato - Allegro

moderato |

9' 02" |

|

|

| -

In te, Domine, speravi: Mäßig bewegt

- Allegro moderato - Alla breve |

7' 27" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

No. 8 in C minor - 1890,

ed. Nowak

|

|

105' 10" |

|

| -

Applause |

0' 57" |

|

CD 8 |

-

1. Allegro moderato

|

20' 56" |

|

CD 8 |

-

2. Scherzo: Allegro moderato - Trio:

Langsam

|

16' 05" |

|

CD 8 |

| -

3. Adagio: Feierlich langsam, doch

nicht schleppend |

35' 04" |

|

CD 9 |

| -

4. Finale: Feierlich, nicht schnell |

32' 08" |

|

CD 9 |

| -

Applause |

0' 57" |

|

CD 9 |

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 9 in D minor

- ed. Nowak |

|

75' 50" |

|

| -

Applause |

0' 57" |

|

CD 10 |

| -

1. Feierlich. Misterioso |

32' 26" |

|

CD 10 |

| -

2. Scherzo: Bewegt, lebhaft - Trio:

schnell |

13' 47" |

|

CD 10 |

| -

3. Adagio: Langsam, feierlich |

30' 37" |

|

CD 11 |

| -

Applause |

1' 04"

|

|

CD 11 |

Excerpts

from the rehearsals (3-11)

|

|

32' 43" |

CD 11 |

|

|

|

|

| Mass

No. 3 in F minor |

|

77' 16"

|

CD 12 |

| -

1. Kyrie: Moderato |

12' 28"

|

|

|

| -

2. Gloria: Allegro - Andante, mehr

Adagio (sehr langsam) - Tempo I -

Ziemlich langsam |

15' 00"

|

|

|

| -

3. Credo: Allegro - Moderato

misterioso - Langsam - Largo -

Allegro - Tempo I - Moderato -

Allegro - Etwas langsamer als

anfangs - Allegro |

24' 13"

|

|

|

| -

4. Sanctus: Moderato - Allegro |

2' 38"

|

|

|

| -

5. Benedictus: Allegro moderato -

Allegro |

11' 29"

|

|

|

| -

6. Agnus Dei: Andante - Moderato |

10' 45"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Te

Deum |

Mass

No. 3

|

Münchner

Philharmoniker |

|

|

|

Sergiu

CELIBIDACHE |

|

| Margaret Price,

soprano |

Margaret Price,

soprano |

|

|

| Christel Borchers,

contralto |

Doris Soffel,

alto |

|

|

| Claes H. Ahnsjö,

tenor |

Peter Straka,

tenor |

|

|

| Karl Helm, bass |

Matthias Hölle,

bass |

|

|

| Philharmonischer

Chor München |

Philharmonischer

Chor München

|

|

|

| Members of the

Munchen Bach-Chor |

Josef Schmidthuber,

chorus master |

|

|

| Josef Schmidthuber,

chorus master |

|

|

|

| Elmar Schloter,

organ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Philharmonie

am Gasteig, München (Germania):

- 19 & 20 marzo 1987 (Symphony

No. 3)

- 16 ottobre 1988 (Symphony No. 4)

- 14 & 16 febbraio 1993

(Symphony No. 5)

- 29 novembre 1991 (Symphony No.

6)

- 10 settembre 1994 (Symphony No.

7)

- 12 & 13 settembre 1993

(Symphony No. 8)

- 10 settembre 1995 (Symphony No.

9) & 4-7 settembre 1995

(Excerpts)

- 6 & 9 marzo 1990 (Mass No.

3)

Lukaskirche, Mariannenplatz,

München (Germania):

- 1 luglio 1982 (Te Deum)

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recordings

|

|

|

Recording

engineers |

|

Torsten

Schreier, Gerhard von

Knobelsdorff, Lydia Schön (No. 3)

Michael Kempff & Wolfgang

Karreth (Nos. 4, 5)

Gerald Junge (Nos. 6, 7, 8, 9)

Michael Kempff & Wilfried

Hauer (Te Deum)

Hervé Poissonnier (Excerpts No. 9)

Torsten Schreier & Gunter Heß

(Mass No. 3)

|

|

|

Prime Edizioni CD |

|

EMI

Classics - 5 56689 2 - (1 CD) -

durata 66' 42" - (p) 1998 - ADD -

(No. 3)

EMI Classics - 5 56690 2 - (1 CD)

- durata 79' 11" - (p) 1998 - ADD

- (No. 4)

EMI Classics - 5 56691 2 - (2

CD's) - durata 48' 03" & 41'

50" - (p) 1998 - DDD - (No. 5)

EMI Classics - 5 56694 2 - (1 CD)

- durata 65' 46" - (p) 1998 - DDD

- (No. 6)

EMI Classics - 5 56695 2 - (2

CD's) - durata 54' 24" & 60'

00" - (p) 1998 - DDD (No. 7) - ADD

(Te Deum)

EMI Classics - 5 56696 2 - (2

CD's) - durata 38' 35" & 68'

53" - (p) 1998 - DDD - (No. 8)

EMI Classics - 5 56699 2 - (2

CD's) - durata 47' 39" & 65'

40" - (p) 1998 - DDD - (No. 9

& Excerpts)

EMI Classics - 5 56702 2 - (1 CD)

- durata 77' 16" - (p) 1998 - DDD

- (Mass No. 3)

|

|

|

CD Coffret

|

|

EMI

Classics - 0 85578 2 - (12 CD's) -

(c) 2011 - ADD/DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

This

recordings has been processed

using Spectral Design AudioCube

technology.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As Time Goes

By, or "The Case of

Sergiu Celibidache"

‘The

appearance is not

dissociated by the

observer but rather

swallowed up and entangled

with his own

individuality' (Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe)

He was

said to be difficult, a

non-conformist, one ‘whose

radicality was polarizing...

creating either respect and

admiration or mistrust and

rejection’, a man who caused

distress and wore people

down, and who issued a

legendary, strict

repudiation of any form of

recording. (The few

exceptions from his early

years as well as the studio

performance of his own

composition Der

Taschengarten that he

conducted as a benefit for

UNICEF are not under

consideration here.)

Ultimately, they served only

to increase his own value as

a rarity on international

concert platforms, a more or

less enigmatic oddity of the

music scene, to whose

successive places of

activity only his most

devoted followers flocked.

Thus was Sergiu Celibidache

presented to outsiders over

the course of decades. The

most knowledgeable of

critics were at loggerheads

over his controversially

slow tempos, which one

faction perceived as

plumbing unprecedented

depths, and the opposition,

perceiving a desecration of

their household gods, worked

themselves up to scurrilous

utterances, while a third,

somewhat neutral, camp, was

savouring the hullabaloo

indulged in by their

otherwise respected

colleagues. All the while

there sat the object of the

controversy himself,

relishing it and happily

fuelling the fire.

It is as though all these

critics had picked out

particular aspects of the

universe created by

Celibidache in line with

their own discretion, taste

and motives, and in doing so

produced a puzzle whose

pieces, once removed from

the whole picture, became

clichés that no longer

fitted together. This was

already the situation

prevailing on 14 August 1996

when the heart of the

‘controversial`, ‘different’

maestro stopped beating in

the hospital at Nemours. At

his home in La

Neuville-sur-Essonne,

southwest of the forest of

Fontainebleau, he had been

in the midst of preparing

his next musical projects

for Munich’s Gasteig

Philharmonie, his artistic

residence of long standing.

The heart attack could not

really be called unexpected

- some years earlier he had

had a pacemaker implanted as

a precautionary measure -

and yet it came as a

surprise: here was someone

who dealt as

self-confidently with the

phenomenon of time as

anyone, who exuded an aura

of immortality even when

physical symptoms told a

different story. The notion

that ‘one day he would no

longer be there’ never

crossed anyones mind.

Writing now just before the

15th anniversary of

Celibidache's death, the

situation has altered

fundamentally. Appearances,

as our privy councillor

Goethe rightly concluded,

are not dissociated from us

observers. And if we want to

comprehend them we must not

lose our way in

two-dimensional

reproductions, received

prejudices or others'

judgments, which only serve

to increase our own

inability to see clearly.

The honourable assignment of

writing a new introduction

to the present edition has

had to be approached

subjectively, resisting the

temptation to dig out the

old ‘clichés’ and

‘swallowing up and

entangling’ the phenomenon

of Sergiu Celibidache with

one's own individuality -

not so much for those who

have already travelled along

the path as for all those

curious individuals who may

be as bemused by the

external appearances as

Atreyu, the hero of

Fantastica in Michael Ende’s

Neverending Story,

when confronted with the

No-Key Gate, which opens

only to those who approach

it without any intention of

entering.

Space

Fulfilled by Time - The

Cosmos of Anton Bruckner

...

a feeling for the truth

and the ability to

understand it are present

in every human being. (Rudolf

Steiner)

When,

after two and a half decades

of professional wanderings,

Sergiu Celibidache arrived

at his last and longest

music directorship, in 1979

in Munich, he immediately

surprised his new orchestra

with an unforeseeable

innovation: ‘He assiduously

saw to it that the sections

sat as closely together as

practicable in order for

them to hear one another as

well as possible. Then he

had the experienced

professionals tune section

by section, first basses and

cellos, then the violins and

finally the violas, after

the customary free-for-all

had elicited his comment:

“The best way not to tune!"

How could that not be taken

as a form of humiliation?’

This account- which comes

from Harald Eggebrechts 1992

illustrated book Sergiu

Celibidache and is

headed ‘Nur der Freie kann

Musik machen’ (‘Only the

free person can make music’)

- characterizes the ensuing

17 years of rehearsals and

concerts under the merciless

direction of the man with

the lion’s mane. After three

days, Celibidache’s

conviction, ‘In the

beginning lies the end’, was

almost fulfilled in a manner

that might be described as

‘human, all-too human`:

"Celi" interrupts work on

Richard Strauss's Death

and Transfiguration

because he detects muttering

in the brass. Upon further

questioning, he is informed:

'This passage has been

played differently in the

past.'

What happened next has been

so thoroughly documented in

the press that we prefer to

spread a cloak of silence

and leave the reader to

imagine the excruciatingly

embarrassing, thundering

theatrics, the dramatic

debates and grovelling

attempts at placation - or

else to skip ahead to the

eye of the storm: all that

ranting and raving, storm

clouds and lightning, the

wild, fierce glances and

words, the seemingly endless

repetitions and polishing

were not part of some

large-scale harassment, as

the defenders of democratic

artistic practice or

anti-authoritarian training

methods suspected. No, they

were the mimed, verbal and

intellectual axe-blows of a

galvanizing figure who

sought to manoeuvre all

those involved in his

music-making - including

concert audiences and

attendees of his almost

always open rehearsals -

away from encrusted habits

and mechanical routine and

to take them along ‘to the

other side’, where kindred

spirits rub shoulders and

where, as Ferruccio Busoni

so indelibly formulated at

the end of his New

Aesthetic, there is

only music sounding - not

the strains of musical art.

The few rehearsal excerpts

included on CD 11 following

the Adagio from Anton

Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony

serve as a passing

confirmation of the

preceding descriptions. They

belong to the performance of

that work that took place in

the Munich Philharmonie on

10 September 1995, less than

a year before "Celi" passed

away - an 83-year-old who,

after a lifetime with

Bruckner, could still

express childlike wonder:

‘Where else do you find

something like this? The way

it’s put together in

harmonic terms alone -

unbelievable!’ (Scherzo

[6]). Invoking the biblical

phrase ‘Seek and ye shall

find’ as the strings bungle

the Start of the slow final

movement [7], he then keeps

working on the first

eruption until everyone is

hearing each other again:

‘You're making noise, not

music. Didn’t you hear the

trumpet part? What notes

were they playing, the

trumpets? Of no interest to

us. They don’t belong to us’

[7] (beginning c. 9.00).

‘Where is the human

being? Those are just

notes!’ [8]. And finally:

‘Ladies and gentlemen, no

orchestra I know can do what

you’re doing! No other

orchestra could play like

that. In the most terrible fortissimo

an absolutely appropriate

transparency! One can hear

absolutely every part.

However, it’s a somewhat

different story with the

audience, and therefore I

recommend that you react to

what you hear and not to

what you know... With a full

house it’s different, and

the main thing is that you

should recognize the

functions that we’ve

established in this

rehearsal. At this point I

accompany horns and

transition them to the viola

- that’s something you need

to know. And when you work

with that in mind, things

can absolutely never turn

dark. - It’s a special joy

for me to conduct all of

you. I continue to be

astonished at how you keep

summoning up the capacity to

be stimulated; it's already

the fourth rehearsal and

we're playing on the same

level and with the same

intensity. Extraordinary!

When I look back on my life,

we did Bruckner in Berlin

and I conducted his music

throughout my entire career

- I cannot recall a

performance in which

everything came together the

way it has happened with

you. Whether pro-Celibidache

or anti-Celibidache,

everyone is playing with

their whole heart. That is

so rewarding! I still

believe that it’s a

gift from providence to have

lived in the period when

Bruckner was still being

discovered.' [11]

· · · · ·

With

his phenomenal memory,

razor-sharp hearing and

pianistic facility, Sergiu

Celibidache must have

dumbfounded many observers,

including, on one occasion,

five musicians who had just

tackled Arnold Schoenberg's

Wind Quintet Op.26. Not only

did he proceed to play them

the whole score from memory

at the piano; he also reeled

off all the inaccuracies in

their rendition. This

capacity for sponge-like

absorption by no means

interfered with his ability

to learn: ‘Herr Doctor, how

fast does that go?’ he once

asked Wilhelm Furtwängler

about a particular passage.

The answer had unexpected

consequences: 'Ah, that

depends on how it sounds.'

Later, Celibidache alluded

to this laconic remark: ‘So,

the way it sounds can

determine the tempo! Tempo

isn’t a reality per se, but

a condition. If there are an

enormous variety of factors

working together, then I

need more time in order to

create something musical; if

less is going on, I can move

through more quickly.'

This explanation must have

been branded into him in red

letters, much to the

displeasure of those who

railed over his ‘famous slow

tempi' or, like the present

writer, who until recently

turned away in indifference.

And with Anton Bruckner, of

all composers! I can still

hear myself saying: ‘I can

live without a 90-minute

Eighth!’ That may well be

true when I’m sitting in

front of my speakers and

listening to a studio

production, whose panorama,

definition and tonal

character are determined by

the recording space as well

as by my own playback

conditions. There it is

possible to rein in

effectively the massive

dimensions of a not exactly

dainty score. And that's why

I reject the idea of

‘unnecessary’ duration - if

only there weren’t this

strange pull, which seems to

follow from a ‘feeling for

the truth’: could all the

applause showered on

Celibidache and his Munich

orchestra have been only

sound and fury - an audible

receipt for a monetary

outlay which demanded

approbation? Applause of

that sort sounds different,

and music that is rolled out

only for the sake of being

original or even didactic

(‘Beethoven’s metronome was

broken') cannot cast such a

spell.

As an experiment, I expand

the parameters of my concept

and suddenly ask myself:

‘Slow in relation to what?`

(Only later did I discover

that "Celi" asks exactly the

same thing in rehearsals for

the Ninth.) Slow in relation

to the stopwatch with which

some critics arm themselves

in order to be able to file

an ‘objective` report? In

relation to the parking

ticket that has been placed

behind the windscreen for

the traffic warden but will

expire long before the

concert ends? Is the

babysitter sitting on pins

and needles because he or

she has an exam tomorrow? Do

we bring nothing to the

occasion but our previous

listening experiences

(‘We've heard this passage

played

differently in the past’)?

Something from the outside

always impinges. And yet:

‘When you go to a concert

you must leave everything at

home and hope. And then

listen. You will discover

that things develop - or

don’t. If they develop, you

are free. If you force them

to develop, what develops is

neither free nor does it

come from within you. That’s

hard for Europeans to

understand. But music is

nothing else.' And: ‘If you

have the feeling it’s too

long or too short, you’re

already on the outside.

Music doesn’t last in that

sense’ (Celibidache). This

doesn’t mean we have to

squat in lotus position or

mumble incantatory

syllables. We aren’t even

obliged to believe the wise

words of others with rolled

eyes simply because they've

been hailed as wise. But

when the great architectural

structures breathe, when the

blossoms open and close,

when the space is saturated

with 'fulfilled' time that

abolishes itself and, in the

final eruption of the Ninth,

even approaches Alexander

Skryabin’s 'Universe' - then

the moment meets eternity:

in the beginning is the end

is the beginning...

Eckhardt

van den Hoogen

(Translation:

Richard Evidon)

|

|

|

|