|

|

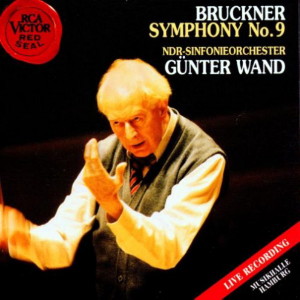

1 CD -

09026 62650 2 - (p) 1994

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

No. 9 in D minor - Originalfassung

(1887-94)

|

|

65'

07"

|

|

| -

1. Feierlich, misterioso |

26' 55" |

|

|

| -

2. Scherzo. Bewegt, lebhaft - Trio.

Schnell |

10' 43" |

|

|

| -

3. Adagio. Langsam, feierlich |

26' 52" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NDR-Sinfonieorchester |

|

| Günter WAND |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Musikhalle,

Hamburg (Germania) - 7-9 marzo

1993 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Recording

supervisor |

|

Gerald

Götze |

|

|

Balance engineer |

|

Karl-Otto

Bremer |

|

|

Editing |

|

Suse

Wöllmer, Sabine Kaufmann

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

SONY

[RCA VICTOR Red Seal] - 09026

62650 2 - (1 CD - 65' 07") - (p)

1994 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

A

Co-Production of Bertelsmann Music

Croup & Norddeutscher Rundfunk

Hamburg |

|

|

|

|

Bruckner’s

Ninth Symphony

Without

doubt the greatest and most

important composer of

symphonies in the second

half of the nineteenth

century, Anton Bruckner

holds a key role between

Beethoven, Schubert and

Mahler, and not just for the

Austrian musical tradition.

His significance reaches

further afield, both

historically and

geographically, although -

and perhaps precisely

because - his style is so

singular. It is only in the

second half of our century

that this is gradually

becoming clear, and a

performer as deeply in

sympathy with Bruckner's

works as Günter Wand makes a

contribution towards this

re-evaluation that can no

longer be ignored.

Bruckner was, with a very

few exceptions, simply not

understood in his own time.

Even friends and musical

sympathizers of this unique

man were unable to follow

him and out of pure goodwill

pressed Bruckner, who was

perpetually plagued by

feelings of inferiority, to

make constant revisions,

abridgements and to agree to

illconceived “improvements”

which he himself perpetrated

on his works. However,

Bruckner remained firm on

one point: the text which he

declared “valid” should be

handed on unaltered to

posterity, uninfluenced by

contemporary “good deeds”

such as cuts and changes in

instrumentation - and he did

indeed achieve this goal by

leaving fair copies of his

scores, dated and

meticulously marked without

ambiguity, and by making

equally unambiguous

provisions in his will for

their preservation.

It was the example of the

Ninth Symphony that gave an

astonished posterity its

first indication of the

extent to which the versions

of Bruckner's symphonies

performed even well into our

century were distorted.

(Even today there are said

to be conductors who prefer

the “more effective”

reworking to the original

version!) In a spectacular

concert which caused a

sensation in the musical

world on the 2nd April 1932

in Munich, Siegmund von

Hausegger performed

Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony

twice in succession: once in

the version known up to

then, the score of which had

been published in 1903 by

Ferdinand Löwe, and

afterwards according to the

text which was faithful to

Bruckner's autograph - in

other words, the original

version. The difference was

stunning, and it was clear

to every listener that this

work (and presumably, as was

later confirmed, also other

symphonies of Bruckner's)

had up to then never been

performed as the composer

himself had intended. Even

Löwe’s reworking, which does

not even identify itself as

such in the score of 1903 -

in spite of all the credit

this Bruckner pupil deserves

for performing the Ninth and

having it printed -

thoroughly distorts, indeed

falsifies the original

artistic intention. The

problem was first recognized

by Robert Haas, head of the

music department of the

Vienna National Library

(which as the successor of

the former Court Library had

custody of Bruckner’s

unpublished works) and later

biographer of Bruckner.

Studying the sources

carefully and comparing them

with the printed scores, he

discovered the discrepancies

and the substantive

differences and persuaded

the conductor von Hausegger

to carry out the Munich

experiment which produced

such powerful proof. Our

gratitude must go to Haas’

initiative for the first

critical edition of the

complete works based on

Bruckner’s original

manuscripts, being

undertaken in collaboration

with the International

Bruckner Society and the

Vienna National Library; as

well as Haas, the Bruckner

researchers Nowak, Oeser and

Orel took part in this first

complete edition, finished

in 1944. After the war the

International Bruckner

Society published a new

edition, which differs only

in insignificant points from

the basic findings of the

first edition of the

original text.

The main differences between

the original version and the

reworking are to be found on

the levels of form, sonority

and dynamics.

Small and larger cuts

destroyed the original form,

and instead of becoming

clearer and more obvious,

Bruckner’s monumental

architecture (based on the

most precise symmetry and

proportionality,

corresponding to his almost

manic preoccupation with

numbers was made to seem

more enigmatic. Similarly,

in most reworkings

Bruckner’s original

“terraced” dynamics, which

were inspired by the

dynamics of organ

registration and which make

sharp contrasts between

extremes of intensity, are

falsified by arbitrarily

introduced crescendos and

decrescendos. Sections

separated by general pauses

are often run together, and

tempo alterations are

introduced through

accelerandos and

ritardandos, as are other

melodic, harmonic and

rhythmic “improvements” -

all this, be it noted, done

with the best of intentions

and in many cases even with

the explicit or tacit

agreement of the composer,

who had a strong regard for

authority and little

experience of performance.

He once called the

conductors who brought his

work to performance with

such alterations his

“guardians appointed by

Wagner”, and he allowed

Felix Weingartner “only to

make heavy cuts; for it

would be too long and is

suitable only for a later

time”. And on another

occasion: “Please do only as

your orchestra requires; but

please do not alter the

score, and leave the

orchestra parts unchanged

when they are printed: that

is one of my most heartfelt

requests.”

Severe

interference also affected

the sonority, the

instrumentation. Bruckner,

in a way similar to his

treatment of dynamics,

develops the principle of

blocks differentiated by

sonority into a formal

structure of sound groups,

clearly separating the basic

colours of strings, woodwind

and brass; he uses mixtures

of these only within the

restrictions of his strict

formal principles. However,

in most of the scores

printed before the critical

edition, the predominant

ideal of those who reworked

the music was a mixing of

sound colours in the manner

of a Lisztian-Wagnerian

orchestral sonority.

To justify this, those who

reworked the scores were

able to point to Bruckner’s

idolatrous admiration for

Wagner: indeed, Bruckner

adopted from him and

developed further many bold

chromatic and enharmonic

details in the harmony which

were new and unheard of at

that time. However, in

orchestration, Bruckner, as

a symphonist worked out his

ideas of sonority from the

organ, and so deviated

considerably from the way in

which Wagner the

music-dramatist used

instrumentation.

This problem leads us

directly to that of

Bruckner’s unwilling

participation in the

argument between different

parties in Vienna: not

political parties, of

course, but factions in

conflict over aesthetic and

musical issues. By 1874 -

when he dedicated the Third

Symphony to Wagner (who

received the score and

merely sent his thanks by

way of Cosima) - if not

earlier, Bruckner had been

labelled a Wagnerian and

hence one of the progressive

party. The conservative

majority of the Viennese

musical world, whose

ideological leader was the

intellectual critic and art

theorist Hanslick, held fast

to the (possibly

misunderstood) ideal of

classicism and its formal

canon. This faction

considered Johannes Brahms,

who against his will thus

became the antithesis of

Bruckner, to be their

contemporary protagonist who

seemed to be continuing the

work of the three classical

titans. Nowadays it is

obvious that such

pigeon-holing does the later

Brahms, at least, a similar

wrong and an injustice

comparable in its flagrancy

to the injustice done to

Bruckner, who in the depths

of his soul was anything but

a revolutionary: he

inscribed all his music, as

the medieval masters or

Johann Sebastian Bach used

to do, “soli Deo gloria” -

to the glory of God alone.

He really had nothing in

common with the factions of

his time, and he suffered

unspeakably from their

effects on him, in

particular from the

intelligent and therefore

all the more hurtful attacks

of Hanslick. Against this

historical background

Bruckner’s incessant

striving for proof of

recognition becomes

understandable: for exams

and formal academic approval

even in old age, for a

university position, the

title of Doctor and a

professorship. The honours

and (meagre) demonstrations

of the emperors favour on

the whole came too late to

change or affect in any way

Bruckner’s simple life

style, which in modern eyes

would seem almost

impoverished, or at best

monkishly frugal. Until his

death he remained a great

loner, perhaps the greatest

in recent music history, and

his life’s work even

nowadays, almost a century

after his death, stands

before us isolated and

anomalous.

With the “restlessness of a

mighty mind” (Friedrich

Blume), Bruckner made from

one symphony to another

ever-renewed efforts, on an

ever-evolving level, to

solve the single problem

which hovered before him; to

summarize in the monumental

structure of large-scale

symphonic architecture the

totality of the

possibilities of form and

expression which his era

afforded, to God’s praise

alone and for His higher

honour. He wanted to elevate

and concentrate this

structure to reach the

supreme greatness and

sublimity which lay within

his grasp. Anton Bruckner’s

symphonic works are, among

other things, also a

monument to monistic

certainty of belief in a

secular and pluralistic

world, and thus the

conclusion of a whole epoch

of Western music history,

which derives the purpose

and justification for music

from its transcendence, from

its ability to reflect the

ethical (in the final

analysis God’s commandment)

in the aesthetic, realized

in artistic form. Each

individual symphony, and

none more than the Ninth, is

the reflection of one and

the same ideal type, uniting

elements of Gregorian chant

and Bachian linearity with

Beethoven’s powerful sense

of drama, Schubert’s

Romanticism placed in a new

formal setting and Wagner’s

chromatically expressive

harmony, to form an

unmistakably Brucknerian

synthesis. Bruckner’s Ninth

Symphony could also bear the

nickname “Unfinished”, for

in addition to the three

completed movements he left

181 pages of sketches with

more than 400 bars for a

final movement which he

obviously intended to

include, but which remained

unfinished. The earliest

dated sketch for the first

movement is from the 21st

September 1887. Bruckner

worked on this symphony

longer than on his earlier

works. The first movement

was finished on the 23rd

December 1893 and the

Scherzo was written between

January 1889 und February

1894. The Adagio, on the

other hand, was written in

it entirety in 1894. The

dates (beginning the 23rd

April and ending the 30th

November 1894) indicate that

Bruckner worked

uninterruptedly on this, his

last completed symphony

movement, whereas between

the original draft and the

completion of the first two

movements he had also been

busy with the revisions

ofthe Eighth and First

Symphonies. It is said that

he continued to work on the

Finale right up to his death

in October 1896, although

there are no dated documents

to prove this.

As Robert Haas writes, the

Ninth Symphony, Bruckner’s

farewell to life, “stands in

splendid isolation at the

end of the chain of

symphonies, with shudders of

eternity blowing round it...

The dedication to God

signifies both the summation

of his whole lifetime and

the fervent spiritual

submissiveness of this

confession of a lifetime.”

The first movement, with the

three groups of themes

typical of Bruckner, has

throughout - and not only in

the development section - a

belligerent, powerful,

severe and serious effect.

The coda intensifies one

component of the main

movement, turning it into a

deeply meaningful chorale

for brass.

In second place in this

symphony is a Scherzo,

which, as E. van den Hoogen

notes, “makes a mockery of

its name and allows no room

for the slightest gesture of

reconciliation”.

In these rugged contours,

one finds none of the

idiomatic sounds at home in

Upper Austria which are

occasionally found in other

Brucknerian scherzos: this

is particularly obvious in

the Trio. This is not

leisurely and Ländler-like,

as is usual in Bruckner;

rather, the tempo

accelerates further,

reinforcing the impression

of the movement's character

as a dance of death - a

highly original movement,

rhythmically, harmonically

and melodically almost

bizarre.

The ensuing Adagio extends

the symphony’s thematic

diversity, structural

dimensions and intensity of

sound-colours. In spite of -

and perhaps precisely

because of - its overall

character as a magnificent

swan-song, it penetrates

into new worlds. The main

theme touches all twelve

semitones of the chromatic

scale, and the downright

sinister climax of the

concentration of sound turns

into a dissonant chord which

piles up no less than seven

of the twelve semitones on

top of one another, just

before the beginning of the

blissful conclusion in E

major. Bruckner himself

called the tuba phrase in

the second theme his

“farewell to life”, and

Robert Haas, his biographer,

still writing under the

influence of Romanticism,

considers the entire final

movement “a celebration of

eternal desire” at the end

of which “the gates of

heaven open”, and he speaks

of the “relaxation of the

conclusion in the

inebriation of death".

Certainly the quiet

conclusion by the horns over

the pianissimo

chords of the tubas and

trombones and the pizzicatos

of the strings, calmly

swaying and undulating into

silence, is uniquely

beautiful - a final

swan-song in the true sense

of the word, which nothing

else can follow.

Altogether the three

finished movements of this

Ninth Symphony evidence an

unparalleled boldness,

spaciousness and uniqueness

of structural design. Their

architecture spans a broad

range, “like a gigantic

mountain landscape”

(Kloiber). In a radio

conversation with the author

of these lines, Günter Wand

once admitted “it took me a

very long time not just to

recognize the magnificent

arches of the architecture

of Bruckner`s works - even

that took me a long time -

but to achieve the necessary

calm to convey them in

performance. In Bruckner’s

work, in these gigantic

blocks from which the

architecture of his

symphonies is fashioned, the

thing that moves me e in (I

might almost say) an unreal

way - is something like the

reflection in the music of a

cosmic ordering, something

which I feel is not

measurable in human terms.

And I would love to try to

let this background to

Bruckner’s music, this

reflection of divine order,

become obvious, to make it

clear.”

Wolfgang

Seifert

(Translation: Byword,

London)

Some

Thoughts on

Bruckner’s Ninth

Symphony

Concern with

the primitive forces of

rhythm, the conflict of

odd and even in the

dimension of time, is a

characteristic of all

the symphonies of Anton

Bruckner. It plays an

important part in the

shaping of themes where

duplets and triplets

follow one another,

taking up an equal

length of time. It is

even more important in

the form of rhythmic

counterpoint, when

forces which by nature

repel one another are at

length compelled to

coexist in the same

period of time. This

rhythmic dualism is

quite peculiar to

Bruckner and it

represents a driving

force in the mighty beat

of his symphonic style,

coming from within and

setting all aglow. We

are dealing now with a

content which points far

beyond the techniques of

rhythm in music. This

dualism seems to have a

symbolic force, standing

for the irreconcilable

elements in human nature

and for the longing to

transcend them. It is

Bruckner’s firm grasp

upon the interdependency

of time and space which

forms the mortar binding

together the blocks of

primitive stone out of

which his symphonic

cathedrals are built.

The architecture of

Bruckner’s music is

different from that of

the classical symphony

in which the thematic

material underwent

development. In

Bruckner’s music it

means the confrontation

of thematic blocks and

the achievement of a

satisfying balance

between them, a balance

both in terms of

tone-colour and in terms

of the time-space

dimensions. The

confrontation of odd and

even rhythmic values and

the attempt to fuse

these together in the

same period of time can

lead to tremors and

eruptions which are

truly volcanic and,

indeed, seem not far

removed from cosmic

events. Sometimes note

values are doubled or

trebled as, for example,

when triplets in quavers

are transformed directly

into triplets in

crotchets and minims.

The effect of this is

not so much to slow down

the tempo as to increase

the feeling of space

(cf. the finale of the

Fourth Symphony).

There are passages in

Bruckner’s music where

the laws of tension and

relaxation seem no

longer to obtain.

Different rhythmic

impulses of a similar

quality are formed into

layers, some of which

then move at double the

pace of the others. A

strange phenomenon is

produced; the form has

musical motion, yet the

effect is static. It is

like viewing the stars

of the nightly

firmament, which take

their courses but seem

to stand still. It is

only for moments that

Bruckner’s music moves

into such dimensions.

The “development” in the

first movement of the

Ninth and the ppp

stretto in the fugal

finale of the Fifth are

examples.

In all this we do not

have the feeling that

such effects of rhythmic

energy are studied or

calculated - as if they

were a display of

particular subtlety on

the composer’s part.

(For that, we may look

to the oboe’s 4/4

departure from the

prevailing 6/ 8 metre of

Mozart’s Oboe Quartet.)

On the contrary, the

compelling power of

these inspired passages

in Bruckner seems formed

by nature and totally in

keeping with the natural

form and beauty of those

unique themes.

The Ninth is rougher in

sonority in comparison

with the earlier

symphonies and sometimes

it seems as if Bruckner

were consciously

dissociating himself

from them. It is due to

his completely

uncompromising treatment

of polyphony, something

which offends some ears

at first hearing. It

expresses renunciation

of the world and an

inner truthfulness

which, after so many

ecstatic visions of

glories beyond the

grave, is not afraid to

express the dissonances

of the deepest chasms.

This fearful cry, in

which man’s weeping for

paradise lost seems to

echo on to the end of

time, can find of its

own no solution, no

deliverance. Silence

follows. Then the step

is taken towards the

security of the faith.

The music seems to throw

off the bonds of matter,

and from now on until

the transfigured

conclusion the music

pulses in the certaintz

of the NON CONFUNDAR IN

AETERNUM.

Günter

Wand

|

|

|