|

|

1 LP -

2530 828 - (p) 1976

|

|

| 1 CD -

419 083-2 - (c) 1987 |

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphonie

Nr. 9 d-moll |

|

61' 04" |

|

| Versione

originale |

|

|

|

| -

1. Feierlich, misterioso |

24' 42" |

|

|

| -

2. Scherzo: Bewegt, lebhaft |

10' 36" |

|

|

| -

3. Adagio: Langsam, feierlich |

25' 46" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Berliner

Philharmoniker |

|

| Herbert von KARAJAN |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Philharmonie,

Berlino (Germania) - settembre

1979 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

studio |

|

|

Production |

|

Dr.

Hans Hirsch, Magdalene Padberg |

|

|

Recording

Supervision |

|

Michel

Glotz |

|

|

Balance Engineer |

|

GŁnter

Hermanns |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 2530 828 - (1 LP) -

durata 61' 04" - (p) 1976 -

Analogico |

|

|

Prima Edizione CD |

|

Deutsche

Grammophon - 419 083-2 - (1 CD) -

durata 61' 04" - (c) 1987 - ADD |

|

|

Note |

|

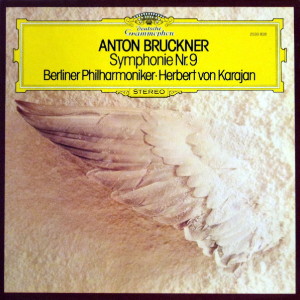

Cover

Design: Holger Matthies, Hamburg

|

|

|

|

|

In his essay

"The Symphony from Beethoven

to Mahler", which appeared

in 1918, Paul Bekker

distinguished between German

and Austrian symphonic

writing of the 19th century.

He attributed an

intellectual character to

German, but not to Austrian

symphonies, considering the

latter to be products of

undiluted romanticism, with

no intellectual basis.

Bekker's principal

conclusion in this respect

was that Austrian symphonic

music is a product of

romanticism entirely of the

senses, since all the ideas

clamouring to be expressed

are transformed into music

without any detour by way of

literary or programmatic

functions. He concluded, in

this connection, that

Bruckner carried on the

musical line of Schubert.

Anton Bruckner was certainly

not a composer of literary

orientation like Schumann,

or even Brahms.

Nevertheless, his sensuous

romanticism had motivation

of its own. In his Ninth

Symphony, he went further in

opening up hitherto

unexplored territory than in

any of his earlier works. It

cannot have been an urge for

novelty as an end in itself

which drove him in this

direction, but an elemental

creative wull beyond the

sphere of his senses,

influenced by metaphysical

concepts of existence. One

aspect of this work which

brings Bruckner close to

Schubert is its

incompleteness; like several

of Schubert's sonatas,

Bruckner's D minor Symphony

has no finale - it ends with

an Adagio. This

incompleteness - though it

was not Bruckner's intention

- leaves the listener with a

sense of nearness to death

and transcendence.

What may be experienced in

late Schubert (and

throughout Wagner) as a

longing for death appears in

Bruckner's Ninth Symphony as

preparedness for death - not

as a fatalistic insight into

what cannot be avoided.

Here, Bruckner stands before

us as a positive figure: a

devout man determined to

fight. The character of the

music, programmatic in the

wider sense, does away with

rigid boundaries between

component parts of the

structure, allowing for the

creation of freer formal

blocks which influence one

another, their inner

development clearly

resulting from the specific

characteristics of their

subject matter.

In the first movement,

Bruckner works with three

main themes and motive

material derived from them,

making use of only a very

free concept of sonata form.

The Scherzo is dominated by

diffuseness of the sound

picture, the scene being set

immediately by a dissonant

chord played by an oboe and

three clarinets. The key of

D minor is clearly

established only in the

enthralling string passage

to a stamping three-four

rhythm (bar 42), and even

then the tonality is quickly

obscured by harshly

conflicting dissonances. The

sense of anxiety and

disquiet engendered by this

movement is not dispelled by

its Trio in F sharp major,

and indeed becomes still

more pronounced as fleeting

wisps of sound and jagged

figures create in icy

atmosphere. In the Adagio,

Bruckner opens up broad

tonal expanses. Never before

did he so plunge into

apparent unreality - the

opening theme's initial leap

of a ninth at first gives no

clear indication of its key

centre. As the movement

proceeds, the

transfiguration of the

musical material is carried

to its conclusion. The

correctness of Bekker's

assertion is, however,

confirmed: here, without any

intellectual preconception,

Bruckner has entered into a

hitherto unknown area of

experience, with the aid of

his unshaken, unadulterated

romanticism.

Hanspeter

Krellmann

(Translation:

John Coombs)

|

|

|