|

|

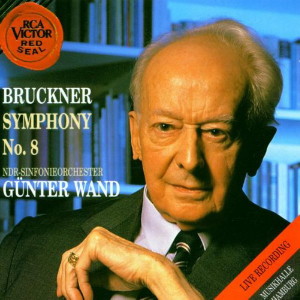

2 CD's

- 09026 68047 2 - (p) 1995

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 8 in C minor

- 1884-90 Originalfassung

herausgegeben von Robert Haas |

|

87' 52" |

|

-

1. Allegro moderato

|

17' 16" |

|

CD 1 |

| -

2. Scherzo. Allegro moderato |

16' 05" |

|

CD 1 |

| -

3. Adagio. Feierlich langsam, doch

nicht schleppend |

28' 45" |

|

CD 2 |

| -

4. Finale. Feierlich, nicht schnell |

25' 46" |

|

CD 2 |

|

|

|

|

| NDR-Sinfonieorchester |

|

| Günter WAND |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Musikhalle,

Hamburg (Germania) - 5-7 dicembre

1993 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Recording

supervision |

|

Gerald

Götze |

|

|

Balance engineer |

|

Karl-Otto

Bremer |

|

|

Editing |

|

Suse

Wöllmer, Sabine Kaufmann, Antje

Maibom |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

SONY

(RCA VICTOR Red Seal) - 09026

68047 2 - (2 CD's - 33' 21" &

54' 31") - (p) 1995 - DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

A

Co-Produktion of Bertelsmann Music

Group & Norddeutscher Rundfunk

Hamburg |

|

|

|

|

|

Anton

Bruckner: Symphony no. 8

in C minor

In the

music ofthe latter part of

the 19th century, Anton

Bruckner occupies a position

of almost overwhelming

significance. Even today,

nearly 100 years after his

death, his works frequently

seem strange and erratic -

to music scholars no less

than to the concert-goer.

Bruckner is a solitary

figure, perhaps the most

solitary of all modern

composers. And yet he is of

key importance for the

development of Austrian

music between Beethoven and

Schubert on the one hand and

Gustav Mahler on the other.

Nor is Bruckner’s importance

confined to a 19th century,

Austrian context: his music

has far wider repercussions,

both historically and

geographically, although -

and perhaps precisely

because - his style is so

singular. Only today are

people gradually becoming

aware of Bruckner’s true

status. And a conductor like

Günter Wand, who is one of

the few interpreters

equipped to respond to the

challenge that Bruckner

poses, has made an

indispensable contribution

to a better understanding of

this great composer.

Bruckner’s contemporaries

were unable to grasp the

extent of his originality

and modernity. With only a

handful of exceptions, even

his friends and fellow

musicians could not follow

the artistic path chosen by

this unique man. Thus it was

out of sheer goodwill that

they compelled the composer,

who was constantly tormented

by feelings of inadequacy,

to make revisions and cuts

in his works, and even to

agree to "improvements" from

his own pen. Endowed with a

deep respect for authority,

Bruckner once called those

conductors who believed

themselves

capable of performing his

symphonies with so many

alterations as his

"guardians appointed by

Wagner". As long as he

lived, Bruckner suffered

from low selfesteem, and it

was easy to make him unsure

of himself: but when it came

down to it, he knew exactly

what he wanted, and adhered

in principle to the versions

of the scores that he had

declared to be “valid”. Thus

he did allow the conductor

“to proceed only as your

orchestra demands“, but

added: “please do not alter

the score, and when the work

is printed, one of my most

ardent wishes is that the

orchestration should on no

account be changed”. He went

to considerable lengths to

pass on his scores to

posterity in their original

form, free of alterations

and of cuts and changes in

the instrumentation carried

out by well-meaning

contemporaries. And in this

endeavour Bruckner was

successful: he wrote out

precisely dated fair copies

with meticulous attention to

clarity and detail, and left

these in his will to the

Vienna National Library,

where the autograph

manuscripts are kept to this

day. The later director of

the music library, the

Bruckner scholar Robert

Haas, made a careful

comparison of all the

original scores, and

prepared the first complete

Bruckner edition free of

‘foreign ingredients’, which

was then published between

1932 and 1944.

The contemporary

arrangements of Bruckner's

symphonies made alterations

to the form, the dynamics

and the actual sound. Cuts

small and large, supposedly

made in the interests of

comprehensibility, destroyed

the original form,

disguising the proportions,

the symmetry and the

parallels of the large-scale

designs so important to

Bruckner. The well-meaning

arrangers replaced the

layered, "terrace" dynamics

that Bruckner derived from

organ registration with

arbitrary crescendi

and decrescendi. In

many places, they also cut

the general rests so

important for an

understanding of the form,

and added tempo

modifications, accelerandi

and ritardandi of

their own, as well as other

melodic, harmonic and

rhythmic "improvements".

These activities shouldn't

be judged too harshly: we

must bear in mind that such

alterations were made with

the best intent, and in many

cases with the more or less

‘voluntary’ agreement of the

composer.

The most drastic alterations

were those that changed the

actual sound of the music.

Bruckner created an

architecture of sound

groups, along the same lines

as his terrace dynamics

reminiscent of organ music:

he combined blocks of

different sounds to form

groups, based on a clear

separation of the basic

timbres

(strings/woodwind/brass),

which were then reunited

according to strict formal

principles. Thus he created

a highly original sound

structure that is an

integral part of the

composition, and makes a

central contribution to our

formal understanding of the

large-scale movements of his

symphonies.

Bruckner’s arrangers,

however, most of them

distinguished conductors of

Wagner to a greater or

lesser degree, all swore by

a mixture of timbres in the

spirit of the orchestral

treatment practised by the

Liszt/Wagner school.

Needless to say, they were

convinced that their

re-orchestration of

Bruckner`s music was an

improvement on the original,

and that they were thus

making it easier for the

public to approach these

difficult works. As for

Bruckner's say in the

matter, the composers

idolization of Wagner meant

that the arrangers could

count on his approval of

their modifications.

It’s certainly true that

after attending performances

of Tannhäuser and Tristan

und Isolde in 1864/65

(it was at the premiüre of

the latter work in Munich

that Bruckner first met

Wagner), Bruckner adopted

many of the new and bold

harmonic details he found in

Wagner’s music, particularly

the prominent chromatics and

enharmonics. But as regards

orchestration, Bruckner

followed his own laws and

ideas of the sound he wanted

in his symphonies - ideas

taken from organ music, and

directed at a clear

separation of the different

registers rather than at the

seductive, magical sound-mix

that Wagner strove for.

Here, he trod quite

different paths from those

of the Bayreuth master he so

admired.

This, however, is something

Bruckner`s contemporaries

chose to ignore: after the

dedication of his Third

Symphony, he was regarded as

a Wagnerian composer. Even

as experienced a listener as

the Austrian critic Eduard

Hanslick only heard the

similarities, and not the

huge differences: he branded

Bruckner a “New German

revolutionary” whose aim it

was to transfer the endless

melody of opera to the

symphony, thus destroying

the Classical tradition that

found its culmination in the

music of Brahms. This led

Hanslick to attack Bruckner

as vehemently as he had

championed him prior to his

fall from grace: “We

encounter Wagnerian

orchestral effects wherever

we look. Bruckner’s new

Symphony in C minor is

characterized by the direct

juxtaposition of dry

counterpoint and boundless

gushing . . . Everything is

forced into one

unstructured, chaotic flow

of appalling length . . . It

is not altogether impossible

that this style - the

confused product of a

thoroughly depressed mind -

may represent the musical

future. If it does, then

future generations are not

to be envied ...” (Review of

the première in the Wiener

Zeitung, 1892.) Pure

prejudice obviously

prevented the aesthete

Hanslick, who proclaimed

music to be “moving form in

sound”, from seeing that the

strict formalist and

perfectionist Bruckner did

in fact embody this

principle - albeit in his

own, highly individual way -

with at least as much purity

as Hanslick’s idol Johannes

Brahms.

Anton Bruckner, who suffered

dreadfully from the polemic

that the ‘Brahmsians’ flung

in his direction, actually

had little to do with the

warring musical factions of

the time. He wrote all his

compositions - not only

those expressly dedicated to

"Our dear Lord" - for the

honour and glory of God

alone, soli deo gloria, as

did the medieval composers

and Johann Sebastian Bach

before him. He composed as

best he could, and if the

result did not meet his

exacting standards, then he

took no pity on himself,

declaring it to be ‘invalid’

and beginning work undaunted

on a second or even a third

version. It`s fair to say

that no other 19th century

composer spent as much time

revising his work as

Bruckner, putting as much

energy into this as into he

would into a completely new

composition. The background

to the Eighth Symphony

shows that this is certainly

one reason why Bruckner

never managed to finish the

Ninth.

Notwithstanding a nature in

some respects quite complex,

Anton Bruckner was basically

a simple man from a rural

background, and was deeply

religious. Without his

Christian faith, he probably

wouldn’t have survived the

many humiliations,

misunderstandings and

attacks he was subjected to.

Nevertheless, throughout his

life he suffered from

recurring depression and

lack of self-esteem, against

which he tried to defend

himself by gathering signs

of official recognition.

This may well explain the

incessant striving of the

former village schoolmaster

for more and more exams,

official positions and

honours, likewise the great

pride he took in his title

of professor, his university

post and his doctorate. But

all the public recognition

and the marks of the

Emperor’s favour came too

late to make any real

difference to Bruckner's

simple way of life, which

would seem almost wretched

by today’s standards, and

was nothing if not ascetic,

almost monastic in

character.

Although the insecurity in

his psychological make-up

meant that he was easy to

irritate, at the core of his

artistic being Anton

Bruckner could not be

influenced by others. All

his life, he continued

single-mindedly along the

path he had set out on, even

though the price he had to

pay for the privelege was

high. For he never lived to

hear even one of his

symphonies performed as he

had composed it, and as for

the Fifth, the Sixth

and the three completed

movements of the Ninth,

he never heard these

performed at all.

With the “restlessness of a

powerful mind” (Friedrich

Blume), Bruckner endeavoured

time after time, from

symphony to symphony, to

solve the one central

problem he faced. Within the

monumental edifice of

large-scale symphonic

architecture, he sought to

bring together all the

creative and expressive

possibilities that the

orchestral composition of

his time offered,

heightening and intensifying

them to achieve the utmost

possible grandeur and

sublimity for the sole

honour and greater glory of

Our Lord.

The sociologically-minded

may tend to view Anton

Bruckner's monumental

symphonies as a musical

expression of the years

after 1871, when Germany

experienced a period of

strong economic and

industrial expansion. This,

however, does nothing to

explain their unique

individuality. But if one

understands the Bruckner

symphonies first and

foremost as a monument of

monistic faith in an

increasingly secular and

pluralistic world, one comes

as close to their "content"

as is possible with absolute

music. It is the conclusion

of a whole era of Western

musical history which

derived the purpose and

legitmacy of its music from

its transcendence, from its

ability to reflect ethics in

aesthetics, i.e. in works of

art. (The ethical values

being taken, in the final

instance, from commandments

of God himself.) Each of the

symphonies, and the mighty Eighth

Symphony in

particular, is a reflection

of the same ideal, combining

elements of Gregorian

chorale and the linearity of

Bach with the strictly

formal dramatics of

Beethoven, Schubert’s

reoriented Romanticism and

Wagnerian harmonics, full of

chromatic expression, to

form an utterly distinctive

Brucknerian synthesis.

··········

Bruckner

began work on the Eighth

Symphony, his third in

the key of C minor, in

1884/85. He completed a

first revision in 1887 and

sent it to Hermann Levi,

chief conductor of the

Munich Opera. But Levi would

not accept this version of

the score for performance,

unlike the Seventh.

Bruckner was initially

thrown into depression by

the distinguished

conductor's somewhat

helpless rejection of a

score that was evidently too

much for him. But then he

began to feel more and more

inspired by the task facing

him, and in the next three

years, instead of

"simplifying" the symphony

as Levi wished, Bruckner

created a much more complex

new version of the work,

richer than its predecessor

both in terms of structure

and instrumentation.

However, in order that the

symphony could finally be

performed, Bruckner allowed

wellmeaning friends and

pupils, particularly the

conductor Franz Schalk, to

persuade him to make changes

and cuts (mainly in the

Adagio and the Finale) “to

facilitate comprehension of

the music”, even though they

clearly go against the logic

of the composition. With

these alterations

incorporated, the symphony

dedicated “in the deepest

respect” to the Emperor in

1890 was published the

following year by Haslinger

in Vienna and by Schlesinger

in Berlin: the printing

costs were paid by the court

in both cases. After its

première in this form in

1892, with Hans Richter

conducting the Vienna

Philharmonic, the work

turned into a painfully late

triumph for Bruckner, not

least through many repeat

performances in other music

centres.

As the aforegoing should

make clear, we have not one

but two ‘original’ versions

of the Eighth Symphony,

both of them preserved in

the autograph manuscript,

and both of them - as

biographical and especially

structural evidence within

the work shows - not

actually reflecting the

composer’s own intentions.

The second version is

indisputably superior to the

first as a composition, but

Bruckner”s intentions here

were distorted by the

‘disimprovements’ sketched

above. In 1939, Robert Haas

solved the dilemma with the

publication of the Urtext

in his complete critical

edition of the Bruckner

symphonies: in principle, he

based his score on the

second, extended and revised

version completed by the

composer in 1890, but he

went back to the autograph

of the first version that

Bruckner finished in 1887 in

order to replace the

material that was

irresponsibly cut out again,

destroying the form of the

work, and in order to remove

all other evidence of

outside interference. The

result could not be farther

from a ‘patch-up job’: it is

a musically convincing

organic whole. This Haas

edition of the Urtext,

volume 8 of the Critical

Bruckner Edition published

by the

Musikwissenschaftlicher

Verlag, Leipzig, was used as

the basis for this live

recording made in the

Hamburg Musikhalle with

Günter Wand conducting the

North German Radio Symphony

Orchestra.

The Eighth is the

last symphony for which

Bruckner wrote a complete

last movement, and at the

same time it is also the non

plus ultra of his

oeuvre, as far as both

dimensions and inner

complexity are concerned.

With a total length of 85

minutes, the Eighth

surpasses even the hitherto

unparalleled monumental

proportions of Beethoven’s Ninth.

Bruckner adopts his great

predecessors two middle

movements, albeit in

‘reversed’ order: the

Scherzo precedes the Adagio.

Nonetheless, there are

differences and contrasts

aplenty between the

culmination of Bruckner’s

symphonic oeuvre and that of

Beethoven's, whom he so

revered. In terms of

instrumentation alone, one

cannot help but be impressed

by the huge body of wind and

percussion that the work is

scored for: triple woodwind

including double bassoon, 8

horns (4 of them alternating

with tubas), triple brass

plus double bass tuba, 3

harps, 6 timpani, cymbals

and triangle - all this

naturally calls for

reinforcement of the

strings, too. The block-like

musical structures and

forms, the instrumentation

along the lines of organ

registers, the `chorales`

for the wind section, the

thematic cross-links between

the movements and in

particular the resumé in a

finale that towers above the

rest of the piece: these are

all distinctive elements of

Bruckner’s personal style.

We are familiar with them

from the earlier symphonies,

but in the Eighth

they appear developed to a

unique and consummate

intensity: the result is a

monumental design quite

without parallel.

The first movement has three

thematic groups that are

developed, continued and

expanded one after another

in the exposition, and are

then joined together in the

development section. The

rhythmically accentuated

main subject, melodically

characterised by chromatic

steps of a second, begins in

the low strings to the

tremolo of the violins,

which are supported by two

horns. The music picks up

and intensifies rapidly,

forming duplets and triplets

- first side by side, but

soon overlapping as well, in

typical Bruckner manner. The

second subject is built up

with ‘terraced`

instrumentation: the strings

enter first, then the

woodwind, then the brass. In

the closing group, the music

is dominated by three

thematically important jumps

of a seventh. The

development brings

inversions, magnifications

and contrapuntal

combinations that lead up to

the climax. Bruckner takes

us cautiously into the

reprise with completely new

instrumentation, and without

any obvious signposting of

the road ahead. In the coda,

the main subject is divided

into its rhythmic and

songful elements. The

inexorably pounding,

double-dotted rhythms lead

up to the last climax in

triple fortissimo, (fff).

Bruckner called this

powerful passage before the

dynamics abruptly fall off

again “proclamation of

death”, while he tried to

characterise the last

thirteen bars in extreme

pianissimo with the title

“clock of death”: an

ostinato violin figure with

a monotonous rhythm is

combined with a brief

drum-roll, repeated in each

bar. In terms of

tone-painting, this can be

interpreted as a

perpendicular movement and a

clockwork gradually running

down; in terms of the

compositional structure,

though, it is strictly

derived from the movement’s

opening theme. It is

interesting to note that

this is the only first

movement of a Bruckner

symphony that has a

‘falling’ ending like this,

bringing the movement to a

tranquil and silent end.

Clearly, this could not be

followed by a quiet Adagio.

The Scherzo that Bruckner

thus placed second begins

with a powerful and

energetic first subject,

whose impetuous urgency the

composer tried to describe

with the rather

inappropriate title of “Der

deutsche Michel”, which

translates as "the plain,

honest German". In the A

flat trio in 2/4 time, the

music has a certain

traditional Austrian

character, with soft horn

sounds and dreamy harp

arpeggios evoking occasional

reminiscences of Schubert.

But thematically and

structurally speaking, this

movement likewise evolves

out of the basic material of

the first movement. The

entire vast edifice of a

symphonic cosmos emerges

from the tension between a

handful of notes and metric

elements, producing in turn

one new constellation and

one new insight after

another. With the exception

of the Fifth Symphony,

Bruckner never achieved such

logical coherence of the

elements as he does here,

where the inner force of the

substances clears its own

way through all the

movements to the imposing

finale.

The form and the

transcendental mood of the

Adagio recall the example of

Beethoven’s prodigious Ninth

Symphony, a model that

was never far from

Bruckner's eyes, but which

he never tries to actually

imitate, neither here nor in

the other movements.

Bruckner is an adagio

composer sui generis,

and here he paints a

profound picture of his

innermost feelings; for all

the individuality of this

music, the composer never

loses sight of the material

of the first movement, which

again provides the basic

ingredients from which the

entirety of the Adagio is

developed. The foundation is

given by the characteristic

alternation between duplets

and triplets, disguised here

by ligatures. Chorale chords

on the strings are

embellished by rippling harp

sounds. As far as the

orchestration is concerned,

the usual body of

instruments is supplemented

in this movement by a solo

violin, the soft Wagner

tubas and at the final

climax, before the movement

dies away quietly in a

manner reminiscent of the

end of the first movement,

by the cymbals and triangle.

The last movement of the Eighth

Symphony is the last

finale that Bruckner

completed, and represents a

fitting culmination to both

this monumental symphony and

perhaps to his entire

oeuvre. Bruckner’s ability

to compose yet another

exceptionally complex

metamorphosis from the basic

substance of the three

preceding movements,

bringing it to a final

climax where all the main

themes come together at

last, is nothing short of

alarming. It's hard to say

whether Bruckner’s own

slightly naive description

as “Meeting of the three

emperors” refers to this, or

solely to the vital and

resplendent element of the

opening. Either way, this

becomes irrelevant in the

face of the almost infinite

wealth of structural links,

cross-references and

derivations of this

magnificent last movement,

which sums up all that has

gone before and finally

leads into the simultaneous

presentation of all the main

subjects, superimposed one

upon the other in masterly

contrapuntal stretto. The

music scholar U. Schreiber

describes this majestic song

of triumph in radiant C

major thus: "Struggle and

despair, victory and

resignation are united in a

unique apotheosis, and

reconcile God with the world

and art with life for the

very last time in the

history of the symphony".

Wolfgang

Seifert

(English

translation: Clive

Williams, Hamburg)

|

|

|