|

|

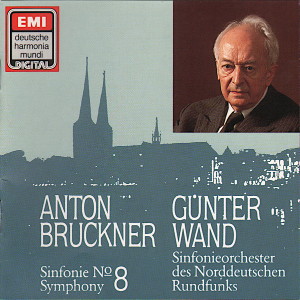

2 CD's

- CDS 7 49718 2 - (p) 1987

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 8 in C minor

- 1884-90 Originalfassung

herausgegeben von Robert Haas |

|

86' 11" |

|

-

1. Allegro moderato

|

16' 50" |

|

CD 1 |

| -

2. Scherzo. Allegro moderato |

15' 37" |

|

CD 1 |

| -

3. Adagio. Feierlich langsam; doch

nicht schleppend |

28' 29" |

|

CD 2 |

| -

4. Finale. Feierlich, nicht schnell |

25' 15" |

|

CD 2 |

|

|

|

|

| Sinfonieorchester

des Norddeutschen Rundfunks Hamburg |

|

| Günter WAND |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Lübecker

Dom, Lübeck (Germania) - 22 &

23 agosto 1987

|

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Producer |

|

Gerhard

Arnoldi |

|

|

Recording Engineer |

|

Friedrich-Karl

Wagner, Karl-Otto Bremer |

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

Nessuna

|

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

DEUTSCHE

HARMONIA MUNDI - CDS 7 4917 2 - (2

CD's - 32' 27" & 53' 44") -

(p) 1987 - DDD

|

|

|

Note |

|

The

final two concerts of the 1987

Schleswig Holstein Music Festival

were performance of Anton

Bruckner's Symphony No. 8 on 22nd

and 23rd August in Lübeck

Cathedral. The concentrated

attention of the capacity audience

in the cathedral was such that

this recording of those

performances is almost free from

any extraneous noises.

Eine Co-Produktion mit dem NDR

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anton

Bruckner: Symphony No. 8

in C minor (1884-1890)

First performance:

18th December 1892

In

September 1887 Anton

Bruckner sent the score of

his newly completed 8th

symphony to Hermann Levi,

who had conducted the Munich

premiere of his 7th Symphony

on 10th March 1885. Levi

turned the work down and the

result had a shattering

effect. Gone was the

enthusiasm (encouraged and

inspired by the success of

the 7th Symphony) with which

Anton Bruckner had conjured

up his latest work, and his

utter dejection was overcome

only very gradually - it

would be two and a half

years before yje 8th

Symphony would take its

final form. Bruckner made

such fundamental revisions -

to the first movement in

particular - that it is a

wonder that he was able to

summon up the creative

energy to do this: it is

almost inconceivable how he

managed to rework the same

material for a second time

to form a completely new and

much more cohesive whole -

what self-discipline and

compositional

professionalism after such

resignation and

helplessness.

The 8th Symphony rose

transformed like a phoenix

from the ashes and the

dedicatee, Kaiser Franz

Joseph I of Austria, paid

for the work to be

published. The first

performance in the Große

Musikvereinssaal with the

Vienna Philharmonic

Orchestra under Hans Richter

was a great success.

Bruckner had won over the

public with a work that was

both outwardly and

structurally his most

complex work. With the

possible exception of his

5th Symphony, Bruckner had

never before achieved such a

synthesis of all the

elements in a work which

follow through all its

movements into the Finale.

The power of its content is

arresting from the

beginning: out of nothing we

hear the first and third

horns in octaves with the

violins; immediately, under

them, the low strings begin

the powerful recurring

motive with the interval of

a minor second in the rhythm

of an upbeat semiquaver

followed by a crotchet. The

second is then expanded to a

minor sixth (up to an E

flat) which is then followed

by three falling semitones

(D - D flat - C) - the

falling motive ends the coda

of the first movement and is

also heard in the powerful

tutti of the last bar of the

Finale as its final

affirmation as the central

idea of the symphony.

Already in the first

movement there begins a

process of continuous

motivic development: the

main theme evolves gradually

and is transformed by means

of the use of contrasting

duplets and triplets against

each other (often known as

the "Bruckner Rhythm"). The

theme is repeated fortissimo

and the second subject

follows, based almost

entirely on the "Bruckner

Rhythm". Then the violins

have a "broad and

expressive" melody which is

immediately transformed in

its repetition by the wood

wind. In the recapitulation

of the second section,

Bruckner creates a new

rythmic cell in the first

oboe which only a few bars

later leads into the start

of the third theme. The

subdividing function of the

interval of a second from

the beginning of the

Symphony now becomes

apparent - firstly before

the entry of the third theme

(on the flute), and then

before the transition to the

development (oboe I, cellos

and basses). The exposition

ends with the falling

chromatic motive, a melodic

transformation of the main

theme (horn and oboe). The

above serves to give a

sufficiently detailed

description of the main idea

of the symphony. The

principle of the work is to

employ constant thematic

variation in order to

intensify the vastness of

the work's construction (and

indeed of its scale); to

operate on the almost

self-generating material

with rhythmic expansion or

contraction, melodic

development and inversion

and different contrapuntal

layers; to build a giant

construction in the

symphonic cosmos from only a

few notes and basic rhythmic

elements: this is the

principle which pervades the

work. Everything is

continually flowing - within

the context of an expanded

classical form - constantly

giving new insights and

always moving towards new

constellations. The jump of

a sixth (going both up and

down) in the first theme

leads into the Trio and the

ghostly isolated interval of

the minor second haunts the

thick texture of the wind

instruments in the Scherzo,

while the crashing timpani

motive of upbeat followed by

downbeat is also a main

feature of the Finale.

Nothing is lost in this

world picture which to a

certain degree is entropic.

The expansive Adagio has an

expanded rhythmic base which

disguises, but does not

deny, the presence of the

everchanging pattern of

duplets and triplets and

which are often tied

together. The main theme of

the movement is derived from

the minor second/minor

sixth; the written-out

double trill, which

separates the second theme

in the first movement,

returns in the first

fortissimo (and recurs in

corresponding places). The

ascending chords played by

the harp form a link back to

the Trio. And at the climax

of the Adagio, a variant of

the main theme of the

Allegro moderato is heard.

Even the pianissimo coda is

reminiscent of the close of

the first movement: in

almost the same rhythm the

tenor tubas intone the

initial interval of a minor

second.

Anton Bruckner's skill in

composing another

multi-layered metamorphosis

out of the basic material of

the first three movements,

and then finally crowning it

with the juxtaposition of

all the main themes is quite

amazing. The full complement

of wind instruments in the

first theme clearly refers

back to the opening theme of

the symphony (ie. double

dotting and the use of the

minor second and minor sixth

jumps); the second theme, on

the other hand, makes use of

the melodic lines of the

second theme of the Adagio.

Logically this allembracing

movement should ultimately

give on overall impression

of simultaneity - as a

result of the manysided

interweaving and development

of those opening intervals

over 80 minutes. The

clearcut montage of blocks

of music lends the movement

a certain transparency:

rhythmically pointed,

clearly separated sections

with their typically

Brucknerian changes of

register allow the listener

to grasp a type of sonata

form whose recapitulation

(like that of the first

movement) only becomes

recognisable with the

appearance of the second

subject. The borders are as

fluid as the stream of

transformations which begin

as early as the third bar of

the symphony. And the limit

of the classical-romantic

form is reached; a form

which still proves itself to

be valid, and which even now

is subject to permanent

variation: just as at one

time the gothic

master-builder would

construct giant arches with

apparent ease from the

colossal weight of his raw

materials, so Anton Bruckner

expanded his last completed

cyclic construction in a way

which could only be

described as architectural.

© Eckhardt

van den Hoogen, 1987

(Translation:

David Ashman)

|

|

|