|

|

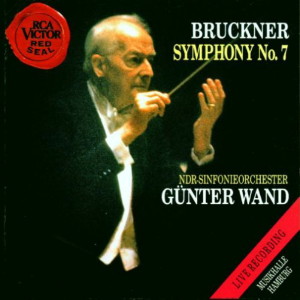

1 CD -

09026 61398 2 - (p) 1993

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 7 in E major - Originalfassung |

|

65'

05"

|

|

| -

1. Allegro moderato |

19' 28" |

|

|

-

2. Adagio; Sehr feierlich und sehr

langsam

|

21' 49" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo: Sehr schnell |

10' 00" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu

schnell |

12' 14" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NDR-Sinfonieorchester |

|

| Günter WAND |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Musikhalle,

Hamburg (Germania) - 15-17 marzo

1992 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Recording

supervisor |

|

Gerald

Götze |

|

|

Recording engineer |

|

Karl-Otto

Bremer |

|

|

Editing |

|

Suse

Wöllmer

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

SONY

[RCA VICTOR Red Seal] - 09026

61398 2 - (1 CD - 65' 05") - (p)

1993 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

A

Co-Production of Bertelsmann Music

Croup & Norddeutscher Rundfunk

Hamburg |

|

|

|

|

|

Anton

Bruckner

After

years of rejection and

neglect, the reception of

Anton Bruckner as a

symphonic composer took a

decisive turn in 1884 with

his Seventh Symphony in E.

Up to this point the

composer had faced a

veritable fortress of

stupidity, humiliation and

hostility in Vienna. He, and

especially his symphonies,

had been the favorite target

of the conservative Viennese

critical press, who saw in

him “by far the most

dangerous musical innovator

of our time” and feared

through him the “transferral

of Wagner's dramatic style

to the symphony.” It is

amazing that Bruckner

nonetheless held fast to his

convictions, and was willing

to yield to current taste

and revise his symphonies

only under the pressure of

ever-increasing resistance.

On December 30, 1884, in the

presence of the composer, a

young opera conductor named

Arthur Nikisch directed the

first performance of

Bruckners Seventh at the

Leipzig Stadttheater, before

an audience which, though

certainly conservative, was

open-minded compared with

the Viennese. Their full

quarter-hour of applause

signaled a historic moment,

which itself would be

superseded a few weeks later

at a second performance. The

unanimous enthusiasm for

Hermann Levi's

interpretation at the Munich

Odeon on March 10, 1885,

culminated in the statement

of the South German

Press and Munich

News that the

composition “could only be

compared to Beethoven's most

magnificent works.” This was

a break-through for the

60-year-old Anton Bruckner;

his hour had indeed arrived.

But not wholly: the time was

not yet ripe for an

unprejudiced reception of

Bruckner which might be

directed exclusively toward

the original versions of his

symphonies; even today that

is fairly remote. But since

Bruckner produced only one

authoritative version of his

Seventh Symphony (composed

between September 1881 and

September 1883), the problem

should not arise here - yet

it does. The autograph

actually reveals that

Bruckner made a number of

revisions after the first

performance, among them the

insertion of a controversial

cymbalcrash at the climax of

the the slow movement (at

rehearsal-letter W),

which had not originally

been in the score.

On January 10, 1885,

Bruckner's pupil Josef

Schalk wrote to his brother

Franz: “Perhaps you have not

heard that Nikisch has put

through the cymbal-crash we

wanted so much in the Adagio

(on the C-major six-four

chord), along with the

triangle and timpani, which

makes us tremendously

happy.” Bruckner gave in to

the pleas of the young

kapellmeister Nikisch and

glued a strip into the right

margin of the autograph

score, with the added parts

for timpani, triangle and

cymbals, but at the same

time he put six

question-marks undemeath,

expressing his doubts. Some

time later, he crossed out

the question-marks with a

heavy stroke and wrote above

the whole addition, “No

good.”

Common performance practice

unfortunately still ignores

Bruckner's retraction, and

understandably prefers the

spectacular cymbal-crash.

Two further inconsistencies

are usually overlooked as

well. In the first instance,

the added timpani part as

notated one bar after W

does not go with the

orchestral bass part on the

tonic C, but persists for an

extra bar on the dominant G.

It seems the timpani comes a

bar too late, although, to

be sure, the “suspension” is

not heard as a dissonance.

In the second instance, the

Seventh Symphony is the only

one of Bruckner's nine in

which the original version

of the slow movement has no

parts for timpani, cymbals

or triangle. The conductor

therefore has every reason

to take the composers

original version seriously,

and to ignore the additions

on musical and aesthetic

grounds.

Moreover, Bruckner's Seventh

does not need these effects

for its success, which is

due rather to the power of

its ideas and the

intelligibility of their

development, to the relative

simplicity and

understandability of its

architecture, ultimately to

the inimitable glow of the

score. It is entirely

dependent upon the harmony

and color that come from

Bruckner's own blending of

organlike instrumentation

with the brilliance of a

kaleidoscopic orchestration.

The use of four tubas is

only one of the evidences of

Richard Wagner's influence.

This tuba quartet casts its

color over the second

movement in particular,

which Bruckner intended as

an epitaph for Wagner. (In

fact, the news of Wagner's

death reached Bruckner when

he was starting to write the

coda: “and then I began to

write the real funeral music

for the Master.”) It is an

Adagio full of dignity and

grandeur, whose climax

(letter W) is the

culmination of the entire

symphony, from which point

everything generally slopes

away, notwithstanding later

ascents. Preceding it is a

sonata-allegro of three

themes, whose development

serves only as a preparation

or introduction to the slow

movement, and which

contrasts as much to it in

meaning and intensity as

does the Scherzo that

follows.

Like the introductory

Allegro and the Finale, this

Scherzo in three-part song

fomr is built upon the pure

natural intervals of the

fourth and fifth, which

usually suggest

nature-idylls or Austrian

folklore.

But instead this Scherzo

whirls demonically, catching

its breath only in a softly

luminous Trio. “With motion,

but not fast,” the Finale

recalls the beginning of the

symphony with a variant of

the first theme of the first

movement. But now Bruckner

transforms its hesitant

restraint into energetic,

high-strung activity, until

he actually refers back to

the symphony's beginning in

the coda (an original

structure combining elements

of rondo and sonata form),

blending that theme with the

closing material. It would

be hard to imagine an inner

logic and unity more

effective than the symphonic

events bracketed between

these two ideas.

Ekkehart

Kroher

(Translation: Lucy

Cross; Byword, London)

|

|

|