|

|

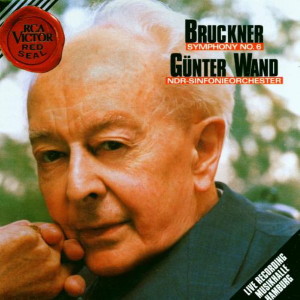

1 CD -

09026 68452 2 - (p) 1996

|

|

| ANTON BRUCKNER

(1824-1896) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Symphony

No. 6 in A major - Originalfassung

1879-1881 |

|

55'

07"

|

|

| -

1. Maestoso |

16' 37" |

|

|

| -

2. Adagio. Sehr feierlich |

15' 57" |

|

|

| -

3. Scherzo. Nicht schnell - Trio.

Langsam |

8' 50" |

|

|

| -

4. Finale. Bewegt, doch nicht zu

schnell |

13' 41" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NDR-Sinfonieorchester |

|

| Günter WAND |

|

|

|

|

|

Luogo

e data di registrazione |

|

Musikhalle,

Hamburg (Germania) - 15 maggio

1995 |

|

|

Registrazione:

live / studio |

|

live

recording

|

|

|

Recording

supervisor |

|

Gerald

Götze |

|

|

Balance engineer |

|

Johannes

Kutzner |

|

|

Technik/Engineering |

|

Andreas

Schulz |

|

|

Editing |

|

Suse

Wöllmer

|

|

|

Prima Edizione LP |

|

nessuna |

|

|

Edizione CD |

|

SONY

[RCA VICTOR Red Seal] - 09026

68452 2 - (1 CD - 55' 07") - (p)

1996 - DDD |

|

|

Note |

|

A

Co-Production of Bertelsmann Music

Croup & Norddeutscher Rundfunk

Hamburg |

|

|

|

|

|

Symphony

no. 6 in A major (original

version)

Bruckner’s

originality and modernity

could not be fully

appreciated during his

lifetime, even by his

pupils, friends and musical

colleagues, let alone by the

uncomprehending world at

large. The composer, plagued

all his life by feelings of

inadequacy, was constantly

under pressure from

well-meaning people to

rearrange and shorten his

works and even to agree to

the deletions and

reinstrumentations they

proposed. Although intended

to promote

comprehensibility, such

“improvements” actually

falsified and distorted the

original architecture,

dynamics and sound

structure. Nevertheless in

the innermost core of his

artistic self Bruckner was

not to be diverted. By and

large, having once declared

a version of a work to be

"valid" he adhered to that

version, ensuring that it

would be handed down to

posterity through

unequivocal instructions in

his will. Based upon these

autographed original scores

in the music department of

the former Library of the

Imperial Court, now the

Vienna National Library,

Robert Haas was able,

between 1932 and 1944, to

publish the first complete

edition of Bruckner`s works

purged of all extraneous

influences. Only then was it

possible to perceive the

full extent to which the

idiosyncratic terraced

dynamics and register-like

orchestration - originating

essentially in organ

technique - characterize

Bruckner`s symphonic

writing, obeying laws and

tonal conceptions which,

despite contemporaneity and

personal admiration, diverge

in kind from the seductively

magical constant state of

flux exhibited in Wagner’s

tonal palette.

Notwithstanding parallels in

harmonic structure, Bruckner

chose a direction quite

distinct from that of the

Bayreuth wizard - a fact

that his contemporaries,

firmly convinced of his

being a Wagnerian, simply

could not see. Even a man so

musically well-versed as

Eduard Hanslick heard only

the similarities, not the

enormous differences. For

this reason he attacked

Bruckner as a neo-German

revolutionary in polemical

reviews in which he played

him off against Brahms, the

upholder of tradition.

Bruckner, however, having

once chosen a course of

action, unerringly pursued

it to the bitter end

regardless of the

consequences. From 1875

onwards he was to devote

almost as much time to

arranging second and third

versions as he did to

creating new works. When he

died he had heard

practically none of

his symphonies in the form

in which he had composed

them: he never heard his

Fifth and Sixth Symphonies

or the three completed

movements of the “Ninth” in

any form at all.

Bruckner had little to do

with fashionable trends and

disputing factions. At peace

in his deep devoutness, he

wrote all his music - not

only those pieces expressly

dedicated to “the blessed

Lord” as the medieval

masters and even Johann

Sebastian Bach had done,

“soli Deo gloria”: solely in

honour and praise of God. In

the monumental edifices of

his overarching symphonic

architecture he repeatedly

attempted to embrace the

totality of the formal and

expressive means available

to orchestral composition in

his time, intensified and

enhanced to the ultimate

attainable degree of

magnitude and sublimity.

Each of his symphonic works

thus reflects one and the

same idea.

In consequence, Bruckner’s

symphonic oeuvre represents

the culmination of an entire

epoch in the history of

western music in which the

purpose and raison

d’être of music was

seen as deriving from its

transcendence, its ability

to reflect ethical content

in aesthetic terms. For

philosopher Ernst Bloch,“the

music concerned seems indeed

to be part of a mathematical

system in the hands of the

Almighty.”

Bruckner began his Symphony

no 6 in A major in

August/ September 1879.

Completed two years later,

the composition was

dedicated to Dr and Mrs

Anton von Oelzelt-Nevin,

Bruckner`s landlord and his

wife. Unsatisfactory though

the performance may have

been, Bruckner did at least

live to hear a rehearsal of

the entire symphony. In the

concert given on February

11, 1883 however, the Vienna

Philharmonic performed only

the second and third

movements, conductor Wilhelm

Jahn considering the outer

movements impossible. The

first complete performance -

albeit in an abridged and

somewhat reinstrumented

version - was conducted by

the young Gustav Mahler in

1899. In unabridged form,

the work was first heard in

Stuttgart in 1901 under the

baton of Wilhelm Pohlig. The

score published in the same

year contained many

alterations not stemming

from Bruckner. Only in 1934,

in the course of Robert

Haas’s work on his complete

critical edition of

Bruckner’s works, were all

extraneous additions

removed. Paul von Kempen

conducted the first

performance of the original

version in Dresden in 1935 -

more than 50 years after the

work was completed.

··········

Bruckner’s

Sixth Symphony is less

frequently performed than

his other orchestral works

for reasons which can hardly

be explained in rational

terms. Both the records

concerning its conception

and the source documents are

unambiguous in pointing to

there being only one

,,valid“ version, and the

work is neither longer nor

structurally more

complicated than, for

instance, the “Fifth” and is

no more difficult to

perform. On the contrary,

its duration is far shorter

than that of the “Fourth” or

“Seventh” which have become

much more popular, and the

forces it calls for -

doubled woodwinds, four

horns and three trumpets and

trombones plus a tuba - are

in fact modest by

comparison.

The A major Symphony is the

first of the great symphonic

works of Bruckner’s late

period. Perhaps the reason

why this symphony gives a

lighter and brighter

impression than its

predecessor lies in the

composer’s successes as an

organist during his 1880

tour of Switzerland and in

his having been able to

experience the première of

his “Fourth” in Vienna in

1891 conducted by Hans

Richter.

Nevertheless, the structural

achievements of its

predecessor form the

foundation upon which this

symphony now builds. Whereas

the “Fifth” represents an

almost violent eruption of

radical symphonic genius,

the "Sixth" while reflecting

perhaps upon natural

grandeur experienced high in

the Alps, represents

anything but a stylistic

retreat on Bruckner’s part,

and certainly does not

depict his dream of “happy

country life.” In the formal

structure of this symphony

he attains a new degree of

concentration, eschewing all

long-windedness and, in the

outer movements and the

Adagio, adhering to

tripartite thematic

architecture. “One cannot

but admire” comments R.

Kloiber, “the logic employed

in the development of the

themes, which, despite their

differences, exhibit

relationships to each

other.”

The first movement

is one of the most

organically conceived and

formally transparent

movements Bruckner ever

wrote, being, despite its

intricate contrapuntal

combinations, festive rather

than dramatic and aggressive

in character. The

transcendental character of

the second movement

counterpoises the worldly

vitality of the first; a

relatively short, profound

and “very solemn”Adagio is

presented in undeveloped

sonata form with

sophisticated variations.

The third movement

is of quite special

character. Here, Bruckner

introduces a completely new

type of scherzo into his

symphonic repertoire - a

scherzo no longer derived

from the rustical,

ländler-like folk dance.

“Demonic and spooky” is

Kloiber’s term for the

movement, while Kurt

Blaukopf and Wulf Konold

quite rightly detect in it

“virtually impressionistic

traits.” In the Trio,

alternating between

pizzicato violins and the

horns, a short motif is to

be heard that quite

unexpectedly echoes the main

theme in the first movement

of the Fifth Symphony - an

ingeniously incorporated

quotation from his own work,

with which Bruckner again

provides evidence of his

creative use of established

forms.

The thematic material of the

final movement,

largely derived from the

themes in the first

movement, is so simple in

its architecture that

Bruckner might well have

intended it to set an

example of the ultimate in

formal coherence. Naturally,

it again incorporates the

sonata-form principle, with

its three main themes,

development, recapitulation

and finally a coda ending in

the triumphant radiance of

the combined main themes of

both the first and last

movements.

The interrelation of almost

all the themes in this

symphony and their ingenious

interweaving by means of

motivic combination result

in a cohesion between

movements ensuring the

intellectual coherence of

the work, impressively

marking a new highpoint in

Bruckner’s mastery over his

medium.

Wolfgang

Seifert

(Translation: Janet

& Michael Berridge)

|

|

|